These days when Fenland fruit needs picking, the hands that do the work will belong to people who come from places like Vilnius. Klaipeda, Varna, Daugavpils, or Bucharest. Back in the day, however,the pickers came from less exotic places like Hackney, Hoxton or Haringey, and the temporary migration of Londoners to the Wisbech area was an established part of the early summer season. In the autumn, the same people – predominantly women and children, might head south to the hop fields of Kent, but in the July of 1912 the Londoners were here in Fenland.

These days when Fenland fruit needs picking, the hands that do the work will belong to people who come from places like Vilnius. Klaipeda, Varna, Daugavpils, or Bucharest. Back in the day, however,the pickers came from less exotic places like Hackney, Hoxton or Haringey, and the temporary migration of Londoners to the Wisbech area was an established part of the early summer season. In the autumn, the same people – predominantly women and children, might head south to the hop fields of Kent, but in the July of 1912 the Londoners were here in Fenland.

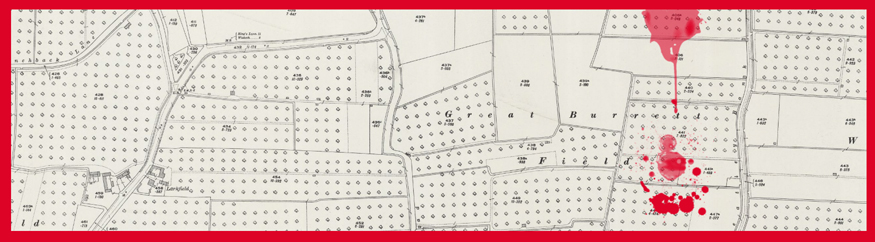

One of the farms in the area which welcomed the London visitors was that of John Stanton Batterham, of Larkfield, Lynn Road, Walsoken. His house still stands:

He was to play no direct part in the tragedy that unfolded on the afternoon of 16th July, 1912, but some of the people who worked for him – and two in particular – were key players.

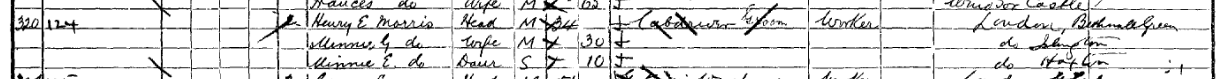

Minnie Morris has been hard to trace using public records. Her mother, Minnie Gertrude Morris had married (a re-marriage) John M Stringfield in the autumn of 1911, but the 1901 census has her living with a Henry Morris (who was almost twice her age) in Grays Inn Buildings, Roseberry Avenue, Holborn. Also listed is a daughter, also called Minnie, born in Hoxton in 1891.

Minnie junior is hard to locate in 1911, but on the other side of town, in North Kensington, a young man named Robert Galloway was living with his large family in Angola Mews:

To call Robert and Minnie “star-crossed lovers” is probably pushing the Shakespeare analogy a step too far, but their paths crossed in the summer of 1912. Both turned up, from different parts of the country, to pick fruit for Mr Batterham. It seems that the hours were flexible, and there was money to be handed over the bar in The Black Bear, and the Bell Inn. The Black Bear still thrives, despite the curse of lock-down, but the Bell Inn is long gone. (below)

William Tucker, labourer, Old Walsoken, said he came from London in May last for fruit-picking. He knew Minnie Morris for a few months, and he met her in London. He saw her in the Bell Inn Walsoken, in June. He used to meet her about four times a week and was fond of her. He used to give her grub and spend evenings with her.”

Galloway was described as a seaman in contemporary reports, but there is no evidence to support this. Perhaps the term suggested something exotic and dangerous, and journalists at the time would be as aware of ‘clickbait’ as we are today, even though they might have used a different term. He was clearly violently jealous, and anyone paying court to Minnie Morris was regarded as a mortal enemy.

On 11th July there was a clashing of heads in the Black Bear inn.

Galloway saw William Tucker and Minnie Morris drinking together in the Black Bear inn. Galloway said: “Minnie. I want to speak to you.“

She replied: “I’m all right where I am.”

Tucker and Minnie Morris then went out of the inn and stood talking. Galloway said the girl:

“If I don’t find you I’ll find him”, meaning William Tucker.

Over a century later, it is hard to come to any other conclusion other than that Robert Galloway was obsessed with Minnie Morris, and his feelings were that if he couldn’t have her, then no-one could.

IN PART TWO

A fateful stroll

A case for the police

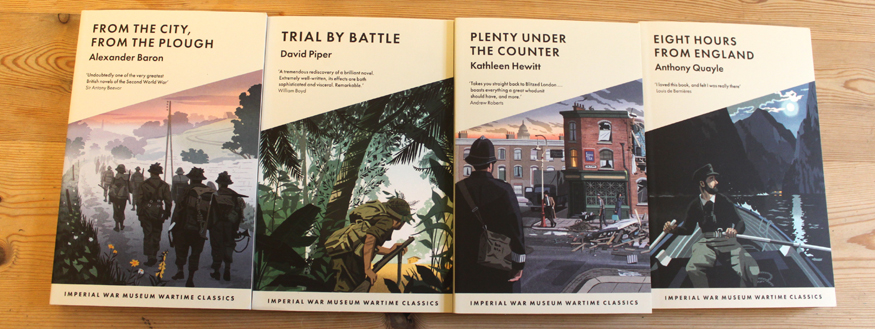

This is a vivid and moving account of preparations for D- Day and the advance into Normandy. Published in the 75th anniversary year of the D-Day landings, this is based on the author’s first-hand experience of D-Day and has been described by Antony Beevor as:

This is a vivid and moving account of preparations for D- Day and the advance into Normandy. Published in the 75th anniversary year of the D-Day landings, this is based on the author’s first-hand experience of D-Day and has been described by Antony Beevor as: This quietly shattering and searingly authentic depiction of the claustrophobia of jungle warfare in Malaya was described by William Boyd as:

This quietly shattering and searingly authentic depiction of the claustrophobia of jungle warfare in Malaya was described by William Boyd as: Anthony Quayle was a renowned Shakespearean actor, director and film star and this is his candid account of SOE operations in occupied Europe. Historian and journalist Andrew Roberts said:

Anthony Quayle was a renowned Shakespearean actor, director and film star and this is his candid account of SOE operations in occupied Europe. Historian and journalist Andrew Roberts said: This murder mystery about opportunism and the black market is set against the backdrop of London during the Blitz.

This murder mystery about opportunism and the black market is set against the backdrop of London during the Blitz.

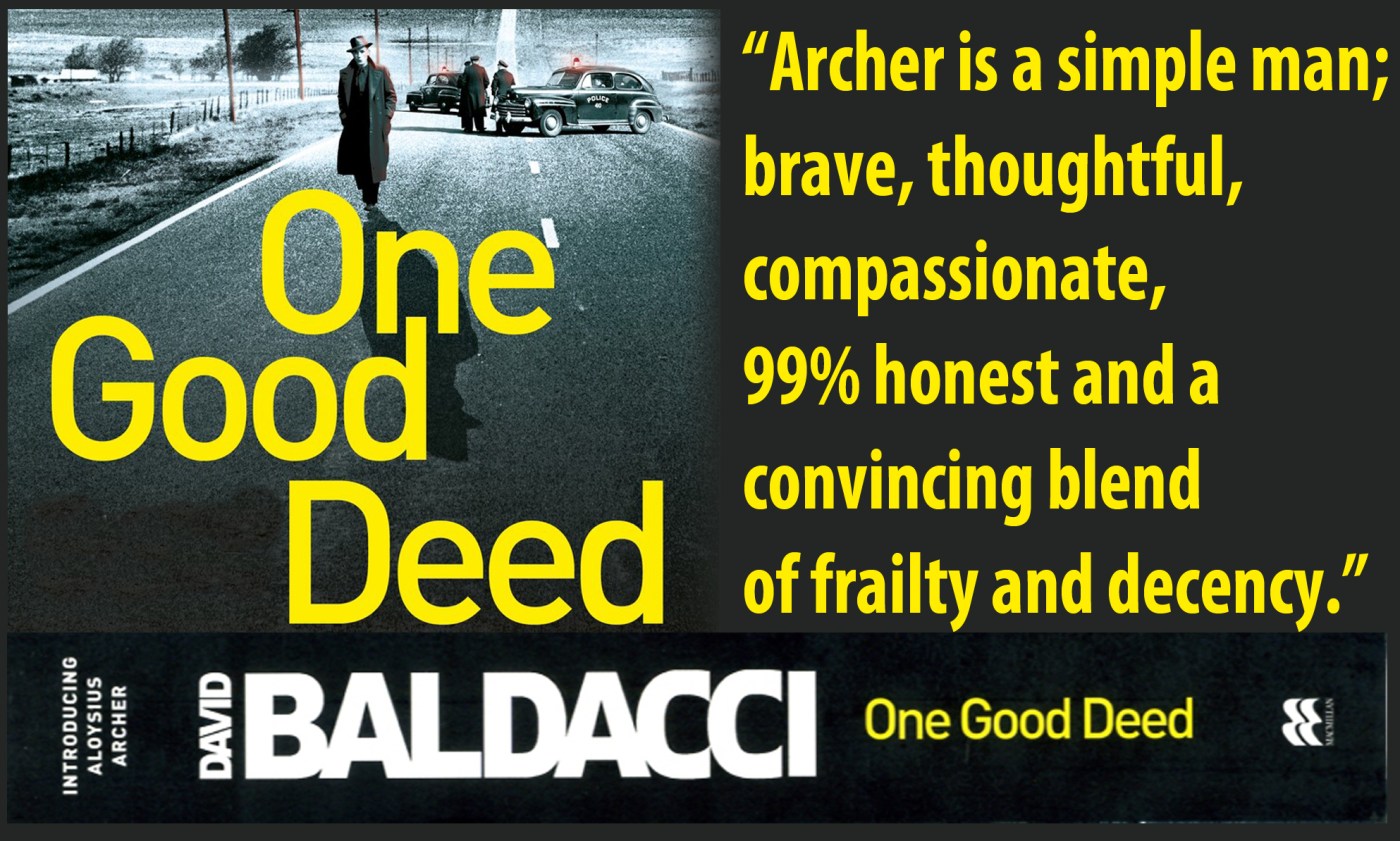

rcher served his country with distinction in the war, fighting his way up the spine of Italy, watching his buddies die hard, and wondering about the ‘just cause’ that has trained him to shoot, throttle, stab and maim fellow human beings while, at the same time, preventing him from being at the deathbeds of both parents.

rcher served his country with distinction in the war, fighting his way up the spine of Italy, watching his buddies die hard, and wondering about the ‘just cause’ that has trained him to shoot, throttle, stab and maim fellow human beings while, at the same time, preventing him from being at the deathbeds of both parents. Wearing a cheap suit, regarded as trash by the local people, and with every cause to feel bitter, Archer checks into the Derby Hotel and contemplates the future. His immediate task is to check in with his Probation Officer, Ernestine Crabtree. Quietly impressed by her demeanour – and her physical charm – Archer goes, in spite of his parole restrictions, for a drink in a local bar, The Cat’s Meow

Wearing a cheap suit, regarded as trash by the local people, and with every cause to feel bitter, Archer checks into the Derby Hotel and contemplates the future. His immediate task is to check in with his Probation Officer, Ernestine Crabtree. Quietly impressed by her demeanour – and her physical charm – Archer goes, in spite of his parole restrictions, for a drink in a local bar, The Cat’s Meow ven before Lucas Tuttle answers the door to Archer’s knock by pointing a cocked Remington shotgun at his unwelcome visitor, Archer has learned that the floozie on Pittleman’s arm in the bar is none other than Jackie, Tuttle’s estranged daughter. Archer finds the coveted motor car hidden away on Tuttle’s ranch, but it has been deliberately torched. Cursing his involvement in this blood feud, Archer’s equilibrium and freedom both take a severe knock when Pittleman’s body is found in a bedroom just along the floor from Archer’s room in The Derby. Thrown into the cells as the obvious suspect, Archer is released when he meets up with Irving Shaw – a serious and competent detective – and convinces him of his innocence.

ven before Lucas Tuttle answers the door to Archer’s knock by pointing a cocked Remington shotgun at his unwelcome visitor, Archer has learned that the floozie on Pittleman’s arm in the bar is none other than Jackie, Tuttle’s estranged daughter. Archer finds the coveted motor car hidden away on Tuttle’s ranch, but it has been deliberately torched. Cursing his involvement in this blood feud, Archer’s equilibrium and freedom both take a severe knock when Pittleman’s body is found in a bedroom just along the floor from Archer’s room in The Derby. Thrown into the cells as the obvious suspect, Archer is released when he meets up with Irving Shaw – a serious and competent detective – and convinces him of his innocence. Pretty much left on his own to solve the case after a violent attempt to silence Jackie, Archer has to summon up very ounce of his military experience and his innate common sense to put himself beyond the reach of the hangman’s noose.

Pretty much left on his own to solve the case after a violent attempt to silence Jackie, Archer has to summon up very ounce of his military experience and his innate common sense to put himself beyond the reach of the hangman’s noose.

The River Thames plays a central part in The Ring. Although Joseph Bazalgette’s efforts to clean it up with his sewerage works were almost complete, the river was still a bubbling and noxious body of dirty brown effluent, not helped by the frequent appearance of human bodies bobbing along on its tides. In this case, however, we must say that the bodies come in instalments, as someone has been chopping them to bits. PC Crossland makes the first grisly discovery:

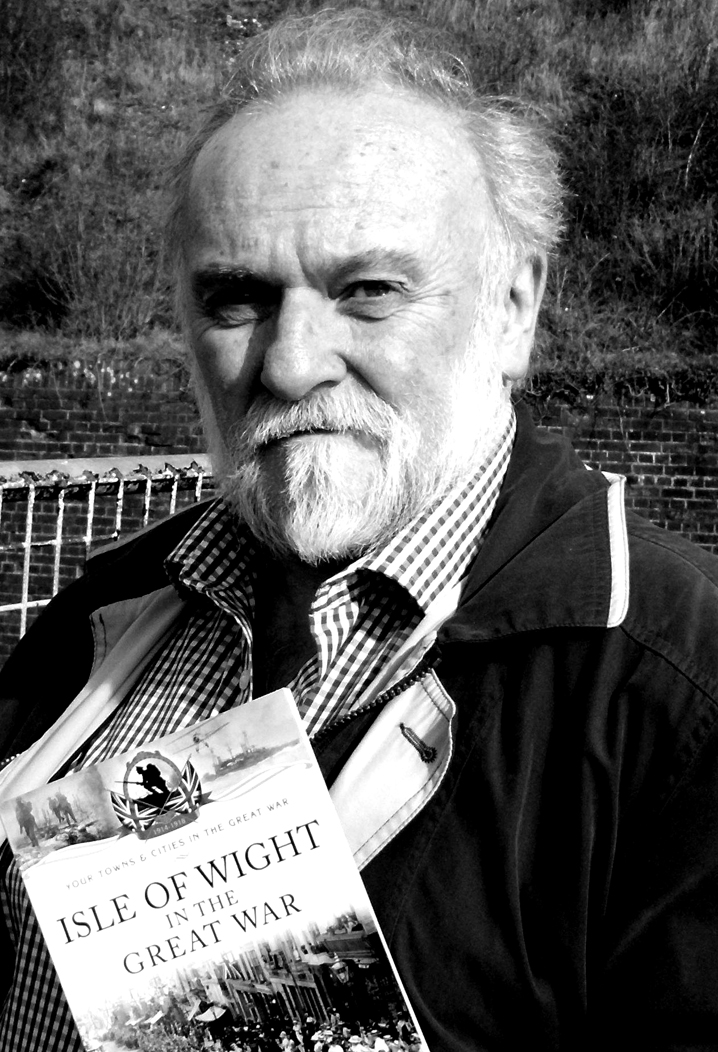

The River Thames plays a central part in The Ring. Although Joseph Bazalgette’s efforts to clean it up with his sewerage works were almost complete, the river was still a bubbling and noxious body of dirty brown effluent, not helped by the frequent appearance of human bodies bobbing along on its tides. In this case, however, we must say that the bodies come in instalments, as someone has been chopping them to bits. PC Crossland makes the first grisly discovery: MJ Trow (right) has been entertaining us for over thirty years with such series at the Inspector Lestrade novels and the adventures of the semi-autobiographical school master detective Peter Maxwell. Long-time readers will know that jokes are never far away, even when the pages are littered with sudden death, violence and a profusion of body parts. Grand and Batchelor eventually solve the mystery of what happened to Emilia Byng, both helped and hindered by the ponderous ‘Daddy’ Bliss and a random lunatic, recently escaped from Broadmoor. Trow writes with panache and a love of language equalled by few other British writers. His grasp of history is unrivalled, but he wears his learning lightly. The Ring is a bona fide crime mystery, but the gags are what lifts the narrative from the ordinary to the sublime:

MJ Trow (right) has been entertaining us for over thirty years with such series at the Inspector Lestrade novels and the adventures of the semi-autobiographical school master detective Peter Maxwell. Long-time readers will know that jokes are never far away, even when the pages are littered with sudden death, violence and a profusion of body parts. Grand and Batchelor eventually solve the mystery of what happened to Emilia Byng, both helped and hindered by the ponderous ‘Daddy’ Bliss and a random lunatic, recently escaped from Broadmoor. Trow writes with panache and a love of language equalled by few other British writers. His grasp of history is unrivalled, but he wears his learning lightly. The Ring is a bona fide crime mystery, but the gags are what lifts the narrative from the ordinary to the sublime: