Think the beautiful county of Suffolk, with its stately churches and half-timbered villages. Think the timeless Stour and Deben valleys and their rivers, where the sun dapples the glinting water, much as it did when Constable immortalised the scene. Think antiques. Think crime and intrigue. Remind you of Sunday nights back in the day? It reminds me of the antics of Lovejoy and his friends, thirty years ago. However, this is rather different. We are in the present day, and the central character is Freya Lockwood, a skilled antique hunter who has fallen on hard times. Her former husband has let her keep their house until their daughter grew up, but now he wants it back and she is, to paraphrase the great Derek Raymond, rather like the crust on its uppers.

Freya’s background has elements of tragedy. As a schoolgirl, she was badly burned in the house fire that killed her parents, and she was brought up by her aunt Carole and began her working career as an assistant to antiques expert Arthur Crockleford. At some point they had a major falling out, and haven’t spoken in years. When Freya gets a ‘phone call from Carole to say that Arthur has been found dead in his shop, she ups sticks and travels down to Little Meddington where he had his shop.

The police have decided that Arthur’s demise is a simple case of an elderly man falling down the stairs, but then Freya and Carole are handed a letter addressed to them which begins:

“If you are holding this letter in your hands then it is over for me..”

Is there more to Arthur’s death than meets the eye? We know there is, because of the first few pages of the book, but Freya and Carole are in the dark after subsequently being told by a solicitor that the shop and its contents are now theirs. They begin to pick away at the mystery.

Arthur has arranged an antiques weekend to be held, in the event of his death, at Copthorne Manor a nearby minor stately home. He has invited several people connected with the antiques world to stay at the Manor, and it is as if he will be conducting the consequent opera like a maestro from beyond the grave.

We learn that the falling out between Freya and Arthur was a tragedy that occurred in Cairo many years earlier, Arthur and Freya were in Egypt ostensibly verifying and valuing certain items which were thought to have been stolen and were being traded on the antiques black market. Freya fell in love with a with a young Egyptian, Asim, whose family firm specialised in creating very cleverly faked antiquities. When a deal goes wrong, Asim is found dead, and Arthur sends Freya back to England. They have not spoken since, as Freya believes that Arthur was responsible for her lover’s death.

Now, back in Suffolk, at Copthorne Manor, some of the people involved in the Cairo incident are together again under the same roof, and in the vaults of the house are packing crates which contain some of the items which were central to Asim’s murder.

Everyone wants to get their hands on the precious items, but no-one is who they seem to be. The country house setting allows author Cara Miller to run through the full repertoire of Golden Age tropes, including thunderstorms, power cuts and corpses, and she has great fun as Freya and Carole eventually expose the villains.

Cara Miller (above) is the daughter of the late Judith Miller of Antiques Roadshow fame, so she certainly knows her stuff. The novel is a splendid mix of murder, mayhem and outrageous characters, and will delight those who love a good old fashioned mystery, with more than a hint of the Golden Age. It is published by Macmillan, and is available now.

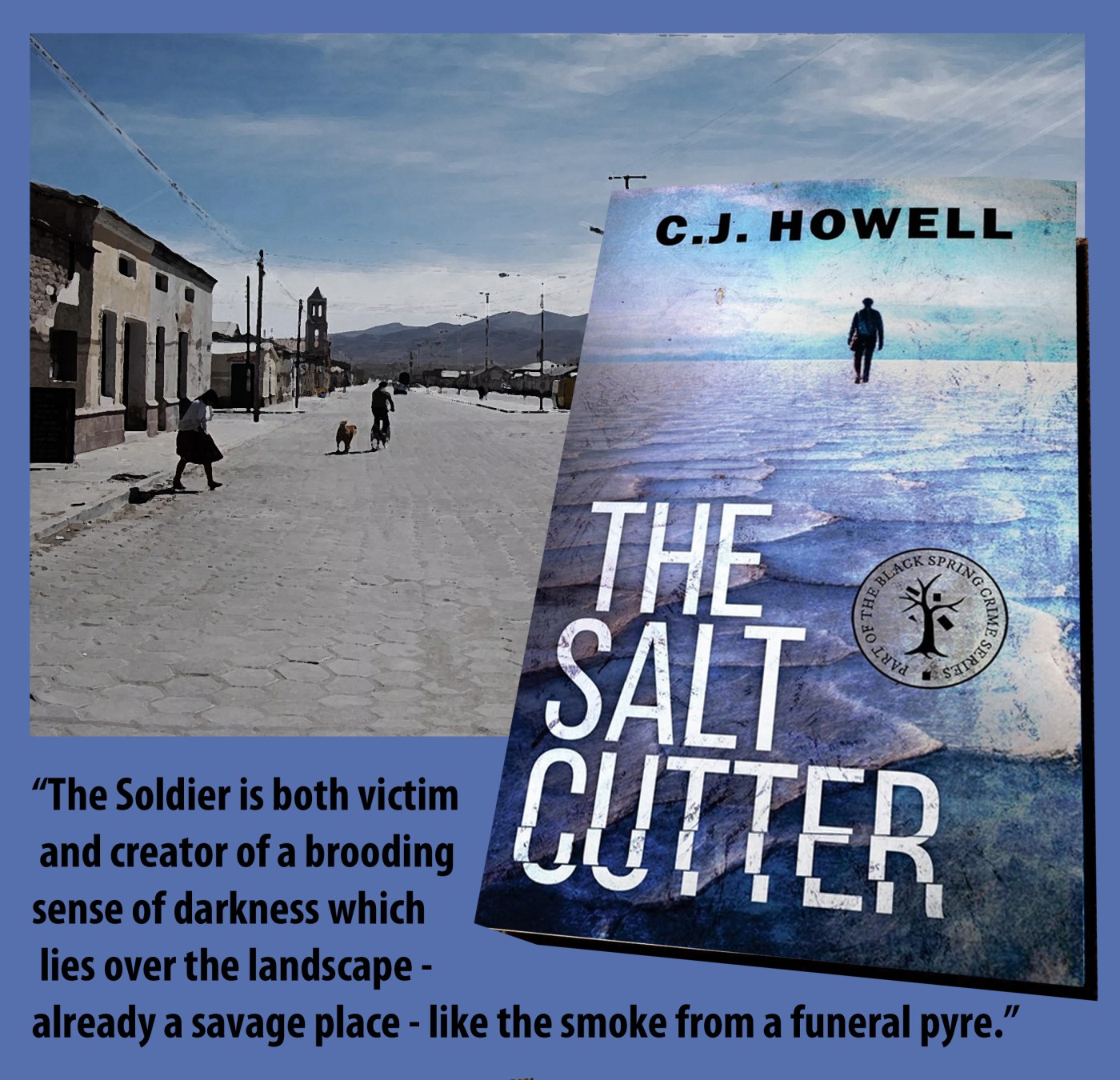

Ask ten different readers what they think qualifies as ‘noir’ and you will get ten different answers. Is it that everything is framed in a 1950s monochrome? Is it because all the participants behave badly towards each other, and have zero respect for themselves? Is it because we know that when we turn the final page, there will be no outcome that could be described as optimistic or redemptive? One quality, for me, has to be an unremitting sense of bleakness – both physical and moral – and this novel by CJ Howell (left) certainly has that.

Ask ten different readers what they think qualifies as ‘noir’ and you will get ten different answers. Is it that everything is framed in a 1950s monochrome? Is it because all the participants behave badly towards each other, and have zero respect for themselves? Is it because we know that when we turn the final page, there will be no outcome that could be described as optimistic or redemptive? One quality, for me, has to be an unremitting sense of bleakness – both physical and moral – and this novel by CJ Howell (left) certainly has that.