A trip to Scunthorpe might not be too high on many people’s list of literary pilgrimages, but we are calling in for a very good reason, and that is because it was the probable setting for one of the great crime novels, which was turned into a film which regularly appears in the charts of “Best Film Ever”. I am talking about Jack’s Return Home, better known as Get Carter. Hang on, hang on – that was in Newcastle wasn’t it? Yes, the film was, but director Mike Hodges recognised that Newcastle had a more gritty allure in the public’s imagination than the north Lincolnshire steel town, which has long been the butt of gags in the stage routine of stand-up comedians.

A trip to Scunthorpe might not be too high on many people’s list of literary pilgrimages, but we are calling in for a very good reason, and that is because it was the probable setting for one of the great crime novels, which was turned into a film which regularly appears in the charts of “Best Film Ever”. I am talking about Jack’s Return Home, better known as Get Carter. Hang on, hang on – that was in Newcastle wasn’t it? Yes, the film was, but director Mike Hodges recognised that Newcastle had a more gritty allure in the public’s imagination than the north Lincolnshire steel town, which has long been the butt of gags in the stage routine of stand-up comedians.

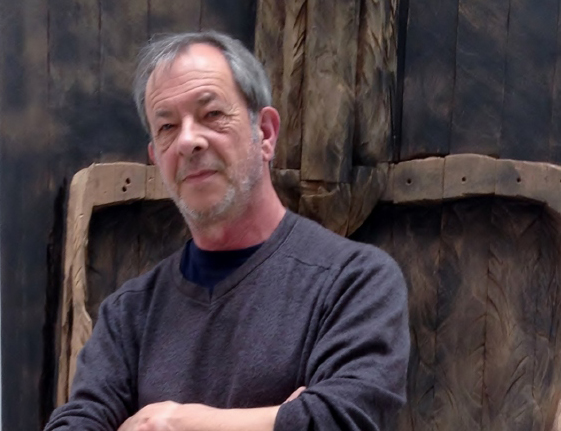

Author Ted Lewis (right) was actually born in Manchester in 1940, but after the war his parents moved to Barton-on-Humber, just fourteen miles from Scunthorpe. Lewis crossed  the river to attend Art college in Hull before moving to London to work as an animator. His novels brought him great success but little happiness, and after his marriage broke up, he moved back to Lincolnshire to live with his mother. By then he was a complete alcoholic and he died of related causes in 1982. His final novel GBH (1980) – which many critics believe to be his finest – is played out in the bleak out-of-season Lincolnshire coastal seaside resorts which Lewis would have known in the sunnier days of his childhood. In case you were wondering about how Jack’s Return Home is viewed in the book world, you can pick up a first edition if you have a spare £900 or so in your back pocket.

the river to attend Art college in Hull before moving to London to work as an animator. His novels brought him great success but little happiness, and after his marriage broke up, he moved back to Lincolnshire to live with his mother. By then he was a complete alcoholic and he died of related causes in 1982. His final novel GBH (1980) – which many critics believe to be his finest – is played out in the bleak out-of-season Lincolnshire coastal seaside resorts which Lewis would have known in the sunnier days of his childhood. In case you were wondering about how Jack’s Return Home is viewed in the book world, you can pick up a first edition if you have a spare £900 or so in your back pocket.

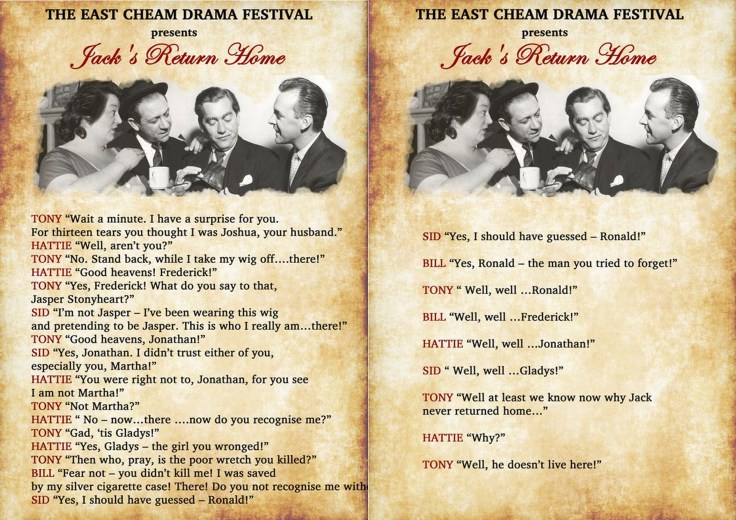

There is a rather arcane conversation to be had about the original name Jack’s Return Home. Yes, Carter’s name is Jack, and he returns to his home town to investigate the death of his brother. But take a look at a scene in the film. Carter visits his late brother’s house, and amid the books and LPs strewn about, there is a very visible copy of a Tony Hancock record, Check out the discography of Tony Hancock LPs, and you will find a recording of The East Cheam Drama Festival and one of the plays – a brilliantly spoof of a Victorian melodrama – is called …….. Jack’s Return Home.

You can find out much more about Ted Lewis and his books by clicking the image below.

Before we leave the delights of ‘Scunny’, here’s a pub quiz question. Three England captains played for which Lincolshire football team? The answer, of course, is Scunthorpe United. The three captains?

Kevin Keegan – Scunthorpe 1966-71, England captain 1976-82

Ray Clemence – Scunthorpe 1965-67, England captain once, in a friendly against Brazil

Ian Botham – Scunthorpe 1980-85, England (cricket) captain 1980-81

Ouch! Anyway, back to crime fiction and we start up the Bentley and head into darkest Yorkshire to meet a policeman and his family in the city of Leeds.

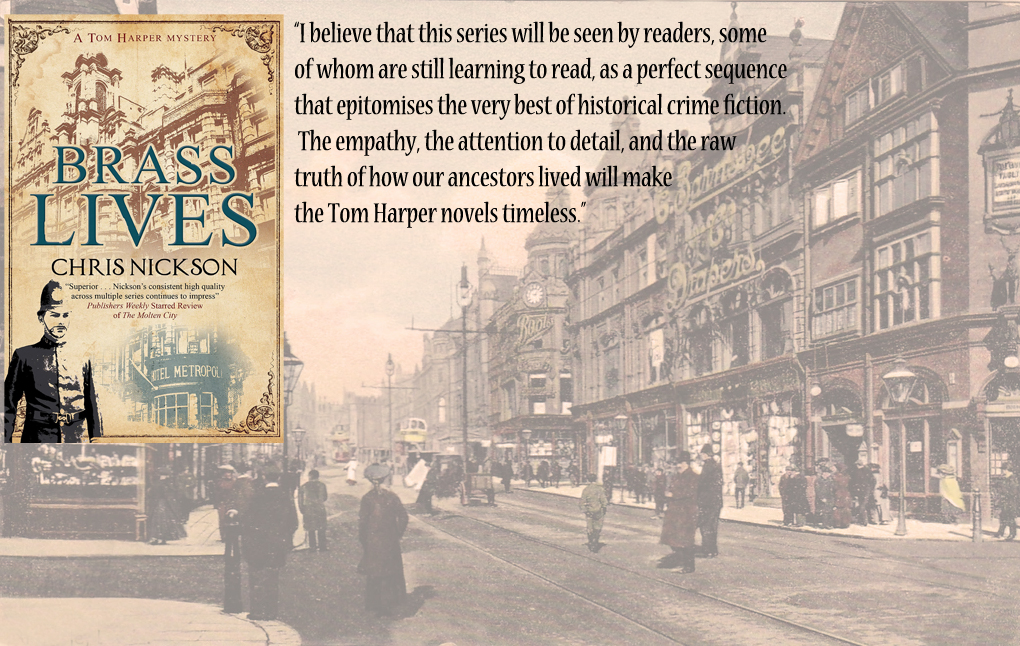

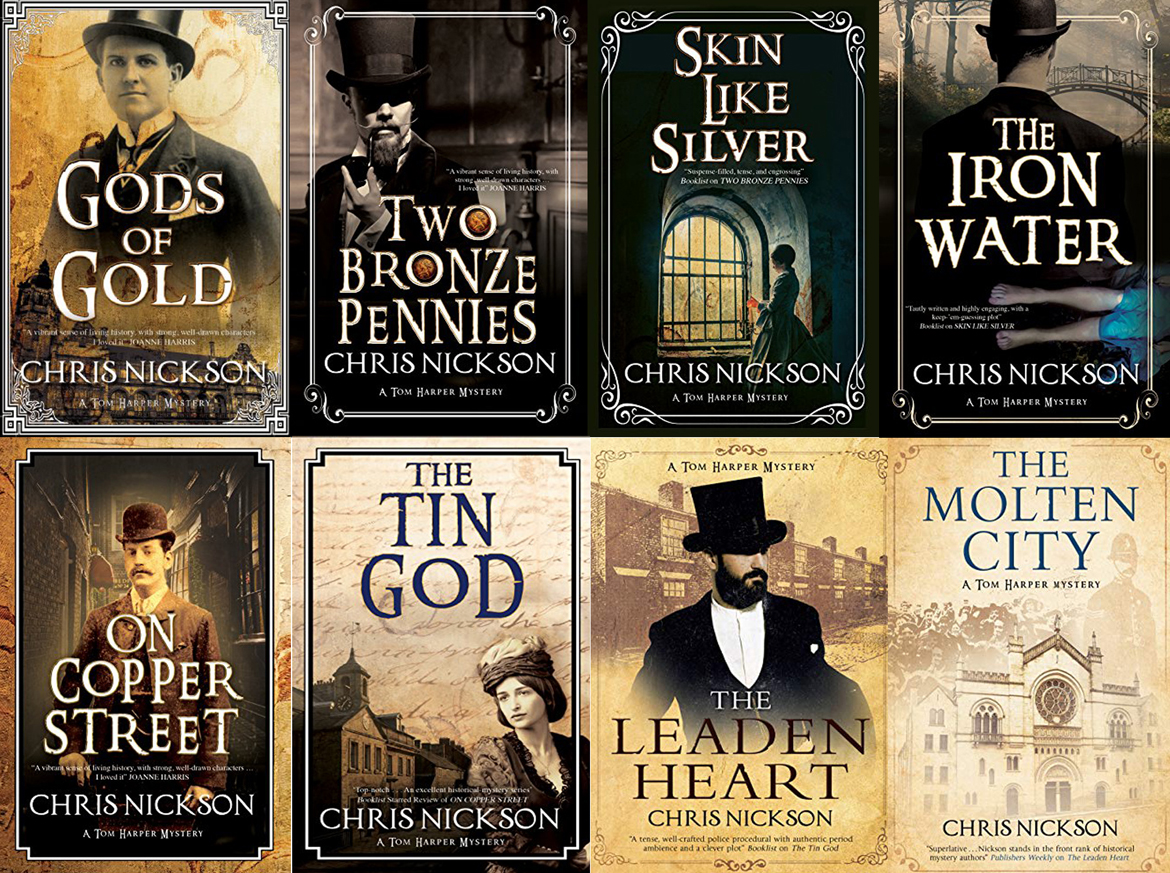

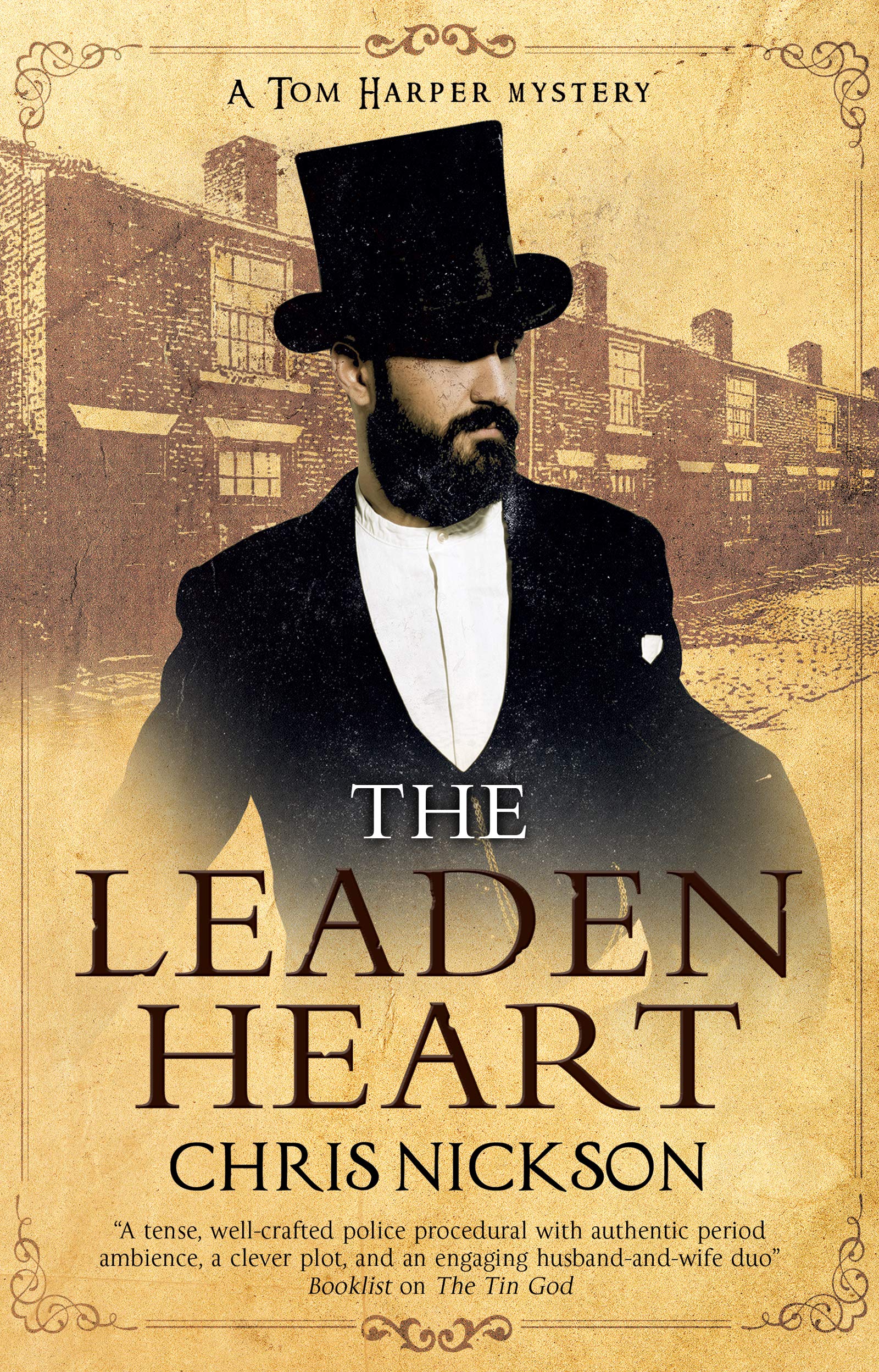

Does Chris Nickson preach? Absolutely not. This is the beauty of the Tom Harper books. No matter what the circumstances, we trust Harper’s judgment, and we can only be grateful that the struggles and sacrifices that he and his wife endured paid – eventually – dividends. The books are relatively short, but always vibrant with local historical detail, and I swear that I my eyes itch with the tang of effluent from the tanneries, and the sulphurous smoke from the foundries. We also meet real people like Herbert Asquith, Jennie Baines and Frank Kitson. Chris Nickson takes them from the dry pages of the history books and allows our imagination to bring them to life. For detailed reviews of some of the Tom Harper books, click the author’s image (left)

Does Chris Nickson preach? Absolutely not. This is the beauty of the Tom Harper books. No matter what the circumstances, we trust Harper’s judgment, and we can only be grateful that the struggles and sacrifices that he and his wife endured paid – eventually – dividends. The books are relatively short, but always vibrant with local historical detail, and I swear that I my eyes itch with the tang of effluent from the tanneries, and the sulphurous smoke from the foundries. We also meet real people like Herbert Asquith, Jennie Baines and Frank Kitson. Chris Nickson takes them from the dry pages of the history books and allows our imagination to bring them to life. For detailed reviews of some of the Tom Harper books, click the author’s image (left)

We first met Leeds policeman Tom Harper in Gods of Gold (2014) when he was a young CID officer, and the land was still ruled by Queen Victoria. Now, in The Molten City, Harper is a Superintendent and the Queen is seven years dead. ‘Bertie’ – Edward VII – is King, and England is a different place. Leeds, though, is still a thriving hub of heavy industry, pulsing with the throb of heavy machinery. And it remains grimy, soot blackened and with pockets of degradation and poverty largely ignored by the wealthy middle classes. But there are motor cars on the street, and the police have telephones. Other things are stirring, too. Not all women are content to remain second class citizens, and pressure is being put on politicians to consider giving women the vote. Sometimes this is a peaceful attempt to change things, but other women are prepared to go to greater lengths.

We first met Leeds policeman Tom Harper in Gods of Gold (2014) when he was a young CID officer, and the land was still ruled by Queen Victoria. Now, in The Molten City, Harper is a Superintendent and the Queen is seven years dead. ‘Bertie’ – Edward VII – is King, and England is a different place. Leeds, though, is still a thriving hub of heavy industry, pulsing with the throb of heavy machinery. And it remains grimy, soot blackened and with pockets of degradation and poverty largely ignored by the wealthy middle classes. But there are motor cars on the street, and the police have telephones. Other things are stirring, too. Not all women are content to remain second class citizens, and pressure is being put on politicians to consider giving women the vote. Sometimes this is a peaceful attempt to change things, but other women are prepared to go to greater lengths.

The Familiars

The Familiars Chris Nickson’s historical novels may be narrow in geographical scope – they are mostly set in Leeds across the centuries – but they are magnificent in their emotional, political and social breadth. In

Chris Nickson’s historical novels may be narrow in geographical scope – they are mostly set in Leeds across the centuries – but they are magnificent in their emotional, political and social breadth. In  SW Perry has written an excellent thriller about religious extremism, media manipulation and political treachery. The fact that

SW Perry has written an excellent thriller about religious extremism, media manipulation and political treachery. The fact that  For all that the era was in my lifetime, the 1950s may just as well be the 1650s given the gulf between then and the modern world. In

For all that the era was in my lifetime, the 1950s may just as well be the 1650s given the gulf between then and the modern world. In

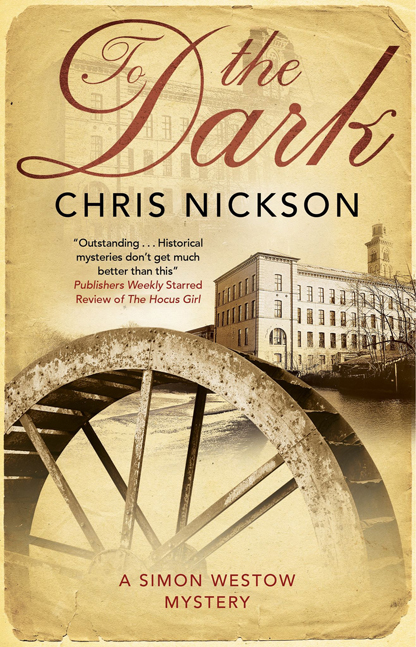

t was not until the middle of the nineteenth century that Britain had anything like an organised police force. The Hocus Girl is set well before that time, and even a developing community like Leeds relied largely on local Constables and The Watch – both institutions being badly paid, unsupported and mostly staffed by elderly individuals who would dodder a mile to avoid any form of trouble or confrontation. There were, however, men known as Thieftakers. The title is self-explanatory. They were men who knew how to handle themselves. They were employed privately, and were outside of the rudimentary criminal justice system.

t was not until the middle of the nineteenth century that Britain had anything like an organised police force. The Hocus Girl is set well before that time, and even a developing community like Leeds relied largely on local Constables and The Watch – both institutions being badly paid, unsupported and mostly staffed by elderly individuals who would dodder a mile to avoid any form of trouble or confrontation. There were, however, men known as Thieftakers. The title is self-explanatory. They were men who knew how to handle themselves. They were employed privately, and were outside of the rudimentary criminal justice system. Such a man is Simon Westow. He is paid, cash in hand, to recover stolen goods, by whatever means necessary. His home town of Leeds is changing at an alarming rate as mechanised cloth mills replace the cottage weavers, and send smoke belching into the sky and chemicals into the rivers. We first met Westow in The Hanging Psalm, and there we were also introduced to young woman called Jane. She is a reject, a loner, and she is also prone to what we now call self-harm. She is a girl of the streets, but not in a sexual way; she knows every nook, cranny, and ginnel of the city; as she shrugs herself into her shawl, she can become invisible and anonymous. Her sixth sense for recognising danger and her capacity for violence – usually via a wickedly honed knife – makes her an invaluable ally to Westow. I have spent many enjoyable hours reading the author’s books, and it is my view that Jane is the darkest and most complex character he has created. In many ways The Hocus Girl is all about her.

Such a man is Simon Westow. He is paid, cash in hand, to recover stolen goods, by whatever means necessary. His home town of Leeds is changing at an alarming rate as mechanised cloth mills replace the cottage weavers, and send smoke belching into the sky and chemicals into the rivers. We first met Westow in The Hanging Psalm, and there we were also introduced to young woman called Jane. She is a reject, a loner, and she is also prone to what we now call self-harm. She is a girl of the streets, but not in a sexual way; she knows every nook, cranny, and ginnel of the city; as she shrugs herself into her shawl, she can become invisible and anonymous. Her sixth sense for recognising danger and her capacity for violence – usually via a wickedly honed knife – makes her an invaluable ally to Westow. I have spent many enjoyable hours reading the author’s books, and it is my view that Jane is the darkest and most complex character he has created. In many ways The Hocus Girl is all about her. he 1820s were a time of great domestic upheaval in Britain. The industrial revolution was in its infancy but was already turning society on its head. The establishment was wary of challenge, and when Davey Ashton, a Leeds man with revolutionary ideas is arrested, Simon Westow – a long time friend – comes to his aid. As Ashton languishes in the filthy cell beneath Leeds Moot Hall, Westow discovers that he is treading new ground – political conspiracy and the work of an agent provocateur.

he 1820s were a time of great domestic upheaval in Britain. The industrial revolution was in its infancy but was already turning society on its head. The establishment was wary of challenge, and when Davey Ashton, a Leeds man with revolutionary ideas is arrested, Simon Westow – a long time friend – comes to his aid. As Ashton languishes in the filthy cell beneath Leeds Moot Hall, Westow discovers that he is treading new ground – political conspiracy and the work of an agent provocateur.

Harper lives above a city pub, the Victoria. His wife, Annabelle, is the landlady, but she is also a fiercely determined advocate of women’s rights, and she has made waves by being elected to the local Board of Guardians, a largely male-dominated organisation which is tasked with administering what, in the dying years of Queen Victoria’s reign, passed for social care. When the brother of Harper’s one-time colleague, Billy Reed, commits suicide the death is dismissed, albeit sadly, as commonplace, but Reed believes that his brother’s death is due to something more sinister, and he asks Harper to investigate.

Harper lives above a city pub, the Victoria. His wife, Annabelle, is the landlady, but she is also a fiercely determined advocate of women’s rights, and she has made waves by being elected to the local Board of Guardians, a largely male-dominated organisation which is tasked with administering what, in the dying years of Queen Victoria’s reign, passed for social care. When the brother of Harper’s one-time colleague, Billy Reed, commits suicide the death is dismissed, albeit sadly, as commonplace, but Reed believes that his brother’s death is due to something more sinister, and he asks Harper to investigate.