Greg Iles was born in Stuttgart where his father ran the US Embassy medical clinic. When the family returned to the States they settled in Natchez, Mississippi. While studying at the University of Mississippi in Oxford, Iles stayed in a cottage where Caroline ‘Callie’ Barr Clark once lived. Callie was William Faulkner’s ‘Mammy Callie’ and different versions of her appear in several of Faulkner’s books. Iles began writing novels in 1993, with a historical saga about the enigmatic Nazi Rudolf Hess, and has written many stand-alone thrillers, but it is his epic trilogy of novels set in Natchez which, in my view, set him apart from anyone else who has ever written in the Southern Noir genre.

Greg Iles was born in Stuttgart where his father ran the US Embassy medical clinic. When the family returned to the States they settled in Natchez, Mississippi. While studying at the University of Mississippi in Oxford, Iles stayed in a cottage where Caroline ‘Callie’ Barr Clark once lived. Callie was William Faulkner’s ‘Mammy Callie’ and different versions of her appear in several of Faulkner’s books. Iles began writing novels in 1993, with a historical saga about the enigmatic Nazi Rudolf Hess, and has written many stand-alone thrillers, but it is his epic trilogy of novels set in Natchez which, in my view, set him apart from anyone else who has ever written in the Southern Noir genre.

Natchez, Mississippi. Just under 16,000 souls. A small town with a big history. It perches on a bluff above the Mississippi River, and some folk reckon they can still hear the ghosts of paddle steamers chunking away down there on the swirling brown waters. The central character in Natchez Burning, The Bone Tree and Mississippi Blood is Penn Cage. Cage is the classic enlightened white liberal character of Southern Noir. His background is privileged; his father, Tom, is a doctor who is hugely respected by the black community in the area for his colour blind approach to his vocation. Medical bills too numerous to mention have been written off over the years, and Cage senior is the closest thing to a living saint but, of course, he is regarded with a mixture of fear, distrust and loathing by Natchez residents who still hang portraits of Robert E Lee and Nathan Bedford Forrest in their hallways. Penn says of him:

enn Cage, though, has made his own money. He is a hugely successful author, long-time DA for the County and now, after a bitter political struggle, The Mayor of Natchez. He has made many enemies in his rise to fame, not the least of which are the corrupt Sheriff Byrd and the deeply ambitious and oleaginous public prosecutor Shadrach Johnson. Cage is not without his own ghosts, however, and he is haunted by the death of his wife Sarah, crippled and then tortured by cancer. He has, however, established an unofficial second marriage with the campaigning journalist, Caitlin Masters.

enn Cage, though, has made his own money. He is a hugely successful author, long-time DA for the County and now, after a bitter political struggle, The Mayor of Natchez. He has made many enemies in his rise to fame, not the least of which are the corrupt Sheriff Byrd and the deeply ambitious and oleaginous public prosecutor Shadrach Johnson. Cage is not without his own ghosts, however, and he is haunted by the death of his wife Sarah, crippled and then tortured by cancer. He has, however, established an unofficial second marriage with the campaigning journalist, Caitlin Masters.

The politically correct and socially comfortable world inhabited by Penn Cage and his family is about to suffer a brutal invasion. Hidden deep at the end of the rutted dirt road which leads away from the relatively polite discourse between liberals and conservatives in Natchez society, is a dark and dangerous place occupied by a group of men known as the Double Eagles. They are united by a bitterness provoked by their view that the Ku Klux Klan went soft. Their anger, however, was not limited to tearful and rancorous drinking sessions around some backwoods table, but was the match that lit the gunpowder trail to a devastating explosion of focused violence which resulted in the assassinations of the three Ks – Kennedy, Kennedy – and King.

f course, Iles takes a great risk here. We know – or think we know – who killed these three men. But do we? Iles is confident and fluent enough to turn history on its head and present a credible alternative truth. While the Double Eagles are concerned with matters of national importance, they also have time for vicious local issues. The bombshell which threatens to reduce to ruins the cosy edifice of the Cage family, is that Tom Cage fell in love with a black nurse who worked for him, fathered a son by her, but then sat back and watched as she fled north to Chicago in disgrace. When she returns to Natchez to die, riddled by cancer, what she and Tom Cage knew – and did – about the malevolent Double Eagles back in the day becomes a public shit-storm.

f course, Iles takes a great risk here. We know – or think we know – who killed these three men. But do we? Iles is confident and fluent enough to turn history on its head and present a credible alternative truth. While the Double Eagles are concerned with matters of national importance, they also have time for vicious local issues. The bombshell which threatens to reduce to ruins the cosy edifice of the Cage family, is that Tom Cage fell in love with a black nurse who worked for him, fathered a son by her, but then sat back and watched as she fled north to Chicago in disgrace. When she returns to Natchez to die, riddled by cancer, what she and Tom Cage knew – and did – about the malevolent Double Eagles back in the day becomes a public shit-storm.

The Bone Tree is a terrible place. Deep in a snake and gator-infested swamp it is an ancient cypress tree where generations of slave owners and white supremacists have taken their black victims and executed them, For Tom Cage’s nurse, Viola Turner, it is a place of nightmares, because under its rotten and gnarled branches her brother was tortured, mutilated and executed.

Tom Cage is accused of mercy killing Viola. Unwilling to face the public disgrace, he goes on te run with a couple of a trusted former Korean War buddy, and they outwit the authorities for a time. Eventually, Tom Cage is captured and put on trial for murder. He refuses the help of his son and, instead, relies on the charismatic courtroom presence of Quentin Avery, a celebrated black lawyer. Mississippi Blood contains one of the best courtroom scenes I have ever read. I realise this feature is 700 words in with not a critical word, but each of the three novels is a lengthy read by any standards, being well north of 600 pages in each case.

o why are the books so good? Penn Cage is a brilliant central character and, of course, he is politically, morally and socially ‘a good man’. His personal tragedies evoke sympathy, but also provide impetus for the things he says and does. Some might criticise the lack of nuance in the novels; there is no moral ambiguity – characters are either venomous white racists or altruistic liberals. Maybe the real South isn’t that simple; perhaps there are white communities who are blameless and tolerant and shrink in revulsion from dark deeds committed by fearsome ex-military psychopaths who seek to restore a natural order that died a century earlier.

o why are the books so good? Penn Cage is a brilliant central character and, of course, he is politically, morally and socially ‘a good man’. His personal tragedies evoke sympathy, but also provide impetus for the things he says and does. Some might criticise the lack of nuance in the novels; there is no moral ambiguity – characters are either venomous white racists or altruistic liberals. Maybe the real South isn’t that simple; perhaps there are white communities who are blameless and tolerant and shrink in revulsion from dark deeds committed by fearsome ex-military psychopaths who seek to restore a natural order that died a century earlier.

The world of crime fiction – peopled by writers. readers, publishers and critics – is overwhelmingly progressive, liberal minded and sympathetic to persecuted minorities, and so it should be. It is probably just as well, however, that embittered, dispossessed and marginalised white communities in Mississippi, Texas. Louisiana and other heartlands of The South are not great CriFi readers. Penn Cage fights a battle that definitely needs fighting. Greg Iles has given Cage a voice, and has written a majestic trilogy which sets in stone the chapter and verse about generations of Southern people whose hands drip blood and guilt in equal measure. Maybe the moral perspective is very one-sided, and perhaps the books pose as many questions as they answer, but for sheer readability, authenticity and narrative drive, Natchez Burning, The Bone Tree and Mississippi Blood have laid down a literary challenge which will probably never be answered.

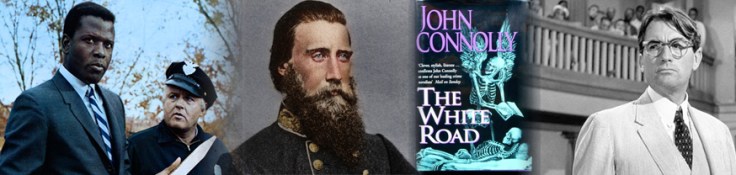

he racial element in South-set crime fiction over the last half century is peculiar in the sense that there have been few, if any, memorable black villains. There are plenty of bad black people in Walter Mosley’s novels, but then most of the characters in them are black, and they are not set in what are, for the purposes of this feature, our southern heartlands.

he racial element in South-set crime fiction over the last half century is peculiar in the sense that there have been few, if any, memorable black villains. There are plenty of bad black people in Walter Mosley’s novels, but then most of the characters in them are black, and they are not set in what are, for the purposes of this feature, our southern heartlands. Black characters are almost always good cops or PIs themselves, like Virgil Tibbs in John Ball’s In The Heat of The Night (1965), or they are victims of white oppression. In the latter case there is often a white person, educated and liberal in outlook, (prototype Atticus Finch, obviously) who will go to war on their behalf. Sometimes the black character is on the side of the good guys, but intimidating enough not to need help from their white associate. John Connolly’s Charlie Parker books are mostly set in the northern states, but Parker’s dangerous black buddy Louis is at his devastating best in The White Road (2002) where Parker, Louis and Angel are in South Carolina working on the case of a young black man accused of raping and killing his white girlfriend.

Black characters are almost always good cops or PIs themselves, like Virgil Tibbs in John Ball’s In The Heat of The Night (1965), or they are victims of white oppression. In the latter case there is often a white person, educated and liberal in outlook, (prototype Atticus Finch, obviously) who will go to war on their behalf. Sometimes the black character is on the side of the good guys, but intimidating enough not to need help from their white associate. John Connolly’s Charlie Parker books are mostly set in the northern states, but Parker’s dangerous black buddy Louis is at his devastating best in The White Road (2002) where Parker, Louis and Angel are in South Carolina working on the case of a young black man accused of raping and killing his white girlfriend. hosts, either imagined or real, are never far from Charlie Parker, but another fictional cop has more than his fair share of phantoms. James Lee Burke’s Dave Robicheaux frequently goes out to bat for black people in and around New Iberia, Louisiana. Robicheaux’s ghosts are, even when he is sober, usually that of Confederate soldiers who haunt his neighbourhood swamps and bayous. I find this an interesting slant because where John Connolly’s Louis will wreak havoc on a person who happens to have the temerity to sport a Confederate pennant on his car aerial, Robicheaux’s relationship with his CSA spectres is much more subtle.

hosts, either imagined or real, are never far from Charlie Parker, but another fictional cop has more than his fair share of phantoms. James Lee Burke’s Dave Robicheaux frequently goes out to bat for black people in and around New Iberia, Louisiana. Robicheaux’s ghosts are, even when he is sober, usually that of Confederate soldiers who haunt his neighbourhood swamps and bayous. I find this an interesting slant because where John Connolly’s Louis will wreak havoc on a person who happens to have the temerity to sport a Confederate pennant on his car aerial, Robicheaux’s relationship with his CSA spectres is much more subtle.

urke’s Louisiana is both intensely poetic and deeply political. In Robicheaux: You Know My Name he writes:

urke’s Louisiana is both intensely poetic and deeply political. In Robicheaux: You Know My Name he writes: Elsewhere his rage at his own government’s insipid reaction to the devastation of Hurricane Katrina rivals his fury at generations of white people who have bled the life and soul out of the black and Creole population of the Louisian/Texas coastal regions. Sometimes the music he hears is literal, like in Jolie Blon’s Bounce (2002), but at other times it is sombre requiem that only he can hear:

Elsewhere his rage at his own government’s insipid reaction to the devastation of Hurricane Katrina rivals his fury at generations of white people who have bled the life and soul out of the black and Creole population of the Louisian/Texas coastal regions. Sometimes the music he hears is literal, like in Jolie Blon’s Bounce (2002), but at other times it is sombre requiem that only he can hear:

n opening word or three about the taxonomy of some of the crime fiction genres I am investigating in these features. Noir has an urban and cinematic origin – shadows, stark contrasts, neon lights blinking above shadowy streets and, in people terms, the darker reaches of the human psyche. Authors and film makers have always believed that grim thoughts, words and deeds can also lurk beneath quaint thatched roofs, so we then have Rural Noir, but this must exclude the kind of cruelty carried out by a couple of bad apples amid a generally benign village atmosphere. So, no Cosy Crime, even if it is set in the Southern states, such as

n opening word or three about the taxonomy of some of the crime fiction genres I am investigating in these features. Noir has an urban and cinematic origin – shadows, stark contrasts, neon lights blinking above shadowy streets and, in people terms, the darker reaches of the human psyche. Authors and film makers have always believed that grim thoughts, words and deeds can also lurk beneath quaint thatched roofs, so we then have Rural Noir, but this must exclude the kind of cruelty carried out by a couple of bad apples amid a generally benign village atmosphere. So, no Cosy Crime, even if it is set in the Southern states, such as  eal-life rural poverty in the South was by no means confined to former slaves and their descendants. In historical fact, poor white farmers in the Carolinas, for example, were often caught up in a vicious spiral of borrowing from traders and banks against the outcome of their crop; when time came for payback, they were often simply back to zero, or

eal-life rural poverty in the South was by no means confined to former slaves and their descendants. In historical fact, poor white farmers in the Carolinas, for example, were often caught up in a vicious spiral of borrowing from traders and banks against the outcome of their crop; when time came for payback, they were often simply back to zero, or  thrown off the land due to debt. The rich seam of dirt poor and embittered whites who turn to crime in their anger and resentment has been very successfully mined by novelists. Add a touch of fundamentalist Christianity into the pot and we have a truly toxic stew, such as in Wiley Cash’s brilliant

thrown off the land due to debt. The rich seam of dirt poor and embittered whites who turn to crime in their anger and resentment has been very successfully mined by novelists. Add a touch of fundamentalist Christianity into the pot and we have a truly toxic stew, such as in Wiley Cash’s brilliant  Her best known novel,

Her best known novel,

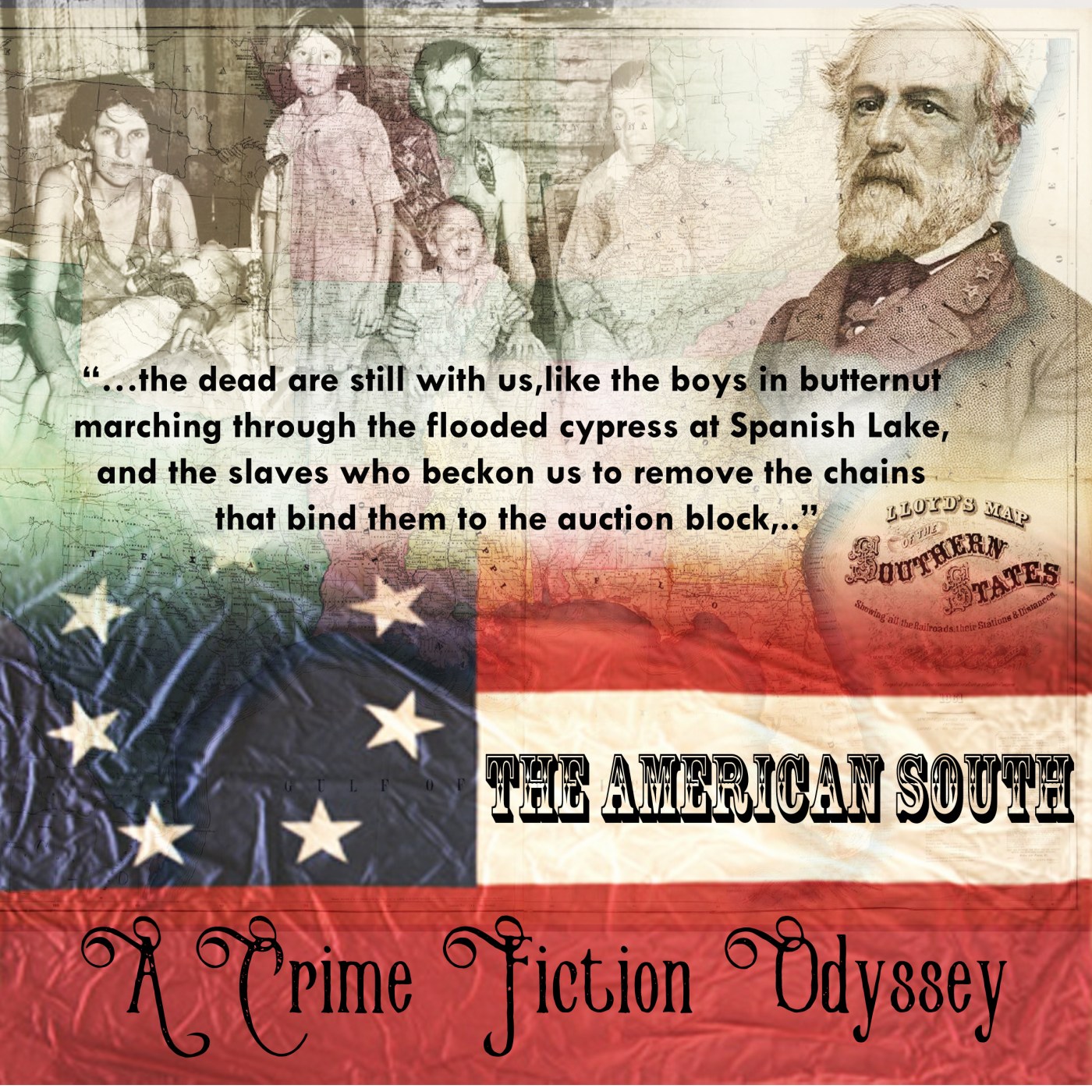

t is starkly obvious to anyone with even a passing knowledge of international history that the most brutal and bitterly fought wars tend to be between factions that have, at least in the eyes of someone looking in from the outside, much in common. No such war anywhere has cast such a long shadow as the American Civil War. That enduring shadow is long, and it is wide. In its breadth it encompasses politics, music, literature, intellectual thought, film and – the purpose of this feature – crime fiction.

t is starkly obvious to anyone with even a passing knowledge of international history that the most brutal and bitterly fought wars tend to be between factions that have, at least in the eyes of someone looking in from the outside, much in common. No such war anywhere has cast such a long shadow as the American Civil War. That enduring shadow is long, and it is wide. In its breadth it encompasses politics, music, literature, intellectual thought, film and – the purpose of this feature – crime fiction. There have been many commentators, critics and writers who have explored the US North-South divide in more depth and with greater erudition than I am able to bring to the table, but I only seek to share personal experience and views. One of my sons lives in Charlotte, North Carolina. It is a very modern city. In the 20th century it was a bustling hive of the cotton milling industry, but as the century wore on it declined in importance. Its revival is due to the fact that at some point in the last thirty years, someone realised that the rents were cheap, transport was good, and that it would be a great place to become a regional centre of the banking and finance industry. Now, the skyscrapers twinkle at night with their implicit message that money is good and life is easy.

There have been many commentators, critics and writers who have explored the US North-South divide in more depth and with greater erudition than I am able to bring to the table, but I only seek to share personal experience and views. One of my sons lives in Charlotte, North Carolina. It is a very modern city. In the 20th century it was a bustling hive of the cotton milling industry, but as the century wore on it declined in importance. Its revival is due to the fact that at some point in the last thirty years, someone realised that the rents were cheap, transport was good, and that it would be a great place to become a regional centre of the banking and finance industry. Now, the skyscrapers twinkle at night with their implicit message that money is good and life is easy. rive out of Charlotte a few miles and you can visit beautifully preserved plantation houses. Some have the imposing classical facades of Gone With The Wind fame, but others, while substantial and sturdy, are more modest. What they have in common today is that your tour guide will, most likely, be an earnest and eloquent young post-grad woman who will be dismissive about the white folk who lived in the big house, but will have much to say the black folk who suffered under the tyranny of the master and mistress.

rive out of Charlotte a few miles and you can visit beautifully preserved plantation houses. Some have the imposing classical facades of Gone With The Wind fame, but others, while substantial and sturdy, are more modest. What they have in common today is that your tour guide will, most likely, be an earnest and eloquent young post-grad woman who will be dismissive about the white folk who lived in the big house, but will have much to say the black folk who suffered under the tyranny of the master and mistress.

By contrast, a day’s drive south will find you in Charleston, South Carolina. Charleston is energetically preserved in architectural aspic, and if you are seeking people to share penance with you for the misdeeds of the Confederate States, you may struggle. In contrast to the spacious and well-funded Levine Museum in Charlotte, one of Charleston’s big draws is The Confederate Museum. Housed in an elevated brick copy of a Greek temple, it is administered by the Charleston Chapter of The United Daughters of The Confederacy. Pay your entrance fee and you will shuffle past a series of displays that would be the despair of any thoroughly modern museum curator. You definitely mustn’t touch anything, there are no flashing lights, dioramas, or interactive immersions into The Slave Experience. What you do have is a fascinating and random collection of documents, uniforms, weapons and portraits of extravagantly moustached soldiers, all proudly wearing the grey or butternut of the Confederate armies. The ladies who take your dollars for admission all look as if they have just returned from taking tea with Robert E Lee and his family.

By contrast, a day’s drive south will find you in Charleston, South Carolina. Charleston is energetically preserved in architectural aspic, and if you are seeking people to share penance with you for the misdeeds of the Confederate States, you may struggle. In contrast to the spacious and well-funded Levine Museum in Charlotte, one of Charleston’s big draws is The Confederate Museum. Housed in an elevated brick copy of a Greek temple, it is administered by the Charleston Chapter of The United Daughters of The Confederacy. Pay your entrance fee and you will shuffle past a series of displays that would be the despair of any thoroughly modern museum curator. You definitely mustn’t touch anything, there are no flashing lights, dioramas, or interactive immersions into The Slave Experience. What you do have is a fascinating and random collection of documents, uniforms, weapons and portraits of extravagantly moustached soldiers, all proudly wearing the grey or butternut of the Confederate armies. The ladies who take your dollars for admission all look as if they have just returned from taking tea with Robert E Lee and his family. Six hundred words in and what, I can hear you say, has this to do with crime fiction? In part two, I will look at crime writing – in particular the work of James Lee Burke and Greg Iles (but with many other references) – and how it deals with the very real and present physical, political and social peculiarities of the South. A memorable quote to round off this introduction is taken from William Faulkner’s Intruders In The Dust (1948). He refers to what became known as The High Point of The Confederacy – that moment on the third and fateful day of the Battle of Gettysburg, when Lee had victory within his grasp.

Six hundred words in and what, I can hear you say, has this to do with crime fiction? In part two, I will look at crime writing – in particular the work of James Lee Burke and Greg Iles (but with many other references) – and how it deals with the very real and present physical, political and social peculiarities of the South. A memorable quote to round off this introduction is taken from William Faulkner’s Intruders In The Dust (1948). He refers to what became known as The High Point of The Confederacy – that moment on the third and fateful day of the Battle of Gettysburg, when Lee had victory within his grasp.