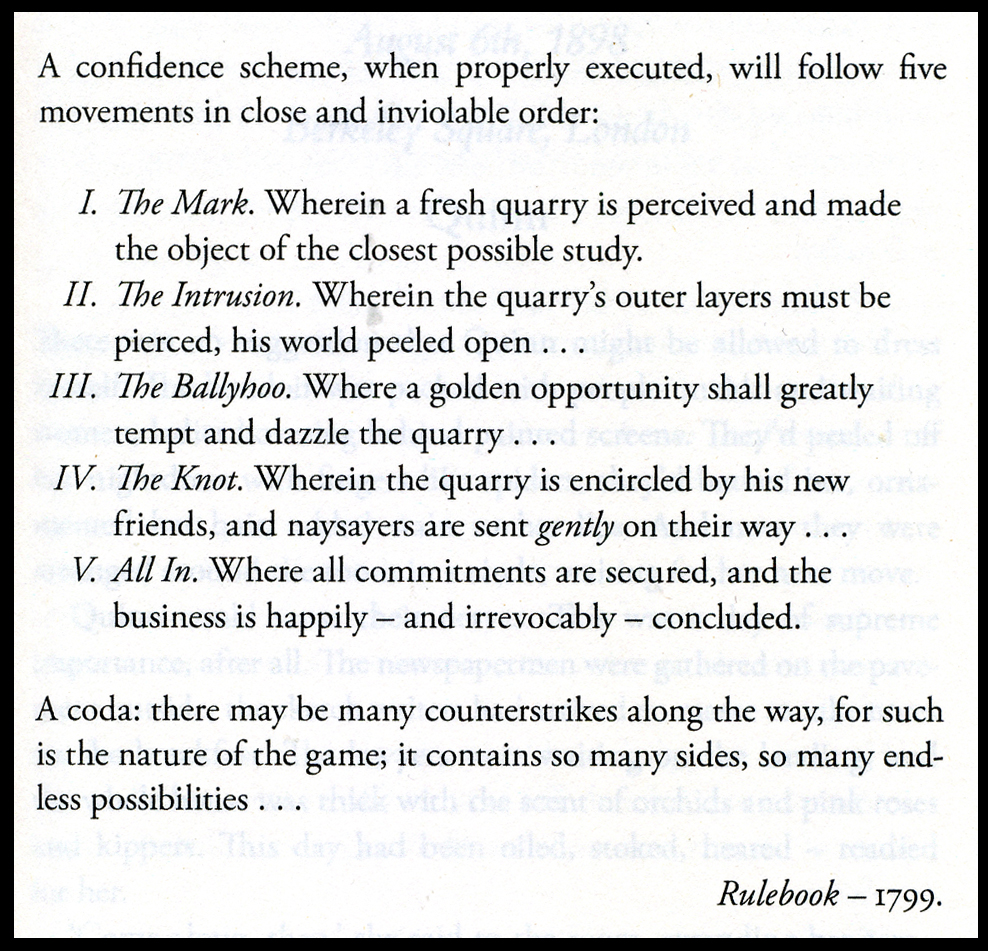

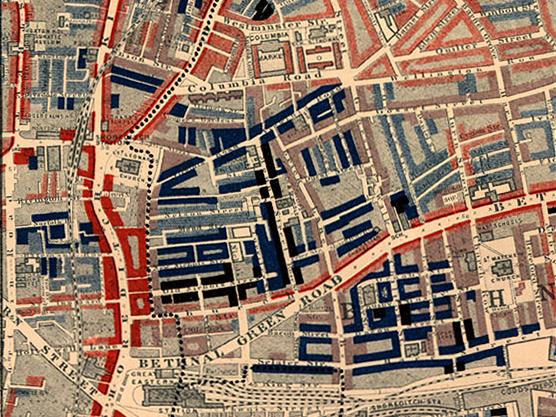

Alex Hay spins a yarn that is a preposterous as they come, but the more audacious the schemes of Quinn le Blanc become, the more entertainment the book provides. Quinn is a confidence trickster, dedicated to separating fools and their fortunes. Her home is a house in Spitalfields, and we are in the last years of Queen Victoria’s reign, a full ten years since the streets and alleys near le Blanc’s house echoed with the cries of “murder!” as yet another lady of the night was struck down by Britain’s most infamous serial killer. I may be be wrong, but the author may be giving a nod to Victorian theatre techniques, and the ability of its writers and directors to fool audiences with special effects. These, superbly described in The Fascination, by Essie Fox, are from a time long before CGI and earlier studio fakery. Le Blanc has one task. In five days, she has to meet and snare one of London’s most eligible bachelors, Max Kendal. He is alleged to be improbably wealthy, but possibly a case of ‘asset rich, cash poor.’ With the aid of Mrs Airlie, a refined former fraudster, she prepares to set her trap. The ‘Fives’ in the book’s title refers to a kind of protocol which has five separate stages to guide the potential fraudster.

Quinn receives a surprise invitation to the Duke’s ball, but she is suspicious:

“Quinn could smell it: the scent of the game, sweet and rotten. She didn’t trust the Duke, didn’t trust this card. She needed to find out what exactly he was concealing. The serpent was uncoiling in her heart.”

Being a high class female confidence trickster is not just a matter of desire, deception and decolletage. Quinn has to be able to do the kind of small talk the woman she was impersonating would be comfortable with. At the Duke’s ball:

“Yes, she was entranced by hunting, shooting, fishing, riding, stalking, hymns, cows,, dogs, lakes, children, her dear- departed parents, embroidery, automobiles and English beef.”

By the time Quinn has worked her way to the third stage of the scheme – The Ballyhoo – Alex Hay has made us aware that there is at least one other player in the game who intends nothing but malice and and disruption to Quinn’s plans. This mysterious person is introduced as The Man in the Blue Silk Waistcoat, but they clearly have shape shifting powers when they metamorphose into The Woman in the Cream Silk Gown. This person is not the only challenge facing Quinn. Victoria – Tor- Kendal, Max’s sister, is a force of nature. She is unconventional and a sexual predator, but her main concern is for her own fortunes should Max marry. The siblings’ stepmother, Lady Kendal is deceptively demure, but beneath her lightweight airs and graces is a formidable intelligence and steely self-will.

“There was something impenetrable about Lady Kendall. Something opaque, as if her roots had been dug deep, deep into the ground. She gave the outward impression of perfect, doll-like refinement, but there was absolute strength there.”

Alex Hay eventually lets us know the identity of the mysterious shape-shifter who is determined to sabotage Quinn’s attempt to snare the Duke and his fortune. Then, in a delicious twist, we learn that the Duke’s apparent sincerity regarding a marriage is just as insubstantial as that of Quinn. Not to spoil the fun, but I can’t resist a little teaser. If you recognise these lines, then you will know what is going on.

“He sipped at a weak hock and seltzer

As he gazed at the London skies”

Throughout the novel, the prose is rich, florid, and decidedly decadent – totally appropriate to what cultural historians have termed the ‘fin de siècle’, a period of dramatic contrasts between rich and poor, morally indulgent and haunted by the ghosts of Swinburne, Wilde, Beardsley, Verlaine and Sickert. The wedding breakfast prior to the marriage of Quinn and Max is wonderfully grotesque. Hieronymus Bosch had been dead for nearly four centuries, while it would be twenty more years before Otto Dix and George Grosz assaulted bourgeois sensibilities with their savage cartoons. Alex Hay trumps them all:

“Around them, the footmen were placing mountains of food upon the table. Collared eels, roast fowl, slabs of tongue, joints of beef, biscuits, wafers, ices, cream and water. The mayonnaise shuddered, glutinous and sick-making. Everything smelled taut, stewed, drenched in vinegar.”

This is a wonderful example of how a spectacularly good novel does not have to feature characters with whom we claim moral kinship. Quinn is simply awful – an unscrupulous predator with the moral compass of a centipede. Tor Kendal is a narcissistic ‘problem child’ with zero awareness of social or human sensibilities. Perhaps the closest to being a ‘good chap’ is Duke Maximilian, but it is not easy to decide if he is “nice but dim” or just another player in the brutal chess game played by the minor nobility in late Victorian England. This is a terrific read which assaults our senses with descriptions of the more bizarre aspects of English social life in the dying years of the 19th century. Best of all, it has gyroscopic plot which spins on its own axis innumerable times before Alex Hay persuades us that it all makes sense. Published by Headline Review The Queen of Fives is available now.

We are in London in the summer of 1879, and young Holmes has yet to meet the man who will write up his greatest cases. Holmes works for a guinea a day, and is striving to build his reputation. Within the first few pages, he has been hired to investigate two cases on behalf of a man who was already a celebrity, and another who would become infamous in his lifetime, but revered and admired after his death. The celebrity is Albert Edward, Prince of Wales, the future King Edward VII, a notorious Lothario whose battleground has been country houses and mansions the length and breadth of the country, the vanquished being a long list of cuckolded husbands. It seems that the heir to the throne has been in the habit of entering his sexual achievements in a diary – a kind of fornicator’s Bradshaw, if you will – but it has gone missing, and Holmes is charged with recovering it.

We are in London in the summer of 1879, and young Holmes has yet to meet the man who will write up his greatest cases. Holmes works for a guinea a day, and is striving to build his reputation. Within the first few pages, he has been hired to investigate two cases on behalf of a man who was already a celebrity, and another who would become infamous in his lifetime, but revered and admired after his death. The celebrity is Albert Edward, Prince of Wales, the future King Edward VII, a notorious Lothario whose battleground has been country houses and mansions the length and breadth of the country, the vanquished being a long list of cuckolded husbands. It seems that the heir to the throne has been in the habit of entering his sexual achievements in a diary – a kind of fornicator’s Bradshaw, if you will – but it has gone missing, and Holmes is charged with recovering it. One hundred pages in, and it is clear that the author is enjoying a glorious exercise in name-dropping. James McNeill Whistler, Lillie Langtry, Francis Knollys, Patsy Cornwallis-West, Frank Miles, Sarah Bernhardt, John Everett Millais and Rosa Corder (right) are just a few of the real life characters who make an appearance, and it is clear that ‘Sherlock Holmes’ moves in very elegant circles.

One hundred pages in, and it is clear that the author is enjoying a glorious exercise in name-dropping. James McNeill Whistler, Lillie Langtry, Francis Knollys, Patsy Cornwallis-West, Frank Miles, Sarah Bernhardt, John Everett Millais and Rosa Corder (right) are just a few of the real life characters who make an appearance, and it is clear that ‘Sherlock Holmes’ moves in very elegant circles.

*

*

s she gazes up at her bedroom ceiling, Lily Bell daydreams of becoming an actress. She is, to be sure, beautiful enough, with her long almost-white blond hair and her flawless complexion, but for the stepdaughter of a struggling artist in the London of 1851, her dreams of becoming Ophelia, Juliet or Desdemona are just foolish fantasies. Until the day her penniless stepfather receives a visit from one of his creditors, a mysterious self-styled Professor – Erasmus Salt. Salt is actually a theatrical showman, with a macabre interest in that overwhelming Victorian obsession, communicating with the dead. He offers Alfred Bell respite from the debt in return for Lily accompanying Salt and his spinster sister Faye to become the star of a new production, in which he will convince audiences that he has raised the dead.

s she gazes up at her bedroom ceiling, Lily Bell daydreams of becoming an actress. She is, to be sure, beautiful enough, with her long almost-white blond hair and her flawless complexion, but for the stepdaughter of a struggling artist in the London of 1851, her dreams of becoming Ophelia, Juliet or Desdemona are just foolish fantasies. Until the day her penniless stepfather receives a visit from one of his creditors, a mysterious self-styled Professor – Erasmus Salt. Salt is actually a theatrical showman, with a macabre interest in that overwhelming Victorian obsession, communicating with the dead. He offers Alfred Bell respite from the debt in return for Lily accompanying Salt and his spinster sister Faye to become the star of a new production, in which he will convince audiences that he has raised the dead. Despite her misgivings, Lily is intrigued by what appears to be a chance to achieve her ambition. After all, Salt’s theatrical illusion may be faintly sinister, but who knows what career doors it might unlock? Bell, despite the tears and misgivings of his wife, cannot get Lily out of the door fast enough, and soon the girl is on her way south, to the seaside town of Ramsgate, where Salt’s production is due to be presented at The New Tivoli theatre.

Despite her misgivings, Lily is intrigued by what appears to be a chance to achieve her ambition. After all, Salt’s theatrical illusion may be faintly sinister, but who knows what career doors it might unlock? Bell, despite the tears and misgivings of his wife, cannot get Lily out of the door fast enough, and soon the girl is on her way south, to the seaside town of Ramsgate, where Salt’s production is due to be presented at The New Tivoli theatre. y now we, as readers, know much more about Salt than does the hapless Lily. Having experience a terrible trauma in his youth, the balance of his mind has been disturbed; he may also be a murderer, and his obsession with the dead could be leading further than simply the creation of a melodramatic theatrical illusion.

y now we, as readers, know much more about Salt than does the hapless Lily. Having experience a terrible trauma in his youth, the balance of his mind has been disturbed; he may also be a murderer, and his obsession with the dead could be leading further than simply the creation of a melodramatic theatrical illusion.

Harper lives above a city pub, the Victoria. His wife, Annabelle, is the landlady, but she is also a fiercely determined advocate of women’s rights, and she has made waves by being elected to the local Board of Guardians, a largely male-dominated organisation which is tasked with administering what, in the dying years of Queen Victoria’s reign, passed for social care. When the brother of Harper’s one-time colleague, Billy Reed, commits suicide the death is dismissed, albeit sadly, as commonplace, but Reed believes that his brother’s death is due to something more sinister, and he asks Harper to investigate.

Harper lives above a city pub, the Victoria. His wife, Annabelle, is the landlady, but she is also a fiercely determined advocate of women’s rights, and she has made waves by being elected to the local Board of Guardians, a largely male-dominated organisation which is tasked with administering what, in the dying years of Queen Victoria’s reign, passed for social care. When the brother of Harper’s one-time colleague, Billy Reed, commits suicide the death is dismissed, albeit sadly, as commonplace, but Reed believes that his brother’s death is due to something more sinister, and he asks Harper to investigate.

Outraged leading articles appear in local newspapers, but someone believes that the sword – or something equally violent – is mightier than the pen, and a homemade bomb destroys a church hall just before Annabelle Harper is due to speak to her supporters. The caretaker is tragically killed by the explosion, and matters go from bad to worse when more bombs are found, and several of the women candidates are threatened.

Outraged leading articles appear in local newspapers, but someone believes that the sword – or something equally violent – is mightier than the pen, and a homemade bomb destroys a church hall just before Annabelle Harper is due to speak to her supporters. The caretaker is tragically killed by the explosion, and matters go from bad to worse when more bombs are found, and several of the women candidates are threatened.

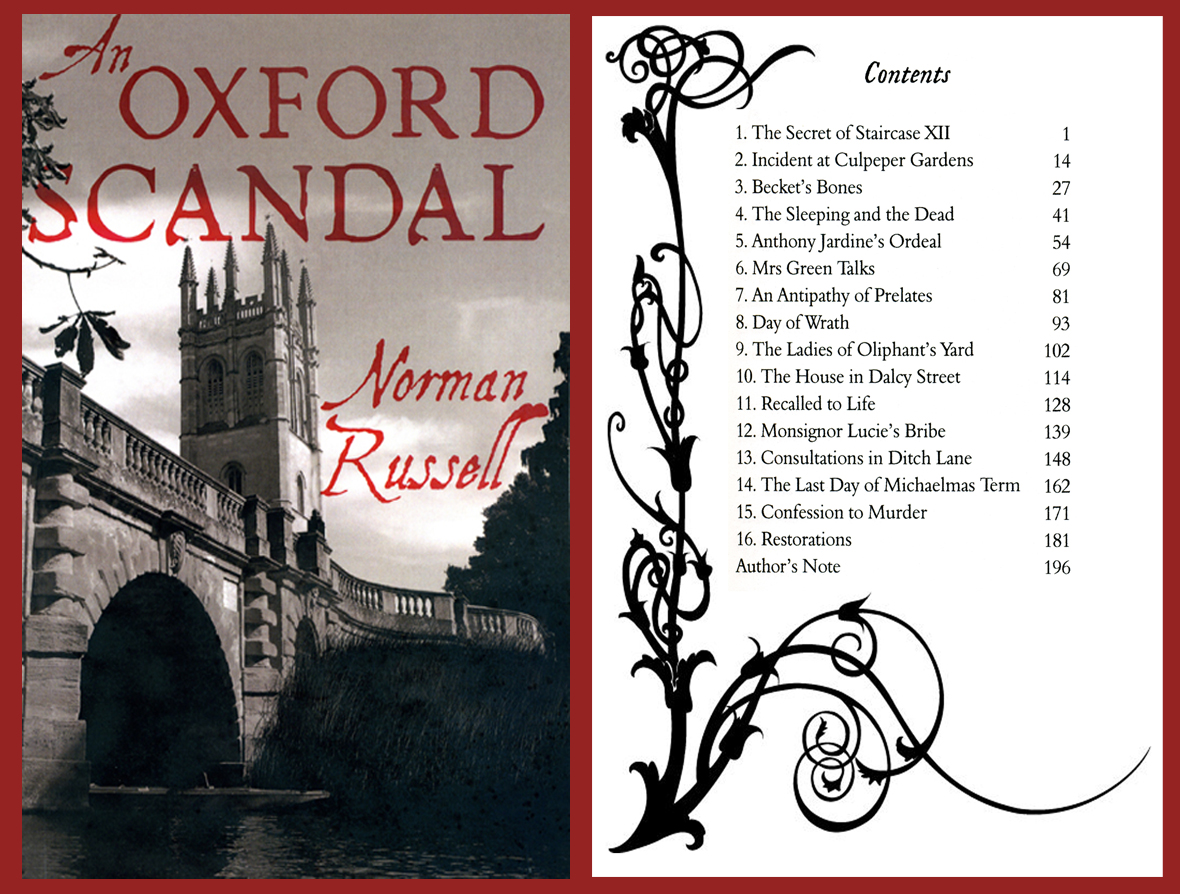

Oxford, 1895. The spires may well be dreaming, but for Anthony Jardine, Fellow of St Gabriel’s College, the nightmare is just beginning. His drug addicted wife is found stabbed to death, slumped in the corner of a horse tram carriage. His mourning is shattered when his mistress is also found dead – murdered in the house she shares with her elderly eccentric husband. With a background story of an archaeological discovery threatening to shake the English religious establishment to its very roots, Inspector James Antrobus must avoid the temptation to make Jardine a swift and easy culprit. Helped by the uncanny perception of Sophia Jex-Blake, a pioneering woman doctor, Antrobus finds the answer to the killings lies in London, just forty miles away on the railway.

Oxford, 1895. The spires may well be dreaming, but for Anthony Jardine, Fellow of St Gabriel’s College, the nightmare is just beginning. His drug addicted wife is found stabbed to death, slumped in the corner of a horse tram carriage. His mourning is shattered when his mistress is also found dead – murdered in the house she shares with her elderly eccentric husband. With a background story of an archaeological discovery threatening to shake the English religious establishment to its very roots, Inspector James Antrobus must avoid the temptation to make Jardine a swift and easy culprit. Helped by the uncanny perception of Sophia Jex-Blake, a pioneering woman doctor, Antrobus finds the answer to the killings lies in London, just forty miles away on the railway. Norman Russell (right) is a writer and academic, who has had fifteen novels published. He is an acknowledged authority on Victorian finance and its reflections in the literature of the period, and his book on the subject, The Novelist and Mammon, was published by Oxford University Press in 1986. He is a graduate of Oxford and London Universities. After military service in the West Indies, he became a teacher of English in a large Liverpool comprehensive school, where he stayed for twenty-six years, retiring early to take up writing as a second career.

Norman Russell (right) is a writer and academic, who has had fifteen novels published. He is an acknowledged authority on Victorian finance and its reflections in the literature of the period, and his book on the subject, The Novelist and Mammon, was published by Oxford University Press in 1986. He is a graduate of Oxford and London Universities. After military service in the West Indies, he became a teacher of English in a large Liverpool comprehensive school, where he stayed for twenty-six years, retiring early to take up writing as a second career.