This is a welcome return for my favourite crime solving partnership in current fiction – 1960s Brighton reporter Colin Crampton and his delightful Australian girlfriend Shirley Goldsmith. Shirley discovers via an enigmatic letter – promising unidentified riches – that a long lost relative, Hobart Birtwhistle, has fetched up in the delightfully named Sussex village of Muddles Green, just a short spin away from Brighton in Colin’s rakish MGB. Unfortunately, when the couple arrive at half-uncle Hobart’s cottage, any avuncular reunion is prevented by the fact that the old chap is dead in his study chair, with a nasty head wound and throttle marks around his throat.

Colin and Shirley conduct their own investigation into Hobart’s murder and, as ever, it takes them far and wide, involving – amongst others – a tetchy history don with expertise in Australia’s gold rush, an eccentric Scottish lord and a team of women cricketers, not forgetting a most improbable but highly entertaining encounter with Ronnie Kray. Peter Bartram (perhaps an older real life version of Colin Crampton) never strays far away from the bedrock of these mysteries – the smoky offices and noisy print rooms of the Evening Chronicle. Crampton’s boss – the editor, Frank Figgis, perpetually wreathed in a haze of Woodbines smoke, also has a job for his chief crime reporter. Figgis, foe reasons of his own, has written a memoir, almost certainly full of dirty secrets featuring colleagues and bosses. But it has gone missing. Has the befuddled Figgis mislaid it, or has it been stolen? Figgis makes it clear that the recovery of the missing ‘blockbuster’ is to be Crampton’s chief focus.

Unfortunately, the killing of Hobart Birtwhistle is not the last in a fatal sequence that seems connected with the complex genealogy of Shirley’s obscure relatives – and a huge gold nugget discovered back in the day in Australia. Thanks to the research of the Scottish aristocrat (the real life Arthur ‘Boofy’ Gore), Shirley learns something that may well prove to be ‘to her advantage’, but may also put her name to the top of the killer’s list.

Former journalists do not always have the required skills to write good novels. Penning a 1000 word front page exclusive is not the same as writing a 300 page book. Novel readers need to be engaged long term – they don’t have the option of switching to the sports news on the back pages. Peter Bartram makes the transition with no apparent effort – he retains his journalist’s skill of boiling a narrative down to its essentials, while fleshing out the story with delightful characterisation and period detail.

Bartram’s genius lies partly in not taking himself too seriously as he tugs at our nostalgic heartstrings by recreating an impeccably convincing mid-1960s milieu, but – more potently – in having created two utterly adorable main characters who, if we couldn’t actually be them, we would at least love to have known them. At my age, current events beyond my control make me daily more choleric, and wishing for the days of common sense and decency, long since gone. But then I can retreat into a beautiful book like this, and be taken back to a kinder time, a time I understood and felt part of.

The Family Tree Mystery is published by The Bartram Partnership, and is available now. For more information on the Crampton of The Chronicle novels, click the image below.

It is 1965 and we are basking in the slightly faded grandeur of Brighton, on the south coast of England. The town has never quite recovered from its association, more than a century earlier, with the bloated decadence of The Prince Regent, and it shrugs its shoulders at the more recent notoriety bestowed by a certain crime novel brought to life on the big screen in 1947. Brighton has its present-day misdeeds too, and who better to write about it than the intrepid crime reporter for the Evening Chronicle, Colin Crampton?

It is 1965 and we are basking in the slightly faded grandeur of Brighton, on the south coast of England. The town has never quite recovered from its association, more than a century earlier, with the bloated decadence of The Prince Regent, and it shrugs its shoulders at the more recent notoriety bestowed by a certain crime novel brought to life on the big screen in 1947. Brighton has its present-day misdeeds too, and who better to write about it than the intrepid crime reporter for the Evening Chronicle, Colin Crampton? rampton is an enterprising and thoroughly likeable fellow, with a rather nice sports car and an even nicer girlfriend, in the very pleasing shape of Australian lass Shirley Goldsmith. Crampton is summoned to the office of his deputy editor Frank Figgis and, barely discernible amid the wreaths of smoke from his Woodbines, Figgis’s face is creased by more worry lines than usual. His problem? The Chronicle’s drama correspondent, Sidney Pinker, has been served with a libel writ for savaging, in print, a local theatrical agent called Daniel Bernstein.

rampton is an enterprising and thoroughly likeable fellow, with a rather nice sports car and an even nicer girlfriend, in the very pleasing shape of Australian lass Shirley Goldsmith. Crampton is summoned to the office of his deputy editor Frank Figgis and, barely discernible amid the wreaths of smoke from his Woodbines, Figgis’s face is creased by more worry lines than usual. His problem? The Chronicle’s drama correspondent, Sidney Pinker, has been served with a libel writ for savaging, in print, a local theatrical agent called Daniel Bernstein.

inker, by the way, is very much in the John Inman school of caricature luvvies, so those with an over-sensitive approach had better look away now. His pale green shirts, flowery cravats and patronage of certain Brighton nightspots are pure (politically incorrect) comedy.

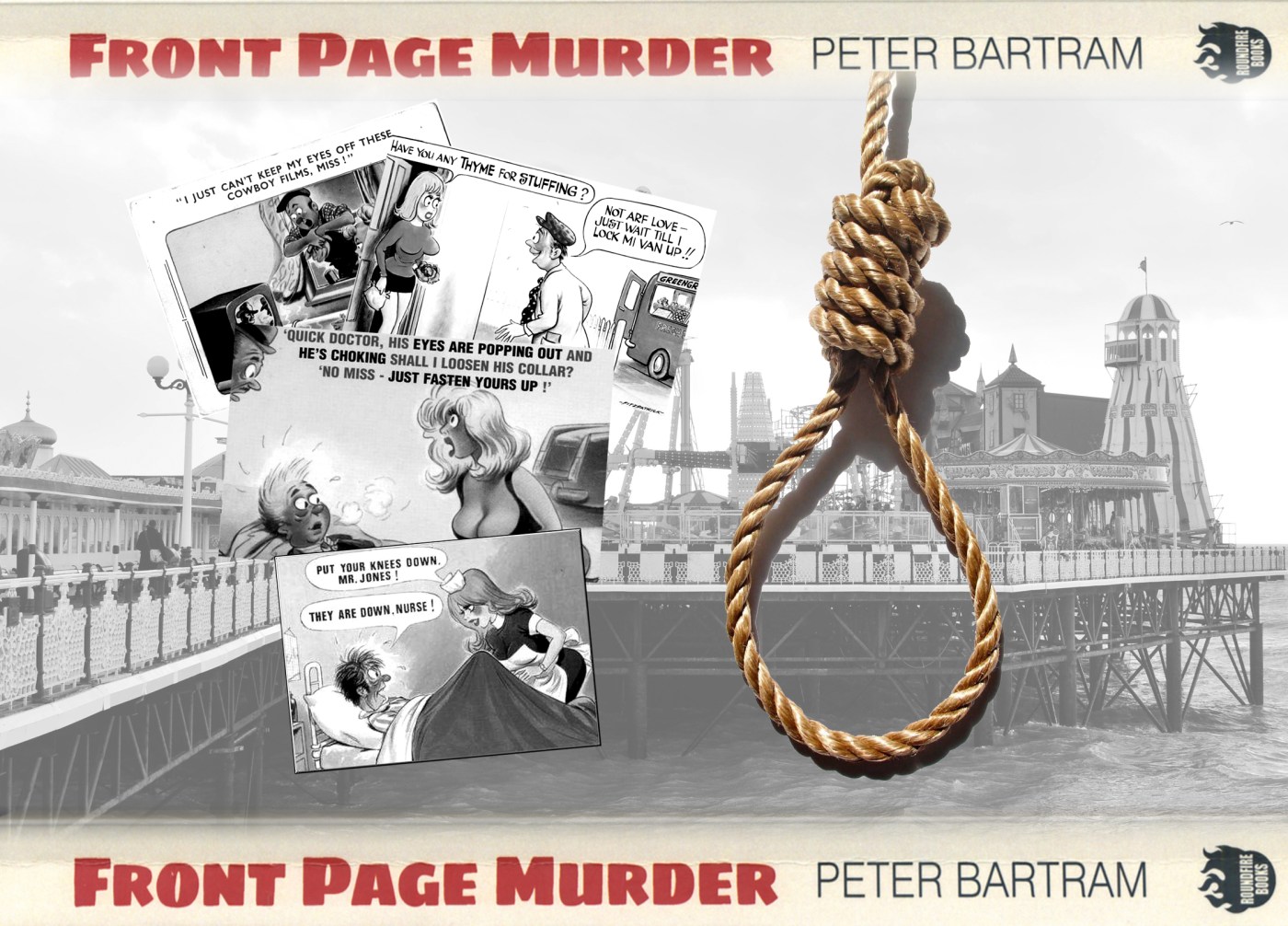

inker, by the way, is very much in the John Inman school of caricature luvvies, so those with an over-sensitive approach had better look away now. His pale green shirts, flowery cravats and patronage of certain Brighton nightspots are pure (politically incorrect) comedy. Bernstein’s murder is seen as very much open-and-shut by the Brighton coppers, but Crampton does not believe that Pinker has the mettle to commit physical violence. Instead, his investigation takes him into the rather sad world of stand-up comedians. Today, our stand-up gagsters can become millionaire celebrities, but back in 1965, the old style joke tellers with their catchphrases and patter were becoming a thing of the past, as TV satire was breaking new ground and reaching new audiences. Crampton believes that the murder of Bernstein is connected to the agent’s former association with Max Miller and, crucially, the possession of Miller’s fabled Blue Book, said to contain all of The Cheeky Chappy’s best material – and a few jokes considered too rude for polite company.

Bernstein’s murder is seen as very much open-and-shut by the Brighton coppers, but Crampton does not believe that Pinker has the mettle to commit physical violence. Instead, his investigation takes him into the rather sad world of stand-up comedians. Today, our stand-up gagsters can become millionaire celebrities, but back in 1965, the old style joke tellers with their catchphrases and patter were becoming a thing of the past, as TV satire was breaking new ground and reaching new audiences. Crampton believes that the murder of Bernstein is connected to the agent’s former association with Max Miller and, crucially, the possession of Miller’s fabled Blue Book, said to contain all of The Cheeky Chappy’s best material – and a few jokes considered too rude for polite company. here have been occasions – and I am not alone – when I have used the term cosy in a book review, meaning no ill-will by it, but perhaps suggesting a certain lack of seriousness or an avoidance of the grim details of crime. Are the Colin Crampton books cosy? Perhaps.You will search in vain for explorations of the dark corners of the human psyche, any traces of bitterness or the consuming powers of grief and anger. What you will find is humour, clever plotting, a warm sense of nostalgia and – above all – an abundance of charm. A dictionary defines that word as “the power or quality of delighting, attracting, or fascinating others.” Remember, though, that the word has another meaning, that of an apparently insignificant trinket, but one which brings the wearer a sense of well-being and even, perhaps, the power to produce something magical.

here have been occasions – and I am not alone – when I have used the term cosy in a book review, meaning no ill-will by it, but perhaps suggesting a certain lack of seriousness or an avoidance of the grim details of crime. Are the Colin Crampton books cosy? Perhaps.You will search in vain for explorations of the dark corners of the human psyche, any traces of bitterness or the consuming powers of grief and anger. What you will find is humour, clever plotting, a warm sense of nostalgia and – above all – an abundance of charm. A dictionary defines that word as “the power or quality of delighting, attracting, or fascinating others.” Remember, though, that the word has another meaning, that of an apparently insignificant trinket, but one which brings the wearer a sense of well-being and even, perhaps, the power to produce something magical.

Then there was the female comic, in the 1960s often from the north of England, like Hylda Baker. In fact, I’ve made my version – Jessie O’Mara – younger and more overtly feminist than Baker. The feminist movement was stirring in the 1960s. I’ve made O’Mara a Liverpool lass with a strong line in scouse chat.

Then there was the female comic, in the 1960s often from the north of England, like Hylda Baker. In fact, I’ve made my version – Jessie O’Mara – younger and more overtly feminist than Baker. The feminist movement was stirring in the 1960s. I’ve made O’Mara a Liverpool lass with a strong line in scouse chat.

A special kind of comic in the days of variety theatre was the ventriloquist. The most famous was Peter Brough whose dummy was Archie Andrews. The pair featured in a long-running radio show. (I could never see the point of doing a vent act any more than a juggling act on the radio.) So I’ve created Teddy Hooper and his dummy Percival Plonker who do what used to be called a cross-talk act of quick-fire gags.

A special kind of comic in the days of variety theatre was the ventriloquist. The most famous was Peter Brough whose dummy was Archie Andrews. The pair featured in a long-running radio show. (I could never see the point of doing a vent act any more than a juggling act on the radio.) So I’ve created Teddy Hooper and his dummy Percival Plonker who do what used to be called a cross-talk act of quick-fire gags.

In The Mother’s Day Mystery, Crampton discovers the body of a schoolboy who has evidently been knocked off his bike and fatally injured. What on earth was Spencer Hooke doing away from his dormitory in Steyning Grammar School at the dead of night, cycling along a lonely and windswept clifftop road? In pursuing this conundrum, Crampton whisks us into a world of stage vicars, seedy pub landlords, archetypal leather-elbowed schoolmasters and impecunious toffs. There are jokes a-plenty, and Bartram indulges himself – and those of us who are, similarly, in the autumn of our years – with many a knowing cultural reference that might puzzle younger readers. He takes us into a wonderful sweet shop, the kind which can nowadays only be found in museum recreations:

In The Mother’s Day Mystery, Crampton discovers the body of a schoolboy who has evidently been knocked off his bike and fatally injured. What on earth was Spencer Hooke doing away from his dormitory in Steyning Grammar School at the dead of night, cycling along a lonely and windswept clifftop road? In pursuing this conundrum, Crampton whisks us into a world of stage vicars, seedy pub landlords, archetypal leather-elbowed schoolmasters and impecunious toffs. There are jokes a-plenty, and Bartram indulges himself – and those of us who are, similarly, in the autumn of our years – with many a knowing cultural reference that might puzzle younger readers. He takes us into a wonderful sweet shop, the kind which can nowadays only be found in museum recreations: Anyone who is a student of English humour will soon see that Bartram is part of a long and distinguished tradition of comic writers who find meat and drink in the absurdities of English life and social structures. In the world of crime fiction, however, comedy does not always sit well with murder and bloodshed. The great and sadly under-appreciated

Anyone who is a student of English humour will soon see that Bartram is part of a long and distinguished tradition of comic writers who find meat and drink in the absurdities of English life and social structures. In the world of crime fiction, however, comedy does not always sit well with murder and bloodshed. The great and sadly under-appreciated

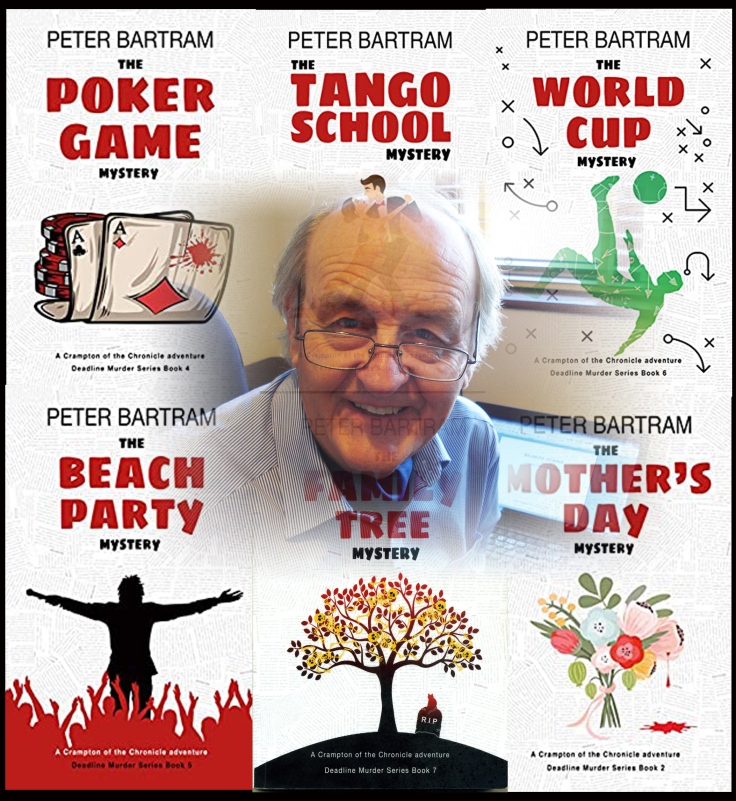

Peter Bartram (left) is an old school journalist who has turned his life’s work into an engaging crime series set in 1960s Brighton, featuring the resourceful reporter on the local paper, Colin Crampton. Peter now reveals how he came to invent his alter ego. You can read reviews of three Crampton of The Chronicle novels by clicking the title links below.

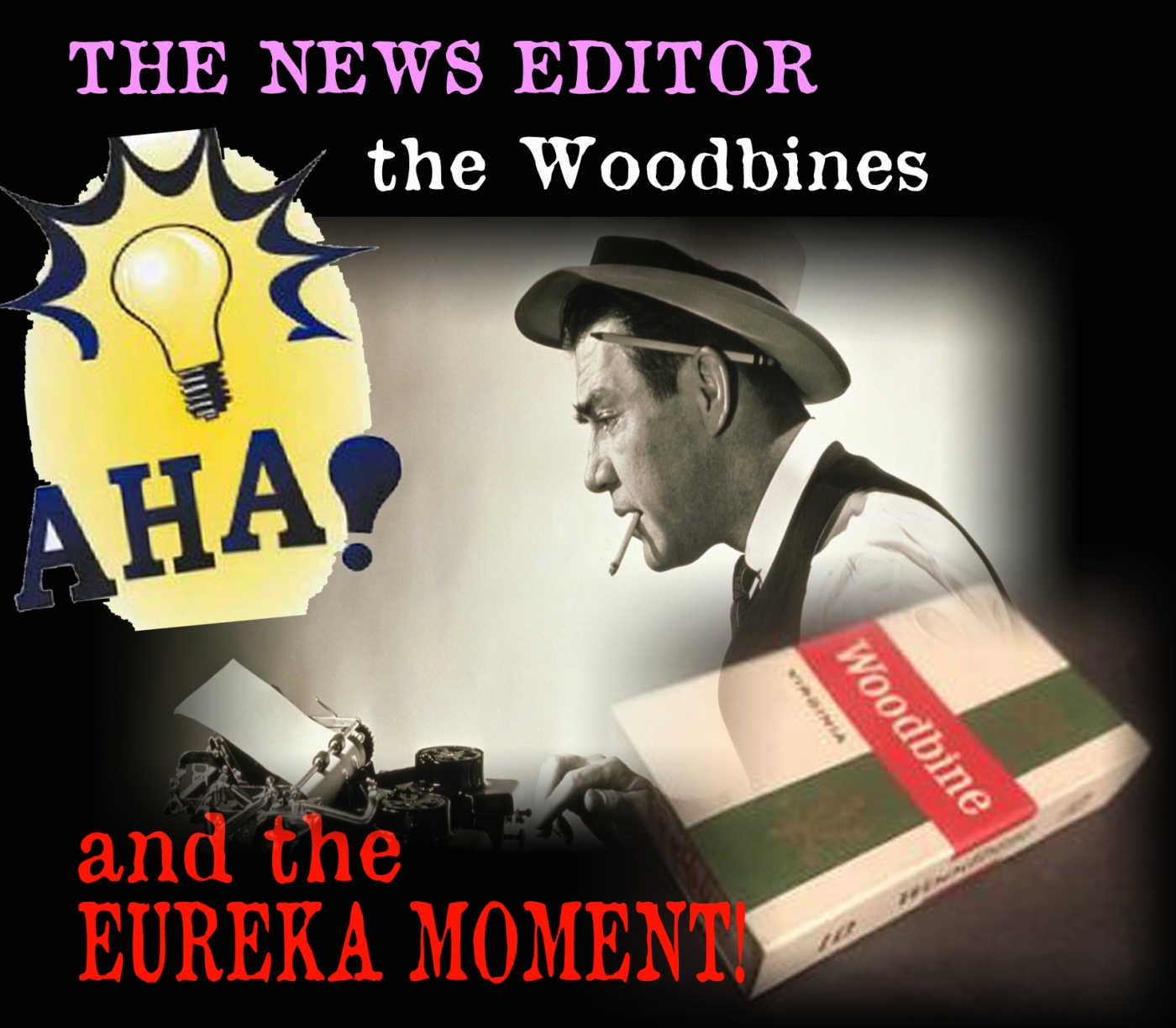

Peter Bartram (left) is an old school journalist who has turned his life’s work into an engaging crime series set in 1960s Brighton, featuring the resourceful reporter on the local paper, Colin Crampton. Peter now reveals how he came to invent his alter ego. You can read reviews of three Crampton of The Chronicle novels by clicking the title links below. And that was when I remembered my first news editor. I never saw him without a Woodbine hanging off his lower lip. And so Frank Figgis, news editor of the Evening Chronicle, was born. Of course, there was still lots to think about – especially more regular characters. But with Colin (right) and Frank I felt I was on my way. Both of them have big roles to play – along with other regulars, especially Colin’s girlfriend Shirley Goldsmith – in the latest tale The Mother’s Day Mystery.

And that was when I remembered my first news editor. I never saw him without a Woodbine hanging off his lower lip. And so Frank Figgis, news editor of the Evening Chronicle, was born. Of course, there was still lots to think about – especially more regular characters. But with Colin (right) and Frank I felt I was on my way. Both of them have big roles to play – along with other regulars, especially Colin’s girlfriend Shirley Goldsmith – in the latest tale The Mother’s Day Mystery.

In the latest novel from Peter Bartram (left) his alter ego Colin Crampton, a reporter for the Evening Chronicle in 1960s Brighton, faces his toughest challenge yet. Local artist Archie Flowerdew is due to be hanged on Christmas Eve unless Crampton and his intrepid Australian girlfriend Shirley can stop this affront to Christmas cheer by proving that Flowerdew did not murder a rival artist.

In the latest novel from Peter Bartram (left) his alter ego Colin Crampton, a reporter for the Evening Chronicle in 1960s Brighton, faces his toughest challenge yet. Local artist Archie Flowerdew is due to be hanged on Christmas Eve unless Crampton and his intrepid Australian girlfriend Shirley can stop this affront to Christmas cheer by proving that Flowerdew did not murder a rival artist. Persuaded by the condemned man’s niece, Tammy, Crampton gets to work, and finds no shortage of other Brighton folk who would have clapped their hands in glee upon hearing of Despart’s demise. The plot thickens delightfully, as we encounter a crooked art dealer, a lecherous vicar, a camp artist (complete with velvet trousers) and the usual cast of boozy, chain-smoking searchers-after-truth (or a good headline) on the staff of the Evening Chronicle.

Persuaded by the condemned man’s niece, Tammy, Crampton gets to work, and finds no shortage of other Brighton folk who would have clapped their hands in glee upon hearing of Despart’s demise. The plot thickens delightfully, as we encounter a crooked art dealer, a lecherous vicar, a camp artist (complete with velvet trousers) and the usual cast of boozy, chain-smoking searchers-after-truth (or a good headline) on the staff of the Evening Chronicle. Bartram introduces a fascinating contemporary note by featuring the Home Secretary at the time, Henry Brooke. He was appointed by Harold Macmillan after the Prime Minister’s infamous ‘Night of The Long Knives in 1962. Brooke (left) was to prove one of the least distinguished holders of the post, however, and he was pilloried without mercy by the BBC’s satirical show That Was The Week That Was. They dubbed the hapless Brooke ‘The most hated man in Britain’, and Bartram recalls their mocking phrase, “If you’re Home Secretary, you can get away with murder.”

Bartram introduces a fascinating contemporary note by featuring the Home Secretary at the time, Henry Brooke. He was appointed by Harold Macmillan after the Prime Minister’s infamous ‘Night of The Long Knives in 1962. Brooke (left) was to prove one of the least distinguished holders of the post, however, and he was pilloried without mercy by the BBC’s satirical show That Was The Week That Was. They dubbed the hapless Brooke ‘The most hated man in Britain’, and Bartram recalls their mocking phrase, “If you’re Home Secretary, you can get away with murder.”