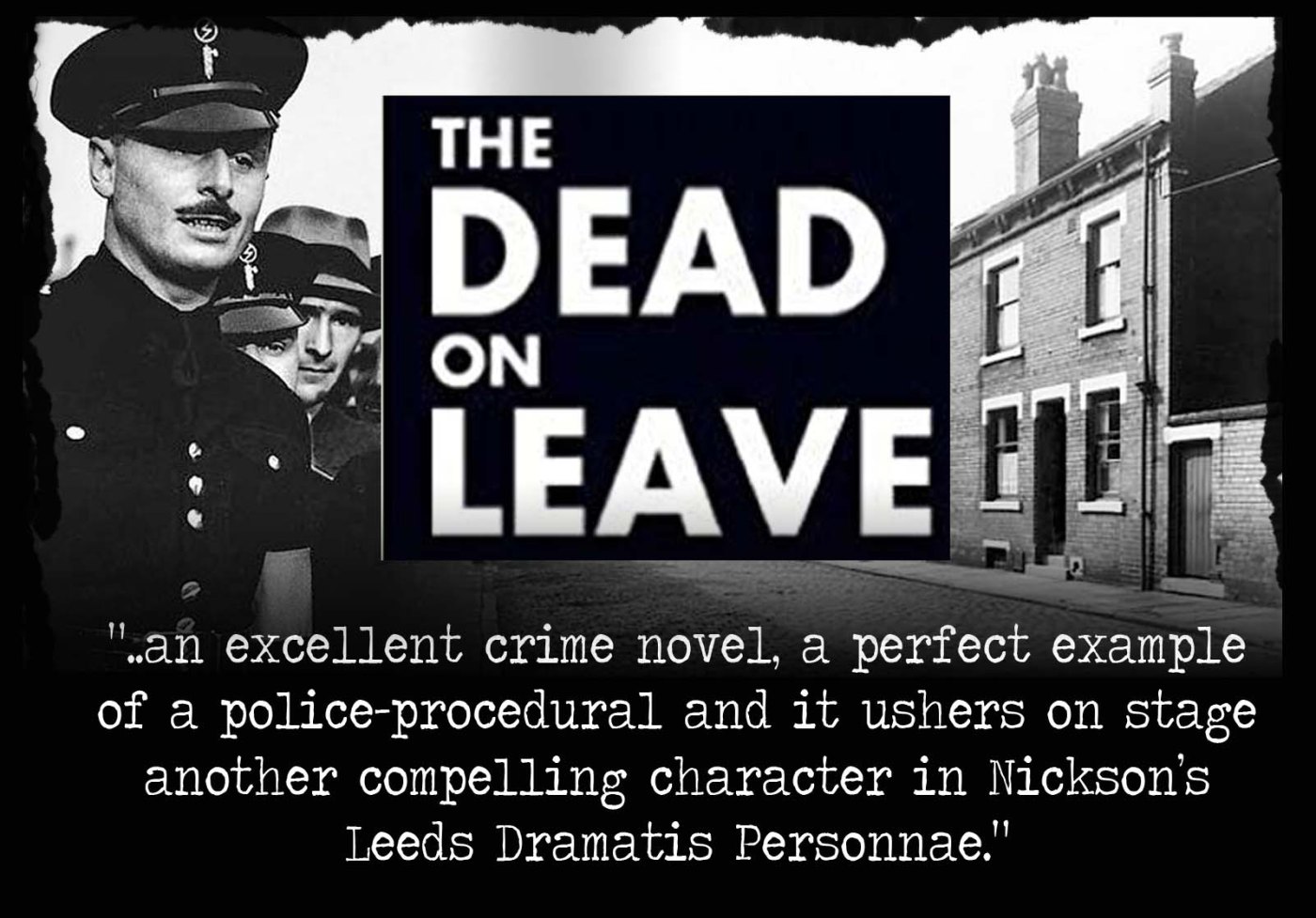

Leeds, Yorkshire. 1936. The once thunderous clatter of its mills and factories is now a hesitant stutter. Although the Great Depression is over, like the plague passing over biblical Egypt it has left many victims. Work is scarce, and men live in fear of being unable to put bread on the table for their wives and children. There is state relief, but it is a grudging pittance. When a widely disliked Means Test Inspector – a man paid to snoop around people’s houses rooting out efforts to cheat the system – is found garotted, there are few to mourn him. But murder is murder, and police detective Urban Raven must find the killer.

It appears the dead man is a would-be follower of Sir Oswald Mosley, charismatic leader of the British Union of Fascists and, after an appearance in Leeds by Mosley and his Blackshirts turns into a riot, it is tempting for the police to think that the murder is politically inspired. As Raven tries to make sense of the killing, he has his own demons to face. Like many other Yorkshiremen, Raven is a Great War veteran, even though his war was brief and horrific. Only able to see active service in the dog-days of the conflict, he was unlucky enough to be close to a fuel dump which was hit by a stray shell. There’s a line from a song about that war, which goes,

It appears the dead man is a would-be follower of Sir Oswald Mosley, charismatic leader of the British Union of Fascists and, after an appearance in Leeds by Mosley and his Blackshirts turns into a riot, it is tempting for the police to think that the murder is politically inspired. As Raven tries to make sense of the killing, he has his own demons to face. Like many other Yorkshiremen, Raven is a Great War veteran, even though his war was brief and horrific. Only able to see active service in the dog-days of the conflict, he was unlucky enough to be close to a fuel dump which was hit by a stray shell. There’s a line from a song about that war, which goes,

“Never knew there was worse things than dying..”

Those words might be an extreme take on the scars of war, but Urban Raven’s face is a shiny and distorted mass of scar tissue, and he has become adept at ignoring the fascinated horror on people’s faces when they see him for the first time. His disfigurement might do him no favours with ordinary people, but has learned that it gives him an extra edge when dealing with criminals.

Against a fascinating background of the attempts by British fascists to emulate their German and Italian counterparts, and the ongoing saga of a member of the royal family who wants to marry an American divorcee (plus ça change?) Raven’s problems become deeper and wider as he falls foul of the secretive Special Branch, begins to suspect his wife’s fidelity and then – as if his problems weren’t serious enough – finds himself mired in a a political and criminal conspiracy.

As in every other Chris Nickson novel I have read, the city of Leeds is the central character. Whether it’s Richard Nottingham, Tom Harper, Lottie Armstrong or, now, Urban Raven treading its grand thoroughfares and mean ginnels, Leeds remains gritty, grimy, home to all manner of beauty and bestiality, but always vibrant. There is a wonderful feeling of continuity running through the books; it’s as if each police officer is carrying the baton handed on by a predecessor; Nottingham to Harper, Harper to Raven, Raven to Armstrong. The characters inhabit the same city, though; The Headrow is ever present, as are Briggate and Kirkgate, their suffixes names testifying to their antiquity.

The Dead On Leave is very bleak in places. Hope is in short supply among the working people in Leeds, and men have no qualms about building a wooden platform for Moseley to rant from, because a job is a job; consciences are a luxury way beyond the reach of folk whose families have empty bellies. Nickson (right) is a writer, with social justice at the front of his mind and he wears his heart on his sleeve. I doubt that he and I agree on much in today’s political world, but I can think of no modern British author who writes with such passion and fluency about historical social issues.

The Dead On Leave is very bleak in places. Hope is in short supply among the working people in Leeds, and men have no qualms about building a wooden platform for Moseley to rant from, because a job is a job; consciences are a luxury way beyond the reach of folk whose families have empty bellies. Nickson (right) is a writer, with social justice at the front of his mind and he wears his heart on his sleeve. I doubt that he and I agree on much in today’s political world, but I can think of no modern British author who writes with such passion and fluency about historical social issues.

Make no mistake, though. The Dead On Leave is not a sermon, and it does not wag a finger in admonition. It is an excellent crime novel, a perfect example of a police-procedural and it ushers on stage another compelling character in Nickson’s Leeds Dramatis Personnae. The book is published by Endeavour Quill and is available now in Kindle and as a paperback.

Hal Westaway is no crook. She is not an opportunist. She has a conscience. She instinctively understands the difference between meum and teum. And yet. And yet. The gangster from whom she unwisely took out a desperation loan is angry and anxious for his 300%. Hal’s Brighton flat has already been turned over, and she knows that broken bones are next on the agenda. So, she accepts the invitation from the late Mrs Westaway’s solicitor to travel down to Cornwall to meet the family she never knew she had.

Hal Westaway is no crook. She is not an opportunist. She has a conscience. She instinctively understands the difference between meum and teum. And yet. And yet. The gangster from whom she unwisely took out a desperation loan is angry and anxious for his 300%. Hal’s Brighton flat has already been turned over, and she knows that broken bones are next on the agenda. So, she accepts the invitation from the late Mrs Westaway’s solicitor to travel down to Cornwall to meet the family she never knew she had. Ruth Ware (right) is not the first writer – nor will she be the last – to explore the lurid charms of a decaying mansion, its ghosts both real and imagined, and the dusty terrors of death, but she makes a bloody good job of it in The Death of Mrs Westaway. Hal Westaway is a delightful character, and you would require a heart of the hardest granite not to sympathise with her and the exquisite dilemma she faces. The plot is a dazzling mix of twists, surprises, and just the right amount of improbability. The Death of Mrs Westaway is a thriller which makes you keep the bedroom light on, and long for the safety of daylight. It looks like being another bestseller for Ruth Ware, and you can judge for yourselves on June 28th, when the book will be published by

Ruth Ware (right) is not the first writer – nor will she be the last – to explore the lurid charms of a decaying mansion, its ghosts both real and imagined, and the dusty terrors of death, but she makes a bloody good job of it in The Death of Mrs Westaway. Hal Westaway is a delightful character, and you would require a heart of the hardest granite not to sympathise with her and the exquisite dilemma she faces. The plot is a dazzling mix of twists, surprises, and just the right amount of improbability. The Death of Mrs Westaway is a thriller which makes you keep the bedroom light on, and long for the safety of daylight. It looks like being another bestseller for Ruth Ware, and you can judge for yourselves on June 28th, when the book will be published by

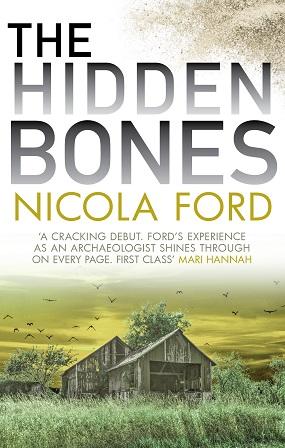

Clare Hills is an archaeologist who is struggling to hold her life together after the death of her husband. Her grief at his passing is tempered by the fact that he has left her virtually penniless. When she is invited by her former tutor, Dr David Barbrook, to help explore and archive the papers of Gerald Hart, she welcomes the chance to use her expertise. Hart was a gentleman archaeologist whose Palladian villa, Hungerbourne Manor, was the centre of his life’s work – investigating the Hungerbourne Barrows. The Bronze Age burial sites were Hart’s obsession, but whatever secrets they held, he seems to have taken them with him to his grave.

Clare Hills is an archaeologist who is struggling to hold her life together after the death of her husband. Her grief at his passing is tempered by the fact that he has left her virtually penniless. When she is invited by her former tutor, Dr David Barbrook, to help explore and archive the papers of Gerald Hart, she welcomes the chance to use her expertise. Hart was a gentleman archaeologist whose Palladian villa, Hungerbourne Manor, was the centre of his life’s work – investigating the Hungerbourne Barrows. The Bronze Age burial sites were Hart’s obsession, but whatever secrets they held, he seems to have taken them with him to his grave. I have many guilty pleasures, and one of them is being a sucker for a crime novel where the landscape plays a vital part in the plot. My two particular favourite writers in this regard are Phil Rickman and Jim Kelly, but with this excellent debut novel, Nicola Ford (right) has elbowed herself into their company.

I have many guilty pleasures, and one of them is being a sucker for a crime novel where the landscape plays a vital part in the plot. My two particular favourite writers in this regard are Phil Rickman and Jim Kelly, but with this excellent debut novel, Nicola Ford (right) has elbowed herself into their company.

Detectives come in all nationalities these days. Anya Lipska in her Kiszka and Kershaw series has explored the Polish angle, while one of the most formidable female operators in fiction, Victoria Iphigenia Warshawski is, of course Polish on her father’s side. Now, Hania Allen (left) introduces us to DS Dania Gorska, described as “a stranger in a foreign land.” Crime however is multi-lingual and knows no national boundaries, and Gorska is assigned to the Police Scotland Specialist Crime Division in Dundee, on the banks of the River Tay. The Polish-born police officer becomes involved in the investigation of a bizarre series of killings which seem connected to a druidic cult.The Polish Detective is

Detectives come in all nationalities these days. Anya Lipska in her Kiszka and Kershaw series has explored the Polish angle, while one of the most formidable female operators in fiction, Victoria Iphigenia Warshawski is, of course Polish on her father’s side. Now, Hania Allen (left) introduces us to DS Dania Gorska, described as “a stranger in a foreign land.” Crime however is multi-lingual and knows no national boundaries, and Gorska is assigned to the Police Scotland Specialist Crime Division in Dundee, on the banks of the River Tay. The Polish-born police officer becomes involved in the investigation of a bizarre series of killings which seem connected to a druidic cult.The Polish Detective is  This international military thriller also has a Polish connection. A despotic Russian president has built a devastating new weapon, and its first strike is against Warsaw, via malware which destroys the country’s banking system. As the rest of Europe’s financial world goes into a fatal tailspin, the President of The United States has to meet fire with fire, and she calls in flying ace Brad McLanahan and his deadly Scion team to thwart the ambitions of the megalomaniac Gennady Gryzslov. Price of Duty, by Dale Brown (right) was previously published in hardback and Kindle, but will be available as a Corsair paperback

This international military thriller also has a Polish connection. A despotic Russian president has built a devastating new weapon, and its first strike is against Warsaw, via malware which destroys the country’s banking system. As the rest of Europe’s financial world goes into a fatal tailspin, the President of The United States has to meet fire with fire, and she calls in flying ace Brad McLanahan and his deadly Scion team to thwart the ambitions of the megalomaniac Gennady Gryzslov. Price of Duty, by Dale Brown (right) was previously published in hardback and Kindle, but will be available as a Corsair paperback  When Josephine ‘Joey’ Mullen – plus her new husband – return from four years working abroad with nowhere to stay, they are grateful for the opportunity to crash in Joey’s brother’s house in Bristol, just until they get themselves settled. Joey’s older brother Jack is a respected consultant heart surgeon, with a staid and rather disapproving wife. As Joey looks for work, she becomes interested – too interested – in Jack’s next-door neighbour. Tom Fitzwilliam is a successful Head Teacher, brought in to re-invigorate a failing school. He is twice Joey’s age, but in spite of husband Alfie’s charm and good looks, she becomes obsessed with the fifty-five year old. What follows is a gripping and tense study in recklessness, obsession- and murder. This psychological thriller from Lisa Jewell (above left) will be published

When Josephine ‘Joey’ Mullen – plus her new husband – return from four years working abroad with nowhere to stay, they are grateful for the opportunity to crash in Joey’s brother’s house in Bristol, just until they get themselves settled. Joey’s older brother Jack is a respected consultant heart surgeon, with a staid and rather disapproving wife. As Joey looks for work, she becomes interested – too interested – in Jack’s next-door neighbour. Tom Fitzwilliam is a successful Head Teacher, brought in to re-invigorate a failing school. He is twice Joey’s age, but in spite of husband Alfie’s charm and good looks, she becomes obsessed with the fifty-five year old. What follows is a gripping and tense study in recklessness, obsession- and murder. This psychological thriller from Lisa Jewell (above left) will be published

I was working in Australia when Peter Weir’s 1975 film Picnic At Hanging Rock premiered. I remember pub and dinner party talk for months after being dominated by interpretations and explanations about what might have happened to the ‘lost girls’. In the endpapers of Last Time I Lied American author Riley Sager, (left) acknowledges his debt to this film (and the short story on which it was based). Instead of a 1900 Melbourne, Sager beams us into up-country New York State in, more or less, our times.

I was working in Australia when Peter Weir’s 1975 film Picnic At Hanging Rock premiered. I remember pub and dinner party talk for months after being dominated by interpretations and explanations about what might have happened to the ‘lost girls’. In the endpapers of Last Time I Lied American author Riley Sager, (left) acknowledges his debt to this film (and the short story on which it was based). Instead of a 1900 Melbourne, Sager beams us into up-country New York State in, more or less, our times. Emma’s summer idyll is destined to come to an abrupt and tragic end, however, when the three older girls in the cabin disappear one night, never to return. Despite the massive search and rescue operation, Vivian, Natalie and Allison remain missing, and Franny is forced to close the camp in disarray.

Emma’s summer idyll is destined to come to an abrupt and tragic end, however, when the three older girls in the cabin disappear one night, never to return. Despite the massive search and rescue operation, Vivian, Natalie and Allison remain missing, and Franny is forced to close the camp in disarray.

Mr Bulmer is a uniquely repulsive little man who manages a dry cleaning shop in Mayfair, and uses the opportunity of searching through the jackets and trouser pockets of wealthy individuals to service his own very profitable blackmail industry. His malignant little sideline has provided him with a regular income – and driven at least one of his victims to suicide. When he seizes upon what he sees as the opportunity of a lifetime, he is unaware that is about to be snared by his own hook. John Bingham, in addition to being a writer of distinction, was also a highly placed official in British Intelligence operations.

Mr Bulmer is a uniquely repulsive little man who manages a dry cleaning shop in Mayfair, and uses the opportunity of searching through the jackets and trouser pockets of wealthy individuals to service his own very profitable blackmail industry. His malignant little sideline has provided him with a regular income – and driven at least one of his victims to suicide. When he seizes upon what he sees as the opportunity of a lifetime, he is unaware that is about to be snared by his own hook. John Bingham, in addition to being a writer of distinction, was also a highly placed official in British Intelligence operations. Crispin, aka Robert Bruce Montgomery, is best known for his Gervase Fen novels but here he spins a delightfully black tale of a struggling writer whose hospitality is impinged upon by a pair of runaways, both seeking a new life away from their spouses. Crispin intersperses the narrative with vivid accounts of a writer desperately searching for the words which will bring his latest novel to life. Sadly for the would-be lovers, their fate is to be organic fertiliser for Mr Bradley’s vegetable plot.

Crispin, aka Robert Bruce Montgomery, is best known for his Gervase Fen novels but here he spins a delightfully black tale of a struggling writer whose hospitality is impinged upon by a pair of runaways, both seeking a new life away from their spouses. Crispin intersperses the narrative with vivid accounts of a writer desperately searching for the words which will bring his latest novel to life. Sadly for the would-be lovers, their fate is to be organic fertiliser for Mr Bradley’s vegetable plot. Davidson’s internationally themed thrillers were his bread and butter, but we must not forget that he was a writer of immense sensitivity with a wide range of influences. His own upbringing as a child of a hard-scrabble Polish-Jewish family might have made it unlikely that he would compose a chilling tale of murder on the banks of s Scottish river frequented only by rich Englishmen with the money to buy the rights to snare incoming salmon. A man whose sexual abilities have been devastated by a potentially fatal illness plans revenge on a friend whose libido remains undiminished. The denouement takes place on the banks of Scotland’s sacred salmon river – the Spey.

Davidson’s internationally themed thrillers were his bread and butter, but we must not forget that he was a writer of immense sensitivity with a wide range of influences. His own upbringing as a child of a hard-scrabble Polish-Jewish family might have made it unlikely that he would compose a chilling tale of murder on the banks of s Scottish river frequented only by rich Englishmen with the money to buy the rights to snare incoming salmon. A man whose sexual abilities have been devastated by a potentially fatal illness plans revenge on a friend whose libido remains undiminished. The denouement takes place on the banks of Scotland’s sacred salmon river – the Spey. Colin Dexter? Cue Oxford, an irascible senior policeman, pints of English beer and crossword puzzles? Think on. When this story was published, Dexter was already four books into his Inspector Morse series, but the TV adaptations were still six years away. In this tale, Dexter takes us to, of all places, rural America, where a coach load of middle-aged and elderly tourists take a rest stop at the eponymous wayside hotel. The action is centred around a game of vingt-et-un, designed to empty the wallets of the gullible travellers. Dexter describes a scam-within-a -scam -but saves until the last few paragraphs a chilling finale in which the scammer becomes the scammed.

Colin Dexter? Cue Oxford, an irascible senior policeman, pints of English beer and crossword puzzles? Think on. When this story was published, Dexter was already four books into his Inspector Morse series, but the TV adaptations were still six years away. In this tale, Dexter takes us to, of all places, rural America, where a coach load of middle-aged and elderly tourists take a rest stop at the eponymous wayside hotel. The action is centred around a game of vingt-et-un, designed to empty the wallets of the gullible travellers. Dexter describes a scam-within-a -scam -but saves until the last few paragraphs a chilling finale in which the scammer becomes the scammed. People might forget that Antonia Fraser, as well as being the daughter of Lord Longford the widow of Harold Pinter and a superb historical biographer, is no slouch when it comes to crime fiction. Here, she taps into that strange love affair that English people have with their dogs. Richard Gavin is a successful barrister (is there ever another sort?) who has kept his upper lip stiff and tremble-free during the death of his first wife, and remarried. The new lady of the Gavin household is Paulina – young. bright and adorable. Her judgment, however is brought into question, when her decision to put an aged, smelly and incontinent spaniel out of its misery coincides with Richard opening an ominous letter from his London doctor.

People might forget that Antonia Fraser, as well as being the daughter of Lord Longford the widow of Harold Pinter and a superb historical biographer, is no slouch when it comes to crime fiction. Here, she taps into that strange love affair that English people have with their dogs. Richard Gavin is a successful barrister (is there ever another sort?) who has kept his upper lip stiff and tremble-free during the death of his first wife, and remarried. The new lady of the Gavin household is Paulina – young. bright and adorable. Her judgment, however is brought into question, when her decision to put an aged, smelly and incontinent spaniel out of its misery coincides with Richard opening an ominous letter from his London doctor. This is the most shocking and slap-in-the-face story in the collection. I would go as far as to suggest that it would not have been written – let alone published – today, with our heightened awareness of child abuse and domestic violence. As an account of casual violence, domestic cruelty, alcohol abuse – and the pervasive power of the Roman Catholic church – it makes for uncomfortable reading. Highsmith’s misanthropy can never have been more glaringly or honestly displayed. her publisher wrote:

This is the most shocking and slap-in-the-face story in the collection. I would go as far as to suggest that it would not have been written – let alone published – today, with our heightened awareness of child abuse and domestic violence. As an account of casual violence, domestic cruelty, alcohol abuse – and the pervasive power of the Roman Catholic church – it makes for uncomfortable reading. Highsmith’s misanthropy can never have been more glaringly or honestly displayed. her publisher wrote: Like Hubbard’s longer works, which are examined in this feature, a dream-like quality pervades this story, but the dreams are not necessarily pleasant ones. The first words are:

Like Hubbard’s longer works, which are examined in this feature, a dream-like quality pervades this story, but the dreams are not necessarily pleasant ones. The first words are: This exquisite masterpiece tells of a nameless girl, an orphan, who is brought up in a loveless terraced house in east London, the home of her Uncle Victor and Aunt Gladys. Her only joy is the adjacent cemetery which becomes a place of mystical and endless attraction:

This exquisite masterpiece tells of a nameless girl, an orphan, who is brought up in a loveless terraced house in east London, the home of her Uncle Victor and Aunt Gladys. Her only joy is the adjacent cemetery which becomes a place of mystical and endless attraction:

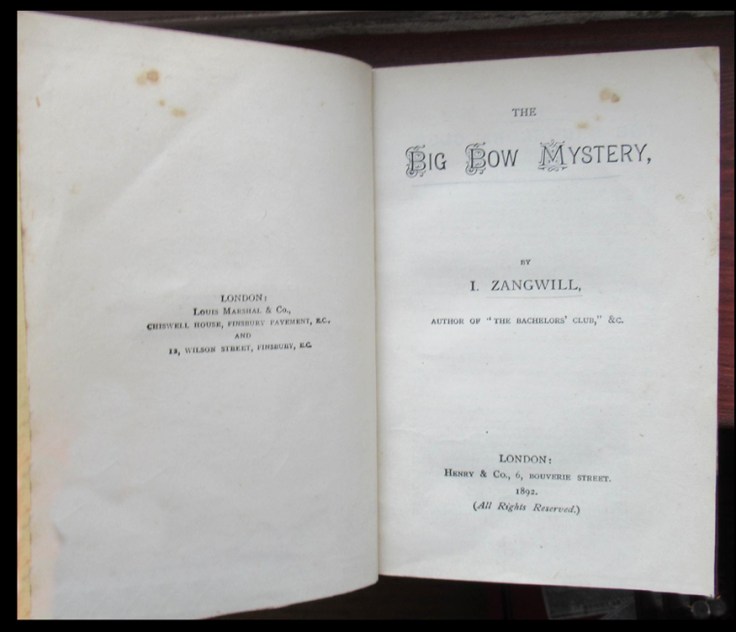

The ‘Bow’ in the title is not some fabric adornment, but the working class district in East London. If you were born within earshot of its church bells, then you were said to be a true Cockney. It’s December, and the nineteenth century is on its last legs. A dense morning fog, aided and abetted by the smoke of a million coal fires, swirls around the mean streets.

The ‘Bow’ in the title is not some fabric adornment, but the working class district in East London. If you were born within earshot of its church bells, then you were said to be a true Cockney. It’s December, and the nineteenth century is on its last legs. A dense morning fog, aided and abetted by the smoke of a million coal fires, swirls around the mean streets. The formidable lady has overslept, but after lighting the downstairs fire, she remembers to wake one of the lodgers. Arthur Constant is an idealist, and a campaigner for workers’ rights. She bangs on his bedroom door, then makes the day’s first pot of tea. Taking a tray upstairs, she calls again. Still no response. She peeps through the keyhole, but the key is firmly in place. As she pounds on the door once again, she has a premonition that something is very, very wrong. So she summons her neighbour, the redoubtable retired detective Mr George Grodman. He batters down the door, which was locked and bolted from the inside, and is forced to cover Mrs Drabdump’s eyes from the horrors within…

The formidable lady has overslept, but after lighting the downstairs fire, she remembers to wake one of the lodgers. Arthur Constant is an idealist, and a campaigner for workers’ rights. She bangs on his bedroom door, then makes the day’s first pot of tea. Taking a tray upstairs, she calls again. Still no response. She peeps through the keyhole, but the key is firmly in place. As she pounds on the door once again, she has a premonition that something is very, very wrong. So she summons her neighbour, the redoubtable retired detective Mr George Grodman. He batters down the door, which was locked and bolted from the inside, and is forced to cover Mrs Drabdump’s eyes from the horrors within… Some contemporary critics were puzzled and irritated by Zangwill’s satirical style. They felt that there was no place for comedy in the tale of a young man, dead in his bed, his throat cut from ear to ear. The exchanges in the court scenes between pompous officials and outspoken ‘low life’ types on the jury are delightfully reminiscent of similar encounters between Mr Pooter and disrespectful tradesmen in that classic of English humour, The Diary of A Nobody.

Some contemporary critics were puzzled and irritated by Zangwill’s satirical style. They felt that there was no place for comedy in the tale of a young man, dead in his bed, his throat cut from ear to ear. The exchanges in the court scenes between pompous officials and outspoken ‘low life’ types on the jury are delightfully reminiscent of similar encounters between Mr Pooter and disrespectful tradesmen in that classic of English humour, The Diary of A Nobody.