The first thing to say is that the title won’t make much sense if you just randomly saw it on a shelf, but pick it up and you will see it is the first part of a trilogy, the two following novels being Skins and Kills. We meet Arran Cunningham, a young Scot. He is a Metropolitan Police officer working in Hackney, East London. Not being a Londoner, I have no idea what Hackney is like these days. I suspect it may have become more gentrified than it was in the spring of 1988. What Cunningham sees when he is walking his beat is something of a warzone. There is a large black population, mostly of Jamaican origin, and the lid is only just holding its own on a pot of simmering racial tensions, turf wars between drug gangs and a general air of despair and degeneration.

The pivotal event in the novel is a mugging (for expensive trainers) that turns into rape. The victim is a black teenager called Nadia Carrick. The attackers are a trio of young white men, led by a boy nicknamed Spider. They are unemployed, drug addicted, and live in a squat. Nadia tries to conceal the attack from her father, Stanton, but eventually he learns the true extent of her nightmare, and he seeks retribution. Stanton Carrick is an accountant, but a rather special one. His sole employer is Eldine Campbell, ostensibly a club and café owner, but actually the main drugs boss in the borough, and someone who needs his obscene profits legitimised.

Carrick is also a great friend of Arran Cunningham, who learns what has happened to Nadia. Purely by luck he saw Spider and his two chums on the night of the incident, but was unaware at the time of what had happened. Rather than use his own men to avenge Nadia’s rape, Eldine Campbell has a rather interesting solution. He has what could be called a “special relationship’ with a group of police officers, led by Detective Chief Inspector Vince Girvan, and he assigns them the task of dealing with with the perpetrators.

Meanwhile, Girvan has taken a special interest in Arran Cunningham, and assigns him to plain clothes duties, the first of which is to be a part of the crew eliminating Spider and his cronies. In at the deep end, he is not involved with their abduction, but is brought in as the trio are executed in a particularly grisly – but some might say appropriate – fashion. There is problem, though, and it is a big one. He recognises Spider’s two accomplices, but the third man is just someone random, and totally innocent of anything involving Nadia.

The three bodies are disposed of in the traditional fashion via a scrapyard crushing machine, but Cunningham is in a corner. His dilemma is intensified when his immediate boss, DI Kat Skeldon, aware that there is a police force within a police force operating, enrols him to be ‘on the side of the angels.’ As if things couldn’t become more complex, Cunningham learns that Stanton Carrick is dying of cancer.

Durnie’s plot trajectory which, thus far, had seemed on a fairly steady arc, spins violently away from its course when he reveals a totally unexpected relationship between two of the principle players in this drama, and this forces Cunningham into drastic action.

Durnie’s plot trajectory which, thus far, had seemed on a fairly steady arc, spins violently away from its course when he reveals a totally unexpected relationship between two of the principle players in this drama, and this forces Cunningham into drastic action.

The author (left) was a long-serving officer in the Met, and so we can take it as read that his descriptions of their day-to-day procedures are authentic. In Arran Cunningham, he has created a perfectly credible anti-hero. I am not entirely sure that he is someone I would trust with my life, but I eagerly await the next instalment of his career. Hunts is published by Caprington Press and will be available on 8th January.

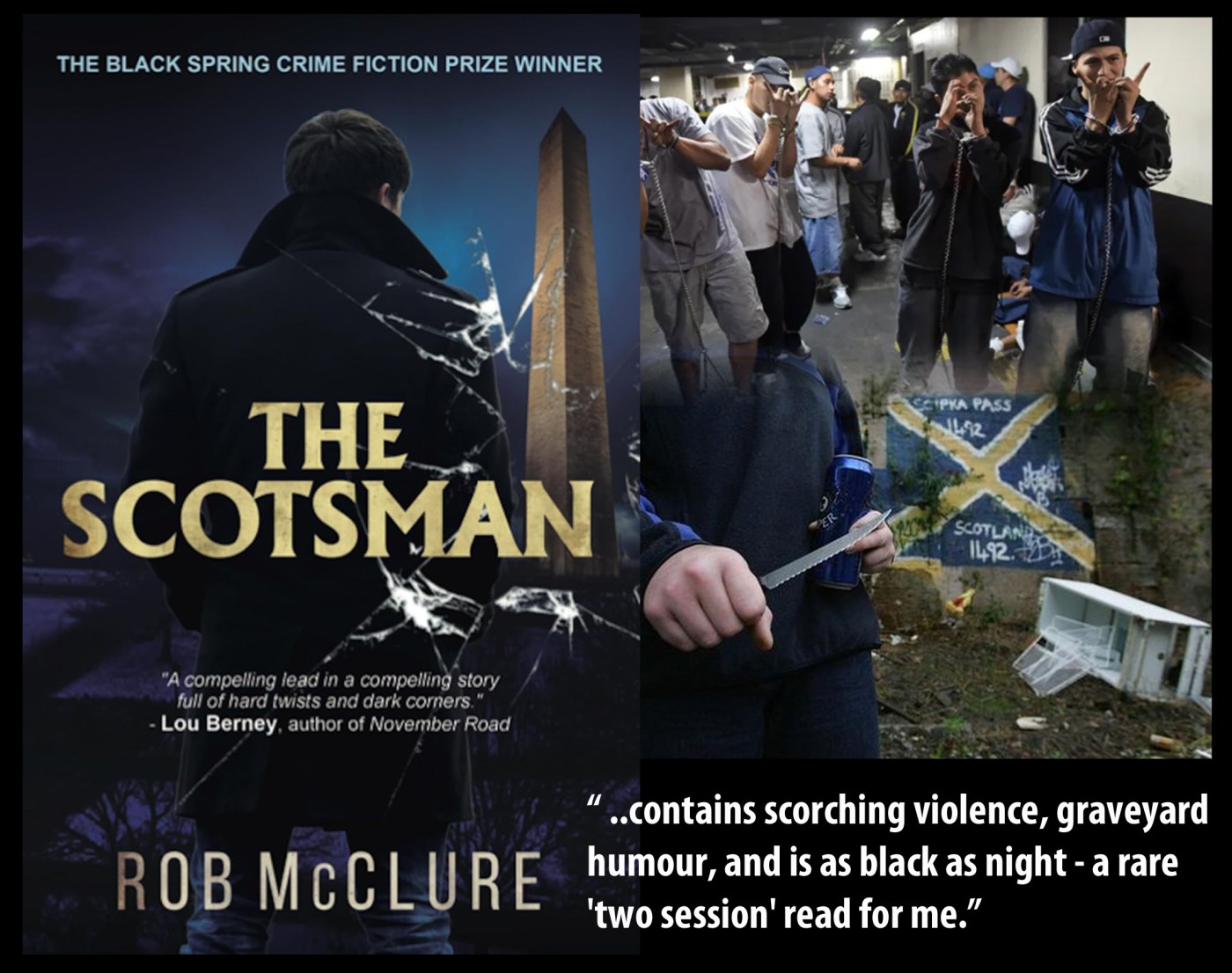

The trope of a police officer investigating a crime “off patch” or in an unfamiliar mileu is not new, especially in film. At its corniest, we had John Wayne in Brannigan (1975) as the Chicago cop sent to London to help extradite a criminal, and in Coogan’s Bluff (1968), Clint Eastwood’s Arizona policeman, complete with Stetson, is sent to New York on another extradition mission. Black Rain (1989) has Michael Douglas locking horns with the Yakuza in Japan, and who can forget Liam Neeson’s unkindness towards Parisian Albanians in Taken (2018), but apart from 9 Dragons (2009), where Michael Connolly’s Harry Bosch goes to war with the Triads in Hong Kong, I can’t recall many crime novels in the same vein. Rob McClure (left) balances this out with his debut novel, The Scotsman, which was edited by Luca Veste.

The trope of a police officer investigating a crime “off patch” or in an unfamiliar mileu is not new, especially in film. At its corniest, we had John Wayne in Brannigan (1975) as the Chicago cop sent to London to help extradite a criminal, and in Coogan’s Bluff (1968), Clint Eastwood’s Arizona policeman, complete with Stetson, is sent to New York on another extradition mission. Black Rain (1989) has Michael Douglas locking horns with the Yakuza in Japan, and who can forget Liam Neeson’s unkindness towards Parisian Albanians in Taken (2018), but apart from 9 Dragons (2009), where Michael Connolly’s Harry Bosch goes to war with the Triads in Hong Kong, I can’t recall many crime novels in the same vein. Rob McClure (left) balances this out with his debut novel, The Scotsman, which was edited by Luca Veste.

Brat Farrar is an ingenious invention. He is an orphan, and even his name is the result of administrative errors and poor spelling. He has been around the world trying to earn a living in such exotic locations as New Mexico, but has ended up in London, virtually penniless and becomes an easy mark for a chancer like Alec Loding. He is initially reluctant to take art in the scheme, but with Loding’s meticulous coaching – and his own uncanny resemblance to the late Patrick – he convinces the Ashbys that he is the real thing. But – and it is a very large ‘but’ – Brat senses that Simon Ashby has his doubts, and they soon reach a disturbing kind of equanimity. Each knows the truth about the other, but dare not say. The author’s solution to the conundrum is elegant, and the endgame is both gripping and has a sense of natural justice about it.

Brat Farrar is an ingenious invention. He is an orphan, and even his name is the result of administrative errors and poor spelling. He has been around the world trying to earn a living in such exotic locations as New Mexico, but has ended up in London, virtually penniless and becomes an easy mark for a chancer like Alec Loding. He is initially reluctant to take art in the scheme, but with Loding’s meticulous coaching – and his own uncanny resemblance to the late Patrick – he convinces the Ashbys that he is the real thing. But – and it is a very large ‘but’ – Brat senses that Simon Ashby has his doubts, and they soon reach a disturbing kind of equanimity. Each knows the truth about the other, but dare not say. The author’s solution to the conundrum is elegant, and the endgame is both gripping and has a sense of natural justice about it. Josephine Tey was one of the pseudonyms of Elizabeth MacKintosh (1896-1952) Her play, Richard of Bordeaux (written as Gordon Daviot) was celebrated in its day, and was produced by – and starred – John Gielgud. She never married, but a dear friend – perhaps an early romantic attachment – was killed on the Somme in 1916. She remained an enigma – even to friends who thought themselves close – throughout her life. Her funeral was reported thus:

Josephine Tey was one of the pseudonyms of Elizabeth MacKintosh (1896-1952) Her play, Richard of Bordeaux (written as Gordon Daviot) was celebrated in its day, and was produced by – and starred – John Gielgud. She never married, but a dear friend – perhaps an early romantic attachment – was killed on the Somme in 1916. She remained an enigma – even to friends who thought themselves close – throughout her life. Her funeral was reported thus: