December 1939. Berlin. The snow lies deep and crisp and even, and Kriminalpolizei Inspector Horst Shenke is summoned to the Reich Security Main Office to meet Oberführer Heinrich Müller, a protege of Reinhardt Heydrich and recently appointed head of the Gestapo. Müller has a tricky problem in the shape of a former film star, Gerda Korzeny. Her husband is a lawyer and Nazi Party member who specialises in redrafting potentially awkward pieces of existing legislation in favour of the Party. And now Gerda is dead. Found by a railway track with awful head wounds. She had also been brutally raped. But what does this have to do with Heinrich Müller? His problem is that Gerda Korzeny was known to be having an affair with Oberst Karl Dorner, an officer in the Abwehr, Germany’s military intelligence organisation, and the Gestapo man wants the matter dealt with quickly and discreetly.

December 1939. Berlin. The snow lies deep and crisp and even, and Kriminalpolizei Inspector Horst Shenke is summoned to the Reich Security Main Office to meet Oberführer Heinrich Müller, a protege of Reinhardt Heydrich and recently appointed head of the Gestapo. Müller has a tricky problem in the shape of a former film star, Gerda Korzeny. Her husband is a lawyer and Nazi Party member who specialises in redrafting potentially awkward pieces of existing legislation in favour of the Party. And now Gerda is dead. Found by a railway track with awful head wounds. She had also been brutally raped. But what does this have to do with Heinrich Müller? His problem is that Gerda Korzeny was known to be having an affair with Oberst Karl Dorner, an officer in the Abwehr, Germany’s military intelligence organisation, and the Gestapo man wants the matter dealt with quickly and discreetly.

We learn that Schenke is a very good copper, but that his career has stalled because he has, thus far, refused to become a Party member. In his younger days, Schenke was a well-known racing driver, until a near-fatal accident forced him to quit the sport. His only legacy from those heady days is a permanently damaged knee. He is romantically involved with a woman called Karin Canaris, and if that surname rings a bell with WW2 history buffs, yes, she is the niece of the real-life head of the Abwehr, Admiral William Canaris.

Although he initially believes that the case will not bring him into direct conflict with local Nazi officials, Schenke’s discovery that Berlin has a serial killer on the loose is of little comfort, as everyone in the Party, from Goebbels down to the lowliest apartment block supervisor is anxious to preserve public confidence in these early months of the war. Oberst Dorner takes a step or two down the ladder of Schenke’s suspects when the killer strikes again, but this time fails to finish the job. The victim survives with bruises and shock, but Schenke finds himself in a tight corner when, after investigating the young woman’s several false identities, he discovers that her real name is Ruth Frankel, and she is Jewish. In normal times, her racial profile shouldn’t matter, but these are not normal times, and Party officials take a dim view of wasting valuable resources on any case involving Jews.

Oberführer Müller, (right) in an attempt to keep tracks on what Schenke is doing, sends a young Gestapo officer called Liebvitz to shadow the Kripo officer, and that allows us to meet a rather unusual fellow. These days, we would probably say he has Asperger’s Syndrome, as he takes everything literally, has no sense of humour and a formidable eye for detail. He is also a crack shot, and this skill serves both Schenke and the department well by the end of the book.

Oberführer Müller, (right) in an attempt to keep tracks on what Schenke is doing, sends a young Gestapo officer called Liebvitz to shadow the Kripo officer, and that allows us to meet a rather unusual fellow. These days, we would probably say he has Asperger’s Syndrome, as he takes everything literally, has no sense of humour and a formidable eye for detail. He is also a crack shot, and this skill serves both Schenke and the department well by the end of the book.

Simon Scarrow cleverly allows Schenke makes one or two mistakes, which makes for a very tense finale, but also establishes him as a human being like so many other fictional coppers before him – tired to the point of exhaustion, frustrated by officialdom and trouble by his conscience. Before the book ends, we also meet the deeply sinister – despite a superficial icy charm – Reinhardt Heydrich.

Comparisons between the worlds of Horst Schenke, Philip Kerr’s Bernie Gunther and David Downing’s John Russell are inevitable, but not in any way damaging. A good as they are, neither Kerr nor Downing have taken out a copyright on the world of WW2 Berlin. Simon Scarrow shines a new light on a city and a time that many of us think we know well. He creates vivid new characters – and revitalises our enduring fascination with some of the historical monsters that stalked the earth in the 1930s and 40s. I sincerely hope that this becomes a series. If so, it will run for a long time, and grip many thousands of readers. Blackout was first published in hardback in March this year, and this Headline paperback is available now.

Years later

Years later

We are, as ever, in London, but it is 1940. The Phony War is over, and the Luftwaffe are targetting industrial sites they believe to be involved in making parts for military aircraft. When several important employees of one such factory are burgled – clearly by an expert – but with nothing other than trinkets stolen, Hardcastle believes he may be on the track of a German spy on the look-out for plans, blueprints or important military information. Hardcastle has to deal with The Special Branch, but finds them about as co-operative as they were with his father a couple of decades earlier. This has a certain tinge of irony, as part of the author’s distinguished police career was spent as a Special Branch Operative.

We are, as ever, in London, but it is 1940. The Phony War is over, and the Luftwaffe are targetting industrial sites they believe to be involved in making parts for military aircraft. When several important employees of one such factory are burgled – clearly by an expert – but with nothing other than trinkets stolen, Hardcastle believes he may be on the track of a German spy on the look-out for plans, blueprints or important military information. Hardcastle has to deal with The Special Branch, but finds them about as co-operative as they were with his father a couple of decades earlier. This has a certain tinge of irony, as part of the author’s distinguished police career was spent as a Special Branch Operative.

Any novel which features – in no particular order – Commander Ian Fleming, King Zog of Albania, a dodgy lawyer called Pentangle Underhill, and a Detective Chief Inspector named The Hon. Edgar Walter Septimus Saxe-Coburg promises to be a great deal of fun, and Murder At The Ritz by Jim Eldridge didn’t disappoint. It is set in London in August 1940, and Ahmet Muhtar Zogolli, better known as King Zog of Albania (left) has been smuggled out of his homeland after its invasion by Mussolini’s Italy, and he has now taken over the entire third floor of London’s Ritz Hotel, complete with various retainers and bodyguards – as well as a tidy sum in gold bullion.

Any novel which features – in no particular order – Commander Ian Fleming, King Zog of Albania, a dodgy lawyer called Pentangle Underhill, and a Detective Chief Inspector named The Hon. Edgar Walter Septimus Saxe-Coburg promises to be a great deal of fun, and Murder At The Ritz by Jim Eldridge didn’t disappoint. It is set in London in August 1940, and Ahmet Muhtar Zogolli, better known as King Zog of Albania (left) has been smuggled out of his homeland after its invasion by Mussolini’s Italy, and he has now taken over the entire third floor of London’s Ritz Hotel, complete with various retainers and bodyguards – as well as a tidy sum in gold bullion.  Back to the story, and when a corpse is discovered in one of the King’s suites, Coburg is called in to investigate. The attempt to relieve the Albanian monarch of his treasure sparks off a turf war between two London gangs who, rather like the Krays and the Richardsons in the 1960s, occupy territories ‘norf’ and ‘sarf’ of the river. After several more dead bodies and an entertaining sub-plot featuring Coburg’s romance with Rosa Weeks, a beautiful and talented young singer, there is a dramatic finale involving a shoot-out near the Russian Embassy. This is a highly enjoyable book that occupies the same territory as John Lawton’s

Back to the story, and when a corpse is discovered in one of the King’s suites, Coburg is called in to investigate. The attempt to relieve the Albanian monarch of his treasure sparks off a turf war between two London gangs who, rather like the Krays and the Richardsons in the 1960s, occupy territories ‘norf’ and ‘sarf’ of the river. After several more dead bodies and an entertaining sub-plot featuring Coburg’s romance with Rosa Weeks, a beautiful and talented young singer, there is a dramatic finale involving a shoot-out near the Russian Embassy. This is a highly enjoyable book that occupies the same territory as John Lawton’s

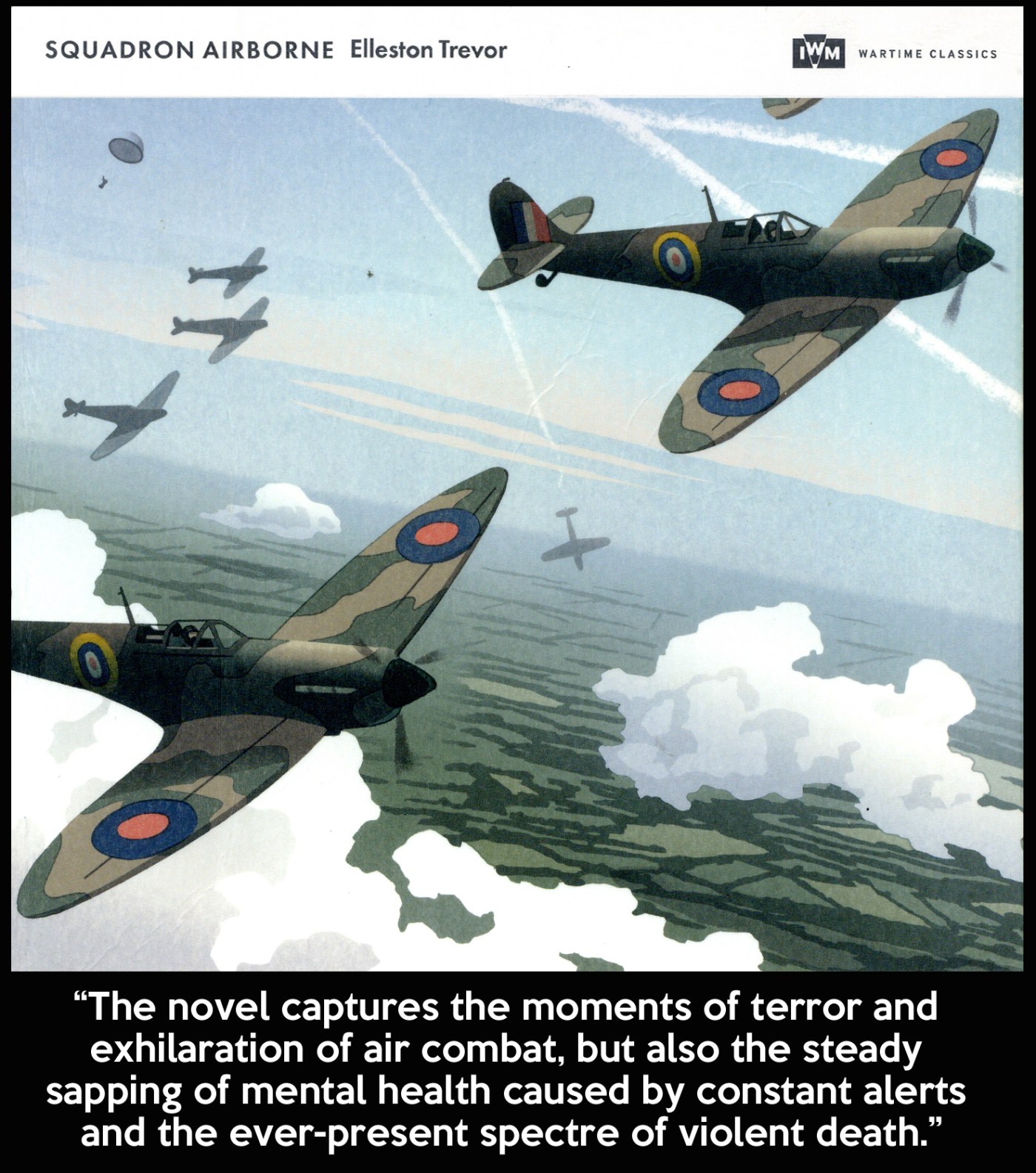

TO ALL THE LIVING . . . Between the covers

This is the latest in the series of excellent reprints from the Imperial War Museum. They have ‘rediscovered’ novels written about WW2, mostly by people who experienced the conflict either home or away. Previous books can be referenced by clicking this link.

We are, then, immediately into the dangerous territory of judging creative artists because of their politics, which never ends well, whether it involves the Nazis ‘cancelling’ Mahler because he was Jewish or more recent critics shying away from Wagner because he was anti-semitic and, allegedly, admired by senior figures in the Third Reich. The longer debate is for another time and another place, but it is an inescapable fact that many great creative people, if not downright bastards, were deeply unpleasant and misguided. To name but a few, I don’t think I would have wanted to list Caravaggio, Paul Gauguin, Evelyn Waugh, Eric Gill or Patricia Highsmith among my best friends, but I would be mortified not to be able to experience the art they made.

So, could Monica Felton write a good story, away from hymning the praises of KIm Il Sung and his murderous regime? To All The Living (1945) is a lengthy account of life in a British munitions factory during WW2, and is principally centred around Griselda Green, a well educated young woman who has decided to do her bit for the country. To quickly answer my own question, the answer is a simple, “Yes, she could.”

Another question could be, “Does she preach?“ That, to my mind, is the unforgivable sin of any novelist with strong political convictions. Writers such as Dickens and Hardy had an agenda, certainly, but they subtly inserted this between the lines of great story-telling. Felton is no Dickens or Hardy, but she casts a wry glance at the preposterous bureaucracy that ran through the British war effort like the veins in blue cheese. She highlights the endless paperwork, the countless minions who supervised the completion of the bumf, and the men and women – usually elevated from being section heads in the equivalent of a provincial department store – who ruled over the whole thing in a ruthlessly delineated hierarchy.

Amid the satire and exaggerated portraits of provincial ‘jobsworths’ there are darker moments, such as the descriptions of rampant misogyny, genuine poverty among the working classes, and the very real chance that the women who filled shells and crafted munitions – day in, day out – were in danger of being poisoned by the substances they handled. The determination of the factory managers to keep these problems hidden is chillingly described. These were rotten times for many people in Britain, but if Monica Felton believed that things were being done differently in North Korea or the USSR, then I am afraid she was sadly deluded.

The social observation and political polemic is shot through with several touches or romance, some tragedy, and the mystery of who Griselda Green really is. What is a poised, educated and well-spoken young woman doing among the down-to-earth working class girls filling shells and priming fuzes?

My only major criticism of this book is that it’s perhaps 100 pages too long. The many acerbic, perceptive and quotable passages – mostly Felton’s views on the more nonsensical aspects of British society – tend to fizz around like shooting stars in an otherwise dull grey sky.

Is it worth reading? Yes, of course, but you must be prepared for many pages of Ms Felton being on communist party message interspersed with passages of genuinely fine writing. To All The Living is published by the Imperial War Museum, and is out now.