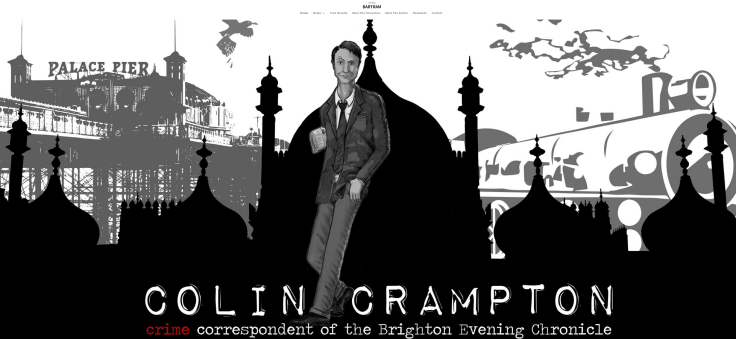

It has been, as the song goes, a long and winding road. Nearly 1000 miles, or thereabouts of rolling English highway and we are nearing the end. Just two more stops, and we will be back where we started, In London. Yes, there are places and authors we might have visited; Trevor Wood’s Newcastle, John Harvey’s Nottingham and Phil Rickman’s Hereford, to name just three. But both writer and reader can suffer fatigue, so this journey is what it is. Our penultimate stop-over is Brighton, seemingly a place of bizarre contrasts. There is the elegant watering place beloved of the Prince Regent, and the cheeky seaside town beloved of London day trippers, but with a scary undercurrent immortalised by Graham Greene. There is the contemporary Brighton, a place where outlandish political and social fads make its counterparts in California look reactionary. But our Brighton is a much sunnier place. We are in the 1960s, sex had just about been invented, mobile ‘phones were undreamt of in anyone’s philosophy, and a young man called Colin Crampton is the ace crime reporter for the Evening Chronicle.

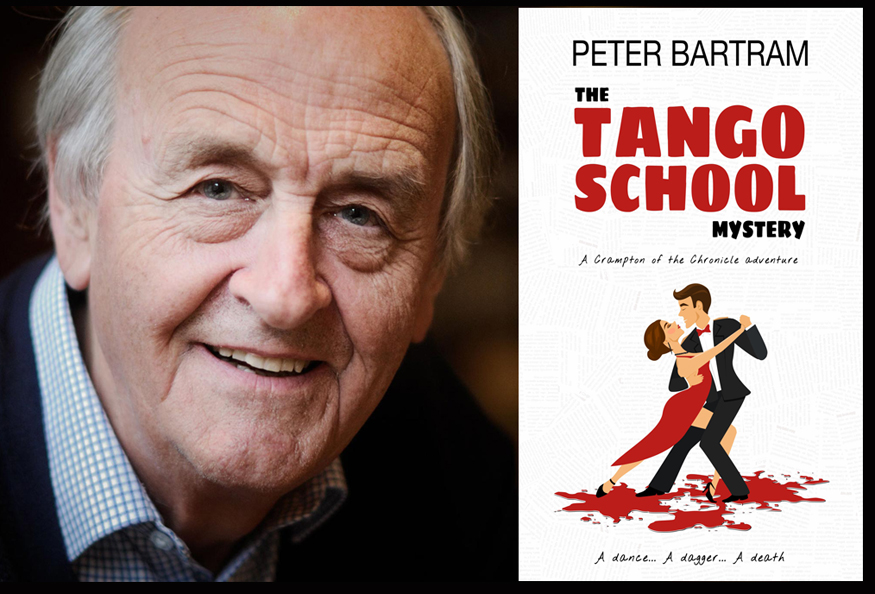

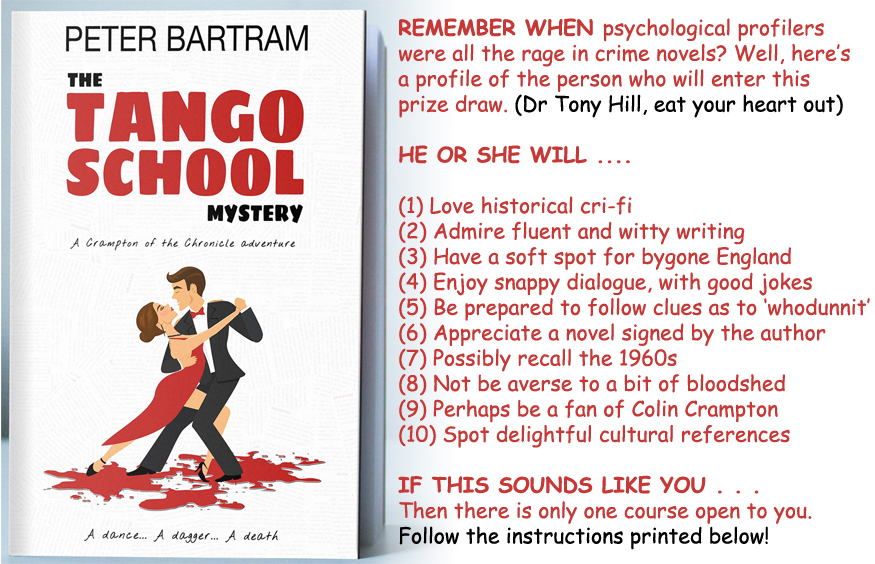

Colin Crampton is the inspired creation of former journalist Peter Bartram, and I do wonder if Colin is, perhaps, a younger version of Peter, and I would like to think so. Peter, from, my online dealings with him, is a genial and astute fellow with a broad sense of humour, and someone with a fund of nostalgic cultural references from days gone by. In brief, Colin is as sharp as a tack, has a gorgeous Australian girlfriend called Shirley, vrooms around Brighton in his sports car, and his boss, deputy editor Frank Figgis, is permanently wreathed in a cloud of Woodbines smoke. The books are simply delightful. Escapist, maybe, comfort reading, probably, but superbly crafted and endlessly entertaining – yes, yes, yes. If you click the graphic below, a link will open where you can read reviews of the Crampton of The Chronicle series, and also features by Peter on the background to some of his stories.The author’s photograph contains a link to his own website.

LONDON CALLING! And the voices are none other than those of Arthur Bryant and John May – and their creator, Christopher Fowler. Bryant & May are, of course, an in-joke from the very start. More elderly readers will remember the iconic brand of matches so familiar to those of us who grew up the middle and later years of the 20th century.

Fowler devised a brilliant concept. We have two coppers who began their investigative careers during Hitler’s war. One, Arthur Bryant, is an intellectual iconoclast, a fount of obscure knowledge, be it of Tibet, Inner Mongolia, Patagonia or the inner regions of the Hindu Kush. His expertise, however, is London. There is not a hidden river, an execution site, an ancient drovers’ trackway or site of an old graveyard that Arthur doesn’t have logged somewhere in his noggin. His colleague, John May, is slightly younger, but has adapted to the passing years. He wears decent suits, chooses conciliation rather than confrontation, and retains the razor sharp mind of his younger years. He is resolutely and remorselessly devoted to Arthur Bryant, and such is Fowler’s mastery of human chemistry that we know one could never exist without the other.

There were nineteen B & M novels, beginning with Full Dark House in 2003, plus a quartet of graphic novels and short story collections. I say ‘were’, because although Christopher Fowler (left) is still with us, those who have read London Bridge Is Falling Down (2021) will know – and I am sorry if this is a spoiler – that old age and infirmity finally catches up with the venerable pair of detectives. Where to start to talk about this series? The author himself is, as far as I can judge, a modern and cosmopolitan fellow, but his love – and knowledge – of London is all embracing. Christopher Fowler is a one-off in contemporary writing, and completely individual, but speaking as an elderly chap with many years of reading behind me, I can best put him in context with great English writers of the last 150 years or so by looking at various aspects of the novels.

There were nineteen B & M novels, beginning with Full Dark House in 2003, plus a quartet of graphic novels and short story collections. I say ‘were’, because although Christopher Fowler (left) is still with us, those who have read London Bridge Is Falling Down (2021) will know – and I am sorry if this is a spoiler – that old age and infirmity finally catches up with the venerable pair of detectives. Where to start to talk about this series? The author himself is, as far as I can judge, a modern and cosmopolitan fellow, but his love – and knowledge – of London is all embracing. Christopher Fowler is a one-off in contemporary writing, and completely individual, but speaking as an elderly chap with many years of reading behind me, I can best put him in context with great English writers of the last 150 years or so by looking at various aspects of the novels.

There is humour in the books, plenty of it and – as you might guess – it’s very English. Imagine a chain of writers which goes back to Victorian times, starting perhaps with Israel Zangwill and the Grossmith brothers. The torch is carried onwards by Wodehouse, JV Morton and – with a more abrasive edge – by Waugh. Tom Sharpe is largely forgotten now, but his anarchic view of English customs and behaviour fits in well.

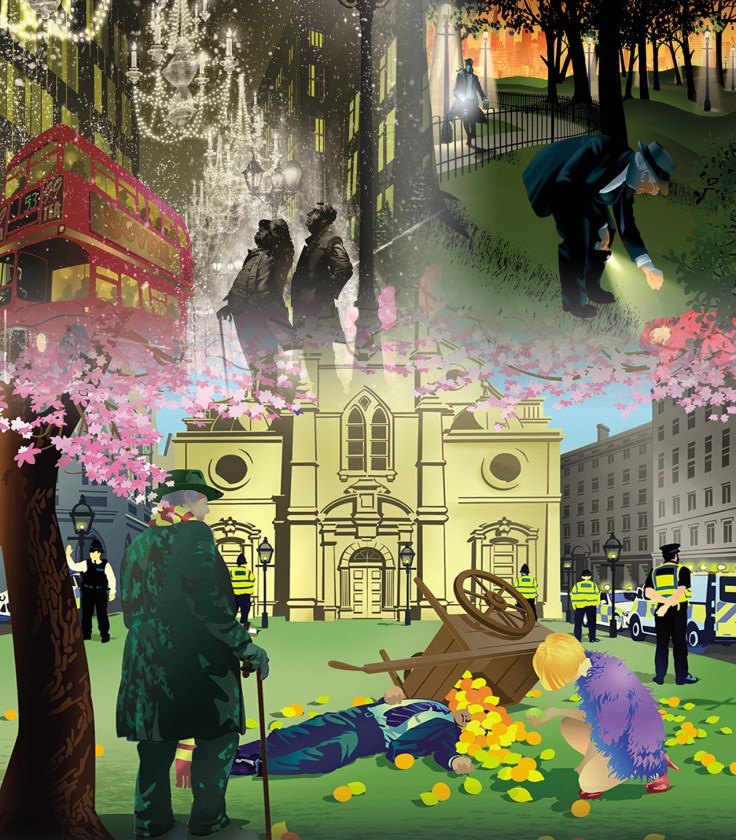

Now the city of London itself. Imagine a writer with the nostalgic fondness of Betjeman, blended with the darker imagination of writers like Ackroyd and Sinclair, and you will find that Christopher Fowler fits the bill perfectly. He makes us aware that the streets of his home town are like a stage, with troupes of actors down the ages acting out their dramas, each set of footsteps eventually fading to give way to the next, but each leaving something indelible behind, eternally available for those with ears to listen

Let’s not forget, though, that this is crime fiction, and the B&M stories have a strong vein of the Golden Age running through them, particularly with the ‘impossible’ crimes. Not content with mere locked rooms, Fowler takes us into a world where pubs vanish of the face off the earth and an 18th century highwayman commits murder in an art gallery. We started our journey in Derek Raymond’s London, with its drab streets, mean hearts, cruelty and violence. The streets walked by Bryant and May certainly have their dark corners, but Christopher Fowler fills them with joyful quirks of history, ghosts (mainly benevolent) and a sense of gleeful iconoclasm.

For reviews and features about the Bryant and May novels,

click the image below.

We are in Sicily, and it is the long hot summer of 1966. Brighton crime reporter Colin Crampton has taken his Aussie girlfriend Shirley Goldsmith abroad for a holiday. While the sun beats down, and gentle breezes blow in from the Mediterranean, Colin hopes to choose a romantic location – perhaps the ruin of a Greek temple – where he will go down on one knee and propose marriage to the beautiful Shirl. He has an expensive diamond ring in his pocket to help boost his case, but it is not to be.

We are in Sicily, and it is the long hot summer of 1966. Brighton crime reporter Colin Crampton has taken his Aussie girlfriend Shirley Goldsmith abroad for a holiday. While the sun beats down, and gentle breezes blow in from the Mediterranean, Colin hopes to choose a romantic location – perhaps the ruin of a Greek temple – where he will go down on one knee and propose marriage to the beautiful Shirl. He has an expensive diamond ring in his pocket to help boost his case, but it is not to be.

istorical crime fiction is all the more accessible when the history is recent enough for readers such as I to recognise it as authentic, and give a nostalgic sigh when some piece of popular consumer ephemera – a brand of chocolate, a radio programme or a make of car – crops up in the narrative. Colin Crampton may possibly be the autobiographical alter ego of author Peter Bartram, himself a distinguished and experienced journalist who remembers the deafening sound of the printing presses, the smell of ink, the jangle of telephones in the press room, the scratch of a pen on the paper of a notebook, and the overiding miasma of Woodbines and Senior Service drifting on the air. The Poker Game Mystery is the latest episode in the eventful career of Colin Crampton, crime reporter for the Brighton Evening Chronicle.

istorical crime fiction is all the more accessible when the history is recent enough for readers such as I to recognise it as authentic, and give a nostalgic sigh when some piece of popular consumer ephemera – a brand of chocolate, a radio programme or a make of car – crops up in the narrative. Colin Crampton may possibly be the autobiographical alter ego of author Peter Bartram, himself a distinguished and experienced journalist who remembers the deafening sound of the printing presses, the smell of ink, the jangle of telephones in the press room, the scratch of a pen on the paper of a notebook, and the overiding miasma of Woodbines and Senior Service drifting on the air. The Poker Game Mystery is the latest episode in the eventful career of Colin Crampton, crime reporter for the Brighton Evening Chronicle. One of the many joys of the Colin Crampton novels is that Peter Bartram usually manages to set the tales against actual circumstances appropriate to the period and, sometimes, we have a very thinly disguised version of a real person. In this case, we meet an outlandish minor aristocrat, heir to daddy’s millions but, more luridly, a fancier of young women. He collects them, rather like a lepidopterist collects butterflies, but rather than sticking his prizes into a display case with a pin, he keeps his young lovelies in cottages the length and breadth of the extensive estate, and has managed to organise one for each day of the week. For the life of me, I can’t think of whom Peter might have as his template for this roué, but I expect it will come to me in the middle of the night, rather like Ms Monday and the others do to their lord and master.

One of the many joys of the Colin Crampton novels is that Peter Bartram usually manages to set the tales against actual circumstances appropriate to the period and, sometimes, we have a very thinly disguised version of a real person. In this case, we meet an outlandish minor aristocrat, heir to daddy’s millions but, more luridly, a fancier of young women. He collects them, rather like a lepidopterist collects butterflies, but rather than sticking his prizes into a display case with a pin, he keeps his young lovelies in cottages the length and breadth of the extensive estate, and has managed to organise one for each day of the week. For the life of me, I can’t think of whom Peter might have as his template for this roué, but I expect it will come to me in the middle of the night, rather like Ms Monday and the others do to their lord and master. hen the body of a widely disliked local bouncer is found – his face a rictus of horror and agony – with a suspiciously large sum of used notes beside him, Crampton is sucked into a case which involves a shadowy WW2 home defence unit known as The Scallywags. Crampton discovers that they were a strange combination of Dad’s Army and the SAS – trained to wreak havoc on the Germans should they ever succeed in invading Britain. To enliven matters further, the aforementioned noble Lothario becomes the new owner of The Chronicle on the death of his father, but then promptly signs away the paper as a stake in a losing card game, this threatening the existence of The Chronicle – and those who sail in her.

hen the body of a widely disliked local bouncer is found – his face a rictus of horror and agony – with a suspiciously large sum of used notes beside him, Crampton is sucked into a case which involves a shadowy WW2 home defence unit known as The Scallywags. Crampton discovers that they were a strange combination of Dad’s Army and the SAS – trained to wreak havoc on the Germans should they ever succeed in invading Britain. To enliven matters further, the aforementioned noble Lothario becomes the new owner of The Chronicle on the death of his father, but then promptly signs away the paper as a stake in a losing card game, this threatening the existence of The Chronicle – and those who sail in her. ided by his feisty (and rather beautiful) Australian girlfriend, Crampton is up to his neck in a sea of trouble involving, among other things, dead bodies, wartime gold bullion, a predatory newspaper baron, and the arcane skill of doctoring a set of playing cards. It’s wonderful stuff – not just a crime caper, but another fine novel from a writer who wears his learning lightly.

ided by his feisty (and rather beautiful) Australian girlfriend, Crampton is up to his neck in a sea of trouble involving, among other things, dead bodies, wartime gold bullion, a predatory newspaper baron, and the arcane skill of doctoring a set of playing cards. It’s wonderful stuff – not just a crime caper, but another fine novel from a writer who wears his learning lightly. Colin Crampton’s Brighton is slightly down at heel but all the more charming for not yet having succumbed to the deadening hand which has now made it the world capital of all things green, ‘woke’, diverse and inclusive. There are still saucy postcards to be bought at the sea-front newsagent, and incorrect jokes to be delivered by Brylcreemed comedians in faded variety halls. Peter Bartram (right) has set the bar very high with his previous Crampton novels but he just gets better and better, and The Poker Game Mystery clears that bar with loads to spare. We even have a finale worthy of Indiana Jones, albeit in a murky tunnel somewhere in Sussex rather than in some more exotic location. A word of warning. If the words Atrax Robustus make you feel queasy, then you might need someone to mop your fearful brow while you read the final pages. Clue – not all of Australia’s exports are as cuddly as Crampton’s gorgeous girlfriend, Shirley Goldsmith.

Colin Crampton’s Brighton is slightly down at heel but all the more charming for not yet having succumbed to the deadening hand which has now made it the world capital of all things green, ‘woke’, diverse and inclusive. There are still saucy postcards to be bought at the sea-front newsagent, and incorrect jokes to be delivered by Brylcreemed comedians in faded variety halls. Peter Bartram (right) has set the bar very high with his previous Crampton novels but he just gets better and better, and The Poker Game Mystery clears that bar with loads to spare. We even have a finale worthy of Indiana Jones, albeit in a murky tunnel somewhere in Sussex rather than in some more exotic location. A word of warning. If the words Atrax Robustus make you feel queasy, then you might need someone to mop your fearful brow while you read the final pages. Clue – not all of Australia’s exports are as cuddly as Crampton’s gorgeous girlfriend, Shirley Goldsmith.

“When theatrical agent Daniel Bernstein sues the Evening Chronicle for libel, crime reporter Colin Crampton is called in to sort out the problem.

“When theatrical agent Daniel Bernstein sues the Evening Chronicle for libel, crime reporter Colin Crampton is called in to sort out the problem.

Colin’s day has already been bad enough. He has been summoned to the office of Frank Figgis, the News Editor, and given a daunting task. The newspaper’s Editor, Pope by name (dubbed “His Holiness”, naturally) has a brother called Gervaise. Gervaise is in trouble. He has been mixing with some rather unsavoury characters, namely the adherents of Sir Oscar Maundsley, the aristocratic former fascist leader. Interned by Churchill during the war, he now dreams of Making Britain Great Again.

Colin’s day has already been bad enough. He has been summoned to the office of Frank Figgis, the News Editor, and given a daunting task. The newspaper’s Editor, Pope by name (dubbed “His Holiness”, naturally) has a brother called Gervaise. Gervaise is in trouble. He has been mixing with some rather unsavoury characters, namely the adherents of Sir Oscar Maundsley, the aristocratic former fascist leader. Interned by Churchill during the war, he now dreams of Making Britain Great Again.

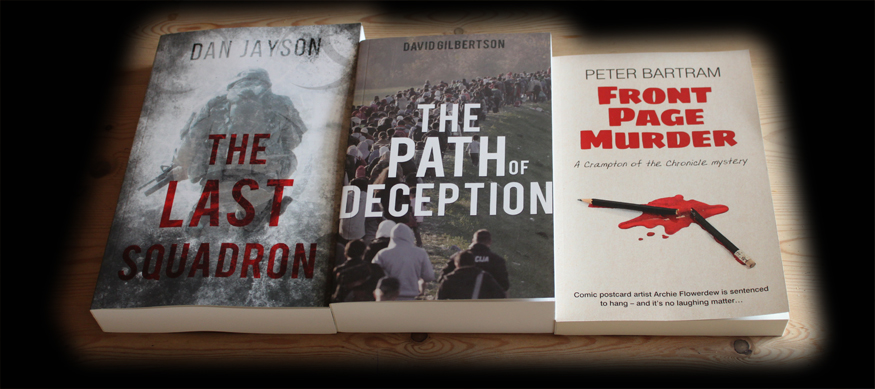

The Last Squadron is a military thriller from debut author Dan Jayson, and it is set fifteen years from now, and the most pessimistic soothsayers have been proved right. The ethnic and religious schisms which had been festering for decades have bloomed into an apocalyptic hell of different wars across the globe. Nowhere is safe, and unlikely political alliances have been forged. A squadron of mountain troops has been serving on the inhospitable Northern Front, but as they fly home for much needed rest, their aircraft is shot down – and they realise that their nightmare is only just beginning. Dan Jayson’s bio tells us that he is the co-founder of an underwater search and salvage company. He is a Fellow of the Institute of Marine Engineers and served in the British Territorial Army. He is based in south-west London.The Last Squadron is published by Matador, and is

The Last Squadron is a military thriller from debut author Dan Jayson, and it is set fifteen years from now, and the most pessimistic soothsayers have been proved right. The ethnic and religious schisms which had been festering for decades have bloomed into an apocalyptic hell of different wars across the globe. Nowhere is safe, and unlikely political alliances have been forged. A squadron of mountain troops has been serving on the inhospitable Northern Front, but as they fly home for much needed rest, their aircraft is shot down – and they realise that their nightmare is only just beginning. Dan Jayson’s bio tells us that he is the co-founder of an underwater search and salvage company. He is a Fellow of the Institute of Marine Engineers and served in the British Territorial Army. He is based in south-west London.The Last Squadron is published by Matador, and is  David Gilbertson (right) is a writer whose knowledge of policing and counter-terrorism is second to none. He had a long and varied career as a police officer. He served in uniform and CID in the UK and abroad, (attached to the New York City Police Department in 1988 and seconded to South Africa in 1994 as the Director of Peace Monitors for the first post-Apartheid elections). His latest novel, The Path of Deception, is set in a Britain devastated by a terrorist atrocity of hitherto unimagined scale. The police and security services are faced with the very real possibility that their attempts to prevent the outrage have been sabotaged from within. Suddenly, the task of making safe the imminent coronation of King Charles III is thrown into a very different focus. You can read more on the

David Gilbertson (right) is a writer whose knowledge of policing and counter-terrorism is second to none. He had a long and varied career as a police officer. He served in uniform and CID in the UK and abroad, (attached to the New York City Police Department in 1988 and seconded to South Africa in 1994 as the Director of Peace Monitors for the first post-Apartheid elections). His latest novel, The Path of Deception, is set in a Britain devastated by a terrorist atrocity of hitherto unimagined scale. The police and security services are faced with the very real possibility that their attempts to prevent the outrage have been sabotaged from within. Suddenly, the task of making safe the imminent coronation of King Charles III is thrown into a very different focus. You can read more on the  Crime reporter Colin Crampton (as imagined by Frank Duffy, left) is a delightful invention by journalist and author Peter Bartram. Only he could verify the extent to which Colin is autobiographical, but suffice it to say that Bartram has spent in his working life in journalism, and knows Brighton in and out, top to bottom, and backwards and forwards. In Front Page Murder, Crampton once again becomes involved in a very literal matter of life and death. Set in the 1960s before the abolition of the death penalty, Crampton is persuaded to establish the innocence of Archie Flowerdew – awaiting the hangman’s noose for the murder of a rival artist. Peter Bartram wrote an excellent piece for Fully Booked on the peculiarly English attraction known as What The Butler Saw machines, and you can read the entertaining feature

Crime reporter Colin Crampton (as imagined by Frank Duffy, left) is a delightful invention by journalist and author Peter Bartram. Only he could verify the extent to which Colin is autobiographical, but suffice it to say that Bartram has spent in his working life in journalism, and knows Brighton in and out, top to bottom, and backwards and forwards. In Front Page Murder, Crampton once again becomes involved in a very literal matter of life and death. Set in the 1960s before the abolition of the death penalty, Crampton is persuaded to establish the innocence of Archie Flowerdew – awaiting the hangman’s noose for the murder of a rival artist. Peter Bartram wrote an excellent piece for Fully Booked on the peculiarly English attraction known as What The Butler Saw machines, and you can read the entertaining feature