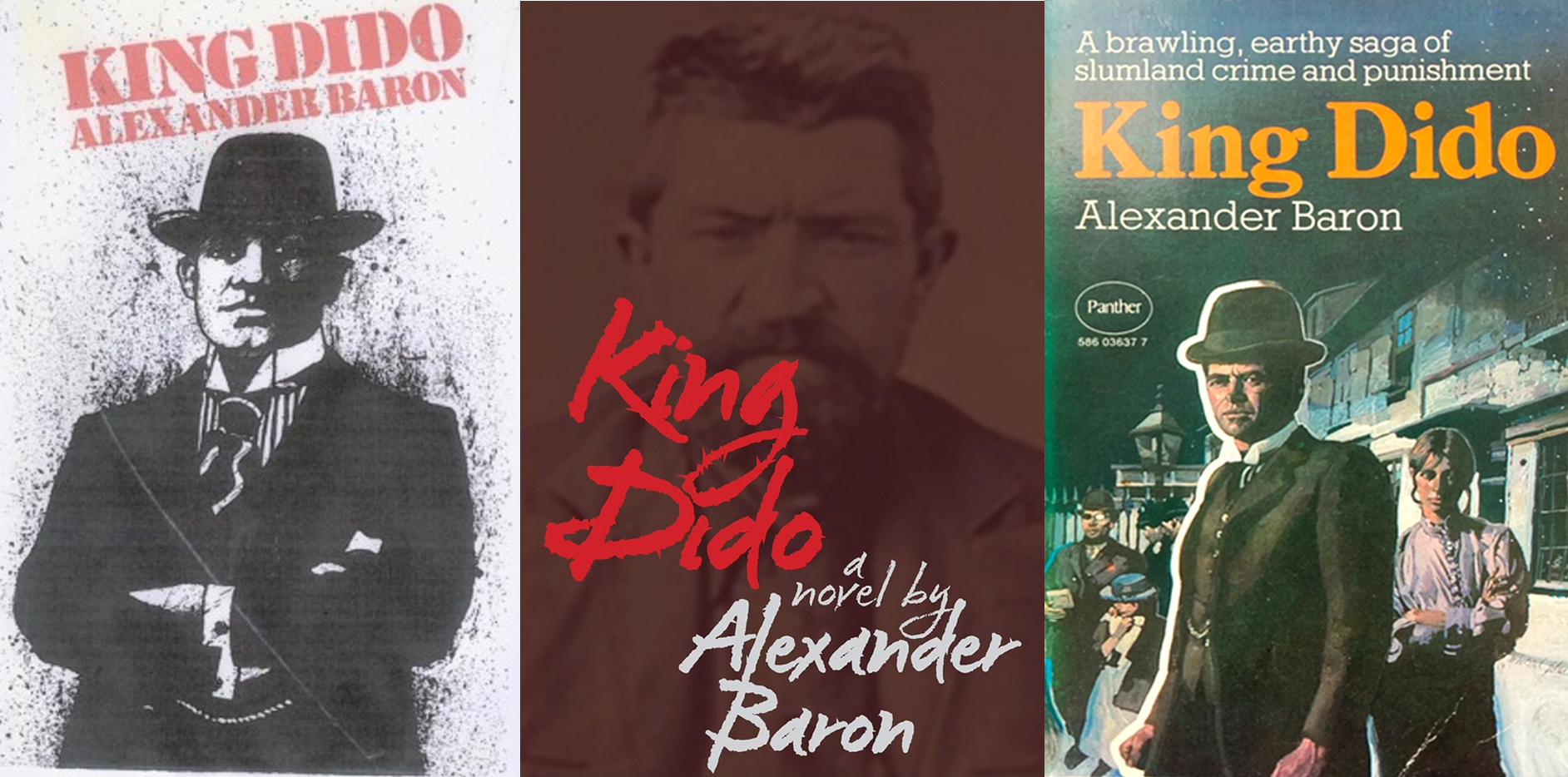

Alexander Baron (1917 – 1999) is a writer who has returned to the consciousness of the reading public in recent times because the Imperial War Museum have republished his two classic WW2 novels From The City, From The Plough, There’s No Home, and the third in the trilogy, the collection of short stories The Human KInd. His compassion and his acute awareness of the highs and lows of men and women at war have embedded the trilogy into the culture of WW2, just as the poems of Owen, Sassoon and Gurney are inescapably linked with The Great War. King Dido (1969) is a book of a very different kind.

We are in the East End of London, and it is the summer of 1911, not long after the coronation of King George V and Queen Mary. Dido is, by trade, a dock worker but, after a violent encounter with the district’s 1911 version of the Krays, he takes over the streets and becomes a kind of Reg. Not Ron, because Dido is not a psychopath, but the ‘tributes’ he collects make him a decent living. After a turbulent back alley encounter with a young waitress called Grace, Dido does ‘right thing’ and marries her. They live in redecorated rooms above the rag recovery business Dido’s mother runs. There has been a trend in crime fiction in recent years, which I call ‘anxiety porn’, but it is nothing new. More politely, these are known as ‘domestic thrillers.’ Mostly, they describe perfectly ordinary people whose lives gradually disintegrate, not through epic events, but because normal social tensions, misunderstandings, misplaced ambitions and tricks of fate turn their lives upside down. So it is here. Grace, blissfully unaware of how Dido earns his money, tries to put her feet on the next series of rungs in the ladder that leads to gentrification. However, the family’s journey on the board game of life becomes, via the snakes, a downward one, and it is a painful descent.

Baron grew up as Joseph Alexander Bernstein in Hackney, but he was actually born In Maidenhead, his mother having been evacuated there as a result of Zeppelin raids on London. His father was a master furrier, so it is clear that there is nothing autobiographical about his characterisation of Dido Peach. What is evident in the book is that Baron was aware of the existence of subtle strata within the East End poor. By 1911 the Huguenots had long since moved away, leaving such places as Christ Church Spitalfields and the elegant houses in Fournier Street as their memorials. There remained what could be called the ‘dirt’ poor, and then the ‘genteel’ poor – such as Mrs Peach and her family. What doesn’t feature in the novel, but was exactly contemporaneous, was the upsurge in activity by Eastern European activists, mostly exiles from Russia. The Houndsditch Murders and the resultant Siege of Sidney Street was that same year, while The Tottenham Outrage had been two years earlier. Both events remain writ large in East End history.

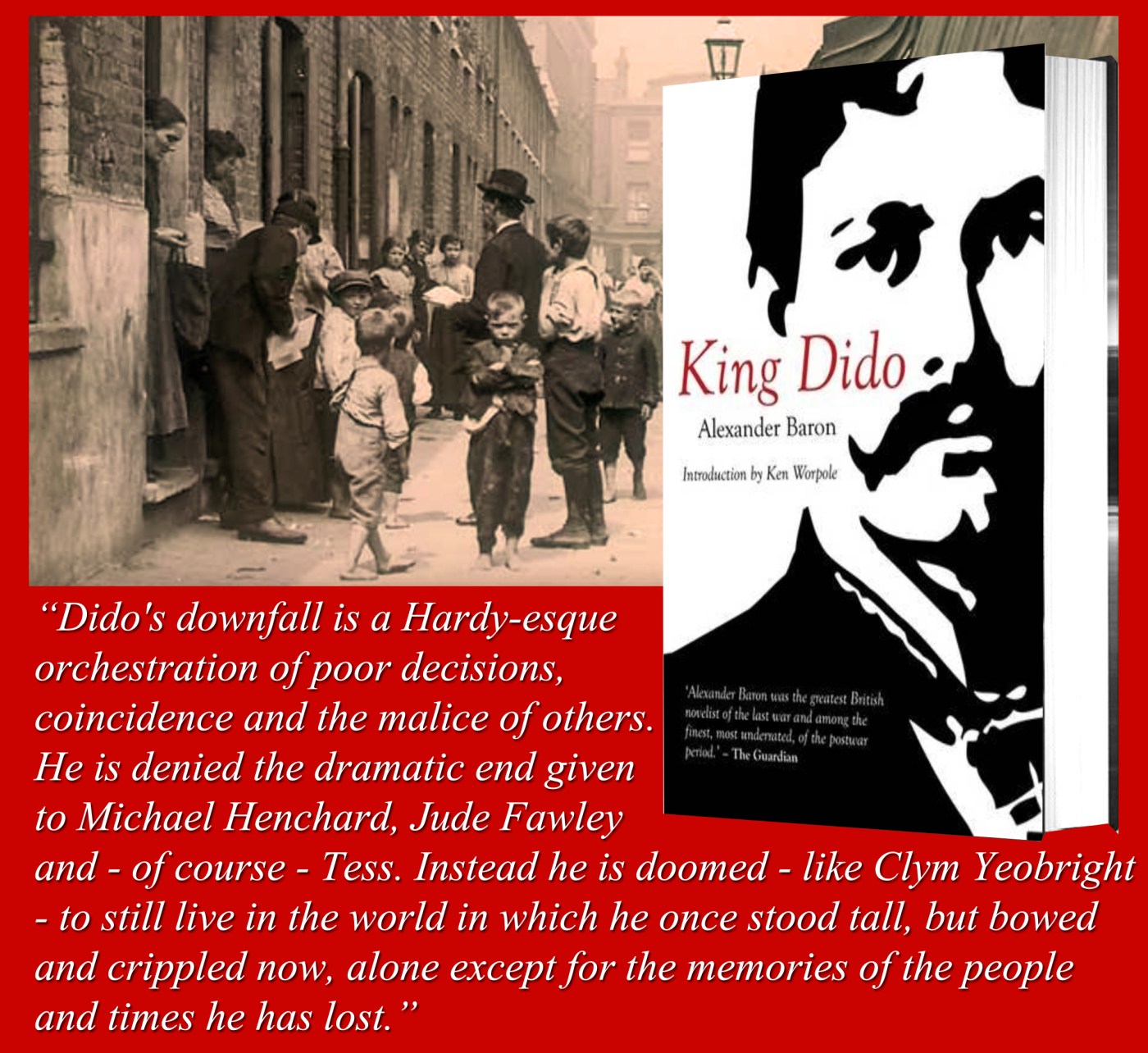

In the end, Dido’s downfall is a Hardy-esque orchestration of poor decisions, coincidence and the malice of others. He is denied the dramatic end given to Michael Henchard, Jude Fawley and – of course – Tess. Instead he is doomed – like Clym Yeobright – to still live in the world in which he once stood tall, but bowed and crippled now, alone except for the memories of the people and times he has lost. Baron’s prose here, just as in his better known books, is vivid, clear and full of insights.

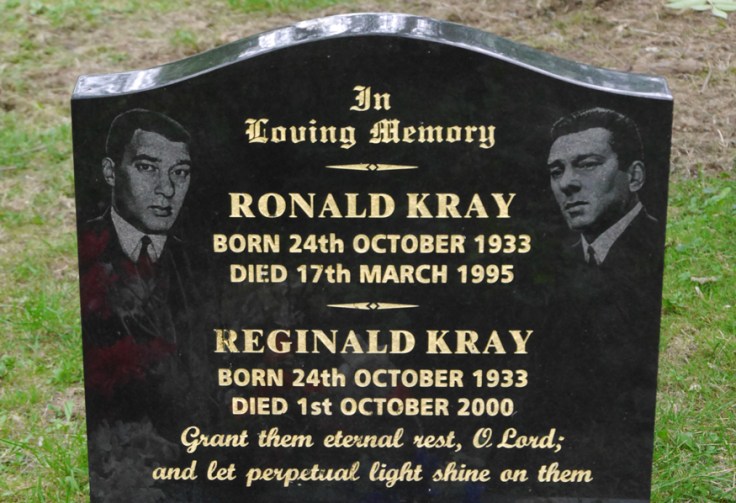

REGGIE AND RONNIE KRAY have been the subject of almost as many books, documentaries and dramas as their 19th century near-neighbour Jack the Ripper. The East End that he – whoever he was – knew has changed almost beyond recognition. The Bethnal Green of the Krays is heading in the same direction, but a few landmarks remain unscathed. They were born out in Hoxton in October 1933, Reggie being the older by ten minutes. The family moved into Bethnal Green in 1938, and they lived at 178 Vallance Road. That house no longer stands, modern houses having been built on the site (left)

REGGIE AND RONNIE KRAY have been the subject of almost as many books, documentaries and dramas as their 19th century near-neighbour Jack the Ripper. The East End that he – whoever he was – knew has changed almost beyond recognition. The Bethnal Green of the Krays is heading in the same direction, but a few landmarks remain unscathed. They were born out in Hoxton in October 1933, Reggie being the older by ten minutes. The family moved into Bethnal Green in 1938, and they lived at 178 Vallance Road. That house no longer stands, modern houses having been built on the site (left)

George Cornell (right) had known the twins from childhood. Their careers had developed more or less on similar lines, except that Cornell became the enforcer for the Richardsons. On 7th March 1966 there was a confused shoot-out at a club in Catford. Members of the Kray gang and the Richardsons gang were involved. At some point, George Cornell had been heard to refer to Ronnie Kray as a “fat poof.” That might seem unkind, but was not totally inaccurate. Ronnie was certainly plumper than his lean and hungry twin, and his liking for handsome boys was well known.

George Cornell (right) had known the twins from childhood. Their careers had developed more or less on similar lines, except that Cornell became the enforcer for the Richardsons. On 7th March 1966 there was a confused shoot-out at a club in Catford. Members of the Kray gang and the Richardsons gang were involved. At some point, George Cornell had been heard to refer to Ronnie Kray as a “fat poof.” That might seem unkind, but was not totally inaccurate. Ronnie was certainly plumper than his lean and hungry twin, and his liking for handsome boys was well known. On the evening of 9th March, Cornell and an associate were unwise enough to call in for a drink at a The Blind Beggar pub on Whitechapel Road, very much in Kray territory. Some thoughtful soul telephoned Ronnie Kray, who was drinking in a nearby pub, The Lion in Tapp Street (left). Ronnie, pausing only to collect a handgun made straight for the Blind Beggar, strode in, and shot George Cornell in the head at close range. His death was almost instantaneous. Needless to say, no-one else in the pub had seen anything. Pictured below are a post mortem photograph of Cornell, and the bloodstained floor of The Blind Beggar. Below that is the fatal pub, then and now.

On the evening of 9th March, Cornell and an associate were unwise enough to call in for a drink at a The Blind Beggar pub on Whitechapel Road, very much in Kray territory. Some thoughtful soul telephoned Ronnie Kray, who was drinking in a nearby pub, The Lion in Tapp Street (left). Ronnie, pausing only to collect a handgun made straight for the Blind Beggar, strode in, and shot George Cornell in the head at close range. His death was almost instantaneous. Needless to say, no-one else in the pub had seen anything. Pictured below are a post mortem photograph of Cornell, and the bloodstained floor of The Blind Beggar. Below that is the fatal pub, then and now.

Folklore has it that now that Ronnie had ‘done the big one’, there was pressure on Reggie to match his twin’s achievement. The chance was over a year in coming. Jack McVitie (right) was a drug addicted criminal enforcer who worked, on and off, for the Krays. His nickname ‘The Hat’ was because he was embarrassed about his thinning hair, and always wore a trademark trilby. McVitie had taken £500 from the Krays to kill someone, had botched the job, but kept the money. He had also, unwisely,been heard to bad-mouth the twins.

Folklore has it that now that Ronnie had ‘done the big one’, there was pressure on Reggie to match his twin’s achievement. The chance was over a year in coming. Jack McVitie (right) was a drug addicted criminal enforcer who worked, on and off, for the Krays. His nickname ‘The Hat’ was because he was embarrassed about his thinning hair, and always wore a trademark trilby. McVitie had taken £500 from the Krays to kill someone, had botched the job, but kept the money. He had also, unwisely,been heard to bad-mouth the twins. On the night of 29th October 1967, McVitie was lured to a basement flat in Evering Road, Stoke Newington,(left) on the pretext of a party. There, he was met by Reggie Kray and other members of the firm. Kray’s attempt to shoot McVitie misfired – literally – and instead, he stabbed McVitie repeatedly with a carving knife. McVitie’s body was never found, and the stories about his eventual resting place range from his being fed to the fishes of the Sussex coast to being buried incognito in a Gravesend cemetery.

On the night of 29th October 1967, McVitie was lured to a basement flat in Evering Road, Stoke Newington,(left) on the pretext of a party. There, he was met by Reggie Kray and other members of the firm. Kray’s attempt to shoot McVitie misfired – literally – and instead, he stabbed McVitie repeatedly with a carving knife. McVitie’s body was never found, and the stories about his eventual resting place range from his being fed to the fishes of the Sussex coast to being buried incognito in a Gravesend cemetery.