This tough and unflinching Tyneside police thriller is the latest outing for Mari Hannah’s DCI Kate Daniels. The Longest Goodbye is the ninth in a series which began in 2012 with The Murder Wall. We are in late December 2022, and in Newcastle, like other cities across Britain, revellers are raising two fingers to the recently discovered Omicron variant of the Coronavirus, and are out in the clubs and pubs wearing – because it is Newcastle, after all – as little as possible, despite the freezing weather. Two lads in particular – homeward bound from overseas, and just off the plane – are determined to have a few beers before being reunited with mum and dad.

However, neither the two bonny lads nor mum and dad quite fit the ‘home for Christmas’ template. Lee and Jackson Bradshaw are only in their twenties, but have already done serious time for violence, and are returning from a European bolthole where they have been hiding from British police. Mum and Dad? Don Bradshaw is a career criminal, but pales into insignificance beside his wife Christine, who is the ruthless boss of the region’s biggest crime syndicate.

When the two prodigal sons are gunned down on the doorstep of their parents’ (recently rented) home just as they are about to sing ‘Silent Night‘, la merde frappe le ventilateur (pardon my French) The police are called and Don Bradshaw, brandishing the handgun dropped by one of his sons, is shot dead by a police marksman. No-one on the staff of Northumbria police will mourn three dead Bradshaws, but for Kate Daniels, the incident opens up a particularly unpleasant can of worms. Three years earlier, her best friend and police colleague Georgina Ioannou was found dead in a patch of woodland. Shot in the back. Executed. And it was the Bradshaw boys who were prime suspects.

Kate is forced to think the unthinkable: that Georgina’s twins, Oscar and Charlotte, now both police officers, were involved; even worse is the thought that Georgina’s husband Nico, although ostensibly a peaceful restaurateur, has avenged his wife’s murder. Revisiting old cases is never easy, and this one is made even worse by the fact that the Senior Investigating Officer at the time, was lazy, incompetent, and all-too-willing to cut corners.

Mari Hannah does not spare our sensibilities. She takes us through the painful process of self-examination one uncomfortable step at a time. It isn’t just Kate Daniels who must own up to past mistakes and errors of judgment, it is the whole Major Incident Team. Meanwhile, although the appalling Christine Bradshaw is safely behind bars facing a murder charge (the Firearms Officer she brained with a baseball bat has since died) like a badly treated tumour, malignant cells remain, and these men, enabled by her corrupt lawyer, are hard at work on the streets and in the pubs, clubs and private homes of Newcastle, determined to prevent the police from discovering the truth.

The Longest Goodbye, with its gentle nod to the Raymond Chandler thriller of almost the same name, grips from the first page, and we are fed the reddest of red herrings, one after the other, until Mari Hannah reveals a murderer who I certainly had not suspected. While few mourn the two dead criminals, when their killer is finally unmasked it is heartbreaking on so many levels. This is superior stuff from one of our finest writers. The Longest Goodbye is published by Orion and was published on 18th January.

In 1968 Hamish Hamilton (by then part of the Thomson Organisation and subsequently to be bought by Penguin) published The Burden Of Proof, a novel by the Birmingham born author James Barlow. The firm had something of a hit seven years earlier with Barlow’s Term of Trial. That novel, about a teacher accused of indecency with a pupil, was made into a successful film starring Laurence Olivier, Simone Signoret, Sarah Miles and Terence Stamp. The Burden Of Proof was a different beast altogether, but first a little bit of history.

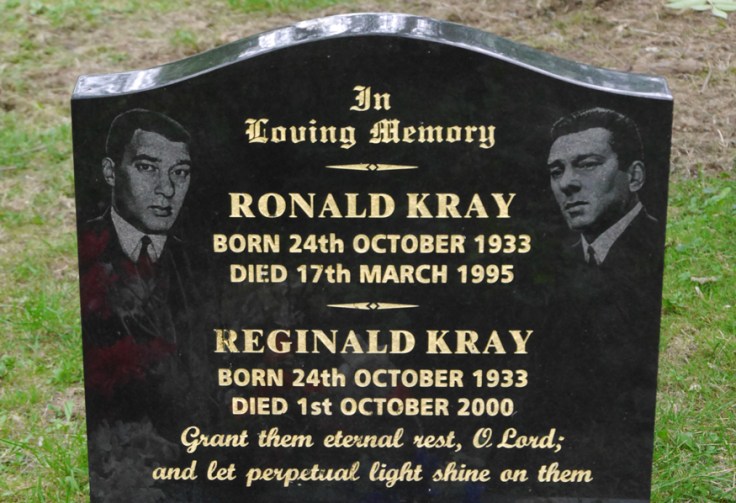

In 1968 Hamish Hamilton (by then part of the Thomson Organisation and subsequently to be bought by Penguin) published The Burden Of Proof, a novel by the Birmingham born author James Barlow. The firm had something of a hit seven years earlier with Barlow’s Term of Trial. That novel, about a teacher accused of indecency with a pupil, was made into a successful film starring Laurence Olivier, Simone Signoret, Sarah Miles and Terence Stamp. The Burden Of Proof was a different beast altogether, but first a little bit of history. n 8th May 1968, led by Detective Chief Superintendent Leonard ‘Nipper’ Read, the Metropolitan Police arrested Reg and Ron Kray, along with sundry members of their gang. Neither of the Kray twins was ever to see freedom again, apart from when Reg spent his final hours dying from cancer in the honeymoon suite at the Beefeater Town House Hotel in Norwich. In 1968, the particular character of Ron Kray was not widely known to the general public, as the whole Kray ‘industry’ of ghosted memoirs and personal accounts of ‘The Twins I Knew’ by minor London villains had yet to take wing. Ron Kray was a homosexual psychopath, and it’s as simple as that. Whether brother Reg was any better for being heterosexual is neither here nor there, but Ron’s peccadillos were mirrored in dramatic fashion in The Burden Of Proof.

n 8th May 1968, led by Detective Chief Superintendent Leonard ‘Nipper’ Read, the Metropolitan Police arrested Reg and Ron Kray, along with sundry members of their gang. Neither of the Kray twins was ever to see freedom again, apart from when Reg spent his final hours dying from cancer in the honeymoon suite at the Beefeater Town House Hotel in Norwich. In 1968, the particular character of Ron Kray was not widely known to the general public, as the whole Kray ‘industry’ of ghosted memoirs and personal accounts of ‘The Twins I Knew’ by minor London villains had yet to take wing. Ron Kray was a homosexual psychopath, and it’s as simple as that. Whether brother Reg was any better for being heterosexual is neither here nor there, but Ron’s peccadillos were mirrored in dramatic fashion in The Burden Of Proof. Vic Dakin is a London gangster who has political connections, and has yet to have his collar properly felt, despite a string of serious crimes. He also enjoys a spot of sexual sadism, usually with his unofficial boyfriend, Wolfie, who accepts the beatings as a fact of life. Oh yes, and before I forget, Vic loves his dear old mum (who is blissfully unaware of Vic’s career choices) In the novel, Vic plans a daring wages raid on a suburban factory, in between doing all kinds of other unpleasant things to people he both likes and dislikes. Before we turn to the movie version of the book, check out my review of

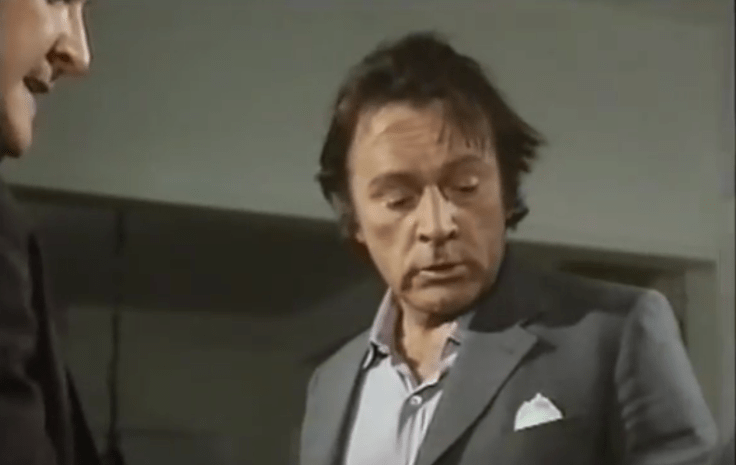

Vic Dakin is a London gangster who has political connections, and has yet to have his collar properly felt, despite a string of serious crimes. He also enjoys a spot of sexual sadism, usually with his unofficial boyfriend, Wolfie, who accepts the beatings as a fact of life. Oh yes, and before I forget, Vic loves his dear old mum (who is blissfully unaware of Vic’s career choices) In the novel, Vic plans a daring wages raid on a suburban factory, in between doing all kinds of other unpleasant things to people he both likes and dislikes. Before we turn to the movie version of the book, check out my review of  he film was released in 1971, renamed Villain. The key issue, of course, was that of who would play Dakin? The choice – Richard Burton – was a surprise at the time, and the actor later wrote that he was drawn to the role because it represented a change from his usual heroic fare. Younger folk reading this will not know what a huge star Burton was at the time. For a modern comparison you need to think Hanks, Clooney, Cruise, Fiennes or Craig. Film and TV historians will be surprised to know that the screenplay for Villain was written by none other than Dick Clement and Ian La Frenais. The duo’s lightness of touch and feeling for the vernacular of British comedy created pure gold in later works such as Whatever Happened To The Likely Lads?, Porridge, Auf Wiedersehen, Pet and Lovejoy. Maybe all that shows is that good writers are good writers, end of.

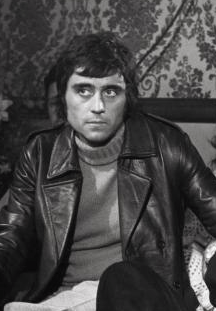

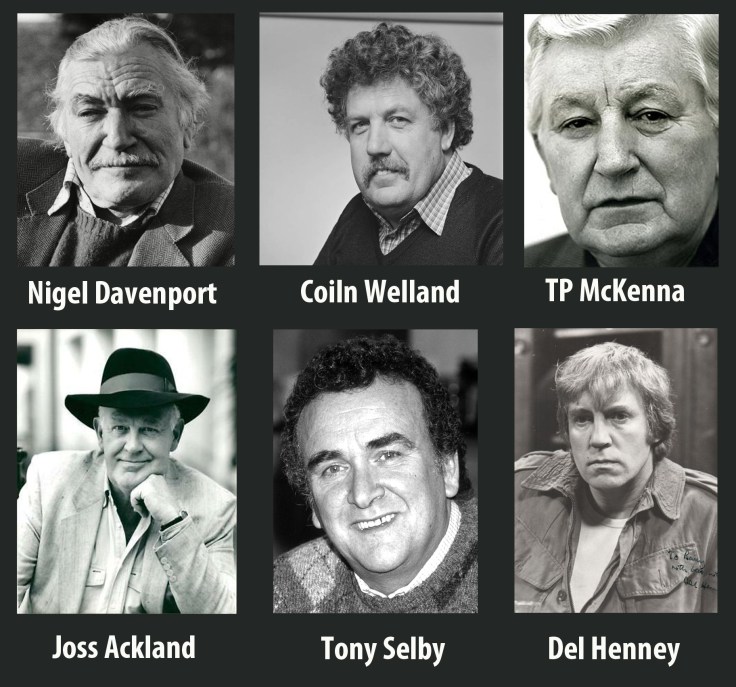

he film was released in 1971, renamed Villain. The key issue, of course, was that of who would play Dakin? The choice – Richard Burton – was a surprise at the time, and the actor later wrote that he was drawn to the role because it represented a change from his usual heroic fare. Younger folk reading this will not know what a huge star Burton was at the time. For a modern comparison you need to think Hanks, Clooney, Cruise, Fiennes or Craig. Film and TV historians will be surprised to know that the screenplay for Villain was written by none other than Dick Clement and Ian La Frenais. The duo’s lightness of touch and feeling for the vernacular of British comedy created pure gold in later works such as Whatever Happened To The Likely Lads?, Porridge, Auf Wiedersehen, Pet and Lovejoy. Maybe all that shows is that good writers are good writers, end of. With a link worthy of BBC Radio 4, I can reveal that the role of Vic Dakin’s much-abused boyfriend in Villain was played by none other than the excellent Ian McShane (right), whose many credits include the long running Sunday night TV show, Lovejoy. Back to the film, directed by Michael Tuchner (Fear Is The Key, Mister Quilp). The supporting cast was stellar. The two coppers pursuing Dakin were the much-missed. moustache-twirling Nigel Davenport and Colin Welland. The villains were equally stalwarts of the day; TP McKenna as Frank Fletcher and Joss Ackland as Edgar Lowis, not to mention Donald Sinden as the compromised politician, and regular ‘baddies’ such as Tony Selby and Del Henney (composite below)

With a link worthy of BBC Radio 4, I can reveal that the role of Vic Dakin’s much-abused boyfriend in Villain was played by none other than the excellent Ian McShane (right), whose many credits include the long running Sunday night TV show, Lovejoy. Back to the film, directed by Michael Tuchner (Fear Is The Key, Mister Quilp). The supporting cast was stellar. The two coppers pursuing Dakin were the much-missed. moustache-twirling Nigel Davenport and Colin Welland. The villains were equally stalwarts of the day; TP McKenna as Frank Fletcher and Joss Ackland as Edgar Lowis, not to mention Donald Sinden as the compromised politician, and regular ‘baddies’ such as Tony Selby and Del Henney (composite below)

id the film work? For me, it was something of a Curate’s Egg. Despite his passable snarling London accent, Burton never totally convinced me, even though he was never less than mesmeric when on screen. Villain will never be known as ‘the great London gangster movie’ – nothing will ever surpass The Long Good Friday – but that doesn’t make it a bad film. Donald Sinden was wonderful as the oily and glib politician, and Davenport and Welland were convincing, if hardly original, as the coppers. A final word of praise for the late, great TP McKenna. Check his filmography. He was never just the stage Irishman, but brought dignity and conviction to every role he played.

id the film work? For me, it was something of a Curate’s Egg. Despite his passable snarling London accent, Burton never totally convinced me, even though he was never less than mesmeric when on screen. Villain will never be known as ‘the great London gangster movie’ – nothing will ever surpass The Long Good Friday – but that doesn’t make it a bad film. Donald Sinden was wonderful as the oily and glib politician, and Davenport and Welland were convincing, if hardly original, as the coppers. A final word of praise for the late, great TP McKenna. Check his filmography. He was never just the stage Irishman, but brought dignity and conviction to every role he played.

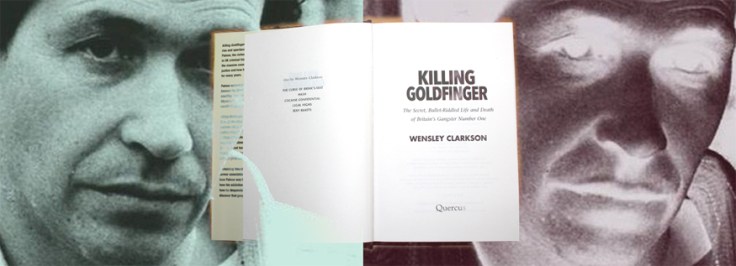

Perhaps the world has shrunk, or maybe it is that organised crime, like politics, has gone global, but more recent British mobsters have become bigger and, because we can hardly say “better”, perhaps “more formidable” might be a better choice of words. No-one typifies this new breed of gang boss than John “Goldfinger” Palmer. His name is hardly on the tip of everyone’s tongues, but as this new book from Wensley Clarkson shows, Palmer’s misdeeds were epic and definitely world class.

Perhaps the world has shrunk, or maybe it is that organised crime, like politics, has gone global, but more recent British mobsters have become bigger and, because we can hardly say “better”, perhaps “more formidable” might be a better choice of words. No-one typifies this new breed of gang boss than John “Goldfinger” Palmer. His name is hardly on the tip of everyone’s tongues, but as this new book from Wensley Clarkson shows, Palmer’s misdeeds were epic and definitely world class. Meanwhile, Palmer had not been idle, at least in the sense of criminality. He had set up in the timeshare business, perpetrating what was later proved to be a massive scam. When he was eventually brought to justice, it was alleged that he had swindled 20,000 people out of a staggering £30,000,000. In 2001 he was sentenced to eight years in jail, but his ill-gotten gains were never recovered.

Meanwhile, Palmer had not been idle, at least in the sense of criminality. He had set up in the timeshare business, perpetrating what was later proved to be a massive scam. When he was eventually brought to justice, it was alleged that he had swindled 20,000 people out of a staggering £30,000,000. In 2001 he was sentenced to eight years in jail, but his ill-gotten gains were never recovered.

March 1966. Cornell (right) was having a quiet drink in The Blind Beggar pub, well inside Kray territory on Whitechapel Road, when Ronnie walked in and put a bullet from a 9mm Luger into his head. Needless to say, none of the bar staff or other customers saw a single thing. Kray was eventually convicted of the murder when a barmaid, aware that Ronnie was already safely under lock and key for other misdeeds, testified that she had witnessed the killing.

March 1966. Cornell (right) was having a quiet drink in The Blind Beggar pub, well inside Kray territory on Whitechapel Road, when Ronnie walked in and put a bullet from a 9mm Luger into his head. Needless to say, none of the bar staff or other customers saw a single thing. Kray was eventually convicted of the murder when a barmaid, aware that Ronnie was already safely under lock and key for other misdeeds, testified that she had witnessed the killing.

REGGIE AND RONNIE KRAY have been the subject of almost as many books, documentaries and dramas as their 19th century near-neighbour Jack the Ripper. The East End that he – whoever he was – knew has changed almost beyond recognition. The Bethnal Green of the Krays is heading in the same direction, but a few landmarks remain unscathed. They were born out in Hoxton in October 1933, Reggie being the older by ten minutes. The family moved into Bethnal Green in 1938, and they lived at 178 Vallance Road. That house no longer stands, modern houses having been built on the site (left)

REGGIE AND RONNIE KRAY have been the subject of almost as many books, documentaries and dramas as their 19th century near-neighbour Jack the Ripper. The East End that he – whoever he was – knew has changed almost beyond recognition. The Bethnal Green of the Krays is heading in the same direction, but a few landmarks remain unscathed. They were born out in Hoxton in October 1933, Reggie being the older by ten minutes. The family moved into Bethnal Green in 1938, and they lived at 178 Vallance Road. That house no longer stands, modern houses having been built on the site (left)

George Cornell (right) had known the twins from childhood. Their careers had developed more or less on similar lines, except that Cornell became the enforcer for the Richardsons. On 7th March 1966 there was a confused shoot-out at a club in Catford. Members of the Kray gang and the Richardsons gang were involved. At some point, George Cornell had been heard to refer to Ronnie Kray as a “fat poof.” That might seem unkind, but was not totally inaccurate. Ronnie was certainly plumper than his lean and hungry twin, and his liking for handsome boys was well known.

George Cornell (right) had known the twins from childhood. Their careers had developed more or less on similar lines, except that Cornell became the enforcer for the Richardsons. On 7th March 1966 there was a confused shoot-out at a club in Catford. Members of the Kray gang and the Richardsons gang were involved. At some point, George Cornell had been heard to refer to Ronnie Kray as a “fat poof.” That might seem unkind, but was not totally inaccurate. Ronnie was certainly plumper than his lean and hungry twin, and his liking for handsome boys was well known. On the evening of 9th March, Cornell and an associate were unwise enough to call in for a drink at a The Blind Beggar pub on Whitechapel Road, very much in Kray territory. Some thoughtful soul telephoned Ronnie Kray, who was drinking in a nearby pub, The Lion in Tapp Street (left). Ronnie, pausing only to collect a handgun made straight for the Blind Beggar, strode in, and shot George Cornell in the head at close range. His death was almost instantaneous. Needless to say, no-one else in the pub had seen anything. Pictured below are a post mortem photograph of Cornell, and the bloodstained floor of The Blind Beggar. Below that is the fatal pub, then and now.

On the evening of 9th March, Cornell and an associate were unwise enough to call in for a drink at a The Blind Beggar pub on Whitechapel Road, very much in Kray territory. Some thoughtful soul telephoned Ronnie Kray, who was drinking in a nearby pub, The Lion in Tapp Street (left). Ronnie, pausing only to collect a handgun made straight for the Blind Beggar, strode in, and shot George Cornell in the head at close range. His death was almost instantaneous. Needless to say, no-one else in the pub had seen anything. Pictured below are a post mortem photograph of Cornell, and the bloodstained floor of The Blind Beggar. Below that is the fatal pub, then and now.

Folklore has it that now that Ronnie had ‘done the big one’, there was pressure on Reggie to match his twin’s achievement. The chance was over a year in coming. Jack McVitie (right) was a drug addicted criminal enforcer who worked, on and off, for the Krays. His nickname ‘The Hat’ was because he was embarrassed about his thinning hair, and always wore a trademark trilby. McVitie had taken £500 from the Krays to kill someone, had botched the job, but kept the money. He had also, unwisely,been heard to bad-mouth the twins.

Folklore has it that now that Ronnie had ‘done the big one’, there was pressure on Reggie to match his twin’s achievement. The chance was over a year in coming. Jack McVitie (right) was a drug addicted criminal enforcer who worked, on and off, for the Krays. His nickname ‘The Hat’ was because he was embarrassed about his thinning hair, and always wore a trademark trilby. McVitie had taken £500 from the Krays to kill someone, had botched the job, but kept the money. He had also, unwisely,been heard to bad-mouth the twins. On the night of 29th October 1967, McVitie was lured to a basement flat in Evering Road, Stoke Newington,(left) on the pretext of a party. There, he was met by Reggie Kray and other members of the firm. Kray’s attempt to shoot McVitie misfired – literally – and instead, he stabbed McVitie repeatedly with a carving knife. McVitie’s body was never found, and the stories about his eventual resting place range from his being fed to the fishes of the Sussex coast to being buried incognito in a Gravesend cemetery.

On the night of 29th October 1967, McVitie was lured to a basement flat in Evering Road, Stoke Newington,(left) on the pretext of a party. There, he was met by Reggie Kray and other members of the firm. Kray’s attempt to shoot McVitie misfired – literally – and instead, he stabbed McVitie repeatedly with a carving knife. McVitie’s body was never found, and the stories about his eventual resting place range from his being fed to the fishes of the Sussex coast to being buried incognito in a Gravesend cemetery.