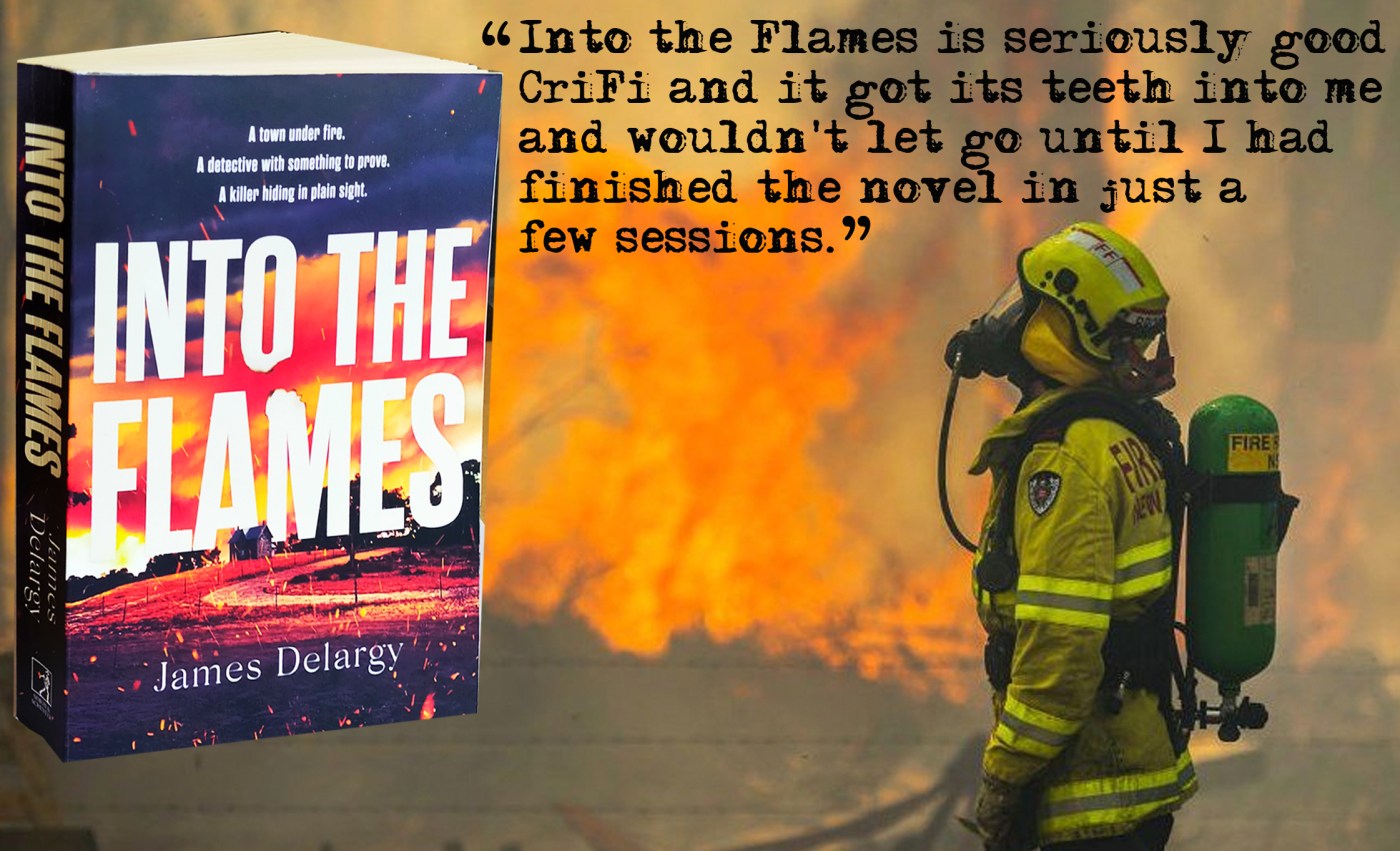

I lived and worked in Australia for a while, but being a city lad, I never came close to a bush fire. From speaking to people who had, and reading about them, they seem to be the very worst kind of natural disaster. Perhaps it is invidious to compare tornadoes, tsunamis, landslips and volcanlc eruptions, but bush fires seem to have an almost animal intensity. They devour people, buildings and forests like some kind of raging beast. Here, Aussie cop Alex Kennard has been bounced out of his job in a Sydney suburb for, as his bosses saw it, making the wrong call when he was forced to deal with a hostage situation. He is now more or less twiddling his thumbs dealing with drunks, petty thieving and the odd traffic incident in the town of Katoomba, in the heart of The Blue Mountains.

The little nearby town of Rislake is threatened by a serious bush fire, and Kennard drives across to help with crowd management in the event of a major evacuation. The local cops and fire service are basically taking a roll call, and it is soon apparent that one woman is missing. Tracey Hilmeyer is the wife of one of the firefighters and, against orders, Kennard and the woman’s husband, Russell, head out to the Hilmeyer property which is in danger of being engulfed. They find Tracey, but she is dead at the foot of the stairs, battered with a heavy implement. Russell Hilmeyer is distraught and wants to move the body of his wife, but Kennard insists that she stay in place and he attempts to preserve and record the crime scene as best he can.

Russell Hilmeyer is a local lad who didn’t quite make the big time on the football field, due to a career-ending injury. It has no bearing on the plot, but I am pretty sure Hilmeyer played Aussie Rules rather than what Americans call Soccer, or the major Sydney code of Rugby League. His wife Tracey was a glamorous prom-queen type in her teens, and had ambitions to be an artist. The gallery she ran in town has had to close, and she had become depressed, and only got through her days and nights with the help of prescription items like co-codomol. She had an abrasive relationship with her sister Karen who, with her husband, runs the farm that used to belong to their late parents. It is hard scrabble land, and they barely make ends meet. Did Karen and her Pacific Islander husband Alvin hate Tracey enough to kill her? The post mortem reveals that Tracey Hilmeyer was pregnant. Given that the couple had been trying for years to have children, does this add yet another dimension to the search for the killer and their possible motive?

The author has great fun making Kennard and his temporary partner DS Layton jump to one false assumption after another, while the fire grows steadily worse, a little like Satan as described in the office of Compline:

“Be sober, be vigilant, because your adversary the devil, as a roaring lion, walketh about, seeking whom he may devour:”

The conclusion comes with Layton temporarily out of action due to the fire having triggered her asthma, and we have Kennard, almost immobilised by the weight of his protective clothing, pursuing the killer in a Dante’s Inferno of blazing eucalyptus trees and showering sparks. Only one small problem. The person he is following isn’t the killer of Tracey Hilmayer. To say any more would clearly spoil your fun, but this is as exciting an end to a crime novel as I have read in many moons.

We lost the two modern giants of Australian crime fiction, the two Peters – Corris and Temple – within six months of each other in 2018 but, along with Jane Harper, James Delargy – although he now lives in England – taps into to the great tradition established by those writers. Into the Flames is seriously good CriFi and it got its teeth into me and wouldn’t let go until I had finished the novel in just a few sessions. Published by Simon and Schuster, it is available now.

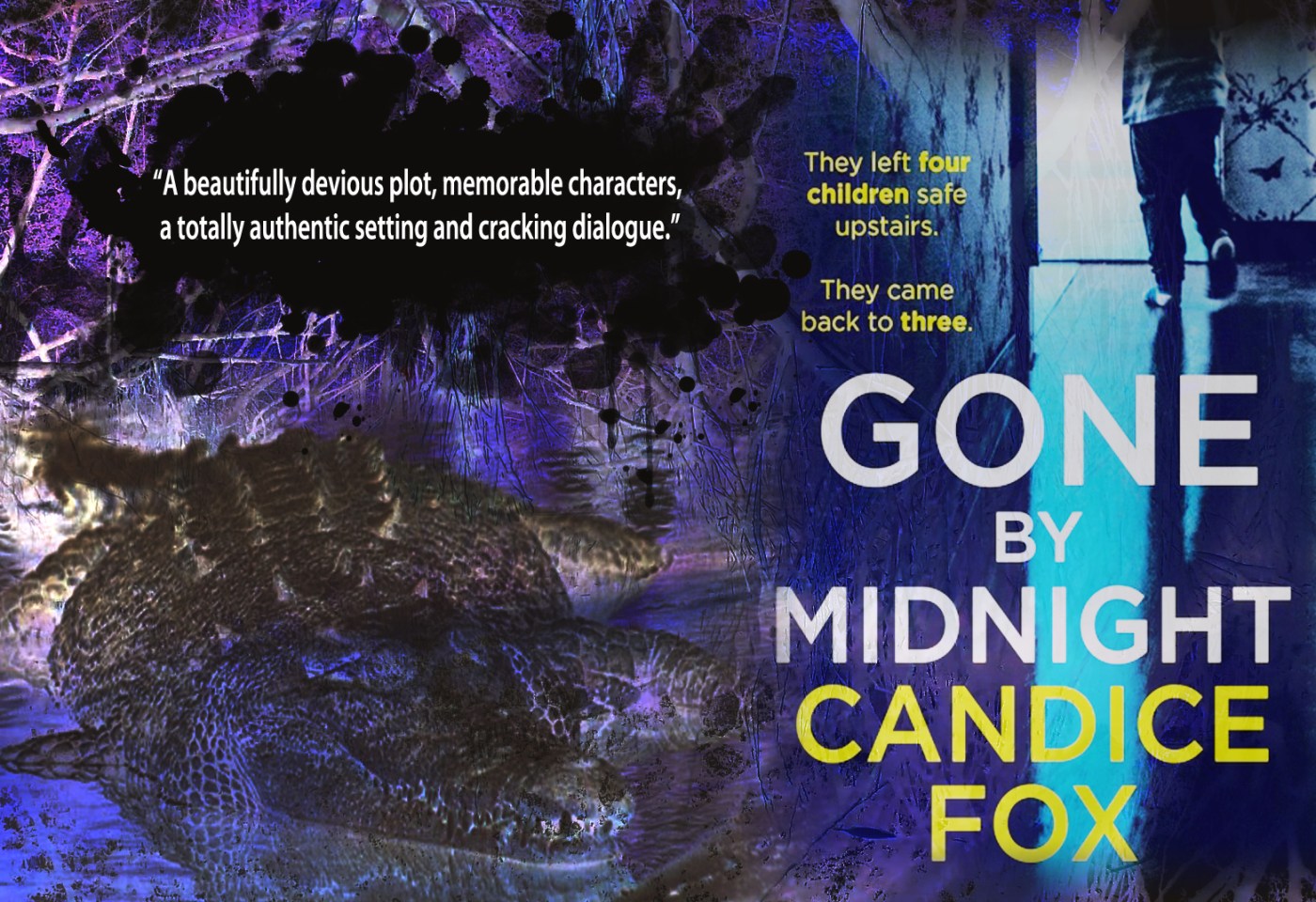

Australian crime fiction suffered two body blows in 2018 when the two great Peters – Temple and Corris – died within months of each other. While they can never be replaced, there is, thankfully, a younger generation stepping up to the plate, and Candice Fox (left) is in the first rank of these. No-one needs to be reminded of the great detective duos of the past, but Fox has created a partnership for the 21st century in the persons of Ted Conkaffey and Amanda Pharrell.

Australian crime fiction suffered two body blows in 2018 when the two great Peters – Temple and Corris – died within months of each other. While they can never be replaced, there is, thankfully, a younger generation stepping up to the plate, and Candice Fox (left) is in the first rank of these. No-one needs to be reminded of the great detective duos of the past, but Fox has created a partnership for the 21st century in the persons of Ted Conkaffey and Amanda Pharrell. Richie Farrell’s disappearance is less of a conundrum than a downright impossibility. There is no obvious motive, no forensic evidence, and no sign of him – or his abductor – on the plentiful CCTV footage in and around the hotel. When the solution does come, it is extremely ingenious, and owes its surprising nature to the characters in the story – and us readers – making the kinds of assumptions that the great consulting detective of 221B Baker Street was so good at avoiding.

Richie Farrell’s disappearance is less of a conundrum than a downright impossibility. There is no obvious motive, no forensic evidence, and no sign of him – or his abductor – on the plentiful CCTV footage in and around the hotel. When the solution does come, it is extremely ingenious, and owes its surprising nature to the characters in the story – and us readers – making the kinds of assumptions that the great consulting detective of 221B Baker Street was so good at avoiding.

The town of Kiewarra is a dusty five hour drive from Melbourne. Five hours. Six, maybe, if you weren’t that anxious to get there. Five hours, under the same relentless sun, but it might as well be fifty, for all the similarity there is. Melbourne, with its prosperity, its glass and steel central business district, its internationally renowned restaurants and its louche air as a cosmopolitan city. Kiewarra. A pub, a couple of bottle shops and a milk bar; a run-down school, starved of funds; a farming economy choked and parched by two years without rain; families turned bitter and taciturn by the shared misery of failed crops and burgeoning overdrafts. Author Jane Harper (left) takes us right into the deep dark blue centre of this community.

The town of Kiewarra is a dusty five hour drive from Melbourne. Five hours. Six, maybe, if you weren’t that anxious to get there. Five hours, under the same relentless sun, but it might as well be fifty, for all the similarity there is. Melbourne, with its prosperity, its glass and steel central business district, its internationally renowned restaurants and its louche air as a cosmopolitan city. Kiewarra. A pub, a couple of bottle shops and a milk bar; a run-down school, starved of funds; a farming economy choked and parched by two years without rain; families turned bitter and taciturn by the shared misery of failed crops and burgeoning overdrafts. Author Jane Harper (left) takes us right into the deep dark blue centre of this community. Seeing the coffin of a contemporary being carried through the church is bad enough for Falk, but when it is followed by two smaller ones, one being very much smaller, that is a different thing altogether. For the other two coffins are occupied by Hadler’s wife Karen, and his young son Billy. The story has played out across the mainstream media as a suicide-killing. Luke Hadler, driven mad by debt, failure, jealousy, despair – who knows? – has shot dead his wife and son, and then turned the gun on himself, albeit leaving his thirteen month old daughter Charlotte in her cot, screaming, terrified, but very much alive.

Seeing the coffin of a contemporary being carried through the church is bad enough for Falk, but when it is followed by two smaller ones, one being very much smaller, that is a different thing altogether. For the other two coffins are occupied by Hadler’s wife Karen, and his young son Billy. The story has played out across the mainstream media as a suicide-killing. Luke Hadler, driven mad by debt, failure, jealousy, despair – who knows? – has shot dead his wife and son, and then turned the gun on himself, albeit leaving his thirteen month old daughter Charlotte in her cot, screaming, terrified, but very much alive.

Murder In Mt Martha is one such book. For those who have never visited Melbourne, Mount Martha is a town on the Mornington Peninsula, best known as what we Brits would call a seaside town. The ‘Mount’ is a shade over 500 ft, and is named after the wife of one of the early settlers. Author Janice Simpson (left) has taken a real-life unsolved murder from the 1950s as one thread, and created another involving a present day post-grad student who is interviewing an old man about his early life in the post-war Victorian city. Simpson has woven the two threads together to create a fabric that shimmers, shocks and surprises.

Murder In Mt Martha is one such book. For those who have never visited Melbourne, Mount Martha is a town on the Mornington Peninsula, best known as what we Brits would call a seaside town. The ‘Mount’ is a shade over 500 ft, and is named after the wife of one of the early settlers. Author Janice Simpson (left) has taken a real-life unsolved murder from the 1950s as one thread, and created another involving a present day post-grad student who is interviewing an old man about his early life in the post-war Victorian city. Simpson has woven the two threads together to create a fabric that shimmers, shocks and surprises. Simpson keeps Szabo blissfully unaware that Arthur Boyle is a relative of Ern Kavanagh. Arthur only recalls him in fits and starts, believing that he was his uncle, but Simpson lets us into the secret as she describes Ern’s life over half a century earlier. The book opens with a graphic description of the brutal murder of an innocent teenager whose parents have reluctantly allowed her to travel alone to her first party. There is never any doubt in our minds that Ern Kavanagh killed the girl, but we are kept on a knife-edge of not knowing if he will get away with the murder.

Simpson keeps Szabo blissfully unaware that Arthur Boyle is a relative of Ern Kavanagh. Arthur only recalls him in fits and starts, believing that he was his uncle, but Simpson lets us into the secret as she describes Ern’s life over half a century earlier. The book opens with a graphic description of the brutal murder of an innocent teenager whose parents have reluctantly allowed her to travel alone to her first party. There is never any doubt in our minds that Ern Kavanagh killed the girl, but we are kept on a knife-edge of not knowing if he will get away with the murder.

AUSTRALIAN CRIME FICTION doesn’t come my way anywhere near as much as I would like. I’m a massive fan of Peter Temple, but new books from him are as rare as hens’ teeth. For snappy, PI-style reads, there’s always Peter Corris and his Cliff Hardy novels. So, it was with great pleasure that I opened the packet from Little, Brown publishers, to find that I was holding a brand spanking new Australian crime story.

AUSTRALIAN CRIME FICTION doesn’t come my way anywhere near as much as I would like. I’m a massive fan of Peter Temple, but new books from him are as rare as hens’ teeth. For snappy, PI-style reads, there’s always Peter Corris and his Cliff Hardy novels. So, it was with great pleasure that I opened the packet from Little, Brown publishers, to find that I was holding a brand spanking new Australian crime story.