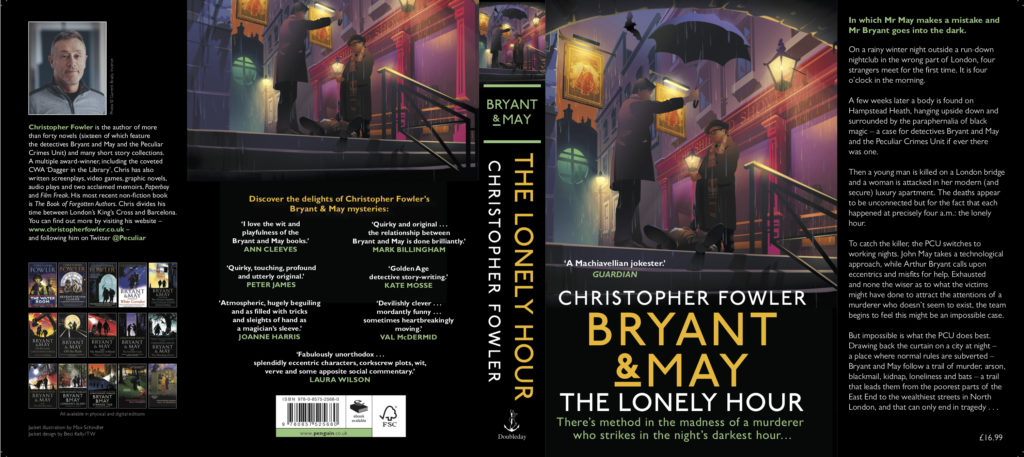

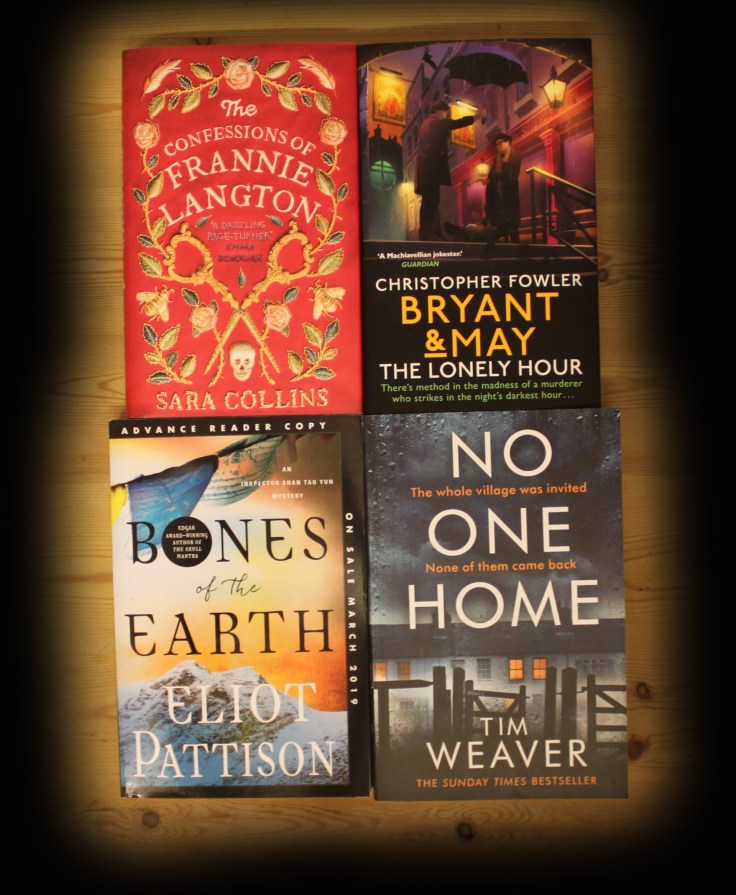

The impossibly geriatric constabulary codgers Arthur Bryant and John May return for another journey into London’s darkside in pursuit of those who kill. This time, the killer appears to be armed with a trocar – an obscure but deadly surgical instrument originally intended to penetrate the body allowing gases or fluid to escape. From the undergrowth of a copse on Hampstead Heath, and the unforgiving undertow of the Thames, via an exclusive multi-story apartment complex, to the pedestrian walkway of a Thames bridge, the victims seems to have nothing in common except the time of their demise – the deadly hour of 4.00 am.

Bryant and May – and the rest of the Peculiar Crimes Unit – have been threatened with closure before, but this time their impatient and disapproving police bosses mean business. The PCU, both collectively and individually flounder around trying to work out what connects the corpses, and who is expertly wielding the trocar. Like Andrew Marvell’s ‘Time’s Winged Chariot’, the accountants and political schemers of the Metropolitan Police are ‘hurrying near’, and failure to catch this killer will certainly mean that the shambolic HQ of the Peculiar Crimes Unit on Caledonian Road will soon be in need of new tenants.

Bryant and May – and the rest of the Peculiar Crimes Unit – have been threatened with closure before, but this time their impatient and disapproving police bosses mean business. The PCU, both collectively and individually flounder around trying to work out what connects the corpses, and who is expertly wielding the trocar. Like Andrew Marvell’s ‘Time’s Winged Chariot’, the accountants and political schemers of the Metropolitan Police are ‘hurrying near’, and failure to catch this killer will certainly mean that the shambolic HQ of the Peculiar Crimes Unit on Caledonian Road will soon be in need of new tenants.

Don’t be misled by the jokes, delightful cultural references, and Arthur’s frequent put-downs of the PCU’s hapless boss, most of which go over Raymond Land’s head but, fortunately, not ours. Physicists will probably say that their world has different rules, but in literature light can only exist relative to darkness, and Fowler does not allow the chiffon gaiety within the Peculiar Crimes Unit to disguise a dystopian London woven from a much darker thread. He says:

“Approaching midnight, the black and grey striped concourse of King’s Cross Station remained almost as busy as it had been during the day. Some Italian students appeared to be having a picnic under the station canopy. A homeless girl ms on her knees next to a lengthy cardboard message explaining her circumstances. A Jamaican family dressed in home-made ecclesiastical vestments were warning everyone that hell awaited sinners. A phalanx of bachelorettes in tiny silver dresses, strappy shoes and bunny ears marched past, heading to their next destination like soldiers on a final tour of duty. Inside the station, tourists were still lurking round the Harry Potter trolley that had been originally set there as a joke by the station guards, then monetized when queues appeared. As flinty-eyed and mean as it had ever been, London was good at making everyone pay.”

If a better paragraph about London has been written in recent years, I have yet to read it

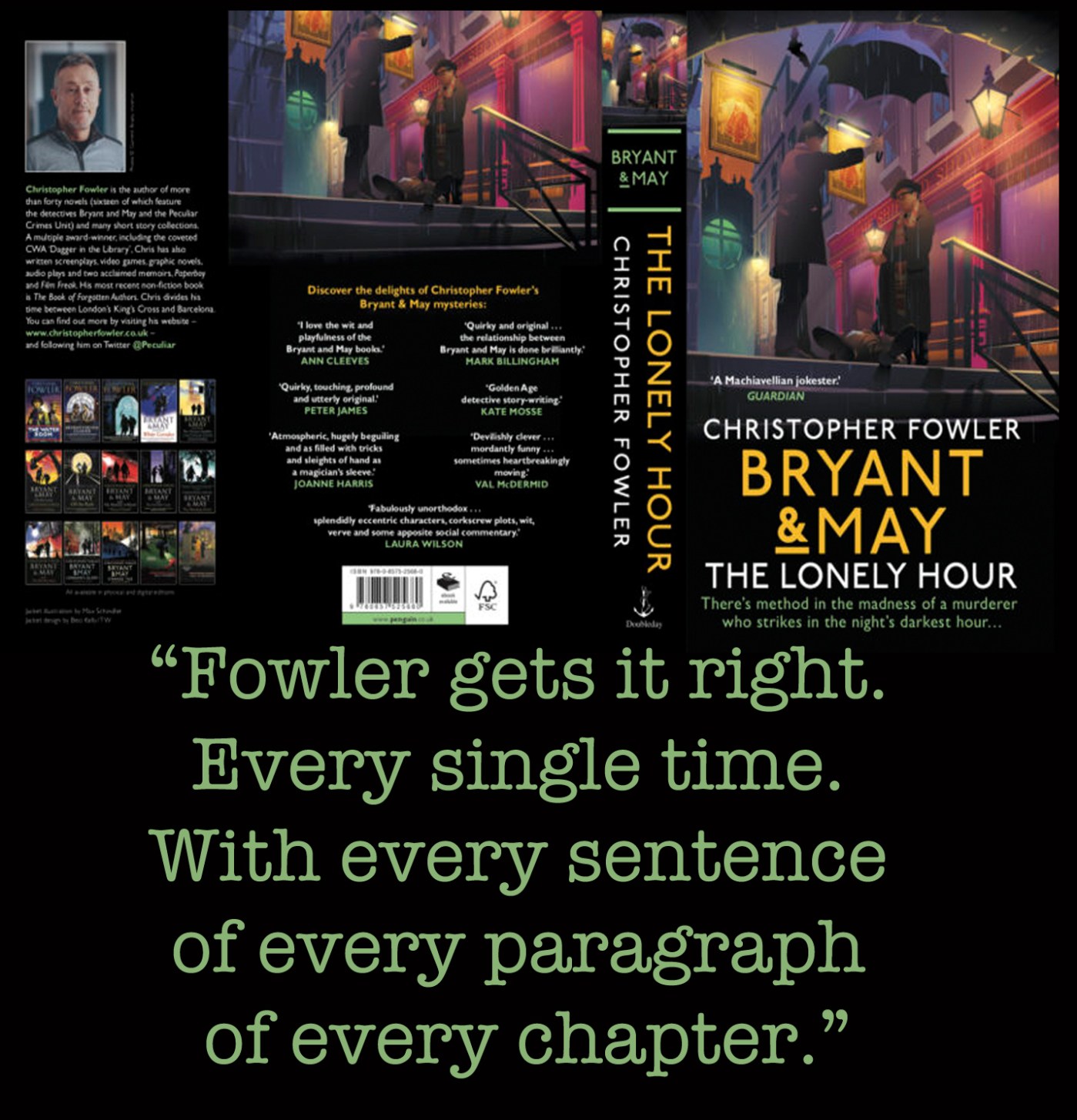

Fowler’s London is a place where the same streets, courtyards, alleys and highways have been walked for centuries; Roman legionaries, Norman functionaries, medieval merchants, Tudor politicians, Restoration poets, Georgian gamblers, Victorian philanthropists, Great War Tommies, and now City spivs with their dreams and nightmares spinning about in front of them on their smartphones – all have played their part in treading history down beneath their feet into a compressed and powerful seam of memory. This memory, whether they know it or not, affects the lives of those who live, work, lust, learn and – ultimately – die in London. Other writers, notably Peter Ackroyd, have been drawn to this lodestone and tapped into its power. Some authors have taken up the theme but befuddled readers with too much arcane psychogeography. Fowler gets it right. Every single time. With every sentence of every paragraph of every chapter.

Bryant is neither Mr Pastry, Charles Pooter nor Mr Bean. He is as sharp as a tack despite such running gags as his coat pockets being full of fluff covered boiled sweets long since disappeared from English shelves. If we knew no better, we might describe him as having a personality disorder somewhere on the autism spectrum, but there are precious moments in The Lonely Hour where the old man brings himself up short with the realisation that he is, most of the time, chronically selfish.

Thanks to Bryant’s genius, the mystery is solved and the killer brought to justice, but these are certainly the grimmest days ever for the PCU, and as this brilliantly entertaining story reaches its conclusion, Fowler (right) slowly but irrevocably turns the tap marked Darkness to its fully open position. The Lonely Hour is published by Doubleday and is out now.

Thanks to Bryant’s genius, the mystery is solved and the killer brought to justice, but these are certainly the grimmest days ever for the PCU, and as this brilliantly entertaining story reaches its conclusion, Fowler (right) slowly but irrevocably turns the tap marked Darkness to its fully open position. The Lonely Hour is published by Doubleday and is out now.

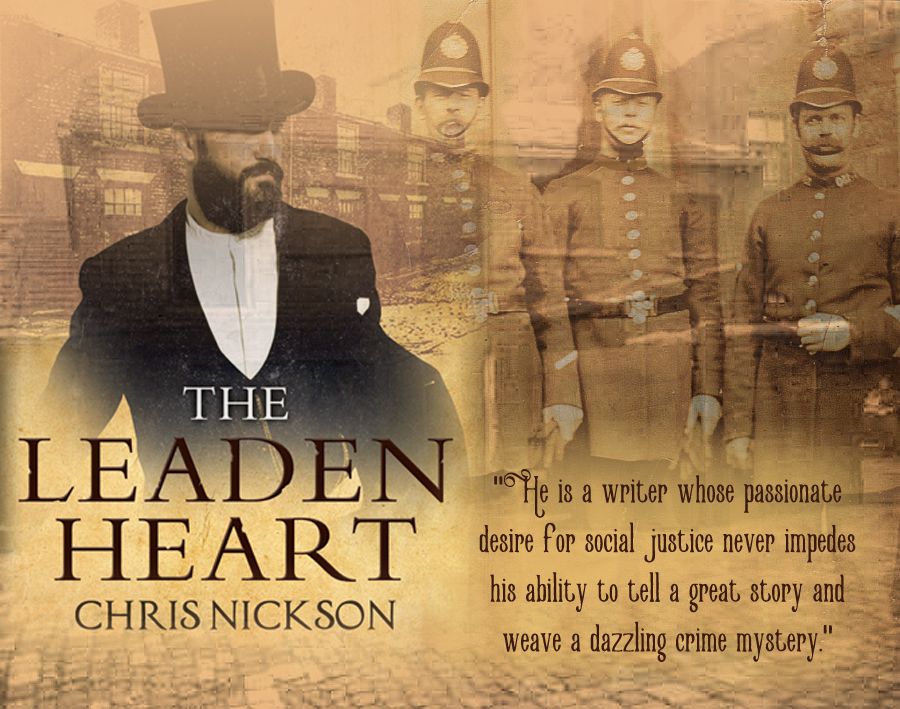

Harper lives above a city pub, the Victoria. His wife, Annabelle, is the landlady, but she is also a fiercely determined advocate of women’s rights, and she has made waves by being elected to the local Board of Guardians, a largely male-dominated organisation which is tasked with administering what, in the dying years of Queen Victoria’s reign, passed for social care. When the brother of Harper’s one-time colleague, Billy Reed, commits suicide the death is dismissed, albeit sadly, as commonplace, but Reed believes that his brother’s death is due to something more sinister, and he asks Harper to investigate.

Harper lives above a city pub, the Victoria. His wife, Annabelle, is the landlady, but she is also a fiercely determined advocate of women’s rights, and she has made waves by being elected to the local Board of Guardians, a largely male-dominated organisation which is tasked with administering what, in the dying years of Queen Victoria’s reign, passed for social care. When the brother of Harper’s one-time colleague, Billy Reed, commits suicide the death is dismissed, albeit sadly, as commonplace, but Reed believes that his brother’s death is due to something more sinister, and he asks Harper to investigate.

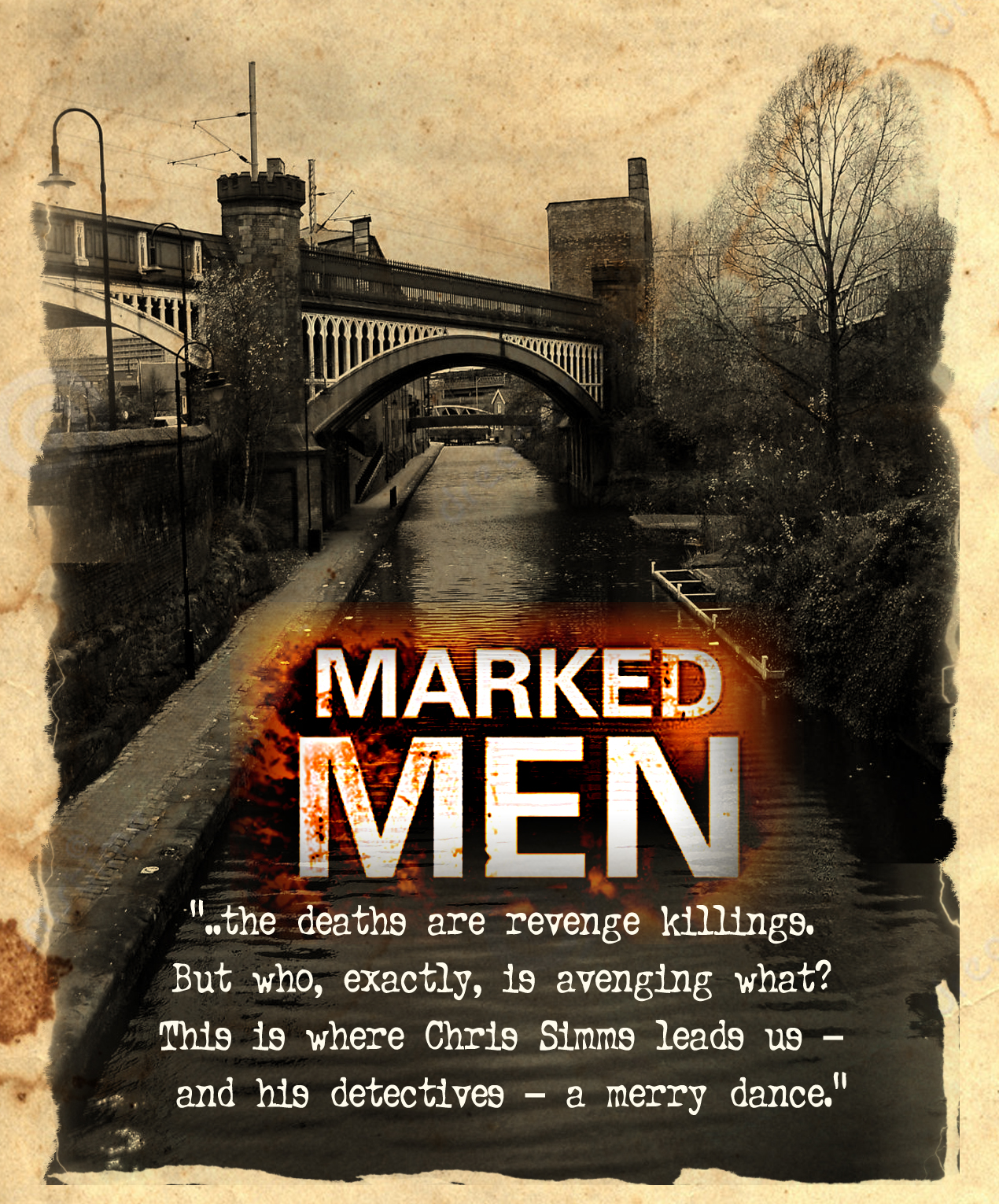

Marked Men begins on an idyllic Spanish beach, but then switches to the less salubrious setting of urban Manchester, and we only learn the significance of the opening much later in the plot. This way of starting a novel has become rather well-worn, but Simms handles it well and times to perfection the revelation of its significance. The Manchester action begins with Blake in waders and hard hat at the bottom of a drained lock on a local canal. There is a body, naturally, with more to follow, and as Blake and his immediate boss, DS Dragomir criss-cross the city trying to make sense of the crime scenes we – like them – are drawn into thinking that the deaths are revenge killings. But who, exactly, is avenging what? This is where Chris Simms leads us – and his detectives – a merry dance. There is a clue, but I have to confess I didn’t get it any quicker than did Blake and Dragomir.

Marked Men begins on an idyllic Spanish beach, but then switches to the less salubrious setting of urban Manchester, and we only learn the significance of the opening much later in the plot. This way of starting a novel has become rather well-worn, but Simms handles it well and times to perfection the revelation of its significance. The Manchester action begins with Blake in waders and hard hat at the bottom of a drained lock on a local canal. There is a body, naturally, with more to follow, and as Blake and his immediate boss, DS Dragomir criss-cross the city trying to make sense of the crime scenes we – like them – are drawn into thinking that the deaths are revenge killings. But who, exactly, is avenging what? This is where Chris Simms leads us – and his detectives – a merry dance. There is a clue, but I have to confess I didn’t get it any quicker than did Blake and Dragomir.

I would be lying if I said I hadn’t been counting the days until this arrived. Kerry Hood at Hodder & Stoughton is to be commended for showing great patience in the face of my impatience, but it finally arrived. Kerry had mentioned that it might be something special, but then publicists always say that, don’t they? So, ripping off the sturdy cardboard wrapper ….

I would be lying if I said I hadn’t been counting the days until this arrived. Kerry Hood at Hodder & Stoughton is to be commended for showing great patience in the face of my impatience, but it finally arrived. Kerry had mentioned that it might be something special, but then publicists always say that, don’t they? So, ripping off the sturdy cardboard wrapper ….

Ta-da! And there it was, the long awaited latest journey into the darkness of men and angels for the Maine PI, Charlie Parker. The adjectives are easy – haunted, conflicted, convincing, troubled, angry, brave … fans of the series can play their own ‘describe Charlie Parker’ game, but most importantly, our man is back.

Ta-da! And there it was, the long awaited latest journey into the darkness of men and angels for the Maine PI, Charlie Parker. The adjectives are easy – haunted, conflicted, convincing, troubled, angry, brave … fans of the series can play their own ‘describe Charlie Parker’ game, but most importantly, our man is back.

Charlie Parker is back, and how! I was advised that I might want to set aside a fair amount of time to read A Book of Bones but, blimey, Kerry was not wrong. At a little short of 700 pages, and weighing nearly 2lbs in old money, the book is certainly a big ‘un. New readers shouldn’t be daunted, though. John Connolly couldn’t write a dull sentence even if he went off to his Alma Mater, Trinity College Dublin, to do a doctorate in dullness.

Charlie Parker is back, and how! I was advised that I might want to set aside a fair amount of time to read A Book of Bones but, blimey, Kerry was not wrong. At a little short of 700 pages, and weighing nearly 2lbs in old money, the book is certainly a big ‘un. New readers shouldn’t be daunted, though. John Connolly couldn’t write a dull sentence even if he went off to his Alma Mater, Trinity College Dublin, to do a doctorate in dullness.

But there was more! Book publicists are an inventive lot, and over the years I’ve had packets of sweets, tiny vials of perfume, books wrapped in funereal paper and black ribbon, facsimiles of detective case files – but never a jigsaw. Wrapped up in a cellophane packet with a lovely Charlie Parker 20 year anniversary graphic were the pieces.

But there was more! Book publicists are an inventive lot, and over the years I’ve had packets of sweets, tiny vials of perfume, books wrapped in funereal paper and black ribbon, facsimiles of detective case files – but never a jigsaw. Wrapped up in a cellophane packet with a lovely Charlie Parker 20 year anniversary graphic were the pieces.

As I was always told to do by my old mum, I isolated the bits with the straight edges first. There was clearly a written message in there, set against the lovely – but sinister – stained glass background. Confession time; although the puzzle didn’t have too many pieces, I got stuck. Fortunately, Mrs P was taking a very rare day off work with a flu bug, and as she is a jigsaw ace, she finished it off for me.

As I was always told to do by my old mum, I isolated the bits with the straight edges first. There was clearly a written message in there, set against the lovely – but sinister – stained glass background. Confession time; although the puzzle didn’t have too many pieces, I got stuck. Fortunately, Mrs P was taking a very rare day off work with a flu bug, and as she is a jigsaw ace, she finished it off for me.

Norway’s Samuel Bjork ticks the boxes with his Olso cops Holger Munch and Mia Krüger. Munch is a bearded bear of a man, overweight and stuffed into his habitual duffel coat like a fat foot into a shoe two sizes too small. His home life is in disarray. Separated from his wife, his daughter Miriam recovering from a serious injury, he seems to treat those people with – at best – edgy tolerance, but his obsession is with the job, and catching criminals. Krüger’s back story makes Munch’s people look like candidates for a TV breakfast cereal advert emphasising warm family values. The story opens with her recovering from – in no particular order – alcoholism, a fatal shoot-out after which she was accused of murder, and the haunting death of her sister, victim of Oslo’s drug scene.

Norway’s Samuel Bjork ticks the boxes with his Olso cops Holger Munch and Mia Krüger. Munch is a bearded bear of a man, overweight and stuffed into his habitual duffel coat like a fat foot into a shoe two sizes too small. His home life is in disarray. Separated from his wife, his daughter Miriam recovering from a serious injury, he seems to treat those people with – at best – edgy tolerance, but his obsession is with the job, and catching criminals. Krüger’s back story makes Munch’s people look like candidates for a TV breakfast cereal advert emphasising warm family values. The story opens with her recovering from – in no particular order – alcoholism, a fatal shoot-out after which she was accused of murder, and the haunting death of her sister, victim of Oslo’s drug scene.

JO BAKER was born and raised in Lancashire, and was educated at Queen Elizabeth School, Kirkby Lonsdale, and Somerville College, Oxford. The Body Lies is her seventh novel, and her best-seller Longbourn is a highly individual reshaping of Pride and Prejudice as seen through the eyes of the “below stairs” staff in the Bennet house. Jo Baker has

JO BAKER was born and raised in Lancashire, and was educated at Queen Elizabeth School, Kirkby Lonsdale, and Somerville College, Oxford. The Body Lies is her seventh novel, and her best-seller Longbourn is a highly individual reshaping of Pride and Prejudice as seen through the eyes of the “below stairs” staff in the Bennet house. Jo Baker has TINA BEATTIE was born in 1955 in Lusaka, Zambia. Her parents were economic migrants from post-war Scotland. She is now Professor of Catholic Studies at the University of Roehampton in London, and has written widely on theology and the Roman Catholic faith. Her writing, particularly with regard to women’s rights and feminism have often brought her into conflict with the more conservative wing of her church. Her Amazon page is

TINA BEATTIE was born in 1955 in Lusaka, Zambia. Her parents were economic migrants from post-war Scotland. She is now Professor of Catholic Studies at the University of Roehampton in London, and has written widely on theology and the Roman Catholic faith. Her writing, particularly with regard to women’s rights and feminism have often brought her into conflict with the more conservative wing of her church. Her Amazon page is MP MILES is from a small town in Dorset.

MP MILES is from a small town in Dorset.