Susan Coates was born in November 1853 in the village of New Bolingbroke. At the age of 18, she gave birth to a son – to be called Henry Coates-Harrison. The double-barreled surname was not a sign of nobility, but rather that the boy’s father was a local farmer called Edward Harrison. Three years later, the couple “did the decent thing” and married on 19th October 1874, in the church of St Andrew, Miningsby. I imagine that it must have been a Victorian church, as it was declared redundant and demolished in 1975. A medieval building would not have suffered that fate.

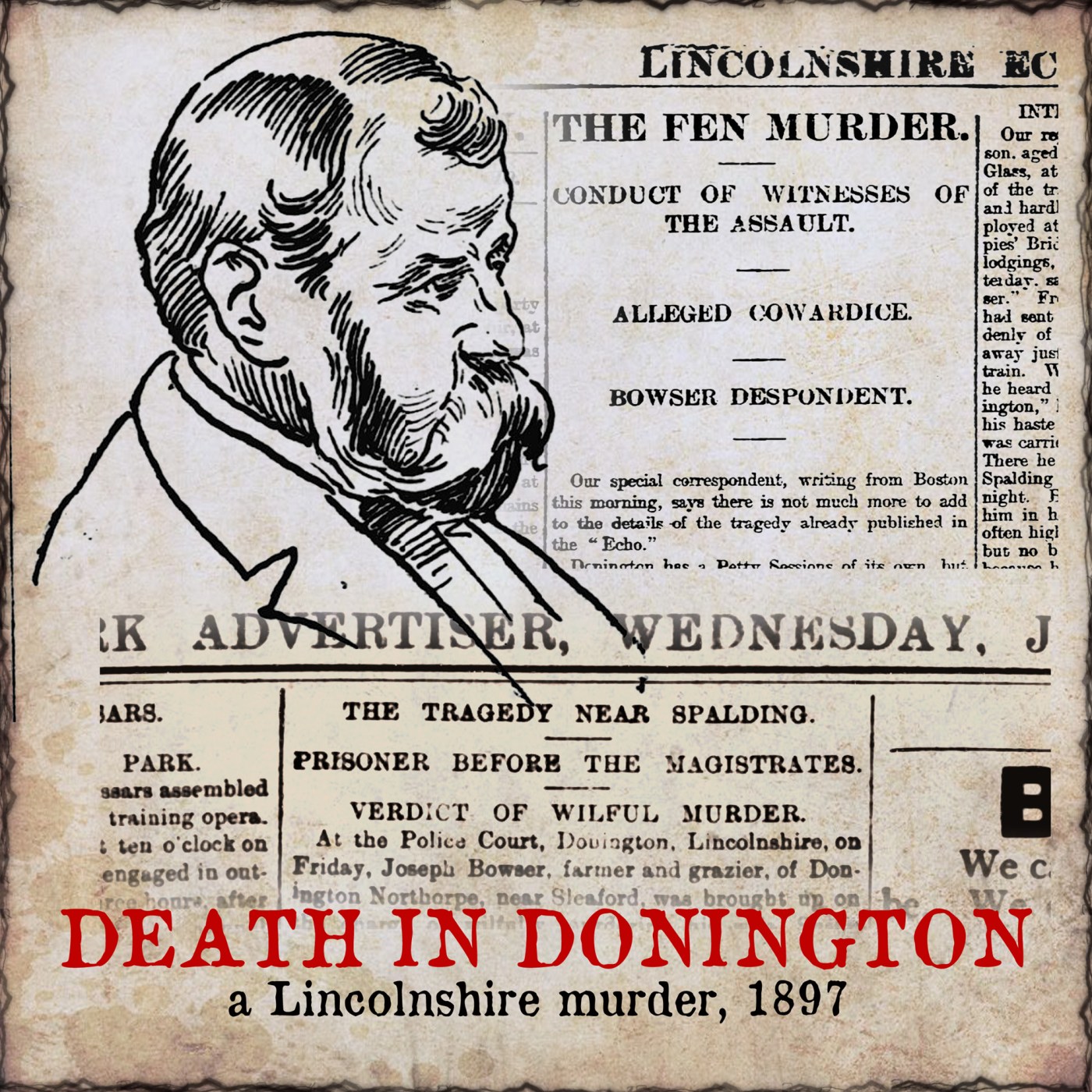

The 1881 census has the three of them plus Edward’s elderly father – living in what the document describes as ‘Enderby Allot”. Short for allotment, possibly? No matter. Edward Harrison did not live to complete the next census, as he died in 1884. The farm did not pass on to Susan, which suggests that they were tenants. It seems that in widowhood she took up a position as housekeeper to another local farmer, Joseph Bowser. She married him in December 1886. Bowser’s history has been difficult to pin down, for one or two reasons. The first is that when the census records were digitised, his name was misread as “Beezer”, which accounts for his near invisibility. Secondly, there is another Joseph Bowser, also a farmer, and also living in the area, but he seems to be a much younger man than “our” Joseph, who was born in 1854, in Sibsey. The 1891 census has him living in Northorpe, a hamlet just north of Donington, and his wife is named as Susanah. He was something of a local dignitary, and was on the *Board of Guardians in Spalding.

*The 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act put an end to out relief, grouping parishes together into legislative bodies called Poor Law Unions. Each was administered by a board of guardians who would oversee the running of a workhouse.

Bowser was however, a volatile sort of man, as a newspaper later describes.

“Bowser was a familiar figure market days, and every regular attendant knew him. Many are the stories that are being retailed in illustration of his excitable nature and violent temper. The general opinion would appear be that he was the worse for drink at the time, and was a common thing for him to indulge freely before he left Boston on market days, when he would drive away at break-neck speed down West-street and to Sleaford-road. The use of a gun as argument appears have been a favourite one with Bowser, as it is stated he on one occasion shot a valuable horse that was rather lively in the field, and which he could not capture, and another time a greyhound did not readily obey his commands, and its career was put an end to in equally summary and untimely manner.”

Despite much searching for clues, I have been unable to identify for certain which of Northorpe’s farms was run by Bowser. I do know that he was a tenant of the principal local landowner, Captain Richard Gleed, of Park House. My best guess is that it was one of the farms near Hammond Beck Bridge.

By 1897, the relationship between Joseph Bowser and his wife has seriously deteriorated. Susan’s son, now 26 had left and was living in Lincoln, and Bowser’s behaviour was frequently affected by drink. The Lincolnshire Echo of Thursday 27th May reported:

“His wife had left him for short time on several occasions owing to his treatment, and had often sought refuge the house of Mrs. Roe*, at the lane end, but Bowser would go there and smash the windows, Mrs. Rowe after a time dare not shelter her.”

*The Roe family are listed next to the Bowsers on the 1891 census return, in the vicinity of Hammond Beck Bridge.

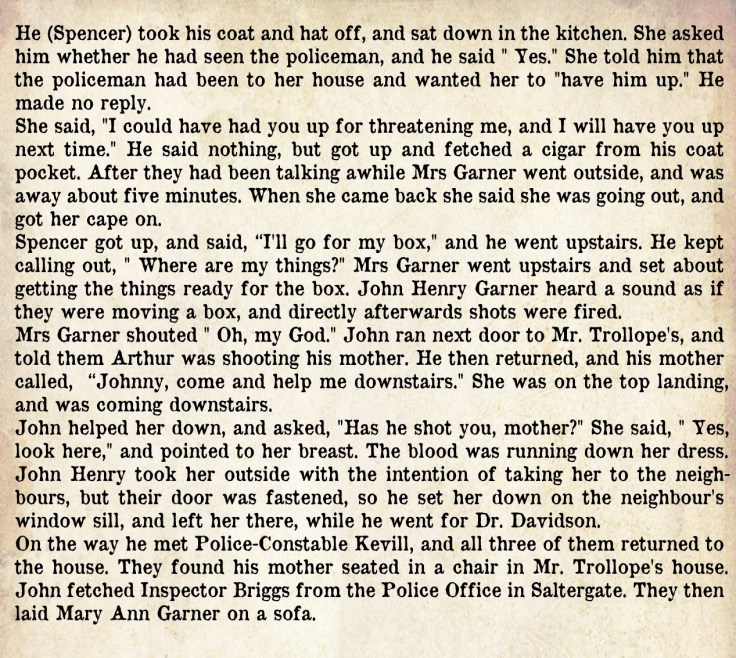

Whatever the demons were that drove him to seek comfort in the bottle, they were particularly vindictive on Tuesday 25th May, 1897. He had risen at the usual time, but thought better of it, and returned to his bed with a bottle of whisky. Later on in the afternoon, in the grip of drink, he staggered from his bed and went downstairs. A newspaper reported what happened next:

“Towards evening, the only people in the house at the time were Bowser and his wife and a servant girl named Berridge. Two visitors were staying at the place – a Mr. Lister, of Mavis Enderby, near Spilsby, aud Miss Barber of Wyberton – but they had gone out for a walk when the quarrel commenced. From a statement by the servant girl, it appears that Mrs. Bowser had been engaged with her domestic duties more or less during the day. In the afternoon, according to custom, she was preparing some chicken food, and about this time Bowser left the house, and coming up to his wife, said,

“What are you mixing that for?“ and she said

“For the chickens.”

Bowser then began call his wife names and otherwise insult her, but she took no notice, and walked round to the front the house. Bowser, however, followed her into the home held, where he kicked her, and she fell to the ground. He again kicked her while in this position. It was clear that Mrs. Bowser was hurt, for she failed to rise. In the meantime her husband had returned to the house. Mrs. Bowser length got up, and walked with difficulty to the calf-house where she supported herself near the door.”

IN PART TWO

GUNSHOTS

A FUNERAL

A TRIAL

A DATE WITH MR BILLINGTON

In far-off Norfolk, men repairing flood defences near Denver Sluice have discovered what appears to be the remains of a child inside the rotted skeleton of a boat. Hunt, accompanied by Colonel Michael Field, a grizzled veteran of Cromwell’s army, and Hooke’s niece, Grace. When the trio arrive in Norfolk, Hunt soon determines that the remains are not those of a child, but the mortal remains of Jeffrey Hudson, who was known as the Queen’s Dwarf – the Queen in question being the late Henrietta Maria (left), wife of Charles I. The situation becomes more bizarre when Hunt learns that Hudson is not dead, but living in the town of Oakham, 60 miles west across the Fens. Hunt and his companions’ journey only delivers up more mystery when they find that ‘Jeffrey Hudson’ has left the town. Hunt knows that the jolly boat* which contained the skeleton belonged to a French trader, Incasble, which worked out of King’s Lynn.

In far-off Norfolk, men repairing flood defences near Denver Sluice have discovered what appears to be the remains of a child inside the rotted skeleton of a boat. Hunt, accompanied by Colonel Michael Field, a grizzled veteran of Cromwell’s army, and Hooke’s niece, Grace. When the trio arrive in Norfolk, Hunt soon determines that the remains are not those of a child, but the mortal remains of Jeffrey Hudson, who was known as the Queen’s Dwarf – the Queen in question being the late Henrietta Maria (left), wife of Charles I. The situation becomes more bizarre when Hunt learns that Hudson is not dead, but living in the town of Oakham, 60 miles west across the Fens. Hunt and his companions’ journey only delivers up more mystery when they find that ‘Jeffrey Hudson’ has left the town. Hunt knows that the jolly boat* which contained the skeleton belonged to a French trader, Incasble, which worked out of King’s Lynn. Hunt’s odyssey continues. In King’s Lynn, Hunt and his companions are summoned to the presence of the Duchesse de Mazarin. Hortense Mancini is one of the most beautiful women in Europe. She is highly connected, but also notorious as one of Charles II’s (several) mistresses. She reveals that the mysterious dwarf – or his impersonator – may be in possession of a a legendary gemstone – the Sancy – a diamond of legendary worth, and the cause of centuries of intrigue and villainy. The Duchesse bids Harry to travel to Paris, but once there, his fortunes take a turn for the worse.

Hunt’s odyssey continues. In King’s Lynn, Hunt and his companions are summoned to the presence of the Duchesse de Mazarin. Hortense Mancini is one of the most beautiful women in Europe. She is highly connected, but also notorious as one of Charles II’s (several) mistresses. She reveals that the mysterious dwarf – or his impersonator – may be in possession of a a legendary gemstone – the Sancy – a diamond of legendary worth, and the cause of centuries of intrigue and villainy. The Duchesse bids Harry to travel to Paris, but once there, his fortunes take a turn for the worse.

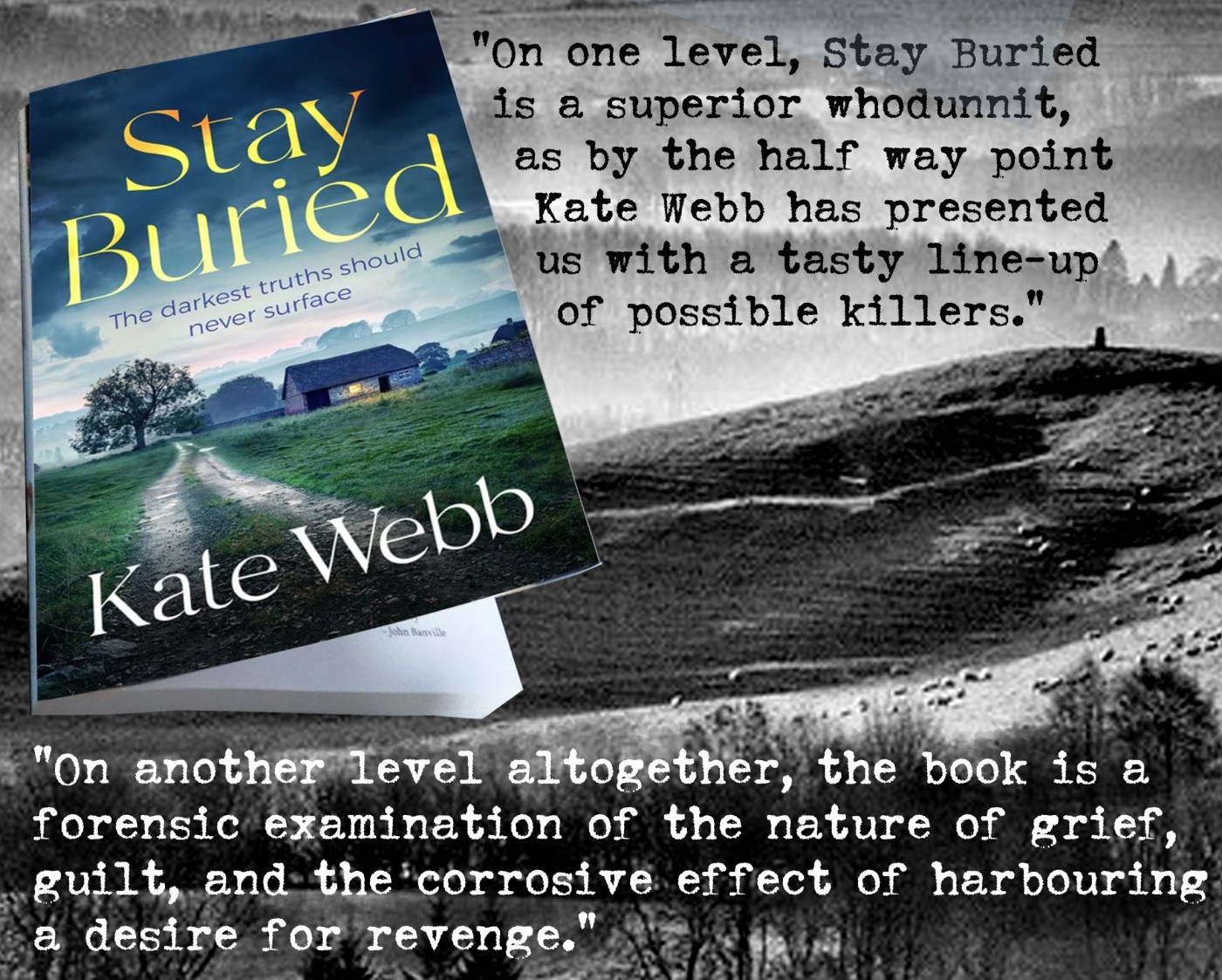

Writing as Katherine Webb, the author (left) is a well established writer of several books which seem to be in the romantic/historical/mystery genre, but I believe this is her first novel with both feet firmly planted on the terra firma of crime fiction. Wiltshire copper DI Matthew Lockyer, after a professional error of judgment, has been sidelined into a Cold Case unit, consisting of himself and Constable Gemma Broad.

Writing as Katherine Webb, the author (left) is a well established writer of several books which seem to be in the romantic/historical/mystery genre, but I believe this is her first novel with both feet firmly planted on the terra firma of crime fiction. Wiltshire copper DI Matthew Lockyer, after a professional error of judgment, has been sidelined into a Cold Case unit, consisting of himself and Constable Gemma Broad.