James Barlow was a Birmingham-born novelist who served as an air gunner with the RAF in WWII. Invalided out of service when he contracted tuberculosis, he faced a long convalescence. He began writing at this time, and after he worked in his native city as, of all things, a water rates inspector, he made the decision to write for a living. His first novel, The Protagonists, was published in 1956, but made little impact. It wasn’t until Term of Trial (1961) that he began to make a decent living from writing, and then more because film director Peter Glenville saw the cinematic potential in the story of an alcoholic school teacher whose career is threatened when he is accused of improper behaviour with a female pupil. The subsequent film had a star-studded cast including Sir Laurence Olivier, Simone Signoret, Sarah Miles, Terence Stamp, Hugh Griffith, Dudley Foster, Thora Hird and Alan Cuthbertson.

James Barlow was a Birmingham-born novelist who served as an air gunner with the RAF in WWII. Invalided out of service when he contracted tuberculosis, he faced a long convalescence. He began writing at this time, and after he worked in his native city as, of all things, a water rates inspector, he made the decision to write for a living. His first novel, The Protagonists, was published in 1956, but made little impact. It wasn’t until Term of Trial (1961) that he began to make a decent living from writing, and then more because film director Peter Glenville saw the cinematic potential in the story of an alcoholic school teacher whose career is threatened when he is accused of improper behaviour with a female pupil. The subsequent film had a star-studded cast including Sir Laurence Olivier, Simone Signoret, Sarah Miles, Terence Stamp, Hugh Griffith, Dudley Foster, Thora Hird and Alan Cuthbertson.

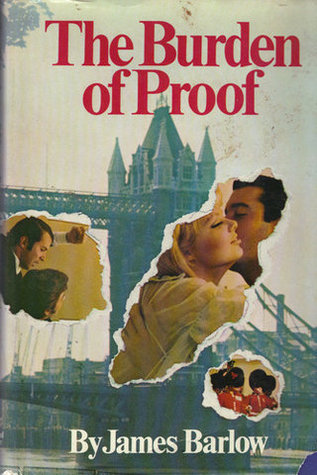

Term of Trial was a powerful and controversial film, but clearly had nothing to do with crime fiction. Barlow’s 1968 novel The Burden of Proof was another matter. By the time it was published, the Kray twins’ days as despotic rulers of London’s gangland were numbered. They were arrested on 8th May in that year and the rest, as they say, is history. The Burden of Proof is centred on a Ronnie Kray-style gangster, Vic Dakin. Dakin is psychotic homosexual, devoted equally to his dear old mum and a succession of pliant boyfriends, while finding time to be at the hub of a violent criminal network.

Term of Trial was a powerful and controversial film, but clearly had nothing to do with crime fiction. Barlow’s 1968 novel The Burden of Proof was another matter. By the time it was published, the Kray twins’ days as despotic rulers of London’s gangland were numbered. They were arrested on 8th May in that year and the rest, as they say, is history. The Burden of Proof is centred on a Ronnie Kray-style gangster, Vic Dakin. Dakin is psychotic homosexual, devoted equally to his dear old mum and a succession of pliant boyfriends, while finding time to be at the hub of a violent criminal network.

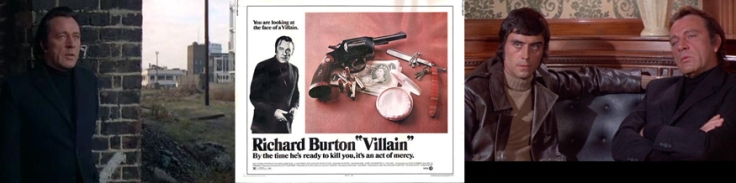

The cast of the subsequent film version of The Burden of Proof was similarly stellar to that of Term of Trial. Villain (1971) starred none other than Richard Burton, Ian McShane, Nigel Davenport, Joss Ackland, Donald Sinden and T.P, McKenna.

Barlow seems to have been a fairly misanthropic fellow who raged at what he believed was a gathering darkness afflicting an England that he once loved. A year after The Burden of Proof was published he decided he’d had enough, and decided to relocate to a place to which many Englishmen of a previous generation were sent as a punishment – Van Diemen’s Land, latterly rebranded as Tasmania. Barlow’s departure was accompanied by a fanfare of his own devising, a rancorous demolition job on what he saw as a corrupted and increasingly shallow country – Goodbye England (1969)

Much of Barlow’s intense disgust at what was happening around him spills out onto the pages of The Burden of Proof. The crime plot centres on Dakin’s plan to pull off a lucrative wages heist, but this almost becomes secondary to Barlow’s polemic about his homeland being reduced to what he saw as an obscene freak show where morality and integrity were turned on their heads in favour of a mindless and debased popular culture. Re-reading the novel exactly half a century after it was published, I am astonished by how contemporary his words sound. They could be put in the mouths of many modern alt-right commentators. Given access to today’s social media he would rage like an Old Testament prophet and, just like his modern counterparts, he would enrage and delight in equal measure.

Barlow on Speakers’ Corner and the how the statuary of London acts as a metaphor:

“The small indifferent crowds hung around the rostrums on Sundays, laughing at the remnants of free speech. The pigeons excreted as they stood on the heads of statues of forgotten men of a time despised now by the liberals who knew better …”

1960s London is portrayed in the bleakest of descriptions:

“London was tired, seedy, cunning, ugly, here and there beautiful. In 1914 it had been at its most powerful; in 1940 at its most heroic. Now, in the 1960s, it was impotent and had the principles and self-importance of an old queer.”

As I read Barlow’s cri de cœur about what he clearly saw as the triumph of the metropolitan elite, I might have been something by Rod Liddle in one of his recent rants in The Spectator or The Sunday Times;

“Nobody could do anything now without being accountable to the scorn of the liberal intellectuals in print or on television. England was too articulate at the top. Nobody, even in a Socialist liberal permissive society, had the slightest notion of the wishes of the people, out there beyond the great conversational shop of London.”

In the city which is portrayed as little more than a moral sewer, we have the vile Dakin and his criminal associates; we have an earnest and incorruptible copper, Bob Matthews who Barlow sets up – along with Bob’s mild-mannered and decent wife Mary – as the apotheosis of what England used to be before the plague took hold. We have Gerald Draycott, a dishonest and manipulative MP who flirts with the dangerous world of gambling clubs, casinos, girls-for-hire and drugs-for-sale, but still dreams of becoming a cabinet minister.

In the city which is portrayed as little more than a moral sewer, we have the vile Dakin and his criminal associates; we have an earnest and incorruptible copper, Bob Matthews who Barlow sets up – along with Bob’s mild-mannered and decent wife Mary – as the apotheosis of what England used to be before the plague took hold. We have Gerald Draycott, a dishonest and manipulative MP who flirts with the dangerous world of gambling clubs, casinos, girls-for-hire and drugs-for-sale, but still dreams of becoming a cabinet minister.

Back to the crime story. Dakin’s attempted wage-snatch, described in terrifying detail, does not go according to plan, but such is the depth, ferocity and intensity of the man’s evil, that there are casualties a-plenty beforte he gets his come-uppance. There is also a terrible incident, unconnected and not criminal by intent but more a result of negligence, which is described in horrific detail and left me dry-mouthed with a mixture of pity and shock. Of the people, volunteers, who help with the consequences of the disaster, Barlow says;

“They came when England and London needed them, and sank back into obscurity afterwards while the more important people postured before cameras with their guitars or explained the need to hate Rhodesians, or Arabs, or Israelis, or Americans…”

Nothing else I have read by Barlow comes close to The Burden of Proof in terms of its rage, its disgust and the sheer firepower of words when used by someone who believes he is on a mission. You may be appalled, you may be left thanking whoever you believe in that we live in more ‘enlightened’ times, but if you read this bitter and brilliant novel and don’t experience an emotional jolt then you may well be in a permanent vegetative state.

For a more recent slant on the real life connection between Ronnie Kray and powerful political figures in the 1960s, take a look at Simon Michael’s novel Corrupted.

When we next meet Charles it is 1964, and much has changed. The streets of the old East End, having been substantially rearranged by Hitler’s bombs, have been redeveloped. More significantly, the Jewish people have largely moved on. Many families have prospered and they have moved out to the comfortable suburbs. Charles Horowitz has also prospered, after a fashion. His chosen career is Law, and in order to rise through the ranks of the socially and ethnically tightly knit Inns of Court, he has abandoned Horowitz and reinvented himself as Charles Holborne.

When we next meet Charles it is 1964, and much has changed. The streets of the old East End, having been substantially rearranged by Hitler’s bombs, have been redeveloped. More significantly, the Jewish people have largely moved on. Many families have prospered and they have moved out to the comfortable suburbs. Charles Horowitz has also prospered, after a fashion. His chosen career is Law, and in order to rise through the ranks of the socially and ethnically tightly knit Inns of Court, he has abandoned Horowitz and reinvented himself as Charles Holborne. for those who want to complete the picture, but with The Lighterman it is sufficient to say that Charles has made a very undesirable enemy. It is probably merely an exercise in semantics to distinguish between the equally awful twin sons of Charles David Kray and Violet Annie Lee, but most casual observers agree that Ronnie was the worst of two evils. The homosexual, paranoid and pathologically violent gangster has a list of people who have upset him. The first name on that list is none other than Charles Holborne aka Horowitz, and the brutal East End hoodlum is determined that Charles must be done away with.

for those who want to complete the picture, but with The Lighterman it is sufficient to say that Charles has made a very undesirable enemy. It is probably merely an exercise in semantics to distinguish between the equally awful twin sons of Charles David Kray and Violet Annie Lee, but most casual observers agree that Ronnie was the worst of two evils. The homosexual, paranoid and pathologically violent gangster has a list of people who have upset him. The first name on that list is none other than Charles Holborne aka Horowitz, and the brutal East End hoodlum is determined that Charles must be done away with. Simon Michael (left) combines an encyclopaedic knowledge of London, with an insider’s grasp of courtroom proceedings. I cannot say if it was the author’s intention – only he can concur or disagree – but his writing left me with a profound sense of sadness over what London’s riverside and its East End once were – and what they have become. This is a beautifully written novel which succeeds on three different levels. Firstly, it is a superb recreation of a London which is just a lifetime away, but may as well be the Egypt of the pharaohs, such is its distance from us. Secondly, it is a tense and authentic legal thriller, with all the nuances and delicate sensibilities of the British legal system pushed into the spotlight. Thirdly – and perhaps most importantly – we meet characters who are totally convincing, speak in a manner which sounds authentic, and have all the qualities and flaws which we recognise in people of our own acquaintance. The Lighterman is published by Urbane Publications and is

Simon Michael (left) combines an encyclopaedic knowledge of London, with an insider’s grasp of courtroom proceedings. I cannot say if it was the author’s intention – only he can concur or disagree – but his writing left me with a profound sense of sadness over what London’s riverside and its East End once were – and what they have become. This is a beautifully written novel which succeeds on three different levels. Firstly, it is a superb recreation of a London which is just a lifetime away, but may as well be the Egypt of the pharaohs, such is its distance from us. Secondly, it is a tense and authentic legal thriller, with all the nuances and delicate sensibilities of the British legal system pushed into the spotlight. Thirdly – and perhaps most importantly – we meet characters who are totally convincing, speak in a manner which sounds authentic, and have all the qualities and flaws which we recognise in people of our own acquaintance. The Lighterman is published by Urbane Publications and is

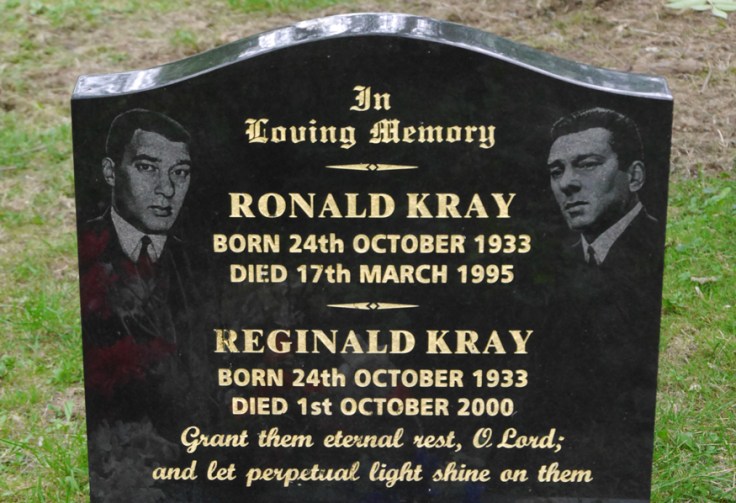

REGGIE AND RONNIE KRAY have been the subject of almost as many books, documentaries and dramas as their 19th century near-neighbour Jack the Ripper. The East End that he – whoever he was – knew has changed almost beyond recognition. The Bethnal Green of the Krays is heading in the same direction, but a few landmarks remain unscathed. They were born out in Hoxton in October 1933, Reggie being the older by ten minutes. The family moved into Bethnal Green in 1938, and they lived at 178 Vallance Road. That house no longer stands, modern houses having been built on the site (left)

REGGIE AND RONNIE KRAY have been the subject of almost as many books, documentaries and dramas as their 19th century near-neighbour Jack the Ripper. The East End that he – whoever he was – knew has changed almost beyond recognition. The Bethnal Green of the Krays is heading in the same direction, but a few landmarks remain unscathed. They were born out in Hoxton in October 1933, Reggie being the older by ten minutes. The family moved into Bethnal Green in 1938, and they lived at 178 Vallance Road. That house no longer stands, modern houses having been built on the site (left)

George Cornell (right) had known the twins from childhood. Their careers had developed more or less on similar lines, except that Cornell became the enforcer for the Richardsons. On 7th March 1966 there was a confused shoot-out at a club in Catford. Members of the Kray gang and the Richardsons gang were involved. At some point, George Cornell had been heard to refer to Ronnie Kray as a “fat poof.” That might seem unkind, but was not totally inaccurate. Ronnie was certainly plumper than his lean and hungry twin, and his liking for handsome boys was well known.

George Cornell (right) had known the twins from childhood. Their careers had developed more or less on similar lines, except that Cornell became the enforcer for the Richardsons. On 7th March 1966 there was a confused shoot-out at a club in Catford. Members of the Kray gang and the Richardsons gang were involved. At some point, George Cornell had been heard to refer to Ronnie Kray as a “fat poof.” That might seem unkind, but was not totally inaccurate. Ronnie was certainly plumper than his lean and hungry twin, and his liking for handsome boys was well known. On the evening of 9th March, Cornell and an associate were unwise enough to call in for a drink at a The Blind Beggar pub on Whitechapel Road, very much in Kray territory. Some thoughtful soul telephoned Ronnie Kray, who was drinking in a nearby pub, The Lion in Tapp Street (left). Ronnie, pausing only to collect a handgun made straight for the Blind Beggar, strode in, and shot George Cornell in the head at close range. His death was almost instantaneous. Needless to say, no-one else in the pub had seen anything. Pictured below are a post mortem photograph of Cornell, and the bloodstained floor of The Blind Beggar. Below that is the fatal pub, then and now.

On the evening of 9th March, Cornell and an associate were unwise enough to call in for a drink at a The Blind Beggar pub on Whitechapel Road, very much in Kray territory. Some thoughtful soul telephoned Ronnie Kray, who was drinking in a nearby pub, The Lion in Tapp Street (left). Ronnie, pausing only to collect a handgun made straight for the Blind Beggar, strode in, and shot George Cornell in the head at close range. His death was almost instantaneous. Needless to say, no-one else in the pub had seen anything. Pictured below are a post mortem photograph of Cornell, and the bloodstained floor of The Blind Beggar. Below that is the fatal pub, then and now.

Folklore has it that now that Ronnie had ‘done the big one’, there was pressure on Reggie to match his twin’s achievement. The chance was over a year in coming. Jack McVitie (right) was a drug addicted criminal enforcer who worked, on and off, for the Krays. His nickname ‘The Hat’ was because he was embarrassed about his thinning hair, and always wore a trademark trilby. McVitie had taken £500 from the Krays to kill someone, had botched the job, but kept the money. He had also, unwisely,been heard to bad-mouth the twins.

Folklore has it that now that Ronnie had ‘done the big one’, there was pressure on Reggie to match his twin’s achievement. The chance was over a year in coming. Jack McVitie (right) was a drug addicted criminal enforcer who worked, on and off, for the Krays. His nickname ‘The Hat’ was because he was embarrassed about his thinning hair, and always wore a trademark trilby. McVitie had taken £500 from the Krays to kill someone, had botched the job, but kept the money. He had also, unwisely,been heard to bad-mouth the twins. On the night of 29th October 1967, McVitie was lured to a basement flat in Evering Road, Stoke Newington,(left) on the pretext of a party. There, he was met by Reggie Kray and other members of the firm. Kray’s attempt to shoot McVitie misfired – literally – and instead, he stabbed McVitie repeatedly with a carving knife. McVitie’s body was never found, and the stories about his eventual resting place range from his being fed to the fishes of the Sussex coast to being buried incognito in a Gravesend cemetery.

On the night of 29th October 1967, McVitie was lured to a basement flat in Evering Road, Stoke Newington,(left) on the pretext of a party. There, he was met by Reggie Kray and other members of the firm. Kray’s attempt to shoot McVitie misfired – literally – and instead, he stabbed McVitie repeatedly with a carving knife. McVitie’s body was never found, and the stories about his eventual resting place range from his being fed to the fishes of the Sussex coast to being buried incognito in a Gravesend cemetery.