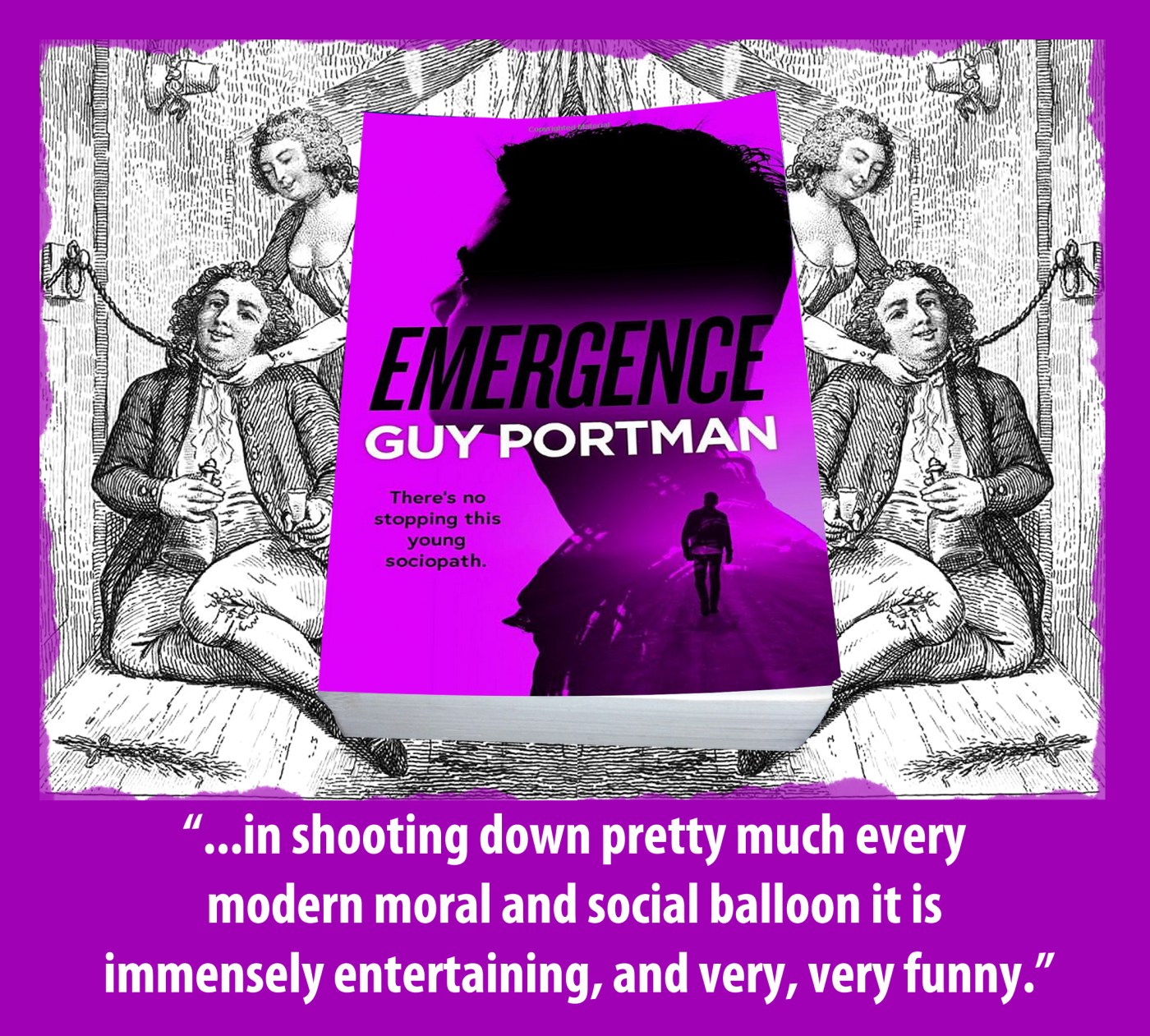

We rejoin our not-so-friendly neighbourhood sociopath Dyson Devereux in a London pub, where he is celebrating the end of his university exams with fellow undergraduates. He is miles away in his head, however:

“I left Tollington nearly eight years ago and have only been back twice. Aunt didn’t want me there after I pushed her daughter, Beatrice, off a cliff. It was considered to be an accident, but Aunt was suspicious. In my mind’s eye, I see Beatrice plummeting into the mist. This is my favorite memory.

“Ha, haha.”

Dyson needs to get a job, but before that rather tedious necessity, there are three more names on his to-kill list, and they are all in the Dorset town of Tollington. Top Trumps is the lecherous Dr Trenton who, years earlier had seduced Mrs Devereaux (while her husband was dying of AIDS) and filled her so full of tranquilisers that she lapsed into a fatal coma. Two elderly twins – Virulent Veronica and Conniving Clementine – who run a tea-shop must also die because of their persistent taunting of the younger Dyson, publicly stigmatising him for his father’s alleged sins. After eventually passing his driving test, Dyson tours local used car yards for his first set of wheels. He has one main criterion. The car’s boot must be wide enough to accommodate the Samurai sword – honed to razor sharpness – which hangs on he bedroom wall of his student digs.

Dyson is devastated to learn that one of the malignant twins has thwarted his vengeance by dying of old age. Undaunted, he executes her sister and returns to London where, after befriending the daughter of an Indian billionaire. he is invited to an the launch party of an art exhibition by a young man called Sebastian

‘A grim-faced waiter, wearing a bright green tail coat, materializes next to me.He is holding out a plate.

“Tuna balls with cream cheese and red onion.”

I help myself to one. It tastes piquant. The exhibition’s art is being put to shame by the seafood Hors d’Oevre. Sebastian is devoid of artistic talent. However, he has one thing going for him. His German mother is an heiress to a pharmaceutical fortune.’

After a few false starts, Dyson finally puts the Samurai sword to use in the manner for which it was designed, and his trilogy of vengeance seems to be over. Despite some interest from the police, he has covered his tracks so carefully that the two most recent crimes cannot be pinned on him, and he begins his working career in the less-than-exotic offices of a London borough council in their Green Spaces Department. This segues fairly neatly into the first book – in publishing chronology – of the series, Necropolis, which I reviewed in 2014 (click here to read)

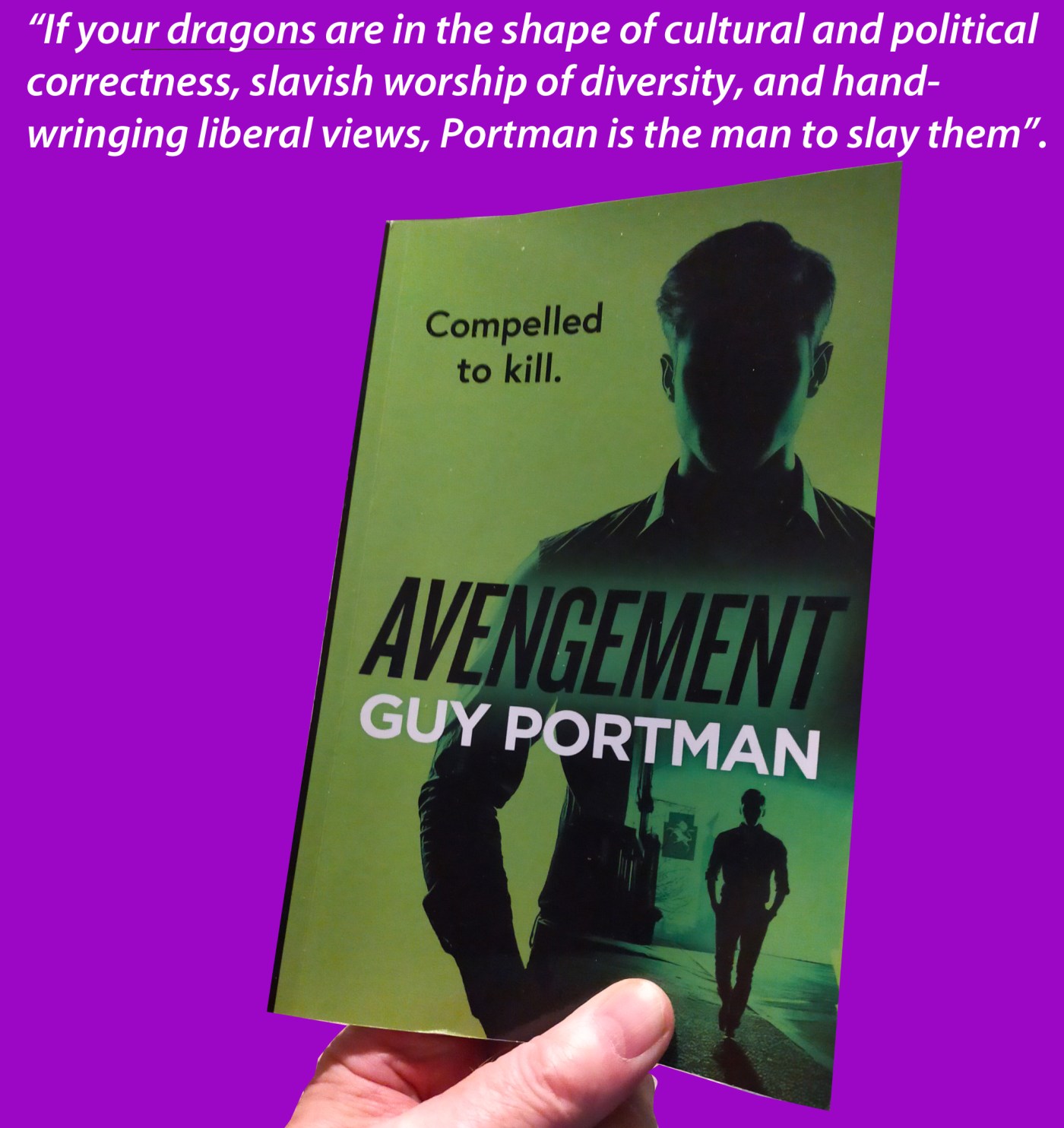

Satire in Britain is, in my view, in a fairly bad way at the moment. Like comedy, it seems to have just been absorbed into the prevailing metropolitan liberal mindset, which only considers the political right as a legitimate target. Private Eye is a shadow of its former self, and I gave up on HIGNFY years ago. Rare is the journalist who challenges the prevailing Islingtonian doctrines through comedy, Rod Liddle being perhaps one exception. I can’t think of anyone who writes quite like Guy Portman. Jonathan Meades is similarly trenchant and iconoclastic, but even his last novel had to be crowd-funded, as no publisher would touch it. If your dragons are in the shape of cultural and political correctness, slavish worship of diversity, and hand-wringing liberal views, Portman is your St George. Avengement is available now.

On his trail is a grotesque cartoon of a copper – DCI Dave Hicks. He lives at home with his dear old mum, has a prodigious appetite for her home-cooked food, is something of a media whore (he does love his press conferences) and has a shaky grasp of English usage, mangling idioms like a 1980s version of Mrs Malaprop.

On his trail is a grotesque cartoon of a copper – DCI Dave Hicks. He lives at home with his dear old mum, has a prodigious appetite for her home-cooked food, is something of a media whore (he does love his press conferences) and has a shaky grasp of English usage, mangling idioms like a 1980s version of Mrs Malaprop. “A fuchsia -pink shirt with outsize wing collar, over-tight lime green denim jeans, a brand new squeaky-clean leather jacket and, just for good measure, a black beret with white trim.”

“A fuchsia -pink shirt with outsize wing collar, over-tight lime green denim jeans, a brand new squeaky-clean leather jacket and, just for good measure, a black beret with white trim.”

I have spent longer on the biographical details of John Betjeman because, in what was his longest and most profound poem, Summoned By Bells (1960), he writes his autobiography in blank verse.

I have spent longer on the biographical details of John Betjeman because, in what was his longest and most profound poem, Summoned By Bells (1960), he writes his autobiography in blank verse.

So what are we to make of Betjeman’s poetry today, the age of cancel culture, triggered university graduates, and the most virulent class war that I can remember in my seventy-odd years of being sentient? He has been described – by lesser writers – as mediocre. His prevailing themes included the foibles and rituals of the English middle class, churches, railways, Victorian buildings and London. Hardly the stuff to bring him to the cutting edge of the literary razor in 2022, admittedly. But his detractors – or those who see him as an anachronistic bumbler, mugging it up for TV cameras and radio microphones – miss the point, big time. Time and space forced me to ignore the sheer joy found in his description of railway stations, gymkhanas, Edwardian suburbs and churches and look at his compassion. In

So what are we to make of Betjeman’s poetry today, the age of cancel culture, triggered university graduates, and the most virulent class war that I can remember in my seventy-odd years of being sentient? He has been described – by lesser writers – as mediocre. His prevailing themes included the foibles and rituals of the English middle class, churches, railways, Victorian buildings and London. Hardly the stuff to bring him to the cutting edge of the literary razor in 2022, admittedly. But his detractors – or those who see him as an anachronistic bumbler, mugging it up for TV cameras and radio microphones – miss the point, big time. Time and space forced me to ignore the sheer joy found in his description of railway stations, gymkhanas, Edwardian suburbs and churches and look at his compassion. In

TO ALL THE LIVING . . . Between the covers

This is the latest in the series of excellent reprints from the Imperial War Museum. They have ‘rediscovered’ novels written about WW2, mostly by people who experienced the conflict either home or away. Previous books can be referenced by clicking this link.

We are, then, immediately into the dangerous territory of judging creative artists because of their politics, which never ends well, whether it involves the Nazis ‘cancelling’ Mahler because he was Jewish or more recent critics shying away from Wagner because he was anti-semitic and, allegedly, admired by senior figures in the Third Reich. The longer debate is for another time and another place, but it is an inescapable fact that many great creative people, if not downright bastards, were deeply unpleasant and misguided. To name but a few, I don’t think I would have wanted to list Caravaggio, Paul Gauguin, Evelyn Waugh, Eric Gill or Patricia Highsmith among my best friends, but I would be mortified not to be able to experience the art they made.

So, could Monica Felton write a good story, away from hymning the praises of KIm Il Sung and his murderous regime? To All The Living (1945) is a lengthy account of life in a British munitions factory during WW2, and is principally centred around Griselda Green, a well educated young woman who has decided to do her bit for the country. To quickly answer my own question, the answer is a simple, “Yes, she could.”

Another question could be, “Does she preach?“ That, to my mind, is the unforgivable sin of any novelist with strong political convictions. Writers such as Dickens and Hardy had an agenda, certainly, but they subtly inserted this between the lines of great story-telling. Felton is no Dickens or Hardy, but she casts a wry glance at the preposterous bureaucracy that ran through the British war effort like the veins in blue cheese. She highlights the endless paperwork, the countless minions who supervised the completion of the bumf, and the men and women – usually elevated from being section heads in the equivalent of a provincial department store – who ruled over the whole thing in a ruthlessly delineated hierarchy.

Amid the satire and exaggerated portraits of provincial ‘jobsworths’ there are darker moments, such as the descriptions of rampant misogyny, genuine poverty among the working classes, and the very real chance that the women who filled shells and crafted munitions – day in, day out – were in danger of being poisoned by the substances they handled. The determination of the factory managers to keep these problems hidden is chillingly described. These were rotten times for many people in Britain, but if Monica Felton believed that things were being done differently in North Korea or the USSR, then I am afraid she was sadly deluded.

The social observation and political polemic is shot through with several touches or romance, some tragedy, and the mystery of who Griselda Green really is. What is a poised, educated and well-spoken young woman doing among the down-to-earth working class girls filling shells and priming fuzes?

My only major criticism of this book is that it’s perhaps 100 pages too long. The many acerbic, perceptive and quotable passages – mostly Felton’s views on the more nonsensical aspects of British society – tend to fizz around like shooting stars in an otherwise dull grey sky.

Is it worth reading? Yes, of course, but you must be prepared for many pages of Ms Felton being on communist party message interspersed with passages of genuinely fine writing. To All The Living is published by the Imperial War Museum, and is out now.