The dark phantom of Jack The Ripper, whoever he (or she) might have been has haunted the world of crime fiction and True Crime writing for over 130 years. The catchy four-syllable nickname, probably cooked up by newspaper hacks in the first place, is never long absent from newspaper copy when serial killings have to be written about. Peter Sutcliffe, of course, became the Yorkshire cousin of the original killer, but headline writers in 1960s London plumbed new depths of bad taste and lack of originality when they covered a series of murders where the victims were all engaged in what is now primly known as “The Sex Industry”. Their dire effort? Why, Jack The Stripper, of course!

There are certainly similarities between the Hammersmith Murders and the Whitechapel killings. The victims were all women. They had all, at some point, sold their bodies for money. The locations, although not as tight together as those in 1888, were within a recognisable geographical area. There were ‘canonical’ victims; six in fact, as opposed to the generally accepted quintet during the luridly titled Autumn of Terror. There was subsequent talk of a well-known celebrity being involved. The case has inspired both True Crime reconstructions of the events, and novels based on the killings. Finally, of course, the killer was never found, despite subsequent theories claiming to finally identify the perpetrator. The Hammersmith victims were as follows:

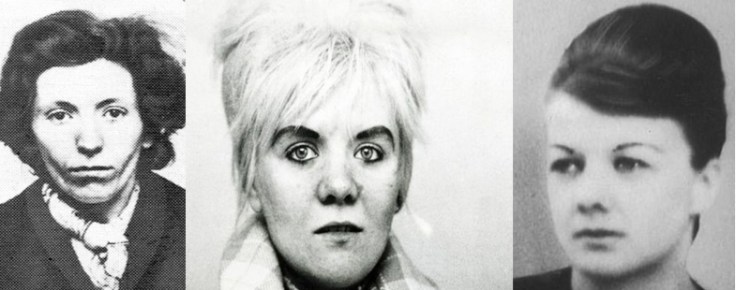

Hannah Tailford:Originally from Northumberland, Tailford was found dead on 2 February 1964 near Hammersmith Bridge. She had been strangled and several of her teeth were missing; her underwear had also been forced down her throat. She was age 30

Irene Lockwood: 26 year-old Lockwood was found dead on 8 April 1964 on the foreshore of the Thames, not far from where Tailford had been discovered; their two deaths were linked and police realized that a serial murderer was at large. Kenneth Archibald, a 57-year-old caretaker, confessed to this murder almost three weeks later, but his confession was dismissed due to inconsistencies in his version of events, and because of the discovery of a third victim.

Helen Barthelemy: Barthelemy, originally from Blackpool, was found dead on 24 April 1964 in an alleyway in Brentford. Barthelemy’s death gave investigators their first solid piece of evidence in the case: flecks of paint used in motor-car manufactories. Police felt that the paint had probably come from the killer’s workplace; they therefore focused on tracing it to a business nearby. Barthelemy was 22.

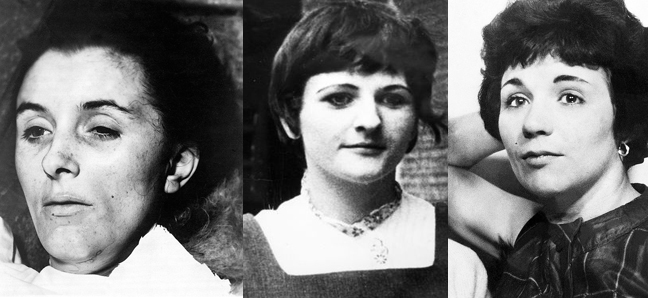

Mary Flemming: Flemming’s body was found on 14 July 1964 in a dead-end street in Chiswick. Once again, paint spots were found on the body; many neighbours had also heard a car reversing down the street just before the body was discovered. Mary Flemming was 30 years old.

Frances Brown: 21 year-old Brown was last seen alive on 23 October 1964 by her friend, fellow prostitute Kim Taylor, before her body was found in a car park in Kensington a month later on 25 November. Taylor, who had been with Brown when she was picked up by the man believed to be her killer, was able to provide police with an identikit picture and a description of the man’s car, thought to be either a Ford Zephyr or a Ford Zodiac.

Bridget O’Hara: O’Hara, also known as “Bridie”, was found dead on 16 February 1965 near a storage shed behind the Heron Trading Estate. She had been missing since 11 January. Once again, O’Hara’s body turned up flecks of industrial paint which, incredibly, were traced to a covered transformer just yards from where she had been discovered. Her body also showed signs of having been stored in a warm environment. Bridget O’Hara was 28 years old.

BOOKS ON THE CASE

Goodbye Piccadilly, Farewell Leicester Square (Anthony LeBern, 1966) is very loosely based on the Hammersmith Murders, and was later filmed as Frenzy (with many changes) by Alfred Hitchcock in 1972. The book title comes, of course, from the celebrated song It’s A Long Way To Tipperary.

Goodbye Piccadilly, Farewell Leicester Square (Anthony LeBern, 1966) is very loosely based on the Hammersmith Murders, and was later filmed as Frenzy (with many changes) by Alfred Hitchcock in 1972. The book title comes, of course, from the celebrated song It’s A Long Way To Tipperary.

Jack of Jumps ( David Seabrook, 2006) is a dazzling mixture of fact, fiction, contemporary accounts of the 1960s, real characters, imaginary conversations and a certain amount of psychogeography after the manner of Iain Sinclair. Seabrook also features Freddie Mills, who died in his car, parked in a London alley, apparently from a self inflicted gunshot.

Bad Penny Blues (Cathi Unsworth, 2009) sticks much closer to the original events, and features several thinly disguised real-life celebrities of the time, including the artist Pauline Boty, David ‘Screaming Lord’ Sutch, Joe Meek, crooner Michael Holliday, and ex-boxer and TV personality Freddie Mills (pictured below). The connection to the crimes is provided by a young copper who is drawn into the circle of Notting Hill artists and bohemians while his day job is to try and find the killer.

Bad Penny Blues (Cathi Unsworth, 2009) sticks much closer to the original events, and features several thinly disguised real-life celebrities of the time, including the artist Pauline Boty, David ‘Screaming Lord’ Sutch, Joe Meek, crooner Michael Holliday, and ex-boxer and TV personality Freddie Mills (pictured below). The connection to the crimes is provided by a young copper who is drawn into the circle of Notting Hill artists and bohemians while his day job is to try and find the killer.

Nick Fennimore is a forensic psychologist, and a Professor at the University of Aberdeen. His past gives him a painful and heartfelt stake in the hunt for a serial killer, as his own wife and child were snatched. Both are now lost to him; wife Rachel, because her body was found shortly after the abduction., and daughter Suzie – well, she is just lost. Neither sight nor sound of her has been sensed in the intervening years, but Fennimore clutches at the straw of her still being alive, and he feverishly scans his own personal CCTV footage of the Paris streets and boulevards in the hope of catching a glimpse of her.

Nick Fennimore is a forensic psychologist, and a Professor at the University of Aberdeen. His past gives him a painful and heartfelt stake in the hunt for a serial killer, as his own wife and child were snatched. Both are now lost to him; wife Rachel, because her body was found shortly after the abduction., and daughter Suzie – well, she is just lost. Neither sight nor sound of her has been sensed in the intervening years, but Fennimore clutches at the straw of her still being alive, and he feverishly scans his own personal CCTV footage of the Paris streets and boulevards in the hope of catching a glimpse of her.