“He now found a strange kind of peace when sitting alone with the dead. The dead were dependable. The dead had no pretence, no argument. If one only knew how to ask, the dead were always willing to share their dying secrets, their last link to the mortal world. They always told the truth”

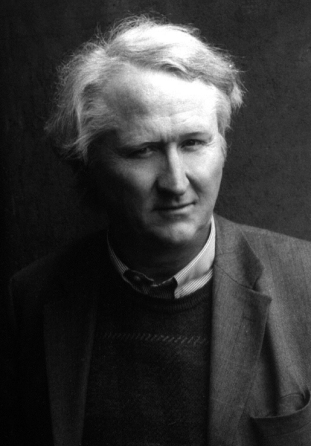

This is Duncan McCallum, a Scottish physician who has settled in Massachusetts in the febrile years leading up to the American Revolution. I read and reviewed earlier books in this series, Savage Liberty (2018) The King’s Beast (2020) – to see what I thought, just click the links.The political situation against which the events of this novel is played out are complex. The British are determined to hold on to their American colonies despite resistance from a disparate alliance of groups, including the French, native American tribes and – most significantly – the fledgling revolutionary movement – The Sons of Liberty – whose leading lights are Benjamin Franklin and Samuel Adams.

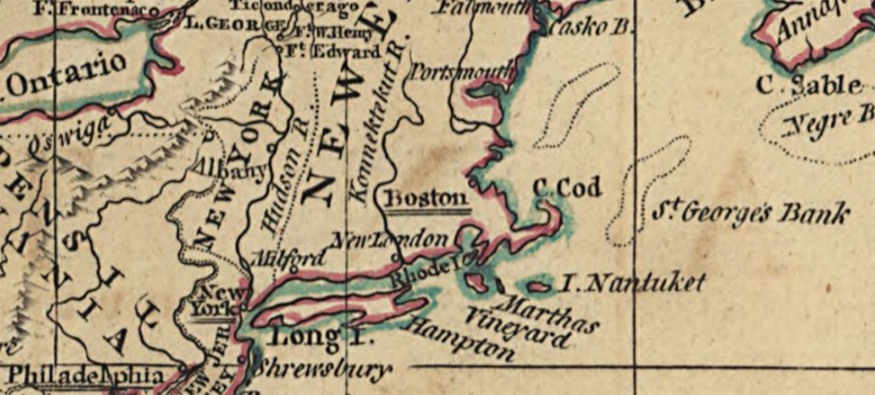

King George’s grip on his American colonies is, however, tight and wide ranging. Not only do Redcoat platoons patrol the streets of Boston and the port of Marblehead – where this novel begins – but it is illegal to import sugar and other staples from anywhere but a British colony, and the import of industrial machinery – such as the Hargreaves Spinning Jenny – is strictly prohibited. McCallum, however, is no firebrand. He, unlike his lover Sarah Ramsey, seeks a bloodless and civilised transfer of power from Britain to America. His worst nightmare is a violent uprising resulting in a bloody conflict with the professional British army.

McCallum’s work is cut out when, within the space of a few days, two British army officers are murdered. One is found crucified in a shipping warehouse, his eyelids sewn open and his mouth sewn shut. Another soldier is hauled up in a fishing net and readily identifiable despite the work of crabs and other marine predators. McCallum realises that the British army – in the shape of the 29th Regiment of Foot – now believes it has more than enough reasons to turn Marblehead upside down their search for vengeance. His problems become worse when he discovers that Sarah is hiding group of escaped slaves from Barbados, and is hoping to smuggle them away to her property up on the Canadian border.

When the warehouse of a merchant called Bradford – a man fully in sympathy with The Sons of Liberty – is burnt to the ground, with him still inside it, tortured and tied to a stake, McCallum vows vengeance. But who are the culprits? British military, for sure, but acting on whose orders? Are they renegades? McCallum’s relationship with the occupying force is ambiguous; he is made welcome in the forts and barracks because of his medical skills, but can he be trusted? He is suspicious when Sarah receives an invitation to visit New York to meet none other than the Commander in Chief of all British forces in America, General Thomas Gage. Ostensibly, he wants to use Sarah’s rapport with the warlike Iroquois-speaking tribes on the border to foster better relations with the British, and McCallum senses something more sinister when Sarah goes missing.

When McCallum eventually arrives in New York, he finds Sarah safe and well, and he meets General Gage. finding that his medical reputation has gone before him, as the General asks him to do a thorough health and hygiene inspection of the main fort. This suits McCallum very well, as he is by now engaged in an audacious plan to switch a shipload of faulty gunpowder – the Americans are unable to manufacture ‘King George’s Powder’ due to a shortage of essential ingredients – with top grade British propellant.

Eliot Pattison has produced an intoxicating blend of real events – such as the killing of Crispus Attucks – with all the imagination demanded of a modern political thriller. Freedom’s Ghost will be published by Counterpoint on 24th October

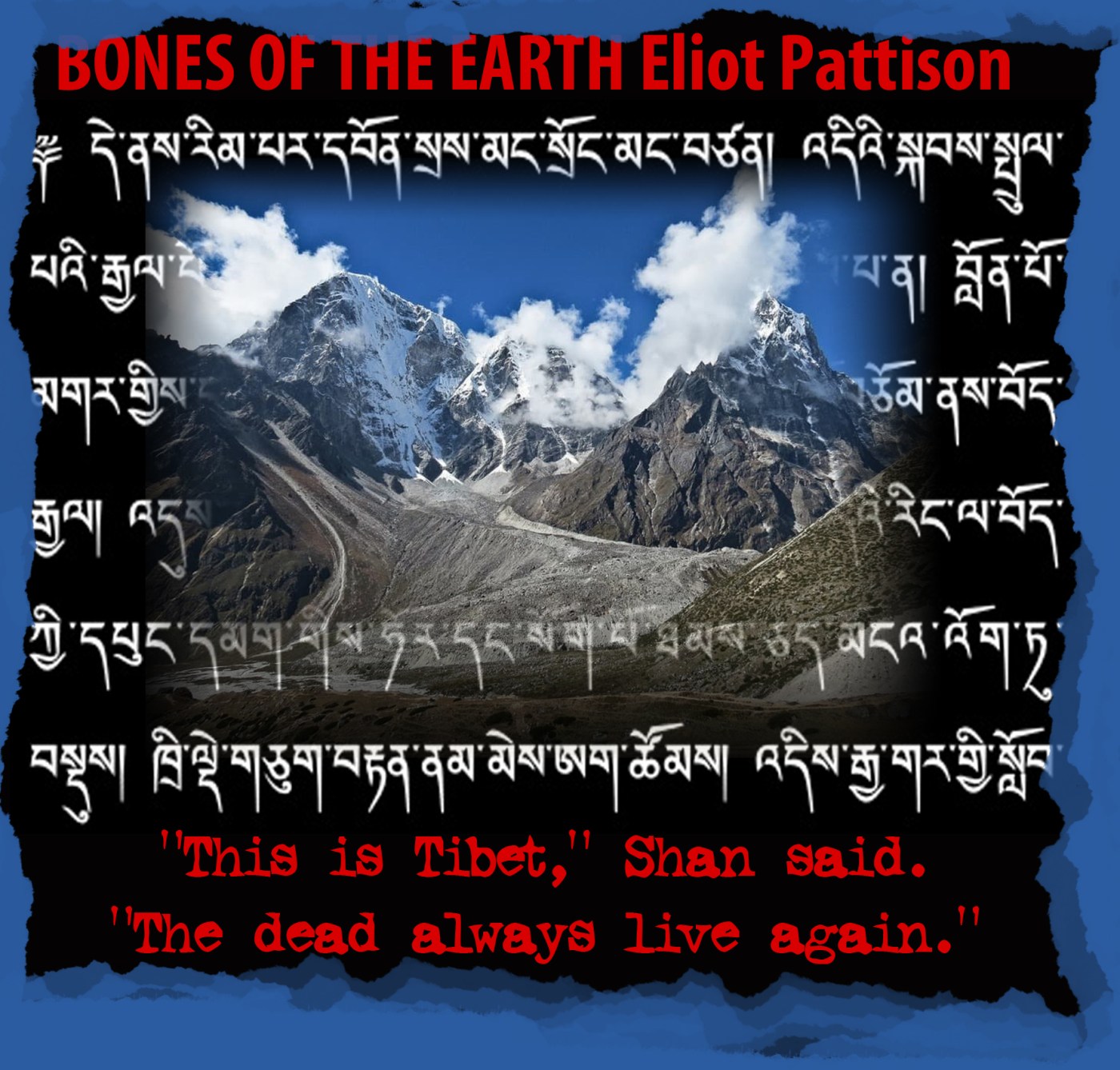

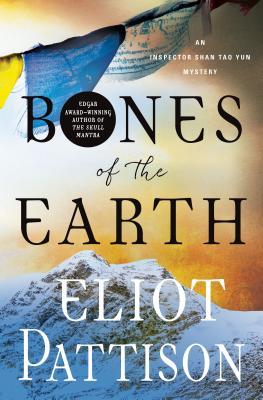

In Bones Of The Earth (the tenth and final book in the series) Shan becomes involved in a complex murder mystery involving a massive civil engineering project and a dead American.archaeology student, whose father has come to Tibet to investigate if his daughter’s death was, as the authorities declare, an unfortunate accident or something more sinister. As ever in the series, Shan’s complex relationship with Colonel Tan, the governor of Lhadrung county, is central to the narrative. Tan is as brutal and ruthless as his party masters need him to be, but there is a tiny spark of something – perhaps not integrity, but something close – which enables him to do business with Shan.

In Bones Of The Earth (the tenth and final book in the series) Shan becomes involved in a complex murder mystery involving a massive civil engineering project and a dead American.archaeology student, whose father has come to Tibet to investigate if his daughter’s death was, as the authorities declare, an unfortunate accident or something more sinister. As ever in the series, Shan’s complex relationship with Colonel Tan, the governor of Lhadrung county, is central to the narrative. Tan is as brutal and ruthless as his party masters need him to be, but there is a tiny spark of something – perhaps not integrity, but something close – which enables him to do business with Shan. he sheer intensity of the detail Pattison adds to the narrative is astonishing, particularly when he is describing the humdrum world of Yangkar. As eavesdroppers, flies on the wall or what you will, it seems a grey kind of place; the ubiquitous breeze block is everywhere, naked light bulbs swing from the ceilings and even the food – rice, noodles, vegetables, dumplings – is functional and plain. Yangkar is, of course, dwarfed by the sheer immensity of the mountain peaks and snow fields. When colour emerges it is not chromatic in a visual sense, but in the indomitable spirituality and humanity of the Tibetans themselves. Try as they might, the Chinese rarely come close to understanding or even identifying the primal bond the people of Tibet have with their religion. It is a bond partly forged in fear, but also made of a oneness with the caves, the rocks and the wild peaks where the gods – and devils – dwell.

he sheer intensity of the detail Pattison adds to the narrative is astonishing, particularly when he is describing the humdrum world of Yangkar. As eavesdroppers, flies on the wall or what you will, it seems a grey kind of place; the ubiquitous breeze block is everywhere, naked light bulbs swing from the ceilings and even the food – rice, noodles, vegetables, dumplings – is functional and plain. Yangkar is, of course, dwarfed by the sheer immensity of the mountain peaks and snow fields. When colour emerges it is not chromatic in a visual sense, but in the indomitable spirituality and humanity of the Tibetans themselves. Try as they might, the Chinese rarely come close to understanding or even identifying the primal bond the people of Tibet have with their religion. It is a bond partly forged in fear, but also made of a oneness with the caves, the rocks and the wild peaks where the gods – and devils – dwell. I doubt that Pattison (right) is on the diplomatic Christmas Card list of President Xi Jinping and, were the author to fly into Lhasa, he is unlikely to be greeted with open arms. His disdain for the charmless and monolithic mindset of The People’s Republic is obvious, but Inspector Shan has to stay alive and keep himself on the outside of the Re-education Camps. Shan reminds me of another great fictional detective who has to do business with monsters: the late Philip Kerr’s Bernie Gunther sits down with minsters such as Goebbels and Heydrich; he will even smoke a cigar with them and accept a snifter of Schnapps while, metaphorically, holding his nose. Such is Shan’s relationship with his Chinese masters. He is a realist. If he says the wrong thing he (or his imprisoned son) is dead. Raymond Chandler’s immortal words fit the Inspector very well:

I doubt that Pattison (right) is on the diplomatic Christmas Card list of President Xi Jinping and, were the author to fly into Lhasa, he is unlikely to be greeted with open arms. His disdain for the charmless and monolithic mindset of The People’s Republic is obvious, but Inspector Shan has to stay alive and keep himself on the outside of the Re-education Camps. Shan reminds me of another great fictional detective who has to do business with monsters: the late Philip Kerr’s Bernie Gunther sits down with minsters such as Goebbels and Heydrich; he will even smoke a cigar with them and accept a snifter of Schnapps while, metaphorically, holding his nose. Such is Shan’s relationship with his Chinese masters. He is a realist. If he says the wrong thing he (or his imprisoned son) is dead. Raymond Chandler’s immortal words fit the Inspector very well:

As McCallum investigates the tragedy, it becomes clear that the ship was sabotaged. But what was within its cargo that made someone think it imperative that it should never reach its destination? A party of British soldiers are on hand determined to guard the scene of the wreck from inquisitive eyes, but who is the man named Beck who is pretending to be an army officer, but is so obviously not a military man?

As McCallum investigates the tragedy, it becomes clear that the ship was sabotaged. But what was within its cargo that made someone think it imperative that it should never reach its destination? A party of British soldiers are on hand determined to guard the scene of the wreck from inquisitive eyes, but who is the man named Beck who is pretending to be an army officer, but is so obviously not a military man? If your knowledge of that period of American history is sketchy, than fret ye not. Pattison (right) provides a wealth of detail about real life events which were taking place during McCallum’s fictional quest to clear his name. I use the word ‘quest” advisedly, as the novel has a distinct Lord of The Rings feeling – “Roads go ever on”.

If your knowledge of that period of American history is sketchy, than fret ye not. Pattison (right) provides a wealth of detail about real life events which were taking place during McCallum’s fictional quest to clear his name. I use the word ‘quest” advisedly, as the novel has a distinct Lord of The Rings feeling – “Roads go ever on”.

East London cop DI Steve Fenchurch makes a welcome return for the fourth book in this popular series by Ed James (left). It is part of urban folklore that attractive female students are sometimes tempted to use their charms to attract Sugar Daddies who will help with their fees and living costs. When one such young woman is found strangled in her bedroom, Fenchurch soon discovers that she was in the pay of a notorious city gangster. With his superiors poised to pounce on him at the first sign of a professional mistake, and his family in mortal danger, Fenchurch is faced with a no-win dilemma. If he persists in finding out who killed the young woman, he will attract incoming fire from very powerful people. If he just keeps his head down and allows the investigation to drift into the ‘unsolved’ file, his bosses will have him clearing his desk and locker before he can utter the word ‘sacked’.

East London cop DI Steve Fenchurch makes a welcome return for the fourth book in this popular series by Ed James (left). It is part of urban folklore that attractive female students are sometimes tempted to use their charms to attract Sugar Daddies who will help with their fees and living costs. When one such young woman is found strangled in her bedroom, Fenchurch soon discovers that she was in the pay of a notorious city gangster. With his superiors poised to pounce on him at the first sign of a professional mistake, and his family in mortal danger, Fenchurch is faced with a no-win dilemma. If he persists in finding out who killed the young woman, he will attract incoming fire from very powerful people. If he just keeps his head down and allows the investigation to drift into the ‘unsolved’ file, his bosses will have him clearing his desk and locker before he can utter the word ‘sacked’.  This is first in what promises to be a popular series with readers who love their novels spiced with the double-dealing and other shenanigans which are part and parcel of the work of American intelligence organisations. Nathan Stone is a former CIA covert operative who has been critically wounded, and thought to be dead. But behind closed doors, he has been rehabilitated by a highly secretive government organization known as the Commission, given a new identity and appearance, and remoulded into a lethal assassin. His brief: to execute kill orders drawn up by the Commission, all in the name of national security. Turner (right) provides enough thrills to keep even the most jaded reader on their toes.

This is first in what promises to be a popular series with readers who love their novels spiced with the double-dealing and other shenanigans which are part and parcel of the work of American intelligence organisations. Nathan Stone is a former CIA covert operative who has been critically wounded, and thought to be dead. But behind closed doors, he has been rehabilitated by a highly secretive government organization known as the Commission, given a new identity and appearance, and remoulded into a lethal assassin. His brief: to execute kill orders drawn up by the Commission, all in the name of national security. Turner (right) provides enough thrills to keep even the most jaded reader on their toes. I first came across Pattison (left) and his Revolutionary Wars hero Duncan McCallum when I was writing for Crime Fiction Lover. I reviewed

I first came across Pattison (left) and his Revolutionary Wars hero Duncan McCallum when I was writing for Crime Fiction Lover. I reviewed

The book actually begins with Shan rescuing one of the aforementioned yaks, but events take a more sinister turn. An ancient grave is uncovered, but the inhabitants are unlikely bedfellows. The original occupant is a long dead priest, mummified and gilded. But his companions are the remains of a Chinese soldier, and the very recent corpse of an American visitor. There is cultural confusion when a mobile ‘phone, presumably not the property of either the priest of the soldier, chimes out Handel’s Hallelujah Chorus across the chill mountain air and into the ears of alarmed Yangkar locals.

The book actually begins with Shan rescuing one of the aforementioned yaks, but events take a more sinister turn. An ancient grave is uncovered, but the inhabitants are unlikely bedfellows. The original occupant is a long dead priest, mummified and gilded. But his companions are the remains of a Chinese soldier, and the very recent corpse of an American visitor. There is cultural confusion when a mobile ‘phone, presumably not the property of either the priest of the soldier, chimes out Handel’s Hallelujah Chorus across the chill mountain air and into the ears of alarmed Yangkar locals. masters far away to the east is described with wit and a certain degree of compassion. I am never completely convinced by the regular use of italicised foreign language nouns in novels, particularly when the original words would have used an entirely different alphabet, but this is a tiny complaint dwarfed by what is a brilliant and evocative police procedural, albeit one set in a world as far away from our European certainties as it is possible to recreate. Pattison (right) has written a novel which reminds us that China’s eminence as a world power has not been achieved painlessly.

masters far away to the east is described with wit and a certain degree of compassion. I am never completely convinced by the regular use of italicised foreign language nouns in novels, particularly when the original words would have used an entirely different alphabet, but this is a tiny complaint dwarfed by what is a brilliant and evocative police procedural, albeit one set in a world as far away from our European certainties as it is possible to recreate. Pattison (right) has written a novel which reminds us that China’s eminence as a world power has not been achieved painlessly.

SKELETON GOD by ELIOT PATTISON

SKELETON GOD by ELIOT PATTISON FATAL PURSUIT by MARTIN WALKER

FATAL PURSUIT by MARTIN WALKER AMNESIA by MICHAEL RIDPATH

AMNESIA by MICHAEL RIDPATH DEFECTORS by JOSEPH KANON

DEFECTORS by JOSEPH KANON