Philip Kerr’s Bernie Gunther novels bestride the 20th century, from the rise of the Nazis in 1930s Germany to the post war period when many countries still sheltered mysterious German gentlemen whose collective past has been, of necessity, reinvented. Gunther is a smart talking, smart thinking policeman who has kept his sanity intact – but his conscience rather less so – by dealing with such elemental forces as Reinhardt Heydrich, Joseph Goebbels, Juan and Evita Peron, and Adolf Eichmann.

Philip Kerr’s Bernie Gunther novels bestride the 20th century, from the rise of the Nazis in 1930s Germany to the post war period when many countries still sheltered mysterious German gentlemen whose collective past has been, of necessity, reinvented. Gunther is a smart talking, smart thinking policeman who has kept his sanity intact – but his conscience rather less so – by dealing with such elemental forces as Reinhardt Heydrich, Joseph Goebbels, Juan and Evita Peron, and Adolf Eichmann.

A Man Without Breath (2013) sees Gunther is working for an organisation whose very existence may seem improbable, given the historical context, but Die Wehrmacht Untersuchungsstelle (Wehrmacht Bureau of War Crimes) was set up in 1939 and continued its work until 1945. In 1943, on a mission from the Minister for Propaganda, Joseph Goebbels, Gunther is sent to Smolensk and entrusted with proving that the thousands of corpses lying frozen beneath the trees of the nearby Katyn Forest are those of Polish army officers and intellectuals murdered by the Russian NKVD, and not those of Jews murdered by the SS.

A Man Without Breath (2013) sees Gunther is working for an organisation whose very existence may seem improbable, given the historical context, but Die Wehrmacht Untersuchungsstelle (Wehrmacht Bureau of War Crimes) was set up in 1939 and continued its work until 1945. In 1943, on a mission from the Minister for Propaganda, Joseph Goebbels, Gunther is sent to Smolensk and entrusted with proving that the thousands of corpses lying frozen beneath the trees of the nearby Katyn Forest are those of Polish army officers and intellectuals murdered by the Russian NKVD, and not those of Jews murdered by the SS.

The action is set against a resurgent Red Army slowly grinding its way west, and a small but growing body of opinion among the more aristocratic members of  the German military that Hitler is a dangerous upstart who has already damaged the country beyond repair, and must be stopped. Adrift on a sea of violent corruption, Gunther constantly plays the role of the decent man, but in the end, he follows one theology, and one theology only. If he wakes up the next day with his head firmly attached to his shoulders, and has feeling in his extremities, then he has done the right thing. His conscience has not died, but it is far from well; it competes a whole chorale of competing voices in his head, each wishing to be heard. As he is left helpless by the world of spin and disinformation orchestrated by Dr Goebbels, (right) he must resort to his basic copper’s instincts to protect himself and uncover the truth.

the German military that Hitler is a dangerous upstart who has already damaged the country beyond repair, and must be stopped. Adrift on a sea of violent corruption, Gunther constantly plays the role of the decent man, but in the end, he follows one theology, and one theology only. If he wakes up the next day with his head firmly attached to his shoulders, and has feeling in his extremities, then he has done the right thing. His conscience has not died, but it is far from well; it competes a whole chorale of competing voices in his head, each wishing to be heard. As he is left helpless by the world of spin and disinformation orchestrated by Dr Goebbels, (right) he must resort to his basic copper’s instincts to protect himself and uncover the truth.

The Katyn Forest murders are a matter of historical record, but it is only in relatively recent times that Russia has officially admitted responsibility for the massacres. As recently as 6 December 2010, Russian President Dmitry Medvedev expressed commitment to uncovering the whole truth about the massacre, stating “Russia has recently taken a number of unprecedented steps towards clearing up the legacy of the past. We will continue in this direction”.

History tells us that the dead of Katyn included an admiral, two generals, 24 colonels, 79 lieutenant colonels, 258 majors, 654 captains, 17 naval captains, 85 privates, 3,420 non-commissioned officers, and seven chaplains, 200 pilots, government representatives and royalty (a prince and 43 officials), and civilians (three landowners, 131 refugees, 20 university professors, 300 physicians, several hundred lawyers, engineers, and teachers, and more than 100 writers and journalists.

We know the terrible details but Gunther only has his suspicions. Kerr weaves a brilliant tale where Gunther’s arrival at the truth has the ironic consequence of removing culpability for the deaths from one group of brutal criminals and bestowing it upon another. Those of us who are old enough to remember the post-war years, if only as children, will be familiar with the feeling that the Russians were bastards every bit as awful as their Nazi opponents, but at least they were our bastards – at least until they reached Berlin.

A Man Without Breath is available in all formats.

We are in the weeks leading up to Christmas 1944, deep in what would prove to be the last winter of a war which, thanks to the Luftwaffe, had brought death and destruction to the doorsteps of ordinary people in towns and cities up and down the country. German aircraft no longer drone over the streets of London; instead, the Dorniers and Heinkels have been replaced by an even more demoralising menace – the seemingly random strikes by V1 and V2 rockets. Despite the fact that the rockets need no visible target to aim at, the ubiquitous blackout is still in force. An Air Raid Precaution Warden, whose job has become as redundant as that of those manning anti-aircraft batteries, makes a chilling discovery. He stumbles – literally – on the body of a young woman. Her neck has been broken by someone clearly well-versed in killing, and the only clue is a number of spent matches lying by the body.

We are in the weeks leading up to Christmas 1944, deep in what would prove to be the last winter of a war which, thanks to the Luftwaffe, had brought death and destruction to the doorsteps of ordinary people in towns and cities up and down the country. German aircraft no longer drone over the streets of London; instead, the Dorniers and Heinkels have been replaced by an even more demoralising menace – the seemingly random strikes by V1 and V2 rockets. Despite the fact that the rockets need no visible target to aim at, the ubiquitous blackout is still in force. An Air Raid Precaution Warden, whose job has become as redundant as that of those manning anti-aircraft batteries, makes a chilling discovery. He stumbles – literally – on the body of a young woman. Her neck has been broken by someone clearly well-versed in killing, and the only clue is a number of spent matches lying by the body. There is more than a touch of The Golden Age about this novel, but it is much more than a pastiche. Although the killing of Rosa Nowak is eventually solved, with a regulation dramatic climax in a snow-bound country house, Rennie Airth allows us to breathe, smell and taste the air of an England almost – but not quite – beaten down by the privations of war. Many of the characters have menfolk away at the war, including Madden himself and his wife Helen. Their son is in the Royal Navy, on the rough winter seas escorting convoys. The contrast between life in the city and in the country is etched deep. In the city, restaurant meals are frequently inedible, the black market thrives unchecked due to depleted police manpower, and even the newsprint bearing cheering propaganda from the government is subject to rationing. Travelling anywhere, unless you are fiddling your petrol coupons, is arduous and unpleasant.

There is more than a touch of The Golden Age about this novel, but it is much more than a pastiche. Although the killing of Rosa Nowak is eventually solved, with a regulation dramatic climax in a snow-bound country house, Rennie Airth allows us to breathe, smell and taste the air of an England almost – but not quite – beaten down by the privations of war. Many of the characters have menfolk away at the war, including Madden himself and his wife Helen. Their son is in the Royal Navy, on the rough winter seas escorting convoys. The contrast between life in the city and in the country is etched deep. In the city, restaurant meals are frequently inedible, the black market thrives unchecked due to depleted police manpower, and even the newsprint bearing cheering propaganda from the government is subject to rationing. Travelling anywhere, unless you are fiddling your petrol coupons, is arduous and unpleasant.

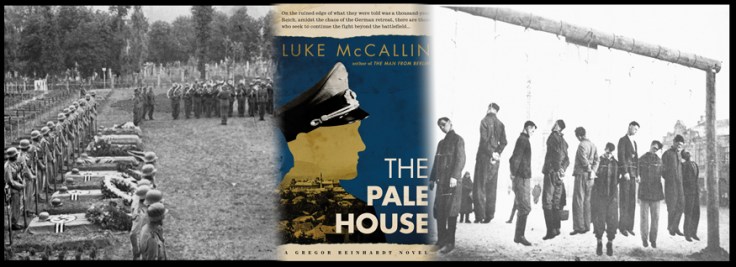

finds employment as an officer in the Feldjaegerkorps. His creator, Luke McCallin, (right) introduced us to Hauptmann Reinhardt in

finds employment as an officer in the Feldjaegerkorps. His creator, Luke McCallin, (right) introduced us to Hauptmann Reinhardt in  A LILY OF THE FIELD by John Lawton

A LILY OF THE FIELD by John Lawton