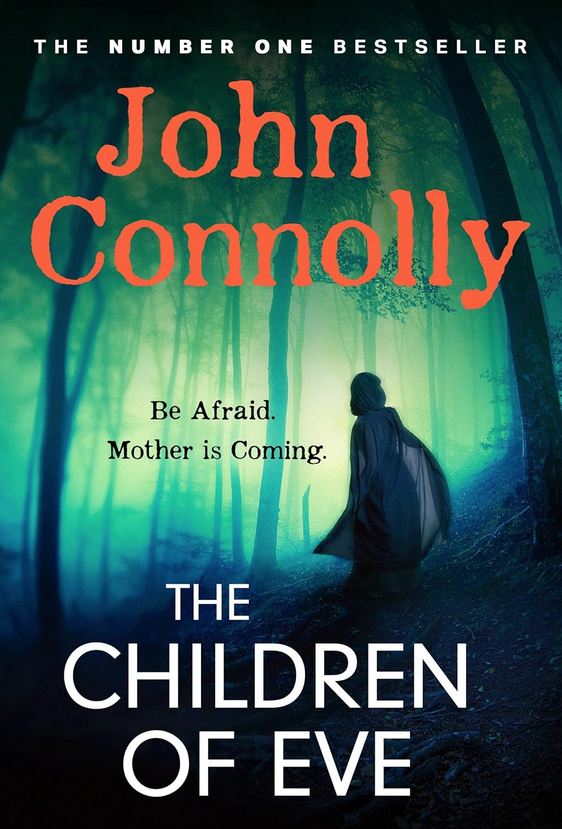

John Connolly, just like his great predecessor MR James knows what scares us. Although James had a cupboard full of spectres at his disposal, he knew the visceral fear many of us have of dry, clicking, leathery things that may be actually alive – or long dead. Arachnids, and things like them, can be fearsome. Remember the creatures that dwelt in the eponymous The Ash Tree? Across the Charlie Parker canon, Connolly has often introduced the spider – usually something truly nasty like the Brown Recluse – as evidence that evil is abroad. Here, just nine pages in, a relatively honest Mexican antique dealer, Antonio Elizalde, has resorted to finding and selling something (we have let to yearn what) truly astonishing to pay for expensive private medical care. The night before he is due to fly north to begin treatment, he buys everyone in the bar a tequila, and walks home. What he finds when he unlocks his front door will have every registered arachnophobe trembling. I had to read the next few pages, but I didn’t want to.

Incidentally, Connolly doesn’t expect his readers to be deeply immersed in Meso-American history, but he knows we have Google, and so he introduces the Great Goddess of Teotihuacan. Newcomers to Charlie Parker need to believe, or at least believe that Charlie Parker believes. In what? The world of the ever-present dead or, put simply, ghosts. These are not cartoon spooks in white sheets, but people who have, usually, died violently. I suppose the basic presumption is that the violence of their passing somehow denies them the sleep of ages. I don’t know, but there are plenty of pages out with with more time and space to speculate than I have.

Parker’s ghost is his daughter Jennifer. Brutally murdered years ago, she is a largely benign presence, but uneasy and restless. Connolly doesn’t just skirt round the ghost issue. He takes risks, perhaps “In for a penny, in for a pound.” The ghostly Jennifer still thinks like a living person and has the same kinda of trials and tribulations experienced by her corporeal father and his friends.

As in all good crime novels, Connolly presents us with several apparently disparate plot strands, and no doubt enjoys the fact that his readers will be speculating on how they can possibly converge. As an antiques smuggler, Roland Bibas (an associate of Antonio Elizalde) is nabbed by Federal customs agents, Parker is employed by an avante-gard sculptor, Zetta Nadeau, to trace her companion, Wyatt Riggins, who has suddenly disappeared. As Parker (and his not so angelic guardians Louis and Angel) investigate the disappearance of Wyatt Riggins, they realise that they ate intruding on private grief, that being a fatal contretemps between Riggins’s boss Devin Vaughn, and a Mexican cartel jefe called Blas Urrea. Urrea has sent Seeley, one of his fixers, over the border to deal with the problem. Seeley is sinister enough, but he has a female companion who is far more terrifying than any of the cartel enforcers. Seeley’s female companion, known only as Señora, commits several more killings.

‘Murders’ isn’t quite the word, as anyone vaguely familiar with Inca methods of execution may well know. Let’s just say that a kind of open heart surgery is involved. Chillingly, Connolly describes Señora using a word I had to Google. The quote is, “There was a dryness to her tegument.” The online dictionary tells us, “the outer body covering of flatworms, including tapeworms and flukes.” The next few paragraphs are not for the faint of heart. Connolly often strays into what I call David Cronenberg territory. Here, he not so much strays as buys a plot and builds his own house.

Obviously under pressure from powerful people, Zetta unhires Parker, but her action is a red rag to a bull. Our man is nothing if not a terrier and, to mix a metaphor and quote The Bard (Conan Doyle borrowed the phrase) “The game is afoot.” Along the way, Connolly’s dialogue is tack-sharp. A long term acquaintance of Parker says,

“From what I’ve heard, you’ve been at Death’s door so often, he’s probably left a key under the mat for you.”

Quite late in the piece for a Charlie Parker novel, the exact nature of what is being smuggled north from Mexico is revealed, and it doesn’t make for comfortable reading. Old Charlie Parker hands may have become inured to some of the evils he has faced over the years, but this is something else altogether.

“I have good news and bad.”

“I’ll take the bad news first.”

“Those children Riggins stole from Mexico are already dead,” said Louis.

I felt like crawling under the sheets and never coming out again.

“And the good news?”

“They’ve been dead for a long, long time.”

This is vintage Charlie Parker, with snappy dialogue, glimpses of a darker world than the one we inhabit, and a brilliant plot. Published by Hodder & Stoughton it is out now. Anyone new to the series can click this link, and it will take to you to reviews of some of the previous novels.

Parker takes something of a back seat in this novel (which is the 20th in a magnificent series) as Louis & Angel take centre stage. The first backdrop to this stage is Amsterdam, where a criminal ‘fixer’ called De Jaager goes to an address he uses as a safe house to meet three of his colleagues. He finds one of them, a man called Paulus, shot dead, while the two women, Anouk and Liesl, have been tied up. In control of the house are two Serbian gangsters, Radovan and Spiridon Vuksan. They have come to avenge the death – in which De Jaager was complicit – of one of their acquaintances, who was nicknamed Timmerman (Timber Man) for his love of crucifying his victims on wooden beams. What follows is not for the faint of heart, but sets up a terrific revenge plot.

Parker takes something of a back seat in this novel (which is the 20th in a magnificent series) as Louis & Angel take centre stage. The first backdrop to this stage is Amsterdam, where a criminal ‘fixer’ called De Jaager goes to an address he uses as a safe house to meet three of his colleagues. He finds one of them, a man called Paulus, shot dead, while the two women, Anouk and Liesl, have been tied up. In control of the house are two Serbian gangsters, Radovan and Spiridon Vuksan. They have come to avenge the death – in which De Jaager was complicit – of one of their acquaintances, who was nicknamed Timmerman (Timber Man) for his love of crucifying his victims on wooden beams. What follows is not for the faint of heart, but sets up a terrific revenge plot.

arker is given an apology, and asked to help with the hunt for Donna Lee Kernigan’s killer. He soon learns that the Jurel Cade, a special investigator for Burden County, has been involved in the investigations – or lack thereof – into the earlier deaths. The Cade family are rich, influential and undoubtedly corrupt. They have also managed to entice Kovas, a massive defence procurement company, to build a plant in the vicinity, a deal which will put food on tables, dollars in wallets and hope in hearts for the long neglected locals. A few murdered black girls mustn’t be allowed to embarrass the PR machine that deals with the Kovas public image.

arker is given an apology, and asked to help with the hunt for Donna Lee Kernigan’s killer. He soon learns that the Jurel Cade, a special investigator for Burden County, has been involved in the investigations – or lack thereof – into the earlier deaths. The Cade family are rich, influential and undoubtedly corrupt. They have also managed to entice Kovas, a massive defence procurement company, to build a plant in the vicinity, a deal which will put food on tables, dollars in wallets and hope in hearts for the long neglected locals. A few murdered black girls mustn’t be allowed to embarrass the PR machine that deals with the Kovas public image. onnolly writes like an angel, and there is never a dead sentence, nor a misplaced word. Occasionally, within the carnage, there is a wisecrack, or a sharp line which sticks in the memory:

onnolly writes like an angel, and there is never a dead sentence, nor a misplaced word. Occasionally, within the carnage, there is a wisecrack, or a sharp line which sticks in the memory:

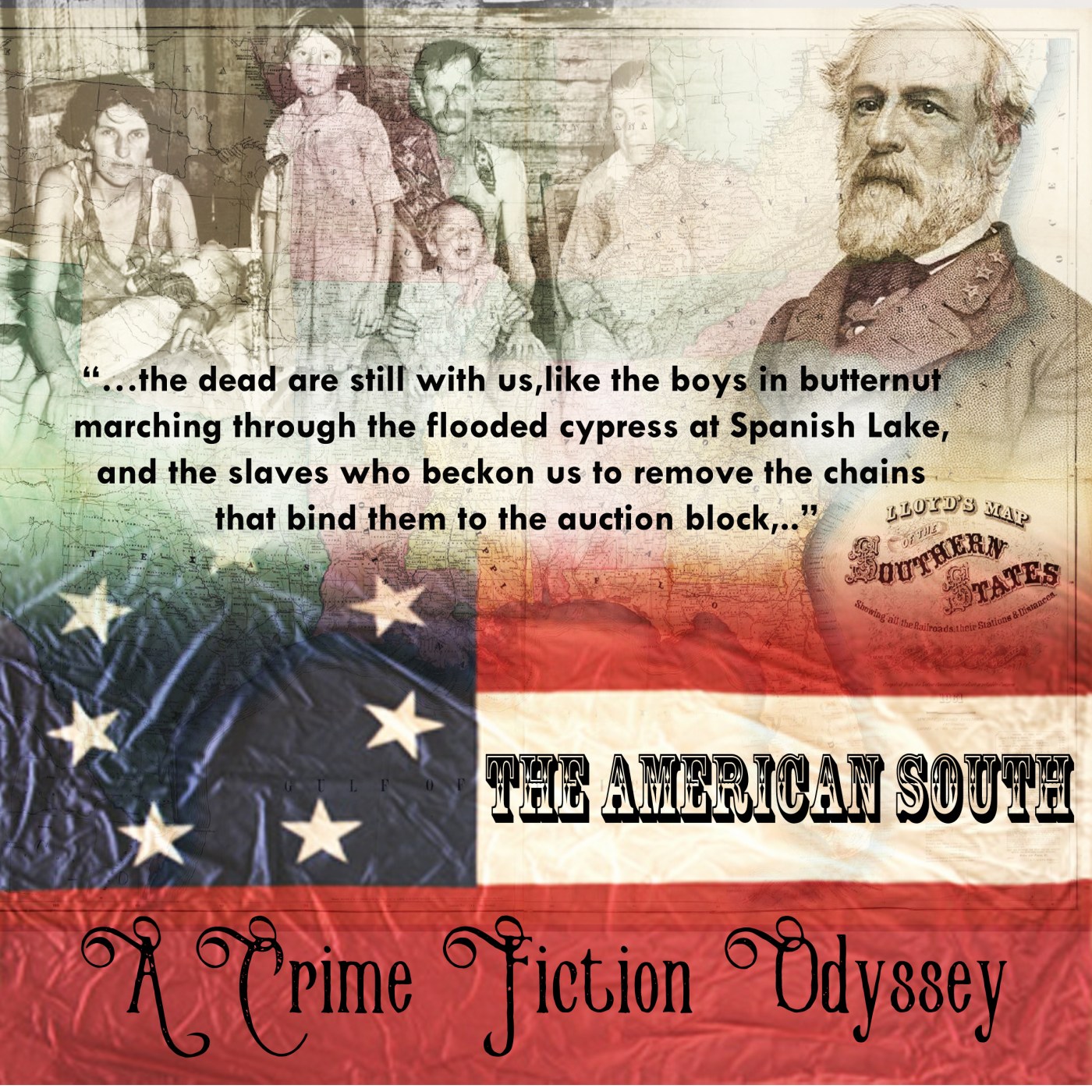

he racial element in South-set crime fiction over the last half century is peculiar in the sense that there have been few, if any, memorable black villains. There are plenty of bad black people in Walter Mosley’s novels, but then most of the characters in them are black, and they are not set in what are, for the purposes of this feature, our southern heartlands.

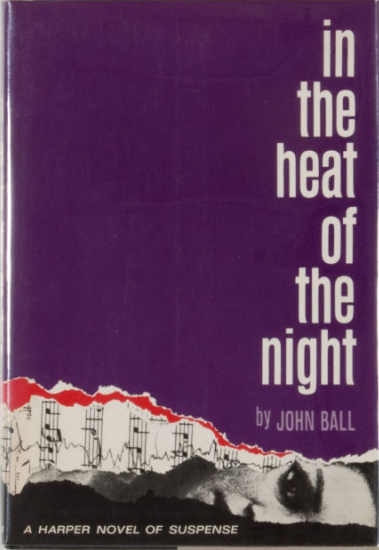

he racial element in South-set crime fiction over the last half century is peculiar in the sense that there have been few, if any, memorable black villains. There are plenty of bad black people in Walter Mosley’s novels, but then most of the characters in them are black, and they are not set in what are, for the purposes of this feature, our southern heartlands. Black characters are almost always good cops or PIs themselves, like Virgil Tibbs in John Ball’s In The Heat of The Night (1965), or they are victims of white oppression. In the latter case there is often a white person, educated and liberal in outlook, (prototype Atticus Finch, obviously) who will go to war on their behalf. Sometimes the black character is on the side of the good guys, but intimidating enough not to need help from their white associate. John Connolly’s Charlie Parker books are mostly set in the northern states, but Parker’s dangerous black buddy Louis is at his devastating best in The White Road (2002) where Parker, Louis and Angel are in South Carolina working on the case of a young black man accused of raping and killing his white girlfriend.

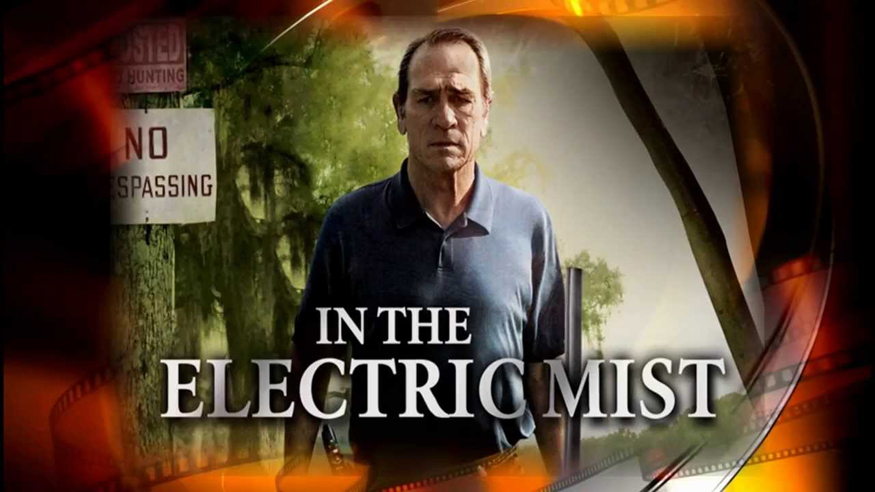

Black characters are almost always good cops or PIs themselves, like Virgil Tibbs in John Ball’s In The Heat of The Night (1965), or they are victims of white oppression. In the latter case there is often a white person, educated and liberal in outlook, (prototype Atticus Finch, obviously) who will go to war on their behalf. Sometimes the black character is on the side of the good guys, but intimidating enough not to need help from their white associate. John Connolly’s Charlie Parker books are mostly set in the northern states, but Parker’s dangerous black buddy Louis is at his devastating best in The White Road (2002) where Parker, Louis and Angel are in South Carolina working on the case of a young black man accused of raping and killing his white girlfriend. hosts, either imagined or real, are never far from Charlie Parker, but another fictional cop has more than his fair share of phantoms. James Lee Burke’s Dave Robicheaux frequently goes out to bat for black people in and around New Iberia, Louisiana. Robicheaux’s ghosts are, even when he is sober, usually that of Confederate soldiers who haunt his neighbourhood swamps and bayous. I find this an interesting slant because where John Connolly’s Louis will wreak havoc on a person who happens to have the temerity to sport a Confederate pennant on his car aerial, Robicheaux’s relationship with his CSA spectres is much more subtle.

hosts, either imagined or real, are never far from Charlie Parker, but another fictional cop has more than his fair share of phantoms. James Lee Burke’s Dave Robicheaux frequently goes out to bat for black people in and around New Iberia, Louisiana. Robicheaux’s ghosts are, even when he is sober, usually that of Confederate soldiers who haunt his neighbourhood swamps and bayous. I find this an interesting slant because where John Connolly’s Louis will wreak havoc on a person who happens to have the temerity to sport a Confederate pennant on his car aerial, Robicheaux’s relationship with his CSA spectres is much more subtle.

urke’s Louisiana is both intensely poetic and deeply political. In Robicheaux: You Know My Name he writes:

urke’s Louisiana is both intensely poetic and deeply political. In Robicheaux: You Know My Name he writes: Elsewhere his rage at his own government’s insipid reaction to the devastation of Hurricane Katrina rivals his fury at generations of white people who have bled the life and soul out of the black and Creole population of the Louisian/Texas coastal regions. Sometimes the music he hears is literal, like in Jolie Blon’s Bounce (2002), but at other times it is sombre requiem that only he can hear:

Elsewhere his rage at his own government’s insipid reaction to the devastation of Hurricane Katrina rivals his fury at generations of white people who have bled the life and soul out of the black and Creole population of the Louisian/Texas coastal regions. Sometimes the music he hears is literal, like in Jolie Blon’s Bounce (2002), but at other times it is sombre requiem that only he can hear:

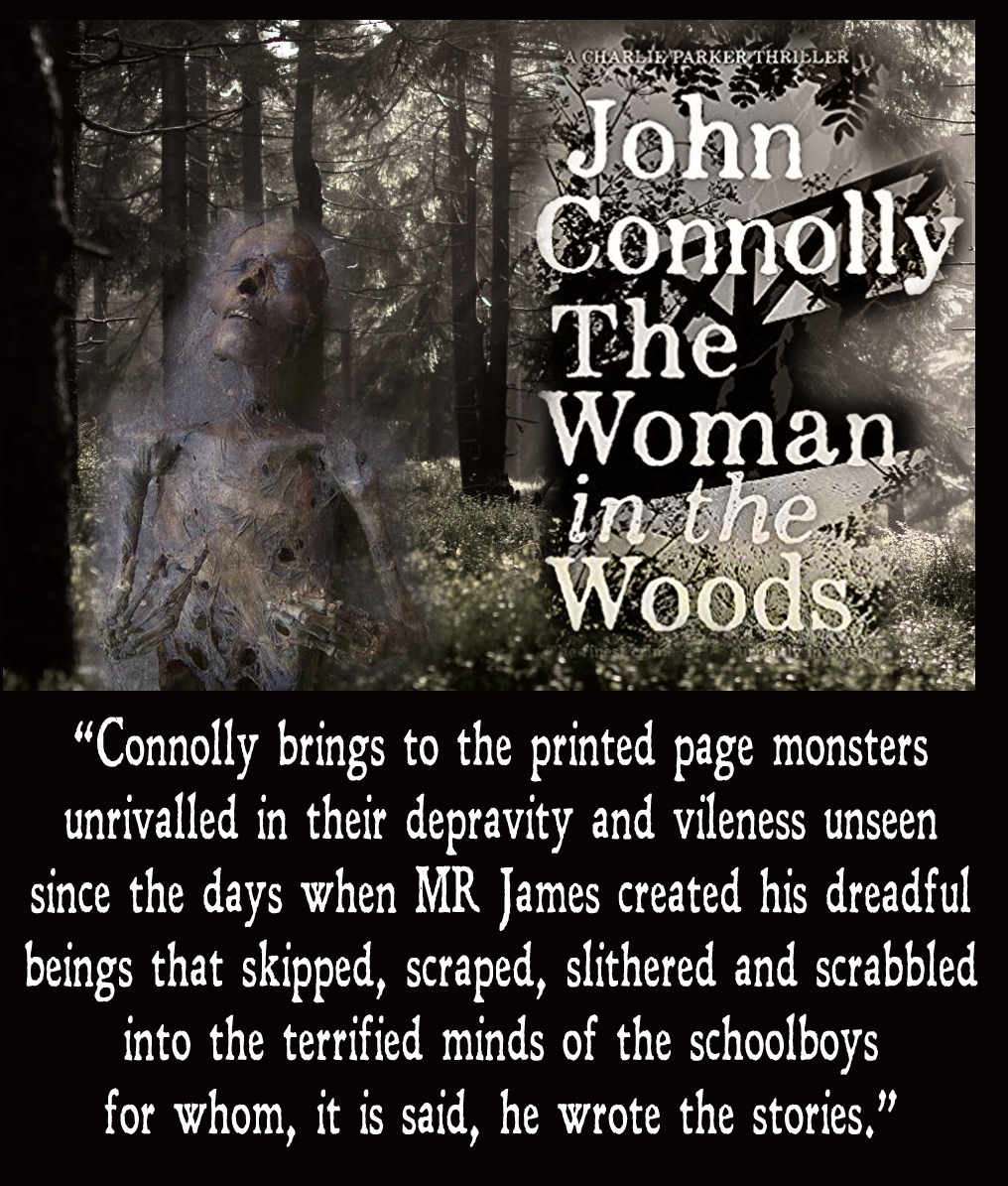

In the previous Charlie Parker novel, The Woman In The Woods, John Connolly introduced us to a frightful criminal predator, Quayle, and his malodorous and murderous familiar, Pallida Mors. Even those with the faintest acquaintance with Latin will have some understanding what her name means and, goodness gracious, does she ever live up to it! Both Quayle and Mors are seeking the final pages of a satanic book, The Fractured Atlas which, when complete, will deliver the earth – and all that is in it – to the forces of evil.

In the previous Charlie Parker novel, The Woman In The Woods, John Connolly introduced us to a frightful criminal predator, Quayle, and his malodorous and murderous familiar, Pallida Mors. Even those with the faintest acquaintance with Latin will have some understanding what her name means and, goodness gracious, does she ever live up to it! Both Quayle and Mors are seeking the final pages of a satanic book, The Fractured Atlas which, when complete, will deliver the earth – and all that is in it – to the forces of evil.

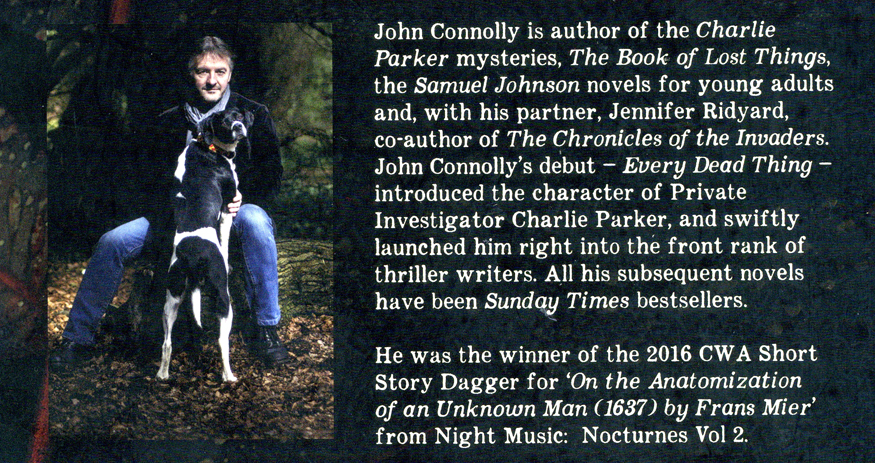

A Book of Bones is a tour de force, shot through with the grim poetry of death and suffering. Connolly (right) takes the creaky genre of horror fiction, slaps it round the face and makes it wake up, shape up and step up. He might feel that the soubriquet literary is the kiss of death for a popular novelist, but such is his scholarship, awareness of history and sensitivity that I throw the word out there in sheer admiration. Jostling each other for attention on Connolly’s stage, amid the carnage, are the unspeakably vile emissaries of evil, the petty criminals, the corrupt lawyers and the crooked cops. Charlie Parker may be haunted; you may gaze into his eyes and see a soul in ruins; his energy and motivation might be fueled by a desire to lash out at those who murdered his wife and daughter; what shines through the gloom, however, is the tiny but fiercely bright light of honesty and goodness which makes him the most memorable hero of contemporary fiction.

A Book of Bones is a tour de force, shot through with the grim poetry of death and suffering. Connolly (right) takes the creaky genre of horror fiction, slaps it round the face and makes it wake up, shape up and step up. He might feel that the soubriquet literary is the kiss of death for a popular novelist, but such is his scholarship, awareness of history and sensitivity that I throw the word out there in sheer admiration. Jostling each other for attention on Connolly’s stage, amid the carnage, are the unspeakably vile emissaries of evil, the petty criminals, the corrupt lawyers and the crooked cops. Charlie Parker may be haunted; you may gaze into his eyes and see a soul in ruins; his energy and motivation might be fueled by a desire to lash out at those who murdered his wife and daughter; what shines through the gloom, however, is the tiny but fiercely bright light of honesty and goodness which makes him the most memorable hero of contemporary fiction.

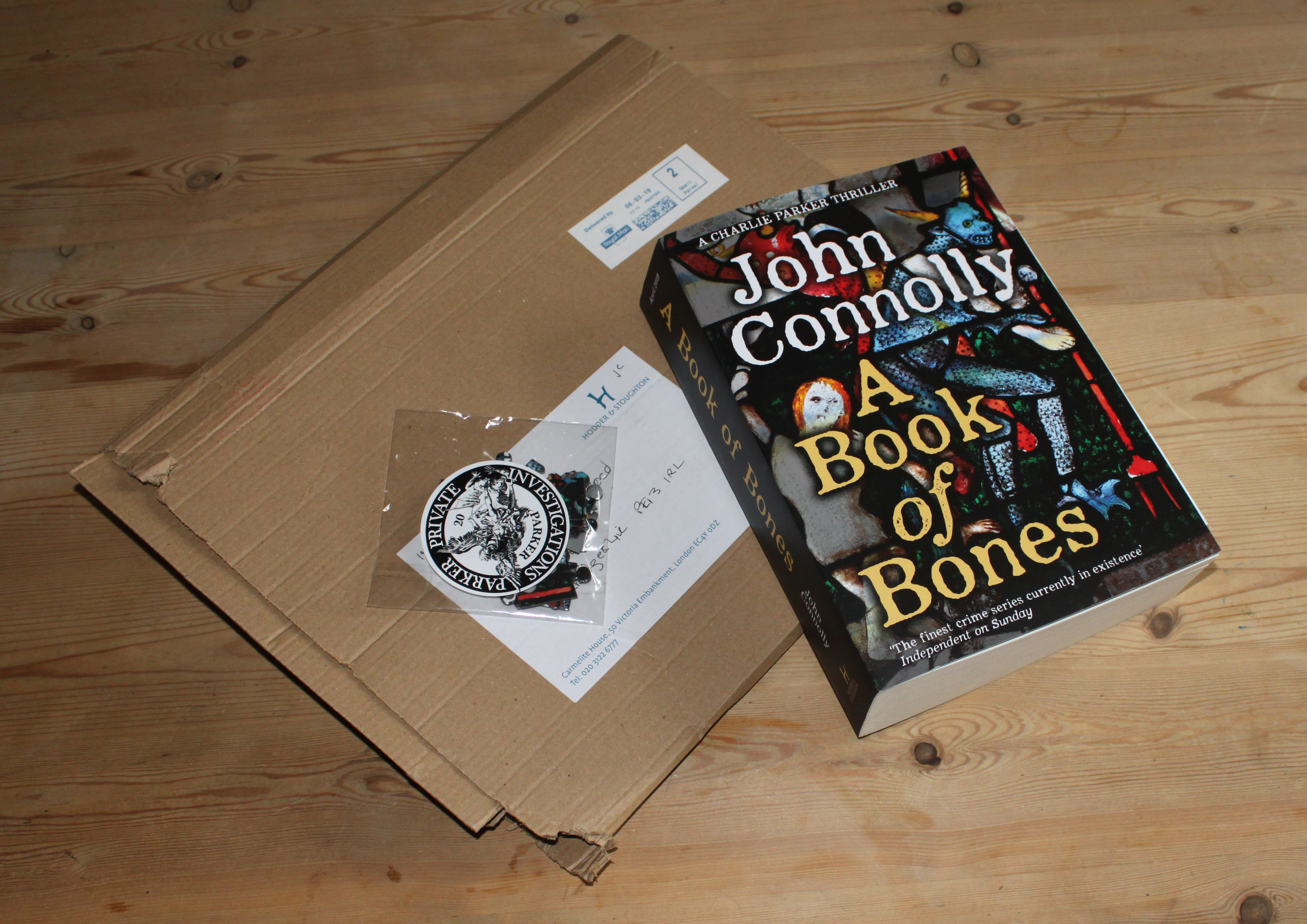

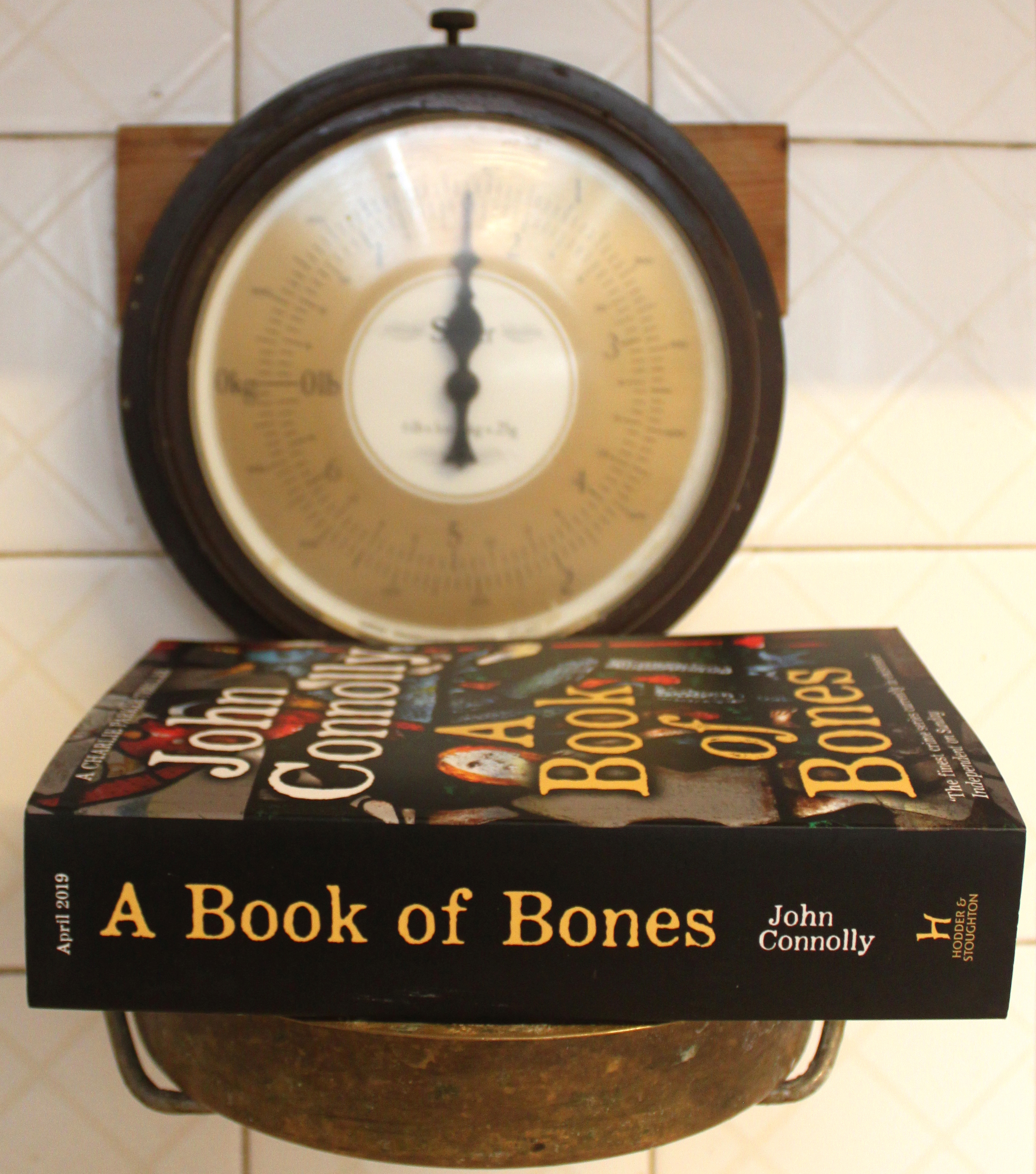

I would be lying if I said I hadn’t been counting the days until this arrived. Kerry Hood at Hodder & Stoughton is to be commended for showing great patience in the face of my impatience, but it finally arrived. Kerry had mentioned that it might be something special, but then publicists always say that, don’t they? So, ripping off the sturdy cardboard wrapper ….

I would be lying if I said I hadn’t been counting the days until this arrived. Kerry Hood at Hodder & Stoughton is to be commended for showing great patience in the face of my impatience, but it finally arrived. Kerry had mentioned that it might be something special, but then publicists always say that, don’t they? So, ripping off the sturdy cardboard wrapper ….

Ta-da! And there it was, the long awaited latest journey into the darkness of men and angels for the Maine PI, Charlie Parker. The adjectives are easy – haunted, conflicted, convincing, troubled, angry, brave … fans of the series can play their own ‘describe Charlie Parker’ game, but most importantly, our man is back.

Ta-da! And there it was, the long awaited latest journey into the darkness of men and angels for the Maine PI, Charlie Parker. The adjectives are easy – haunted, conflicted, convincing, troubled, angry, brave … fans of the series can play their own ‘describe Charlie Parker’ game, but most importantly, our man is back.

Charlie Parker is back, and how! I was advised that I might want to set aside a fair amount of time to read A Book of Bones but, blimey, Kerry was not wrong. At a little short of 700 pages, and weighing nearly 2lbs in old money, the book is certainly a big ‘un. New readers shouldn’t be daunted, though. John Connolly couldn’t write a dull sentence even if he went off to his Alma Mater, Trinity College Dublin, to do a doctorate in dullness.

Charlie Parker is back, and how! I was advised that I might want to set aside a fair amount of time to read A Book of Bones but, blimey, Kerry was not wrong. At a little short of 700 pages, and weighing nearly 2lbs in old money, the book is certainly a big ‘un. New readers shouldn’t be daunted, though. John Connolly couldn’t write a dull sentence even if he went off to his Alma Mater, Trinity College Dublin, to do a doctorate in dullness.

But there was more! Book publicists are an inventive lot, and over the years I’ve had packets of sweets, tiny vials of perfume, books wrapped in funereal paper and black ribbon, facsimiles of detective case files – but never a jigsaw. Wrapped up in a cellophane packet with a lovely Charlie Parker 20 year anniversary graphic were the pieces.

But there was more! Book publicists are an inventive lot, and over the years I’ve had packets of sweets, tiny vials of perfume, books wrapped in funereal paper and black ribbon, facsimiles of detective case files – but never a jigsaw. Wrapped up in a cellophane packet with a lovely Charlie Parker 20 year anniversary graphic were the pieces.

As I was always told to do by my old mum, I isolated the bits with the straight edges first. There was clearly a written message in there, set against the lovely – but sinister – stained glass background. Confession time; although the puzzle didn’t have too many pieces, I got stuck. Fortunately, Mrs P was taking a very rare day off work with a flu bug, and as she is a jigsaw ace, she finished it off for me.

As I was always told to do by my old mum, I isolated the bits with the straight edges first. There was clearly a written message in there, set against the lovely – but sinister – stained glass background. Confession time; although the puzzle didn’t have too many pieces, I got stuck. Fortunately, Mrs P was taking a very rare day off work with a flu bug, and as she is a jigsaw ace, she finished it off for me.

In the dark woods of Maine a tree gives up the ghost and topples to the ground. As its roots spring free of the cold earth a makeshift tomb is revealed. The occupant was a young woman. When the girl – for she was little more than that – is discovered, the police and the medical services enact their time-honoured rituals and discover that she died of natural causes not long after giving birth. But where is the child she bore? And why was a Star of David carved on the trunk of an adjacent tree? Portland lawyer Moxie Castin is not a particularly devout Jew, but he fears that the ancient symbol may signify something damaging, and he hires PI Charlie Parker to shadow the police enquiry and investigate the carving – and the melancholy discovery beneath it.

In the dark woods of Maine a tree gives up the ghost and topples to the ground. As its roots spring free of the cold earth a makeshift tomb is revealed. The occupant was a young woman. When the girl – for she was little more than that – is discovered, the police and the medical services enact their time-honoured rituals and discover that she died of natural causes not long after giving birth. But where is the child she bore? And why was a Star of David carved on the trunk of an adjacent tree? Portland lawyer Moxie Castin is not a particularly devout Jew, but he fears that the ancient symbol may signify something damaging, and he hires PI Charlie Parker to shadow the police enquiry and investigate the carving – and the melancholy discovery beneath it. In another life John Connolly would have been a poet. His prose is sonorous and powerful, and his insights into the world of Charie Parker – both the everyday things he sees with his waking eyes and the dark landscape of his dreams – are vivid and sometimes painful. Connolly’s villains – and there have been many during the course of the Charlie Parker series – are not just bad guys. They do dreadful things, certainly, but they even smell of the decaying depths of hell, and they often have powers that even a gunshot to the head from a .38 Special can hardly dent.

In another life John Connolly would have been a poet. His prose is sonorous and powerful, and his insights into the world of Charie Parker – both the everyday things he sees with his waking eyes and the dark landscape of his dreams – are vivid and sometimes painful. Connolly’s villains – and there have been many during the course of the Charlie Parker series – are not just bad guys. They do dreadful things, certainly, but they even smell of the decaying depths of hell, and they often have powers that even a gunshot to the head from a .38 Special can hardly dent.