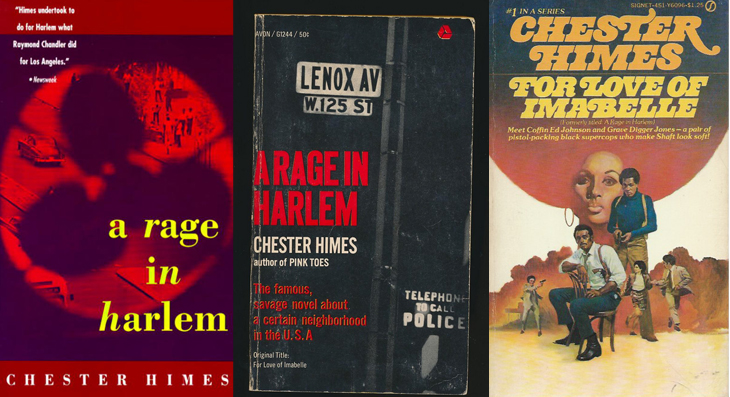

Chester Himes was born into a middle-class family in Jefferson City, Missouri, in 1909. His parents both worked in education. When Himes was 12, his brother was blinded in an accident, and was denied treatment by the Jim Crow Laws (extensive segregation in all public services) and this shaped the way Himes viewed American society at the time. The family moved to Ohio, and after his parents divorced, Himes fell among thieves and in 1928 took part in an armed robbery, for which he was sentenced to 25 years hard labour. In prison, he began to write feature stories and articles for magazines. In 1936 he was released into the custody of his mother and, while working dead-end jobs, he continued to write. He moved to Los Angeles in the 1940s to write for movies but again, he felt the heavy hand of racial discrimination. He finally gave upon America, and moved to Paris in the 1950s. He never returned to America and died in Spain in 1984.

Chester Himes was born into a middle-class family in Jefferson City, Missouri, in 1909. His parents both worked in education. When Himes was 12, his brother was blinded in an accident, and was denied treatment by the Jim Crow Laws (extensive segregation in all public services) and this shaped the way Himes viewed American society at the time. The family moved to Ohio, and after his parents divorced, Himes fell among thieves and in 1928 took part in an armed robbery, for which he was sentenced to 25 years hard labour. In prison, he began to write feature stories and articles for magazines. In 1936 he was released into the custody of his mother and, while working dead-end jobs, he continued to write. He moved to Los Angeles in the 1940s to write for movies but again, he felt the heavy hand of racial discrimination. He finally gave upon America, and moved to Paris in the 1950s. He never returned to America and died in Spain in 1984.

A Rage In Harlem was published in 1957, but with the title For Love of Imabelle. It was the first in a series of books featuring New York detectives Coffin Ed Johnson and Grave Digger Jones, but it is a while before they take the stage. The book tells the tale of a deluded man named Jackson who, for the love of his woman, Imabelle, is dumb enough to fall for a scheme which is a kind of mid twentieth century alchemy. All you have to do is to give a bunch of ten dollar bills to ‘the man’ and he will, by an amazing feat of chemistry (it involves stuffing the notes in to the chimney of a stove) turn each ten into a hundred.

Needless to say, the advertised miracle doesn’t take place, and Jackson is left in a whole heap of trouble. Johnson and Jones – Jones only appears briefly in a violent fight – are largely peripheral to the action, but they were to play more central roles in future books in the series. The men who swindled Jackson are, however, not simply con-men. They are violent criminals wanted for murder in Mississippi, and for them, killing is simply an tool of the trade.  Rage In Harlem is a very angry book, and the psychological scars borne by Himes are unhealed and very near the surface. There is a solid core of what appears to be slapstick comedy, but it is brutal, surreal and venomous. The mother of all car chase takes place when Jackson – an undertaker’s chauffeur – steals a hearse to shift what he thinks is a trunk full of gold ore (another scam). He is unaware that it also contains the dead body of his brother who, by the way, makes a living by dressing as a nun and soliciting alms while reciting bogus quotations from The Book of Revelations:

Rage In Harlem is a very angry book, and the psychological scars borne by Himes are unhealed and very near the surface. There is a solid core of what appears to be slapstick comedy, but it is brutal, surreal and venomous. The mother of all car chase takes place when Jackson – an undertaker’s chauffeur – steals a hearse to shift what he thinks is a trunk full of gold ore (another scam). He is unaware that it also contains the dead body of his brother who, by the way, makes a living by dressing as a nun and soliciting alms while reciting bogus quotations from The Book of Revelations:

“Underneath the trunk black cloth was piled high. Artificial flowers were scattered in garish disarray. A horseshoe wreath of artificial lilies had slipped to the back. Looking out from the arch of white lilies was a black face. The face was looking backward from a head-down position, resting on the back of the skull. A white bonnet sat atop a gray wig which had fallen askew. The face wore a horrible grimace of pure evil. White-walled eyes stared at the four gray men with a fixed, unblinking stare. Beneath the face was the huge purple-lipped wound of a cut throat.”

For all Jackson’s gullibility, Himes clearly admires the fat little man’s spirit:

“She …. looked him straight in the eyes with her own glassy, speckled bedroom eyes.

The man drowned.

When he came up, he stared back, passion cocked, his whole black being on a live-wired edge. Ready! Solid ready to cut throats, crack skulls, dodge police, steal hearses, drink muddy water, live in a hollow log and take any rape-fiend chance to be once more in the arms of his high-yellow heart.”

Himes is less charitable about other chancers and frauds in the city. When Jackson makes his getaway in the hearse:

“Pedestrians were scattered in grotesque fight. A blind man jumped over a bicycle trying to get away.”

And this is Harlem in the morning:

“Later, the downtown office porters would pour from the crowded flats in a steady stream, carrying polished leather briefcases stuffed with overalls to look like businessmen, and buy the Daily News to read on the subway.”

The astonishing thing is that I can’t find any record of Himes living in or spending time in New York, let alone Harlem. He wrote the book while he was living among other exiles – like James Baldwin – in Paris. The French loved this and his later books, but back home in America, apart from literary circles on the West Coast, readers were not interested. A Rage In Harlem has been reissued by Penguin Modern Classics and will be available on 25th March.

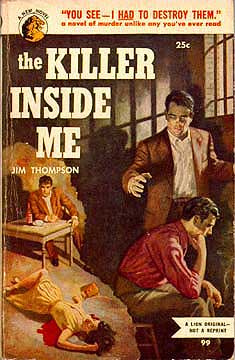

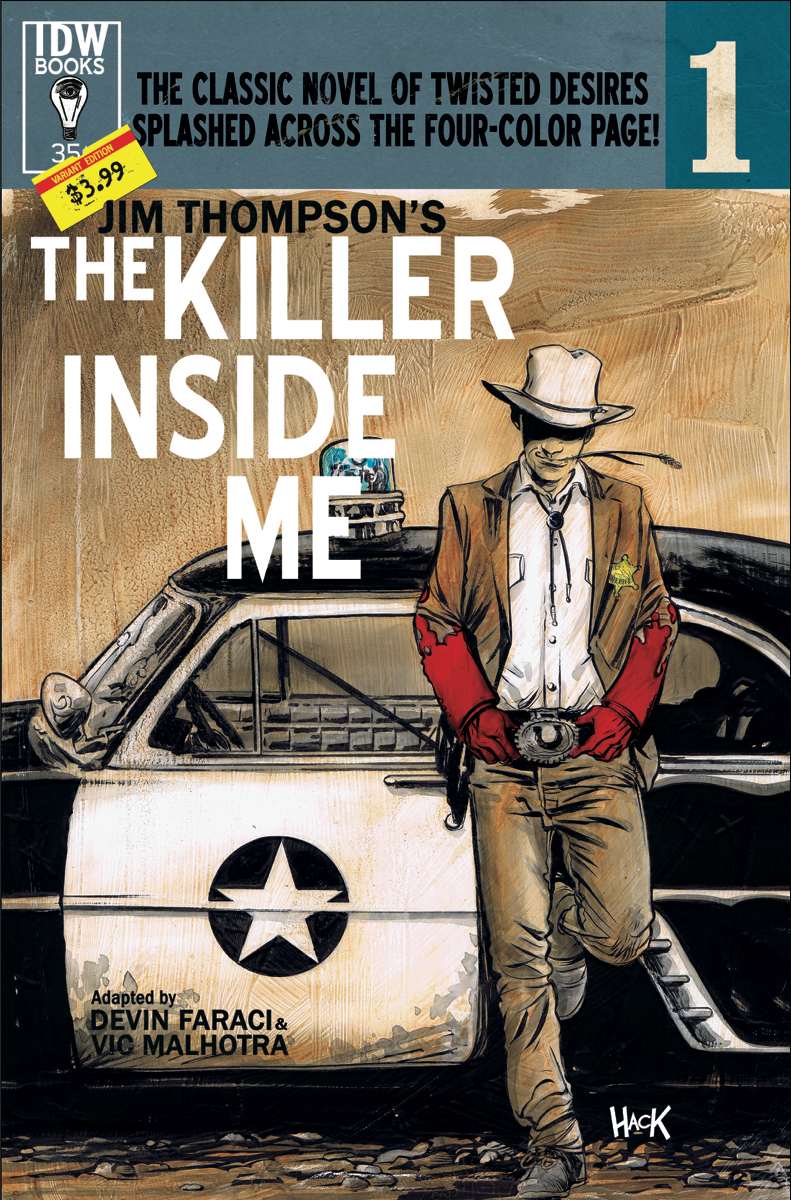

Thompson’s first major success came in 1952 with The Killer Inside Me and it remains grimly innovative. Psychopathic killers have become pretty much mainstream in contemporary crime fiction, but there can be few who chill the blood in quite the same way as Thompson’s West Texas Deputy Sheriff Lou Ford. His menace is all the more compelling because he is the narrator of the novel, and a few hundred words in we are left in no doubt that the dull but amiable law officer, who bores local people stupid with his homespun cod-philosophical clichés, is actually a creature from the darkest reaches of hell.

Thompson’s first major success came in 1952 with The Killer Inside Me and it remains grimly innovative. Psychopathic killers have become pretty much mainstream in contemporary crime fiction, but there can be few who chill the blood in quite the same way as Thompson’s West Texas Deputy Sheriff Lou Ford. His menace is all the more compelling because he is the narrator of the novel, and a few hundred words in we are left in no doubt that the dull but amiable law officer, who bores local people stupid with his homespun cod-philosophical clichés, is actually a creature from the darkest reaches of hell. Joyce is savvy, and world-weary, but when Ford’s “pardon me, Ma’am,” charm strikes the wrong note, she slaps him. He slaps her back and the encounter takes a dark turn when Ford takes off his belt and gives Joyce what used to be known as “a leathering.” She responds to the beating with obvious arousal, and the pair begin a violent sado-sexual affair.

Joyce is savvy, and world-weary, but when Ford’s “pardon me, Ma’am,” charm strikes the wrong note, she slaps him. He slaps her back and the encounter takes a dark turn when Ford takes off his belt and gives Joyce what used to be known as “a leathering.” She responds to the beating with obvious arousal, and the pair begin a violent sado-sexual affair. A key figure in Ford’s life is Amy, his long-time girlfriend. Thompson paints her as physically attractive, but socially constrained. She is a primary school teacher from a good local family who, despite responding to Ford’s violent sexual ways, is determined to marry him. As the dark clouds of suspicion begin to shut the daylight out of Lou Ford’s life, she is the next to die, and Ford’s clumsy attempt to frame someone else for her death is the tipping point. Thereafter his downfall is rapid, and his final moments are as brutal and savage as anything he has inflicted on other people.

A key figure in Ford’s life is Amy, his long-time girlfriend. Thompson paints her as physically attractive, but socially constrained. She is a primary school teacher from a good local family who, despite responding to Ford’s violent sexual ways, is determined to marry him. As the dark clouds of suspicion begin to shut the daylight out of Lou Ford’s life, she is the next to die, and Ford’s clumsy attempt to frame someone else for her death is the tipping point. Thereafter his downfall is rapid, and his final moments are as brutal and savage as anything he has inflicted on other people.

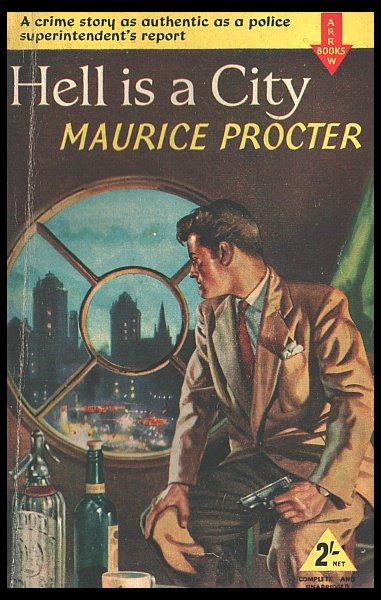

he name Maurice Procter is not one that is regularly bandied around at crime fiction festivals when the Great and The Good are discussing pioneering and innovative writers of the past. He is, just about, still in print thanks to the wonders of Kindle and specialist reprinters such as Murder Room. I’m reluctant to use the fatal words “in his day”, but Procter was a prolific and popular writer of crime novels between 1947 and 1969.

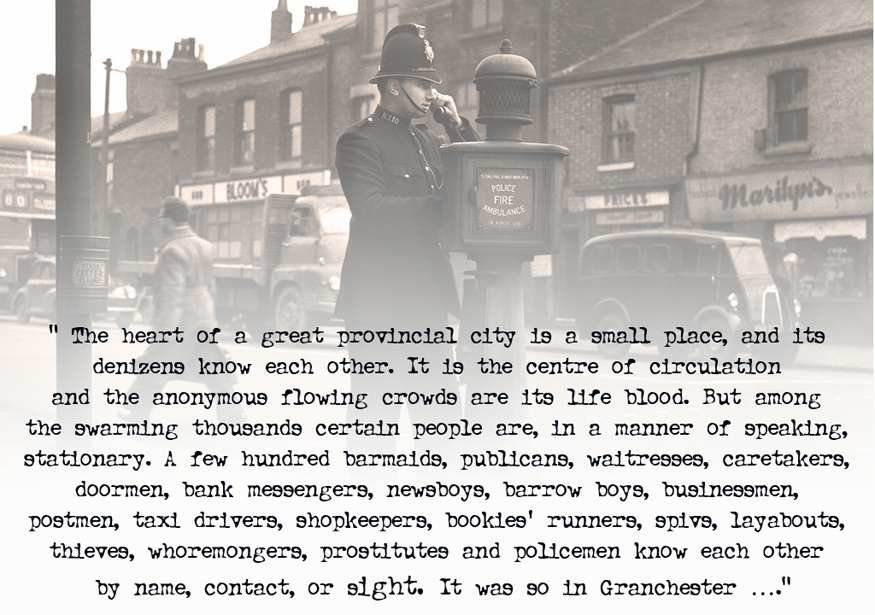

he name Maurice Procter is not one that is regularly bandied around at crime fiction festivals when the Great and The Good are discussing pioneering and innovative writers of the past. He is, just about, still in print thanks to the wonders of Kindle and specialist reprinters such as Murder Room. I’m reluctant to use the fatal words “in his day”, but Procter was a prolific and popular writer of crime novels between 1947 and 1969. Born in the Lancashire weaving town of Nelson, Procter (left) joined the police force in nearby Halifax in 1927 and remained a serving officer until the success of his novels enabled him to write full time. In 1954 he published the first of a fifteen book series of police procedurals featuring Detective Inspector Harry Martineau. Martineau is a detective in the city of Granchester. Replace the ‘Gr’ with “M’ and you have the actual location pegged.

Born in the Lancashire weaving town of Nelson, Procter (left) joined the police force in nearby Halifax in 1927 and remained a serving officer until the success of his novels enabled him to write full time. In 1954 he published the first of a fifteen book series of police procedurals featuring Detective Inspector Harry Martineau. Martineau is a detective in the city of Granchester. Replace the ‘Gr’ with “M’ and you have the actual location pegged.

tarling wastes no time in organising his next heist, and it is a daring cash grab. The victims are two hapless young clerks who work for city bookmaker Gus Hawkins. On their way to the bank with a satchel full of takings from Doncaster races, they are waylaid. Colin Lomax is coshed and left with a serious head injury but Cicely Wainwright fares even worse. Because the money bag is chained to her wrist, she is flung into the back of the getaway van and is killed by Starling as the gang make their escape over the moors to the east of the city. The bag is cut from Cicely’s wrist, and her body is dumped. Of course, this ups the stakes, much to the discomfort of Starling’s gang members, each of whom realises that they face the hangman’s noose if they are caught and convicted as accessories to murder. The hangman, by the way, is a well-known local resident:

tarling wastes no time in organising his next heist, and it is a daring cash grab. The victims are two hapless young clerks who work for city bookmaker Gus Hawkins. On their way to the bank with a satchel full of takings from Doncaster races, they are waylaid. Colin Lomax is coshed and left with a serious head injury but Cicely Wainwright fares even worse. Because the money bag is chained to her wrist, she is flung into the back of the getaway van and is killed by Starling as the gang make their escape over the moors to the east of the city. The bag is cut from Cicely’s wrist, and her body is dumped. Of course, this ups the stakes, much to the discomfort of Starling’s gang members, each of whom realises that they face the hangman’s noose if they are caught and convicted as accessories to murder. The hangman, by the way, is a well-known local resident: I was quickly hooked by this novel, for a variety of reasons. Anyone who has driven east out of Manchester in the direction of Sheffield (which makes a brief apparance as Hallam City) will recognise the changeless face of the moors, with their isolated pubs and gritstone houses clinging to the roadside. What has changed, however, is the view back towards Manchester. Where, in the early 1950s Martineau saw mill chimneys belching smoke, today we could probably, apart from the haze of vehicle emissions , see almost to the Irish Sea. We also know that Cicely Wainwright’s’s body would not be the last to be abandoned in the cottongrass, heather and bilberry of the Dark Peak.

I was quickly hooked by this novel, for a variety of reasons. Anyone who has driven east out of Manchester in the direction of Sheffield (which makes a brief apparance as Hallam City) will recognise the changeless face of the moors, with their isolated pubs and gritstone houses clinging to the roadside. What has changed, however, is the view back towards Manchester. Where, in the early 1950s Martineau saw mill chimneys belching smoke, today we could probably, apart from the haze of vehicle emissions , see almost to the Irish Sea. We also know that Cicely Wainwright’s’s body would not be the last to be abandoned in the cottongrass, heather and bilberry of the Dark Peak.

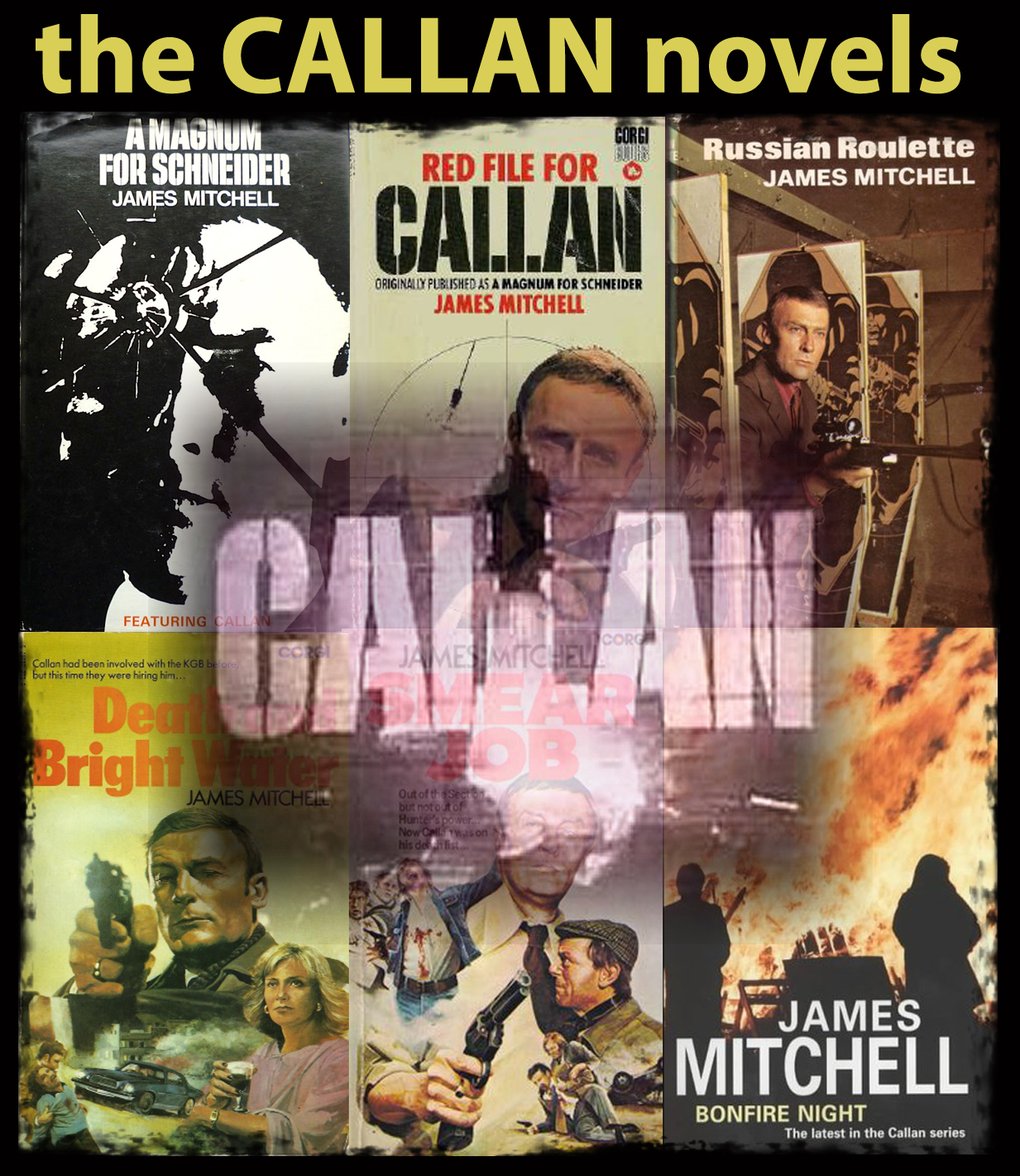

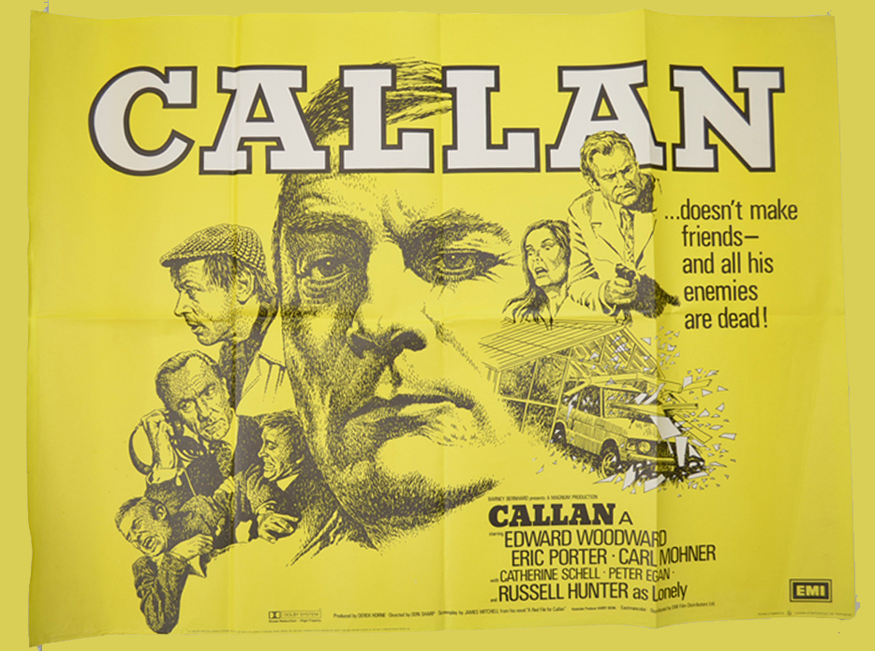

There had been big changes since the last novel appeared a year earlier. The tv series had finished and Callan had transferred to the cinema in a moderately successful feature film (apparently the first to utilise Dolby sound). It seems that James Mitchell saw Callan’s future as on the big screen. The plots of this novel and the next one reflect that change.

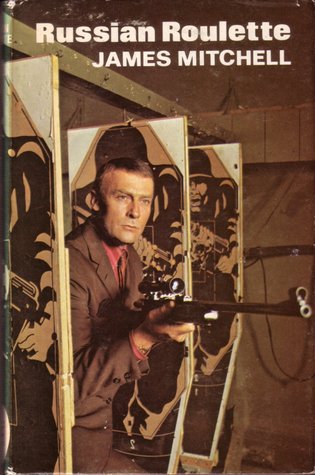

There had been big changes since the last novel appeared a year earlier. The tv series had finished and Callan had transferred to the cinema in a moderately successful feature film (apparently the first to utilise Dolby sound). It seems that James Mitchell saw Callan’s future as on the big screen. The plots of this novel and the next one reflect that change. By now Callan (and Lonely) are more or less free agents, pursuing lucrative careers in the world of personal security. The Section exists only to tie them, and potential readers, to the TV series.

By now Callan (and Lonely) are more or less free agents, pursuing lucrative careers in the world of personal security. The Section exists only to tie them, and potential readers, to the TV series. Written when James Mitchell was old and unwell, and published a year before his death, this is something of a curio. Callan has been free of the Section for at least a decade, and in that time he and Lonely have made vast fortunes in the electronics business. This at least follows on from the conclusion of the previous novel, when Callan and Lonely were establishing something of a living outside the Section. But the plot, which need not detain us here, is difficult to credit when it’s not merely confusing. The book is not without its moments, but is for Callan completists only.

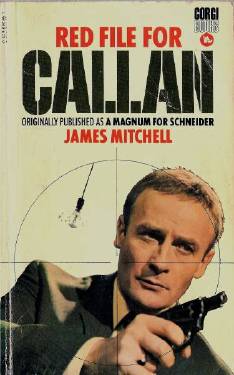

Written when James Mitchell was old and unwell, and published a year before his death, this is something of a curio. Callan has been free of the Section for at least a decade, and in that time he and Lonely have made vast fortunes in the electronics business. This at least follows on from the conclusion of the previous novel, when Callan and Lonely were establishing something of a living outside the Section. But the plot, which need not detain us here, is difficult to credit when it’s not merely confusing. The book is not without its moments, but is for Callan completists only. The first Callan novel, and perhaps the locus classicus of all Callan plots, on page and screen: A disillusioned Callan has left the Section and is living and working in reduced circumstances, until “persuaded” by Hunter to return and carry out one more job. The target is Herr Schneider who, once Callan knows more of him, doesn’t seem to be as black as he’s painted…

The first Callan novel, and perhaps the locus classicus of all Callan plots, on page and screen: A disillusioned Callan has left the Section and is living and working in reduced circumstances, until “persuaded” by Hunter to return and carry out one more job. The target is Herr Schneider who, once Callan knows more of him, doesn’t seem to be as black as he’s painted…

Although published in 1973 this book makes no reference to the events of high drama with which the final TV series concluded a year earlier. Here, Callan is still settled in the Section and all the supporting characters are in place.

Although published in 1973 this book makes no reference to the events of high drama with which the final TV series concluded a year earlier. Here, Callan is still settled in the Section and all the supporting characters are in place.

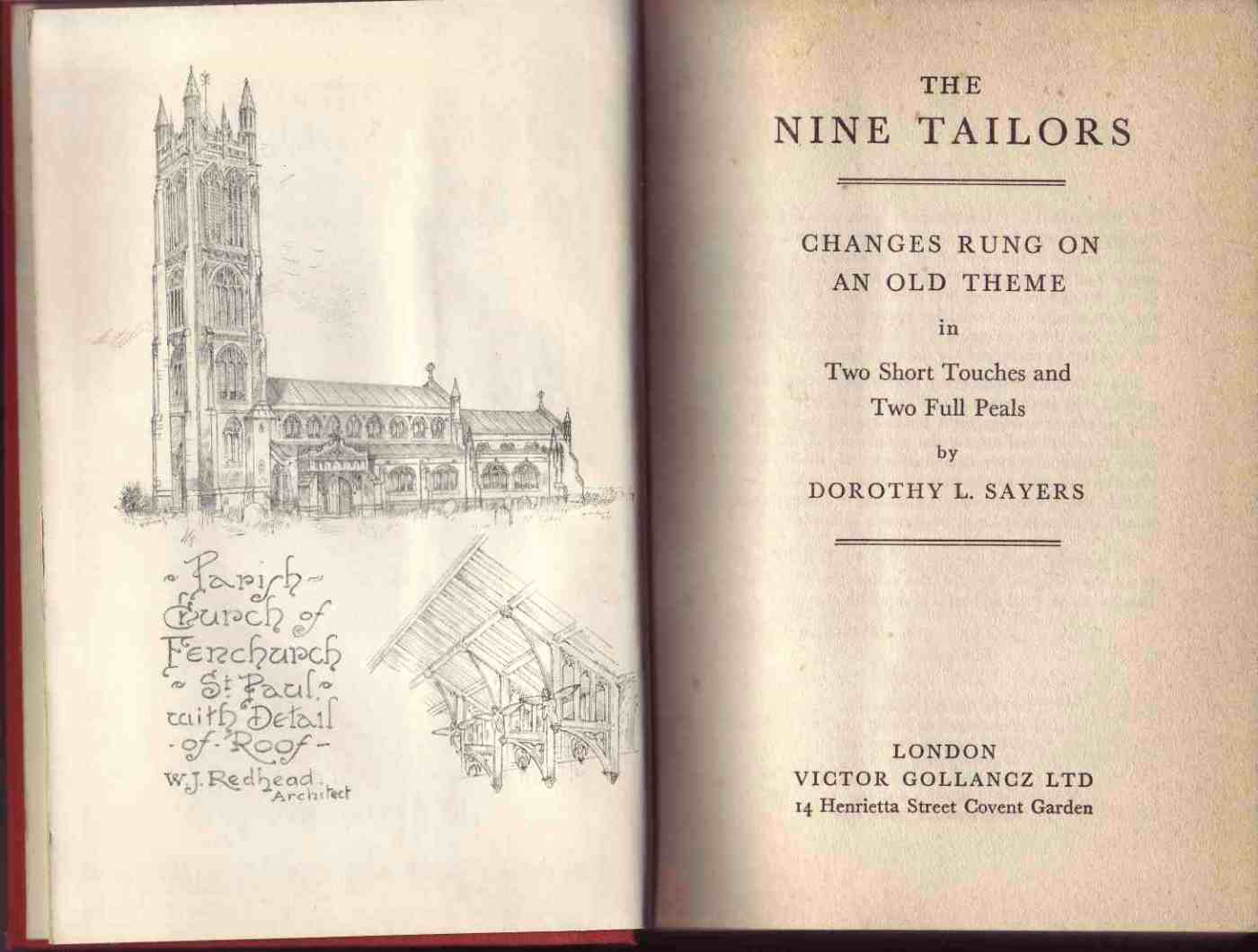

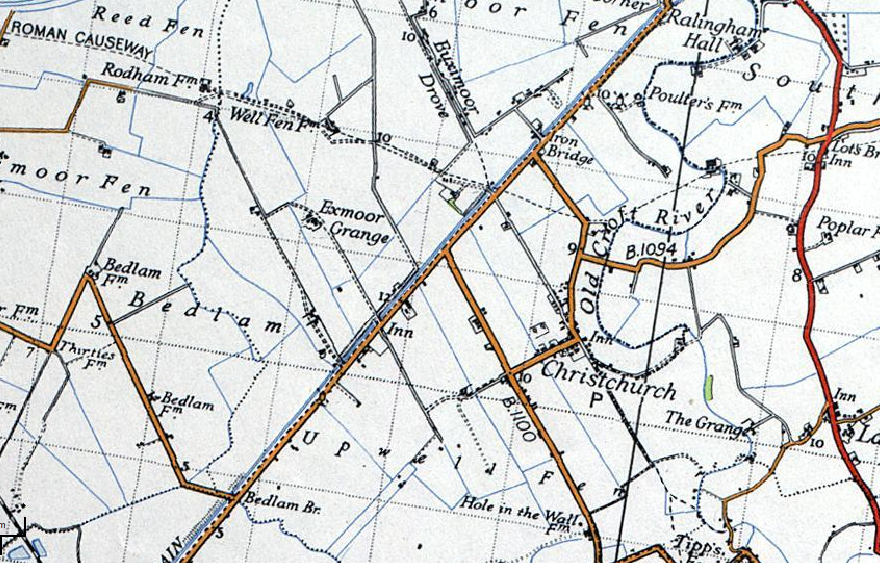

Let’s look at a few relatively simple background facts, and I apologise to fans of the author for whom this may be tedious. Dorothy Leigh Sayers (1893 – 1957) was a notable English writer, poet, classical scholar and dramatist. She introduced the aristocratic private detective Lord Peter Wimsey in her 1923 novel, Whose Body? and by the time The Nine Tailors was published in 1934, Wimsey and his imperturbable manservant Bunter were well established.

Let’s look at a few relatively simple background facts, and I apologise to fans of the author for whom this may be tedious. Dorothy Leigh Sayers (1893 – 1957) was a notable English writer, poet, classical scholar and dramatist. She introduced the aristocratic private detective Lord Peter Wimsey in her 1923 novel, Whose Body? and by the time The Nine Tailors was published in 1934, Wimsey and his imperturbable manservant Bunter were well established.

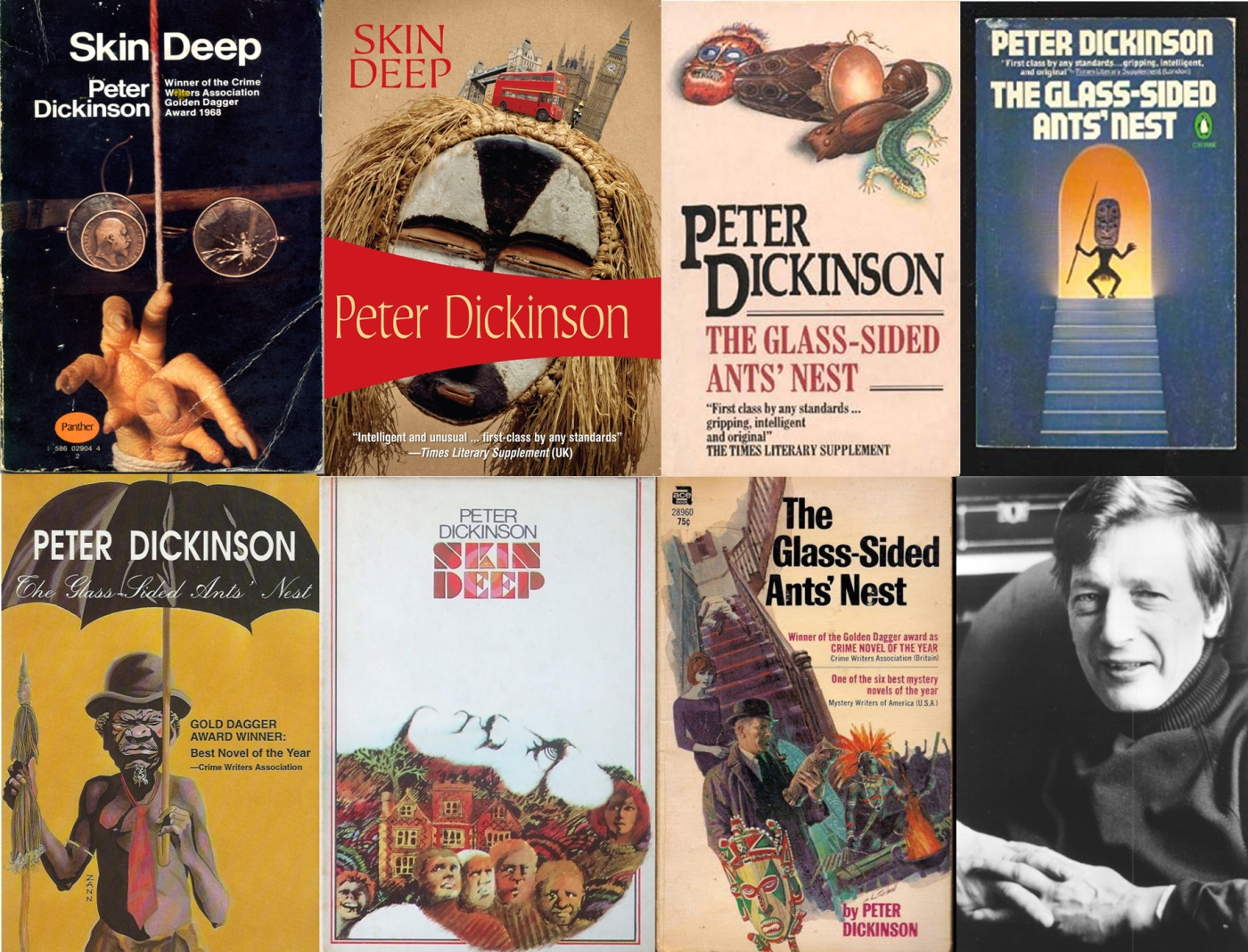

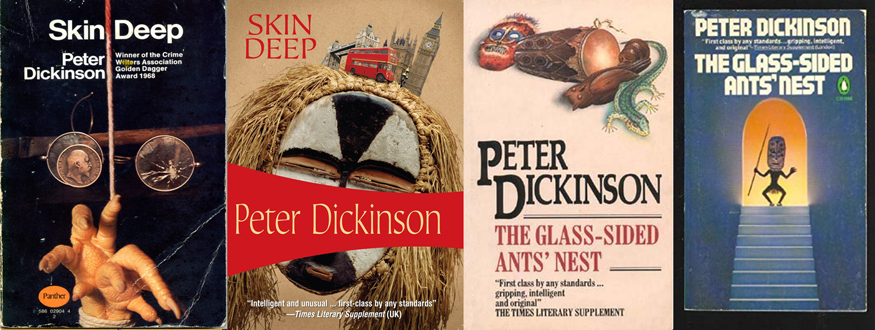

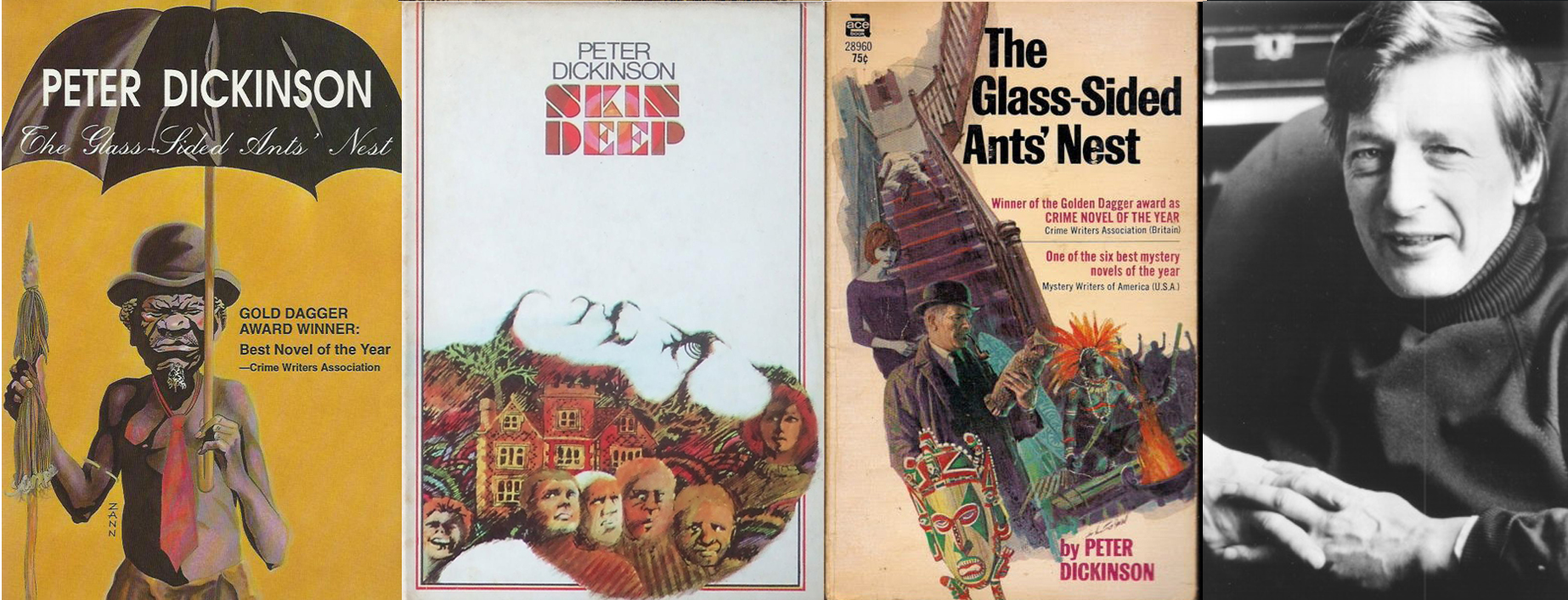

Incidentally, I don’t think there are many Old Etonian authors around these days, but Dickinson (left) was there from 1941 to 1946, and it is tempting to wonder if he ever rubbed shoulders in those years with another Eton scholar by the name of Robert William Arthur Cook, better known to us as the Godfather of English Noir

Incidentally, I don’t think there are many Old Etonian authors around these days, but Dickinson (left) was there from 1941 to 1946, and it is tempting to wonder if he ever rubbed shoulders in those years with another Eton scholar by the name of Robert William Arthur Cook, better known to us as the Godfather of English Noir

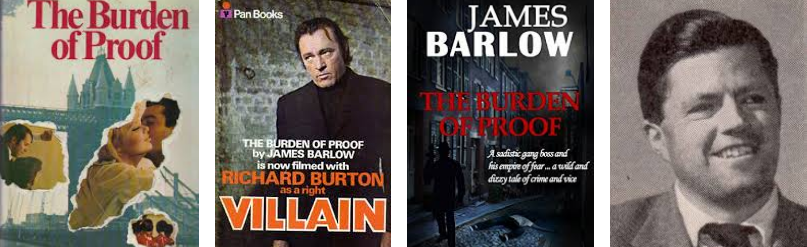

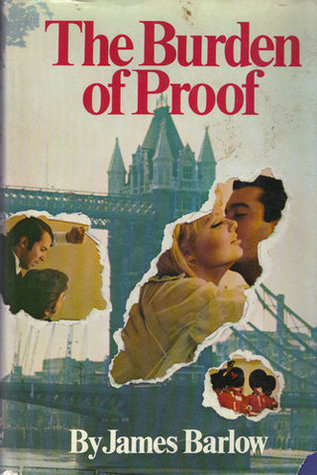

James Barlow was a Birmingham-born novelist who served as an air gunner with the RAF in WWII. Invalided out of service when he contracted tuberculosis, he faced a long convalescence. He began writing at this time, and after he worked in his native city as, of all things, a water rates inspector, he made the decision to write for a living. His first novel, The Protagonists, was published in 1956, but made little impact. It wasn’t until Term of Trial (1961) that he began to make a decent living from writing, and then more because film director Peter Glenville saw the cinematic potential in the story of an alcoholic school teacher whose career is threatened when he is accused of improper behaviour with a female pupil. The subsequent film had a star-studded cast including Sir Laurence Olivier, Simone Signoret, Sarah Miles, Terence Stamp, Hugh Griffith, Dudley Foster, Thora Hird and Alan Cuthbertson.

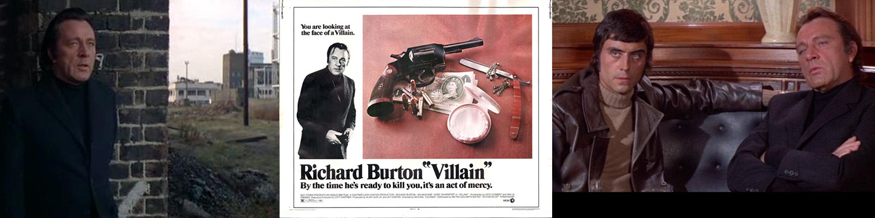

James Barlow was a Birmingham-born novelist who served as an air gunner with the RAF in WWII. Invalided out of service when he contracted tuberculosis, he faced a long convalescence. He began writing at this time, and after he worked in his native city as, of all things, a water rates inspector, he made the decision to write for a living. His first novel, The Protagonists, was published in 1956, but made little impact. It wasn’t until Term of Trial (1961) that he began to make a decent living from writing, and then more because film director Peter Glenville saw the cinematic potential in the story of an alcoholic school teacher whose career is threatened when he is accused of improper behaviour with a female pupil. The subsequent film had a star-studded cast including Sir Laurence Olivier, Simone Signoret, Sarah Miles, Terence Stamp, Hugh Griffith, Dudley Foster, Thora Hird and Alan Cuthbertson. Term of Trial was a powerful and controversial film, but clearly had nothing to do with crime fiction. Barlow’s 1968 novel The Burden of Proof was another matter. By the time it was published, the Kray twins’ days as despotic rulers of London’s gangland were numbered. They were arrested on 8th May in that year and the rest, as they say, is history. The Burden of Proof is centred on a Ronnie Kray-style gangster, Vic Dakin. Dakin is psychotic homosexual, devoted equally to his dear old mum and a succession of pliant boyfriends, while finding time to be at the hub of a violent criminal network.

Term of Trial was a powerful and controversial film, but clearly had nothing to do with crime fiction. Barlow’s 1968 novel The Burden of Proof was another matter. By the time it was published, the Kray twins’ days as despotic rulers of London’s gangland were numbered. They were arrested on 8th May in that year and the rest, as they say, is history. The Burden of Proof is centred on a Ronnie Kray-style gangster, Vic Dakin. Dakin is psychotic homosexual, devoted equally to his dear old mum and a succession of pliant boyfriends, while finding time to be at the hub of a violent criminal network.

In the city which is portrayed as little more than a moral sewer, we have the vile Dakin and his criminal associates; we have an earnest and incorruptible copper, Bob Matthews who Barlow sets up – along with Bob’s mild-mannered and decent wife Mary – as the apotheosis of what England used to be before the plague took hold. We have Gerald Draycott, a dishonest and manipulative MP who flirts with the dangerous world of gambling clubs, casinos, girls-for-hire and drugs-for-sale, but still dreams of becoming a cabinet minister.

In the city which is portrayed as little more than a moral sewer, we have the vile Dakin and his criminal associates; we have an earnest and incorruptible copper, Bob Matthews who Barlow sets up – along with Bob’s mild-mannered and decent wife Mary – as the apotheosis of what England used to be before the plague took hold. We have Gerald Draycott, a dishonest and manipulative MP who flirts with the dangerous world of gambling clubs, casinos, girls-for-hire and drugs-for-sale, but still dreams of becoming a cabinet minister.