English author and screenwriter John Lawton has long been a favourite of those readers who like literary crime fiction, and his eight Frederick Troy novels have become classics. Set over a long time-frame from the early years of WW2 to the 1960s, the books feature many real-life figures or, as in A Little White Death (1998), characters based on real people, in this case the principals in the Profumo Affair. In Then We Take Berlin (2013) Lawton introduced a new character, an amoral chancer whose real surname – Holderness – has morphed into Wilderness. Joe Wilderness is a clever, corrupt and calculating individual whose contribution to WW2 was minimal, but his career trajectory has widened from being a Schieber (spiv, racketeer) in the chaos of post-war Berlin to being in the employ of the British Intelligence services.

He is no James Bond figure, however. His dark arts are practised in corners, and with as little overt violence as possible. Hammer To Fall begins with a flashback scene,establishing Joe’s credentials as someone who would have felt at home in the company of Harry Lime, but we move then to the 1960s, and Joe is in a spot of bother. He is thought to have mishandled one of those classic prisoner exchanges which are the staple of spy thrillers, and he is sent by his bosses to weather the storm as a cultural attaché in Finland. His ‘mission’ is to promote British culture by traveling around the frozen north promoting visiting artists, or showing British films. His accommodation is spartan, to say the least. In his apartment:

He is no James Bond figure, however. His dark arts are practised in corners, and with as little overt violence as possible. Hammer To Fall begins with a flashback scene,establishing Joe’s credentials as someone who would have felt at home in the company of Harry Lime, but we move then to the 1960s, and Joe is in a spot of bother. He is thought to have mishandled one of those classic prisoner exchanges which are the staple of spy thrillers, and he is sent by his bosses to weather the storm as a cultural attaché in Finland. His ‘mission’ is to promote British culture by traveling around the frozen north promoting visiting artists, or showing British films. His accommodation is spartan, to say the least. In his apartment:

“The dining table looked less likely to be the scene of a convivial meal than an autopsy.”

Some of the worthies sent to Finland to wave the British flag are not to Joe’s liking:

“For two days Wilderness drove the poet Prudence Latymer to readings. She was devoutly Christian – not an f-word passed her lips – and seemed dedicated to simple rhyming couplets celebrating dance, spring, renewal, the natural world and the smaller breeds of English and Scottish dog.It was though TS Eliot had never lived. By the third day Wilderness was considering shooting her.”

Before he left England, his wife Judy offered him these words of advice:

“If you want a grant to stage Twelfth Night in your local village hall in South Bumpstead, Hampshire, the Arts Council will likely as not tell you to fuck off …. So, if you want to visit Lapland, I reckon your best bet is to suggest putting on a nude ballet featuring the over-seventies, atonal score by Schoenberg, sets by Mark Rothko ….. Ken Russell can direct … all the easy accessible stuff …. and you’ll probably pick up a whopping great grant and an OBE as well.”

So far, so funny – and Lawton (right) is in full-on Evelyn Waugh mode as he sends up pretty much everything and anyone. The final act of farce in Finland is when Joe earns his keep by sending back to London, via the diplomatic bag, several plane loads of …. well, state secrets, as one of Joe’s Russian contacts explains:

So far, so funny – and Lawton (right) is in full-on Evelyn Waugh mode as he sends up pretty much everything and anyone. The final act of farce in Finland is when Joe earns his keep by sending back to London, via the diplomatic bag, several plane loads of …. well, state secrets, as one of Joe’s Russian contacts explains:

“The Soviet Union has run out of bog roll. The soft stuff you used to sell to us in Berlin is now as highly prized as fresh fruit or Scotch whisky. We wipe our arses on documents marked Classified, Secret and sometimes even Top Secret. and the damned stuff won’t flush. So once a week a surly corporal lights a bonfire of Soviet secrets and Russian shit.”

But, as in all good satires – like Waugh’s Sword of Honour trilogy, and Catch 22 – the laughter stops and things take a turn to the dark side. Joe’s Finnish idyll comes to an end, and he is sent to Prague to impersonate a tractor salesman. By now, this is 1968, and those of us who are longer in the tooth know what happened in Czechoslavakia in 1968. Prague has a new British Ambassador, and one very familiar to John Lawton fans, as it is none other than Frederick Troy. As the Russians lose patience with Alexander Dubček and the tanks roll in, Joe is caught up in a desperate gamble to save an old flame, a woman whose decency has, over the years, been a constant reproach to him:

“Nell Burkhardt was probably the most moral creature he’d ever met. Raised by thieves and whores back in London’s East End, he had come to regard honesty as aberrant. Nell had never stolen anything, never lied …led a blameless life, and steered a course through it with the unwavering compass of her selfless altruism.”

Hammer To Fall is a masterly novel, bitingly funny and heartbreaking by turns. I think A Lily Of The Field is Lawton’s masterpiece, but this runs it pretty damned close. It is published by Grove Press, and is out today, 2nd April 2020.

Guy Portman (left) introduced us to Dyson Devereux in Necropolis (2014). I gave it 5* when writing for another review site, and I’ll include a link to that at the end of this post. Dyson was Head of Burials and Cemeteries in a fictional Essex town, and a rather individual young man. He is narcissistic, punctilious, cultured and, outwardly polite and thoughtful, but with an anarchic mind and a terrible propensity for extreme violence. The book both horrified and fascinated me but made me laugh out loud. Dyson Devereux was a Home Counties version of Patrick Bateman and his antics allowed Portman to poke savage fun at all kinds of modern social idiocies.

Guy Portman (left) introduced us to Dyson Devereux in Necropolis (2014). I gave it 5* when writing for another review site, and I’ll include a link to that at the end of this post. Dyson was Head of Burials and Cemeteries in a fictional Essex town, and a rather individual young man. He is narcissistic, punctilious, cultured and, outwardly polite and thoughtful, but with an anarchic mind and a terrible propensity for extreme violence. The book both horrified and fascinated me but made me laugh out loud. Dyson Devereux was a Home Counties version of Patrick Bateman and his antics allowed Portman to poke savage fun at all kinds of modern social idiocies. When he finally has his day in court, Dyson scorns the efforts of his lack-lustre lawyer and relies on his own charm and nobility of bearing to convince the court that he is an innocent man. He escapes the clinging arms of Alegra and returns to England without delay, anxious to be reunited with something from which separation has become a cruel burden. A loving family? A childhood sweetheart? The clear skies and careless rapture of an English summer day? No. A tin box containing several memento mori of his previous victims. Little oddments that he can sniff, fondle and treasure. Little bits of people who have had the temerity to upset him, and have paid the price.

When he finally has his day in court, Dyson scorns the efforts of his lack-lustre lawyer and relies on his own charm and nobility of bearing to convince the court that he is an innocent man. He escapes the clinging arms of Alegra and returns to England without delay, anxious to be reunited with something from which separation has become a cruel burden. A loving family? A childhood sweetheart? The clear skies and careless rapture of an English summer day? No. A tin box containing several memento mori of his previous victims. Little oddments that he can sniff, fondle and treasure. Little bits of people who have had the temerity to upset him, and have paid the price.

I must explain the apparent digression before you lose interest. Use your imagination. Conjure up a dreadful genetic experiment which breeds a being who, especially in his diarist’s style of first person narrative, shows very Pooteresque tendencies. But – and it is a ‘but’ the size of a third world country – the mad scientist has added Norman Bates and Hannibal Lecter into the mixing bowl, and then seasoned it with an eye-watering pinch of Patrick Bateman. What do you get? You get Dyson Devereux, Head of Cemeteries and Burials with Paleham Council.

I must explain the apparent digression before you lose interest. Use your imagination. Conjure up a dreadful genetic experiment which breeds a being who, especially in his diarist’s style of first person narrative, shows very Pooteresque tendencies. But – and it is a ‘but’ the size of a third world country – the mad scientist has added Norman Bates and Hannibal Lecter into the mixing bowl, and then seasoned it with an eye-watering pinch of Patrick Bateman. What do you get? You get Dyson Devereux, Head of Cemeteries and Burials with Paleham Council. The trip to Italy temporarily removes Dyson from the cross-hairs of the local police, and also the relatives of the late lamented Jeremiah, who are out for vengeance. What follows is brilliantly inventive, murderous and breathtakingly funny. Guy Portman doesn’t reveal too much about himself, even on

The trip to Italy temporarily removes Dyson from the cross-hairs of the local police, and also the relatives of the late lamented Jeremiah, who are out for vengeance. What follows is brilliantly inventive, murderous and breathtakingly funny. Guy Portman doesn’t reveal too much about himself, even on

Necropolis has a surreal plot involving, amongst other characters, an African drug dealer, a fugitive from the genocide of the 1990s Balkan wars – now working as a gravedigger – and a sadly deceased local resident for whom the undertakers have abandoned any pretence of good taste:

Necropolis has a surreal plot involving, amongst other characters, an African drug dealer, a fugitive from the genocide of the 1990s Balkan wars – now working as a gravedigger – and a sadly deceased local resident for whom the undertakers have abandoned any pretence of good taste: After a pause of three years, Dyson Devereux returns in Sepultura, to be published on 11th January. I have yet to get my hands on a copy, but it seems that Dyson has both a new job and a new son, but his cold rage and venomous disgust at his work colleagues and the world in general appears not to have abated one little bit. I can only guarantee that there will be death, cruelty, abrasive satire – and brilliant writing.

After a pause of three years, Dyson Devereux returns in Sepultura, to be published on 11th January. I have yet to get my hands on a copy, but it seems that Dyson has both a new job and a new son, but his cold rage and venomous disgust at his work colleagues and the world in general appears not to have abated one little bit. I can only guarantee that there will be death, cruelty, abrasive satire – and brilliant writing.

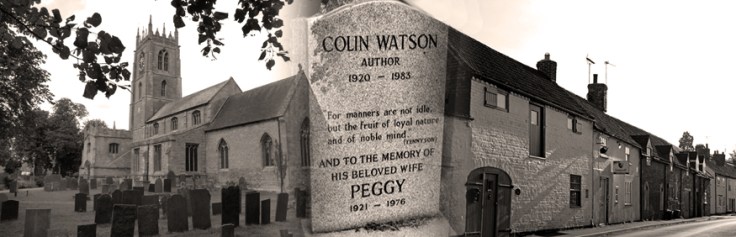

Coffin Scarcely Used – the first of The Flaxborough Chronicles – begins with the owner of the local newspaper dead in his carpet slippers, beneath an electricity pylon, on a winter’s night. Throw into the mix an over-sexed undertaker, a credulous housekeeper, the strangely shaped burns on the hands of the deceased, a chief constable who cannot believe that any of his golf chums could be up to no good, and a coffin containing only ballast, and we have a mystery which might be a Golden Age classic, were it not for the fact that Watson was, at heart, a satirist, and a writer who left no balloon of self importance unpricked.

Coffin Scarcely Used – the first of The Flaxborough Chronicles – begins with the owner of the local newspaper dead in his carpet slippers, beneath an electricity pylon, on a winter’s night. Throw into the mix an over-sexed undertaker, a credulous housekeeper, the strangely shaped burns on the hands of the deceased, a chief constable who cannot believe that any of his golf chums could be up to no good, and a coffin containing only ballast, and we have a mystery which might be a Golden Age classic, were it not for the fact that Watson was, at heart, a satirist, and a writer who left no balloon of self importance unpricked. In addition to such delightful titles as Broomsticks Over Flaxborough and Six Nuns And A Shotgun (in which Flaxborough is visited by a New York hitman) Watson also wrote an account of the English crime novel in its social context. In Snobbery With Violence (1971), he sought to explore the attitudes that are reflected in the detective story and the thriller. Readers expecting to find Watson reflecting warmly on his contemporaries and predecessors will be disappointed. The general tone of the book is almost universally waspish and, on some occasions, downright scathing.

In addition to such delightful titles as Broomsticks Over Flaxborough and Six Nuns And A Shotgun (in which Flaxborough is visited by a New York hitman) Watson also wrote an account of the English crime novel in its social context. In Snobbery With Violence (1971), he sought to explore the attitudes that are reflected in the detective story and the thriller. Readers expecting to find Watson reflecting warmly on his contemporaries and predecessors will be disappointed. The general tone of the book is almost universally waspish and, on some occasions, downright scathing.

In the end, it seems that Watson had supped full of crime fiction writing. Iain Sinclair sought him out in his later years at Folkingham, and wrote

In the end, it seems that Watson had supped full of crime fiction writing. Iain Sinclair sought him out in his later years at Folkingham, and wrote

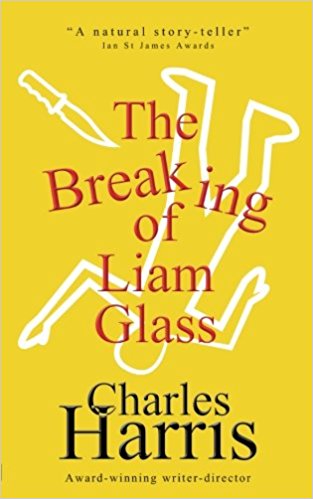

Charles Harris (right), a best-selling non-fiction author and writer-director for film and television sets in train a disastrous serious of mishaps, each of which stems from Kati’s ostensibly harmless error. Too exhausted from her daily grind making sure that Every Little Helps at everyone’s favourite supermarket, she sends her hapless son, Liam, off to the cashpoint, armed with her debit card and its vital PIN. Sadly, Liam never makes it home with the cash, the pizza guy remains unpaid, and Kati Glass is pitched into a nightmare.

Charles Harris (right), a best-selling non-fiction author and writer-director for film and television sets in train a disastrous serious of mishaps, each of which stems from Kati’s ostensibly harmless error. Too exhausted from her daily grind making sure that Every Little Helps at everyone’s favourite supermarket, she sends her hapless son, Liam, off to the cashpoint, armed with her debit card and its vital PIN. Sadly, Liam never makes it home with the cash, the pizza guy remains unpaid, and Kati Glass is pitched into a nightmare. Trying to find out who stabbed Liam Glass is Detective Constable Andy Rackham. He is a walking tick-box of all the difficulties faced by an ambitious copper trying to please his bosses while being a supportive husband and father. The third member of this unholy trinity is Jamila Hasan, an earnest politician of Bengali origin who senses that the attack might be just the campaign platform she needs to ensure that she is re-elected. But what if Liam’s attackers are from her own community? Sadly, in her efforts to gain credibility on the street, Jamila has been duped.

Trying to find out who stabbed Liam Glass is Detective Constable Andy Rackham. He is a walking tick-box of all the difficulties faced by an ambitious copper trying to please his bosses while being a supportive husband and father. The third member of this unholy trinity is Jamila Hasan, an earnest politician of Bengali origin who senses that the attack might be just the campaign platform she needs to ensure that she is re-elected. But what if Liam’s attackers are from her own community? Sadly, in her efforts to gain credibility on the street, Jamila has been duped.