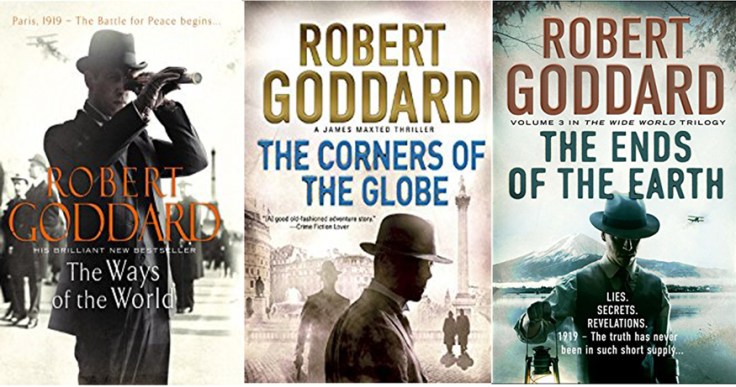

Robert Goddard and his ex-RAFC/RAF pilot and family black sheep James ‘Max’ Maxted start the ball rolling in our continuing look at crime fiction set in, or influenced by The Great War. Goddard introduced Maxted in 2013 with the first part of a trilogy, The Ways of the World. It is Spring 1919. The Great War is over. but a new war is beginning – a war of words and promises, both kept and broken and a war fought in the splendid hotels and conference halls of Paris. The victorious powers – Britain, France, the US, Italy and Japan – have sent their politicians and diplomats to the French capital to pick over the carcass of the old Europe. Amid the great and the good stands a young Englishman, James ‘Max’ Maxted. The ex-Royal Flying Corps pilot has come to Paris to investigate the mysterious death of his father, minor diplomat Sir Henry Maxted.

Max is used, first by an American wheeler-dealer called Ireton, then by the British Secret Service and other more shadowy organisations, to try to smoke out a German renegade called Lemmer. The story continues in The Corners of the Globe (2014). Max has still to uncover the truth about his father’s demise, and in addition to the Germans who will not accept defeat, there are some equally villainous Japanese thrown into the mix. The series concluded in 2015 with The Ends of the Earth, and it finds Max still battling the elusive Lemmer, but also locking horns with an evil Japanese aristocrat, Count Tamura. In some ways this is old-fashioned stuff, but there are hours of entertainment here for those who like their history spiced with danger and a couple of alluring femmes fatales. Max is an engaging character; a little old-school perhaps, with a nostalgic touch of Biggles and Bulldog Drummond, but equally brave and resourceful.

Robert Ryan, also known as Tom Neale, is an English author, journalist and screenwriter. He has written a host of successful adventure novels and thrillers, but our microscope focuses on his Dr Watson novels. He is not the first writer to exploit the potential of Sherlockiana, nor will he be the last. M J Trow wrote an entertaining series of books featuring the much-maligned Inspector Lestrade, so the earnest, brave, but slightly dim companion to the great Consulting Detective must surely be worth a series of his own. Ryan takes our beloved physician and puts him down amid the carnage of The Great War. Too old to fight, Watson’s medical expertise is still valuable. In Dead Man’s Land (2013) Watson investigates a murder in the trenches which is due, not to a German bullet or shell, but to something much more sinister, and much closer to home.

Robert Ryan, also known as Tom Neale, is an English author, journalist and screenwriter. He has written a host of successful adventure novels and thrillers, but our microscope focuses on his Dr Watson novels. He is not the first writer to exploit the potential of Sherlockiana, nor will he be the last. M J Trow wrote an entertaining series of books featuring the much-maligned Inspector Lestrade, so the earnest, brave, but slightly dim companion to the great Consulting Detective must surely be worth a series of his own. Ryan takes our beloved physician and puts him down amid the carnage of The Great War. Too old to fight, Watson’s medical expertise is still valuable. In Dead Man’s Land (2013) Watson investigates a murder in the trenches which is due, not to a German bullet or shell, but to something much more sinister, and much closer to home.

The Dead Can Wait followed in 2014, and our man has returned from the trenches, mentally shattered by his experience. He has little time to recuperate however, as he is called to investigate what appears to be a mass killing – in a top secret research facility set up to develop a weapon that will be decisive in ending the war.

2015 brought A Study In Murder, and Watson has mismanaged his life to the extent that he is now in a wintry prisoner of war camp, far behind German lines. It is 1917, and the outcome of the war hangs in the balance. Murder, however, is no respecter of history, and when some poor fellow inmate is murdered, ostensibly for his Red Cross food parcel, Watson smells a sizeable and malodorous rat. January 2016 brought The Sign of Fear. The rather clumsy amalgam of two canonical Sherlock Holmes stories finds the indefatigable Watson once more at home, but a home at the mercy of a new terror – bombing raids from German aircraft. Our man is forced to untangle a mystery involving kidnap and a floating ambulance sunk by a German torpedo.

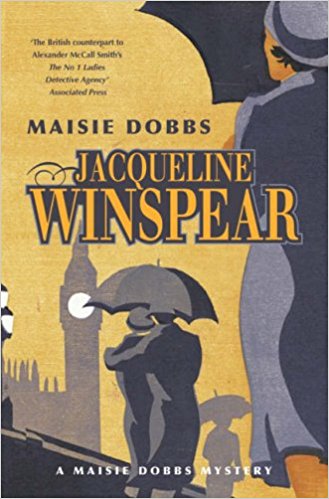

Maisie Dobbs is both the title of a novel by Jacqueline Winspear, and the name of the central character in a series which has now run to twelve novels. In the first of the series we learn that Maisie has seen the worst of The Western Front during her time as a nurse, but now she has returned to an England which is definitely not a land for heroes. She uses her acquaintance with a distinguished French investigator to set up her own agency. Although the series takes Maisie through the years between the wars, right up to the rise of Nazism, the shadow of the dreadful years of The Great War is cast over many of Maisie’s cases. The author herself says:

Maisie Dobbs is both the title of a novel by Jacqueline Winspear, and the name of the central character in a series which has now run to twelve novels. In the first of the series we learn that Maisie has seen the worst of The Western Front during her time as a nurse, but now she has returned to an England which is definitely not a land for heroes. She uses her acquaintance with a distinguished French investigator to set up her own agency. Although the series takes Maisie through the years between the wars, right up to the rise of Nazism, the shadow of the dreadful years of The Great War is cast over many of Maisie’s cases. The author herself says:

“The war and its aftermath provide fertile ground for a mystery. Such great social upheaval allows for the strange and unusual to emerge and a time of intense emotions can, to the writer of fiction, provide ample fodder for a compelling story, especially one concerning criminal acts and issues of guilt and innocence. After all, a generation is said to have lost its innocence in The Great War. The mystery genre provides a wonderful vehicle for exploring such a time,”

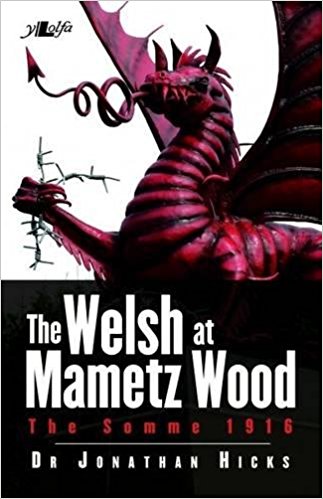

Dr Jonathan Hicks is a Welsh academic with an abiding interest in The Great War, and he has written a graphic and superbly researched history of a battle which was both one of his countrymen’s finest hours, but in terms of loss of life, arguably their darkest. A detailed look at The Welsh at Mametz Wood, The Somme 1916 is outside of our remit here, but its scholarship and interpretation of history is clearly reflected in what was his first fictional Great War novel, The Dead of Mametz (2011). His central character is Captain Thomas Oscendale of the Military Foot Police, and he has a problem to solve. An attractive French widow has been found raped and murdered in a nearby town. In her clenched fingers is a button from a British army tunic. A Welsh NCO, reputedly her lover, has just turned his Lee Enfield rifle on himself after apparently killing two of his colleagues. A mysterious British officer attends the crime scene, but then disappears. As Oscendale tries to unravel the tangle of clues, he finds a map purporting to show a site in the middle of Mametz Wood where a fortune is buried. Blind-sided by German spies and a conspiracy way above his rank, Oscendale must apply his police training to combat corrupt officials, military incompetence and the disdain – bordering on hatred – felt by front-line soldiers for ‘Red Caps’.

Dr Jonathan Hicks is a Welsh academic with an abiding interest in The Great War, and he has written a graphic and superbly researched history of a battle which was both one of his countrymen’s finest hours, but in terms of loss of life, arguably their darkest. A detailed look at The Welsh at Mametz Wood, The Somme 1916 is outside of our remit here, but its scholarship and interpretation of history is clearly reflected in what was his first fictional Great War novel, The Dead of Mametz (2011). His central character is Captain Thomas Oscendale of the Military Foot Police, and he has a problem to solve. An attractive French widow has been found raped and murdered in a nearby town. In her clenched fingers is a button from a British army tunic. A Welsh NCO, reputedly her lover, has just turned his Lee Enfield rifle on himself after apparently killing two of his colleagues. A mysterious British officer attends the crime scene, but then disappears. As Oscendale tries to unravel the tangle of clues, he finds a map purporting to show a site in the middle of Mametz Wood where a fortune is buried. Blind-sided by German spies and a conspiracy way above his rank, Oscendale must apply his police training to combat corrupt officials, military incompetence and the disdain – bordering on hatred – felt by front-line soldiers for ‘Red Caps’.

Oscendale returned in Demons Walk Among Us (2013) and he falls for a beautiful war widow in the process. When he finds that his most likely witness to corruption in high military places has been invalided home with neurasthenia, he has to resort to drastic measures that threaten his own life and sanity. The action takes us from the dust, heat, flies and bloated corpses of 1915 Gallipoli, through the bleak and devastated flatlands of Flanders, to small-town Wales, with its shattered and impoverished war widows, deserters at their wits’ end, and heroes who have been crippled both physically and mentally. One of the strengths of the Oscendale novels is that Hicks combines the horror of The Front Line with less dramatic but equally menacing events back home in Wales.

History. Crime Fiction. Railways. It’s as if Andrew Martin has written a series of books specifically tailored to three of my abiding interests, but within his Jim Stringer, Steam Detective series there is even more icing on the cake – a pair of novels set in The Great War. Jim Stringer is a railwayman through and through, and we first met him as a young man in an intriguing account of The Necropolis Railway, where he investigated shenanigans connected with the funeral trains that used to run from near Waterloo Station out to Brookwood Cemetery in Surrey.

By 1916, however, Stringer has several years of crime detection under his belt, but he is sent to France where he survives the carnage of 1st July, and is picked out to supervise the running of ammunition trains carrying vital supplies up to the front line. The Somme Stations (2012) is both a chilling account of everyday life on The Western Front, but also an excellent murder mystery, with Stringer investigating a criminal death – as opposed to one of the scores of men killed daily by bullets and shells.

By 1916, however, Stringer has several years of crime detection under his belt, but he is sent to France where he survives the carnage of 1st July, and is picked out to supervise the running of ammunition trains carrying vital supplies up to the front line. The Somme Stations (2012) is both a chilling account of everyday life on The Western Front, but also an excellent murder mystery, with Stringer investigating a criminal death – as opposed to one of the scores of men killed daily by bullets and shells.

1917 sees Stringer invalided away from the trenches, but sent out to Mesopotamia to investigate apparent treachery within the British military establishment. In The Baghdad Railway Club (2012) Lieutenant-Colonel Shepherd is said to have accepted a bribe from the fleeing Turks.

Stringer goes undercover as a railway advisor to investigate, but his contact Captain Boyd is discovered murdered in an abandoned station. No further help will be sent, so Stringer is on his own catching the murderer, and preventing a giant betrayal of the British effort. He has to do so whilst navigating an unfamiliar landscape, avoiding getting caught up in an Arab uprising, fighting off a case of malaria during a sweltering Baghdad summer, and treading a careful path as he investigates members of the officer class.

Stringer goes undercover as a railway advisor to investigate, but his contact Captain Boyd is discovered murdered in an abandoned station. No further help will be sent, so Stringer is on his own catching the murderer, and preventing a giant betrayal of the British effort. He has to do so whilst navigating an unfamiliar landscape, avoiding getting caught up in an Arab uprising, fighting off a case of malaria during a sweltering Baghdad summer, and treading a careful path as he investigates members of the officer class.

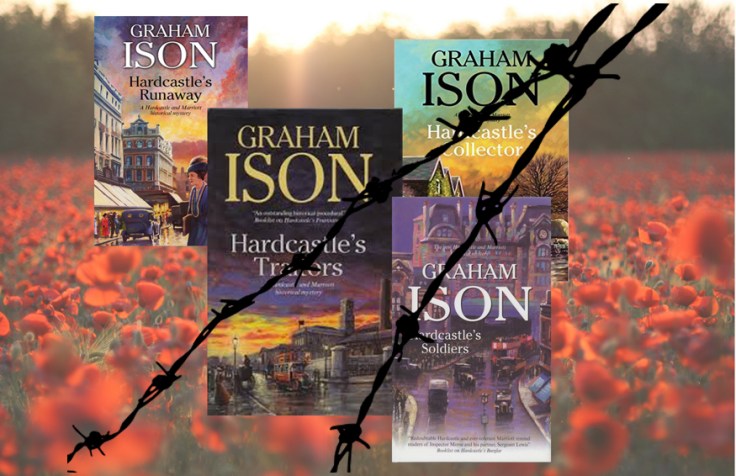

We will finish with the Inspector Hardcastle novels by Graham Ison. In one sense they are well-crafted – but otherwise unremarkable – police procedurals with a period setting, but Ison has created a sequence in the series where criminal events in London are set against successive years of the war. Hardcastle is a bluff, tough, pipe-and-slippers kind of copper, but the novels have a subtle sub-plot which reflects how the war is being fought on the home front, with the inevitable shortage of manpower in the police service, and the ruthless advantage taken by those who live outside of the law. The books have a cosy tinge to them, but are none the worse for that. Ison doesn’t flinch in his portrayal of the effect of a brutal war on hard-pressed families as well as those who are financially more comfortable. For those who like a good London novel, you will find no current writer who is better than Ison at period detail and the creation of an authentic atmosphere.

Some authors save the best for last. Others, like Joseph Heller with Catch 22, produce such a devastatingly good first novel that the rest of their lives are spent trying to better it. Rachel Amphlett has a new novel out – watch out for our review of Scared To Death – but she has taken time out of her hectic schedule to look at a few brilliant ‘first in series’ crime novels.

Some authors save the best for last. Others, like Joseph Heller with Catch 22, produce such a devastatingly good first novel that the rest of their lives are spent trying to better it. Rachel Amphlett has a new novel out – watch out for our review of Scared To Death – but she has taken time out of her hectic schedule to look at a few brilliant ‘first in series’ crime novels. Michael Connelly – The Black Echo (Harry Bosch #1)

Michael Connelly – The Black Echo (Harry Bosch #1) Peter James – Dead Simple (Roy Grace #1)

Peter James – Dead Simple (Roy Grace #1) Angela Marsons – Silent Scream (Kim Stone #1)

Angela Marsons – Silent Scream (Kim Stone #1)

Robert Ryan, also known as Tom Neale, is an English author, journalist and screenwriter. He has written a host of successful adventure novels and thrillers, but our microscope focuses on his Dr Watson novels. He is not the first writer to exploit the potential of Sherlockiana, nor will he be the last. M J Trow wrote an entertaining series of books featuring the much-maligned Inspector Lestrade, so the earnest, brave, but slightly dim companion to the great Consulting Detective must surely be worth a series of his own. Ryan takes our beloved physician and puts him down amid the carnage of The Great War. Too old to fight, Watson’s medical expertise is still valuable.

Robert Ryan, also known as Tom Neale, is an English author, journalist and screenwriter. He has written a host of successful adventure novels and thrillers, but our microscope focuses on his Dr Watson novels. He is not the first writer to exploit the potential of Sherlockiana, nor will he be the last. M J Trow wrote an entertaining series of books featuring the much-maligned Inspector Lestrade, so the earnest, brave, but slightly dim companion to the great Consulting Detective must surely be worth a series of his own. Ryan takes our beloved physician and puts him down amid the carnage of The Great War. Too old to fight, Watson’s medical expertise is still valuable.

Maisie Dobbs

Maisie Dobbs  Dr Jonathan Hicks is a Welsh academic with an abiding interest in The Great War, and he has written a graphic and superbly researched history of a battle which was both one of his countrymen’s finest hours, but in terms of loss of life, arguably their darkest. A detailed look at

Dr Jonathan Hicks is a Welsh academic with an abiding interest in The Great War, and he has written a graphic and superbly researched history of a battle which was both one of his countrymen’s finest hours, but in terms of loss of life, arguably their darkest. A detailed look at

By 1916, however, Stringer has several years of crime detection under his belt, but he is sent to France where he survives the carnage of 1st July, and is picked out to supervise the running of ammunition trains carrying vital supplies up to the front line.

By 1916, however, Stringer has several years of crime detection under his belt, but he is sent to France where he survives the carnage of 1st July, and is picked out to supervise the running of ammunition trains carrying vital supplies up to the front line.  Stringer goes undercover as a railway advisor to investigate, but his contact Captain Boyd is discovered murdered in an abandoned station. No further help will be sent, so Stringer is on his own catching the murderer, and preventing a giant betrayal of the British effort. He has to do so whilst navigating an unfamiliar landscape, avoiding getting caught up in an Arab uprising, fighting off a case of malaria during a sweltering Baghdad summer, and treading a careful path as he investigates members of the officer class.

Stringer goes undercover as a railway advisor to investigate, but his contact Captain Boyd is discovered murdered in an abandoned station. No further help will be sent, so Stringer is on his own catching the murderer, and preventing a giant betrayal of the British effort. He has to do so whilst navigating an unfamiliar landscape, avoiding getting caught up in an Arab uprising, fighting off a case of malaria during a sweltering Baghdad summer, and treading a careful path as he investigates members of the officer class.

and a recurring – and malign – character named The Peacemaker looms over proceedings. The books work very well as detective stories, and Perry has years of experience at blending crime with period settings. She has been careful to put each plotline in the context of the big events of each year; No Graves As Yet, for example, sets us down in the elegaic final summer of peace, in an England which was still Edwardian in spirit despite the old King being four years gone; in Shoulder The Sky Reavley searches for the killer of a war correspondent whose honesty made him a marked man, and his quest for answers takes him from one military debacle to another, in this case from Ypres to Gallipoli. Perry writes with great conviction and, as with her other books, mixes intrigue, adventure, high drama and impeccable period detail.

and a recurring – and malign – character named The Peacemaker looms over proceedings. The books work very well as detective stories, and Perry has years of experience at blending crime with period settings. She has been careful to put each plotline in the context of the big events of each year; No Graves As Yet, for example, sets us down in the elegaic final summer of peace, in an England which was still Edwardian in spirit despite the old King being four years gone; in Shoulder The Sky Reavley searches for the killer of a war correspondent whose honesty made him a marked man, and his quest for answers takes him from one military debacle to another, in this case from Ypres to Gallipoli. Perry writes with great conviction and, as with her other books, mixes intrigue, adventure, high drama and impeccable period detail. The First Casualty (2005), saw stand-up comedian Ben Elton continuing a not-altogether-successful foray into the world of serious fiction. He is to be commended for placing a largely unsympathetic character at the centre of his story, but the misadventures of Douglas Kingsley, a career policeman but now a conscientious objector, tend to involve issues such as homosexuality, feminism, pacifism and the Irish Question, which were more on people’s lips at the time of Elton’s TV fame than during the period of WWI itself. Kingsley is thrown in jail because of his stance on the war, and is then abused by criminals who attribute their incarceration to his devotion to duty as a copper. The apparent murder of a rebellious soldier poet (a thinly disguised Siegfried Sassoon) and the sexual misdeeds of his wife Agnes give Kingsley plenty to think about.

The First Casualty (2005), saw stand-up comedian Ben Elton continuing a not-altogether-successful foray into the world of serious fiction. He is to be commended for placing a largely unsympathetic character at the centre of his story, but the misadventures of Douglas Kingsley, a career policeman but now a conscientious objector, tend to involve issues such as homosexuality, feminism, pacifism and the Irish Question, which were more on people’s lips at the time of Elton’s TV fame than during the period of WWI itself. Kingsley is thrown in jail because of his stance on the war, and is then abused by criminals who attribute their incarceration to his devotion to duty as a copper. The apparent murder of a rebellious soldier poet (a thinly disguised Siegfried Sassoon) and the sexual misdeeds of his wife Agnes give Kingsley plenty to think about. Rennie Airth has written a series of novels featuring a retired policeman and WWI veteran, John Madden. I am giving these an honorary mention, as Madden’s whole approach to life, his attitude towards detection, and his views on criminality are all profoundly influenced by his experience in the trenches, and when Manning is centre stage, his musings frequently recall his wartime experiences. The first of the series is River of Darkness (1999), and the events take place in 1921, when men were still dying of war wounds, and many of the country’s war memorials had still to be dedicated. Madden has returned from the war and is now a top detective with Scotland Yard. He is called down to investigate a savage multiple murder in rural Surrey, and he becomes convinced that the brutality of the killings is linked to events that happened during the war, and that the perpetrator, like Madden himself, has been left with scars that are both physical and mental. You might like to read the Fully Booked review of a later John Madden novel,

Rennie Airth has written a series of novels featuring a retired policeman and WWI veteran, John Madden. I am giving these an honorary mention, as Madden’s whole approach to life, his attitude towards detection, and his views on criminality are all profoundly influenced by his experience in the trenches, and when Manning is centre stage, his musings frequently recall his wartime experiences. The first of the series is River of Darkness (1999), and the events take place in 1921, when men were still dying of war wounds, and many of the country’s war memorials had still to be dedicated. Madden has returned from the war and is now a top detective with Scotland Yard. He is called down to investigate a savage multiple murder in rural Surrey, and he becomes convinced that the brutality of the killings is linked to events that happened during the war, and that the perpetrator, like Madden himself, has been left with scars that are both physical and mental. You might like to read the Fully Booked review of a later John Madden novel,  Bess Crawford, who manages to combine the grim task of being a nurse tending to the appalling violence inflicted upon the bodies of young men fighting in the trenches, with a determination to get to the bottom of various mysteries which have more to do with individual human failings than with the inexorable mincing machine of the war. Her investigations are sometimes within sound of German guns, but also nearer home, such as in An Unwilling Accomplice (2014), when she has to accompany a celebrity wounded soldier to Buckingham Palace to receive a gallantry award, only to have him escape his wheelchair and commit a savage murder. The Todds have also invested time and words to bring to life the character of Detective Inspector Ian Rutledge, a man who suspended his police career to fight for King and Country. He returns to the police force after the war, but finds that the blood-soaked years have left a bitter legacy, such as in A Lonely Death (2011), when he is called to investigate a series of killings in a Sussex village, and finds that the deaths are all connected with the wartime service of the victims.

Bess Crawford, who manages to combine the grim task of being a nurse tending to the appalling violence inflicted upon the bodies of young men fighting in the trenches, with a determination to get to the bottom of various mysteries which have more to do with individual human failings than with the inexorable mincing machine of the war. Her investigations are sometimes within sound of German guns, but also nearer home, such as in An Unwilling Accomplice (2014), when she has to accompany a celebrity wounded soldier to Buckingham Palace to receive a gallantry award, only to have him escape his wheelchair and commit a savage murder. The Todds have also invested time and words to bring to life the character of Detective Inspector Ian Rutledge, a man who suspended his police career to fight for King and Country. He returns to the police force after the war, but finds that the blood-soaked years have left a bitter legacy, such as in A Lonely Death (2011), when he is called to investigate a series of killings in a Sussex village, and finds that the deaths are all connected with the wartime service of the victims. I’ll conclude this first part of the feature with a quick glimpse at a trio of curiosities, where the novel gives a fleeting but significant nod to The Great War. In 1917, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle published a collection of Holmes stories dating back across the first years of the century. In the concluding story His Last Bow: an epilogue of Sherlock Holmes, the great man disposes of a particularly dastardly German spy, and as the story finishes, he says,

I’ll conclude this first part of the feature with a quick glimpse at a trio of curiosities, where the novel gives a fleeting but significant nod to The Great War. In 1917, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle published a collection of Holmes stories dating back across the first years of the century. In the concluding story His Last Bow: an epilogue of Sherlock Holmes, the great man disposes of a particularly dastardly German spy, and as the story finishes, he says,

Anthony Price has written many spy thrillers tinged with elements of military history, and in Other Paths To Glory (1974) he uses abandoned German fortifications deep beneath the French countryside as the central feature of the novel, most of which is set in the present day world of international realpolitik. As the bunkers in the novel are set in the Somme region, it is highly likely that they are modeled on the astonishing engineering of The Schwaben Redoubt, near Thiepval. The Redoubt was one of the most impregnable defences on The Western front, and it cost many thousands of lives before it was finally taken. The book is the fifth in the series featuring Dr David Audley and Colonel Jack Butler,

Anthony Price has written many spy thrillers tinged with elements of military history, and in Other Paths To Glory (1974) he uses abandoned German fortifications deep beneath the French countryside as the central feature of the novel, most of which is set in the present day world of international realpolitik. As the bunkers in the novel are set in the Somme region, it is highly likely that they are modeled on the astonishing engineering of The Schwaben Redoubt, near Thiepval. The Redoubt was one of the most impregnable defences on The Western front, and it cost many thousands of lives before it was finally taken. The book is the fifth in the series featuring Dr David Audley and Colonel Jack Butler,

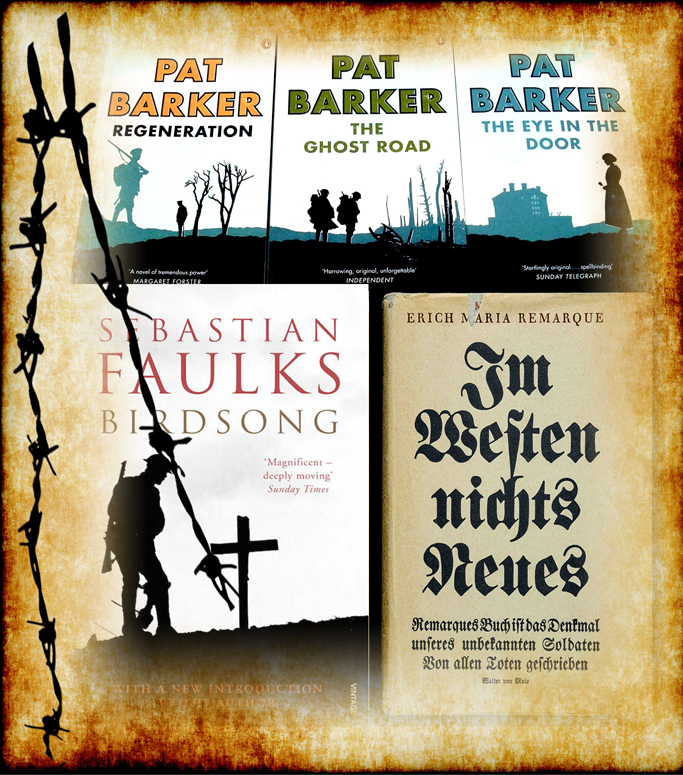

What needs to be held up like a bright lantern in our search for good WWI crime fiction, is the fact that those six years are like no other in British history. They have produced a mythology which is unique in modern memory, and with it a collection of tropes, images, phrases and conventions, all of which find their way into the consciousness of writers and readers. Military historians tell only part of the story: the Alan Clark theory of The Donkeys and the anti-war polemic of the the 1960s and 70s has one version of events; more recent accounts of the war by revisionist historians such as John Terrain and Gary Sheffield tell another tale altogether. In considering books and writers for this feature I have used two criteria. Firstly, there must be crime involved that is distinct from the licensed slaughter of wartime and, secondly, the events of the war must cast their shadows over the narrative either in a contemporary sense or in the form of a social or political legacy.

What needs to be held up like a bright lantern in our search for good WWI crime fiction, is the fact that those six years are like no other in British history. They have produced a mythology which is unique in modern memory, and with it a collection of tropes, images, phrases and conventions, all of which find their way into the consciousness of writers and readers. Military historians tell only part of the story: the Alan Clark theory of The Donkeys and the anti-war polemic of the the 1960s and 70s has one version of events; more recent accounts of the war by revisionist historians such as John Terrain and Gary Sheffield tell another tale altogether. In considering books and writers for this feature I have used two criteria. Firstly, there must be crime involved that is distinct from the licensed slaughter of wartime and, secondly, the events of the war must cast their shadows over the narrative either in a contemporary sense or in the form of a social or political legacy.

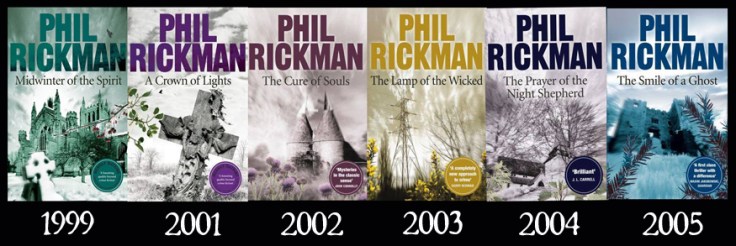

The Reverend Merrily Watkins, who was first brought to life by Phil Rickman in The Wine of Angels in 1998, is, on one level, your average workaday Anglican parish priest. For starters she is a woman, and the Church’s own website tells us that while male ordinations are declining, those of women are increasing rapidly. Secondly, Merrily faces a declining congregation in her Herefordshire village – just like hundreds of other parishes up and down the country. Thirdly, she observes – at a distance, admittedly – the continuing friction between modernising progressives and the traditionalists in the hierarchy of the Church of England.

The Reverend Merrily Watkins, who was first brought to life by Phil Rickman in The Wine of Angels in 1998, is, on one level, your average workaday Anglican parish priest. For starters she is a woman, and the Church’s own website tells us that while male ordinations are declining, those of women are increasing rapidly. Secondly, Merrily faces a declining congregation in her Herefordshire village – just like hundreds of other parishes up and down the country. Thirdly, she observes – at a distance, admittedly – the continuing friction between modernising progressives and the traditionalists in the hierarchy of the Church of England.

Philip Kerr’s Bernie Gunther novels bestride the 20th century, from the rise of the Nazis in 1930s Germany to the post war period when many countries still sheltered mysterious German gentlemen whose collective past has been, of necessity, reinvented. Gunther is a smart talking, smart thinking policeman who has kept his sanity intact – but his conscience rather less so – by dealing with such elemental forces as Reinhardt Heydrich, Joseph Goebbels, Juan and Evita Peron, and Adolf Eichmann.

Philip Kerr’s Bernie Gunther novels bestride the 20th century, from the rise of the Nazis in 1930s Germany to the post war period when many countries still sheltered mysterious German gentlemen whose collective past has been, of necessity, reinvented. Gunther is a smart talking, smart thinking policeman who has kept his sanity intact – but his conscience rather less so – by dealing with such elemental forces as Reinhardt Heydrich, Joseph Goebbels, Juan and Evita Peron, and Adolf Eichmann. A Man Without Breath (2013) sees Gunther is working for an organisation whose very existence may seem improbable, given the historical context, but Die Wehrmacht Untersuchungsstelle (Wehrmacht Bureau of War Crimes) was set up in 1939 and continued its work until 1945. In 1943, on a mission from the Minister for Propaganda, Joseph Goebbels, Gunther is sent to Smolensk and entrusted with proving that the thousands of corpses lying frozen beneath the trees of the nearby Katyn Forest are those of Polish army officers and intellectuals murdered by the Russian NKVD, and not those of Jews murdered by the SS.

A Man Without Breath (2013) sees Gunther is working for an organisation whose very existence may seem improbable, given the historical context, but Die Wehrmacht Untersuchungsstelle (Wehrmacht Bureau of War Crimes) was set up in 1939 and continued its work until 1945. In 1943, on a mission from the Minister for Propaganda, Joseph Goebbels, Gunther is sent to Smolensk and entrusted with proving that the thousands of corpses lying frozen beneath the trees of the nearby Katyn Forest are those of Polish army officers and intellectuals murdered by the Russian NKVD, and not those of Jews murdered by the SS. the German military that Hitler is a dangerous upstart who has already damaged the country beyond repair, and must be stopped. Adrift on a sea of violent corruption, Gunther constantly plays the role of the decent man, but in the end, he follows one theology, and one theology only. If he wakes up the next day with his head firmly attached to his shoulders, and has feeling in his extremities, then he has done the right thing. His conscience has not died, but it is far from well; it competes a whole chorale of competing voices in his head, each wishing to be heard. As he is left helpless by the world of spin and disinformation orchestrated by Dr Goebbels, (right) he must resort to his basic copper’s instincts to protect himself and uncover the truth.

the German military that Hitler is a dangerous upstart who has already damaged the country beyond repair, and must be stopped. Adrift on a sea of violent corruption, Gunther constantly plays the role of the decent man, but in the end, he follows one theology, and one theology only. If he wakes up the next day with his head firmly attached to his shoulders, and has feeling in his extremities, then he has done the right thing. His conscience has not died, but it is far from well; it competes a whole chorale of competing voices in his head, each wishing to be heard. As he is left helpless by the world of spin and disinformation orchestrated by Dr Goebbels, (right) he must resort to his basic copper’s instincts to protect himself and uncover the truth.