SO FAR: On the morning of 3rd October 1931, in their isolated farmhouse near Waddingham, Annie Priscilla Jackling (left) is found dead in her bed, while on the floor nearby is her husband Robert, grievously wounded. Both have been shot at close range with a twelve bore shotgun. Their child Maurice is unharmed, but standing in in his cot, crying for his mother. The couple’s nephew, sixteen year-old Harold Smith, who lived and worked on the farm, is missing.

Harold Smith’s escape from the scene was hardly a thing of drama. Taking Robert Jackling’s bicycle, he had made it as far as Wrawby, just north of Brigg, when he was arrested, just hours after the grim discovery at Holmes Farm. Superintendent Dolby from Brigg knew that the case, which became a double murder when Robert Jackling died in Lincoln Hospital, offered only three sensible scenarios. First, that this was a murder suicide, Jackling having shot his wife and then turned the gun on himself. Second, that the pair had been shot by an unknown assailant and, third, that the killer was Harold Smith.

Smith made a detailed statement quite soon after his arrest. It implied that he had been brooding for some time over his treatment by Robert Jackling, and had been contemplating taking action. At Smith’s trial at Lincoln Assizes in November, this was reported:

At his trial, Smith resolutely denied having anything at all to do with the murders, and only admitted to hearing gunshots in the night, and subsequently removing the shotgun from the bedroom, and placing it downstairs. He said that he fled the scene, fearing that he would be blamed. Neither Mr Justice Mackinnon (right) nor the jury were having any of this, and he was found guilty and sentenced to death, although the jury made a recommendation that mercy be shown. Invariably, judges had little option but to don the black cap when the charge remained as murder, with no suggestion of the defendant being insane. As there had been no-one hanged at the age of sixteen for decades, it was almost inevitable that the Home Secretary would order a reprieve, and Harold Smith was spared the attentions of the hangman. To me, from a distance of over ninety years, it seems that Harold Smith was guilty of cold blooded murder. The words in his original statement are chilling:

“I stood by the doorway of the bedroom for some minutes, deciding whether to do it or not. At last I touched the trigger.”

There was a long feature article in Thompson’s Weekly News after the reprieve, purportedly written by Smith’s mother. Thompson’s Weekly news was published in Dundee, and the parent company were also proud parents of The Beano. There is little to choose between Mrs Smith’s reported outpourings some of the more unlikely adventures of the Bash Street Kids and Dennis the Menace.

I don’t apportion any blame to Mrs Smith. She clearly was delighted that her son would not be hanged, and being a poor woman,the newspaper’s money would have been welcome, but the article is clearly the work of one of the newspaper’s more inventive hacks and, under the sub-heading reproduced above, contains such comments as:

“Harold was looking exceptionally well, but I noticed that the tears were not far from his eyes. Indeed, l am sure he would have broken down if we had not had our friend with us, Even then, if we had not turned the conversation round to the happy days he had spent on the farm after leaving school, he would not have managed to keep a stiff upper lip.”

“I could not take in what was happening. My poor boy sentenced to die by the hangman’s rope! Oh no! Surely there was some mistake.”

The 1939 register shows that Harold Smith was in Maidstone Prison. We also know that he was released on licence in June 1941, slightly less than ten years since the brutal killing for which was adjudged responsible. He was still younger than either of his victims. He died at the age of 78 in January 1998, in Crewe. The last surviving witness to the tragedy was the child who stood in his cot as the dreadful event took place. Maurice Jackling died in 2003, also at the age of 78.

We know that Holmes Farm was still occupied in 1939, because Harry Dickinson, who farmed there, was the victim of pig-rustling by a couple of his workers. The property was advertised as a vacant possession in April 1945, but I believe it was derelict and had been pulled down by 1950, as in 1952 a property known as New Holmes Farm, built just down the lane, was advertised as “an excellent modern farmhouse and range of buildings, both erected since the war.”

I would like to thank Mick Lake for help with researching this case.

I have been researching and writing about historic Lincolnshire murders for some years,and those wishing to find out more about our county’s macabre past should click this link.

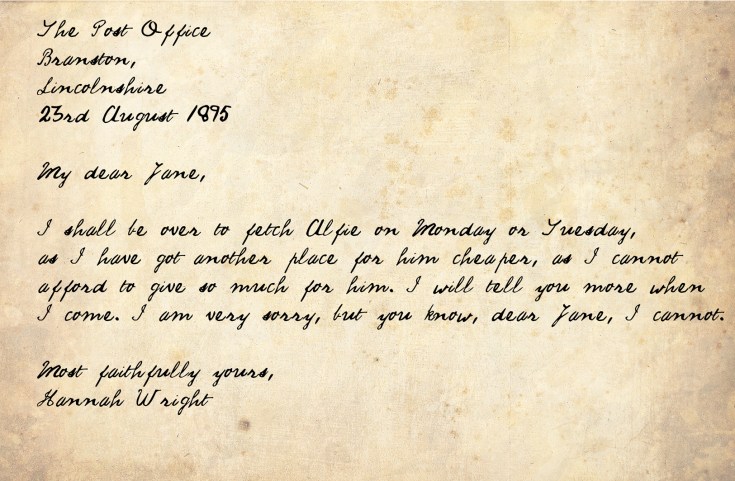

James Fenton had contacted the police with his suspicions, and the discovery of the body confirmed the police’s worst fears. It is not entirely clear how the police knew exactly where to find the mystery woman, but on the Tuesday, they paid several visits to the house at 25 Alexandra Terrace. Hannah Wright, however, was nowhere to be found. She had left that morning, telling her sister-in-law that she was going to visit friends. She did not return until the Wednesday morning, by which time the police had instituted a full scale murder investigation. Hannah confessed to Jane Wright, and a neighbour, Mrs Sarah Close. It was Mrs Close who accompanied Hannah to the police station, but the girl seemed to be under the bizarre misapprehension that if she told the truth she would get away with a ‘telling off’ or, at worst, a fine. She was not to be so fortunate:

James Fenton had contacted the police with his suspicions, and the discovery of the body confirmed the police’s worst fears. It is not entirely clear how the police knew exactly where to find the mystery woman, but on the Tuesday, they paid several visits to the house at 25 Alexandra Terrace. Hannah Wright, however, was nowhere to be found. She had left that morning, telling her sister-in-law that she was going to visit friends. She did not return until the Wednesday morning, by which time the police had instituted a full scale murder investigation. Hannah confessed to Jane Wright, and a neighbour, Mrs Sarah Close. It was Mrs Close who accompanied Hannah to the police station, but the girl seemed to be under the bizarre misapprehension that if she told the truth she would get away with a ‘telling off’ or, at worst, a fine. She was not to be so fortunate:

The law took its inevitable course. There was a coroner’s inquest, then a magistrate’s hearing, both of which judged that Hannah Wright had murdered her little boy. As was customary, the magistrate passed the case on to be heard at next Assizes. Meanwhile Alfie’s body was laid to rest in a lonely ceremony at Canwick Road cemetery. It is pointless speculating about Hannah’s state of mind, but it is worth reminding ourselves that Alfie had known no father and had seen very little of his mother during his brief sojourn – fewer than 300 days – on earth. If ever there were a case of ‘Suffer the little children’ this must be it.

The law took its inevitable course. There was a coroner’s inquest, then a magistrate’s hearing, both of which judged that Hannah Wright had murdered her little boy. As was customary, the magistrate passed the case on to be heard at next Assizes. Meanwhile Alfie’s body was laid to rest in a lonely ceremony at Canwick Road cemetery. It is pointless speculating about Hannah’s state of mind, but it is worth reminding ourselves that Alfie had known no father and had seen very little of his mother during his brief sojourn – fewer than 300 days – on earth. If ever there were a case of ‘Suffer the little children’ this must be it.

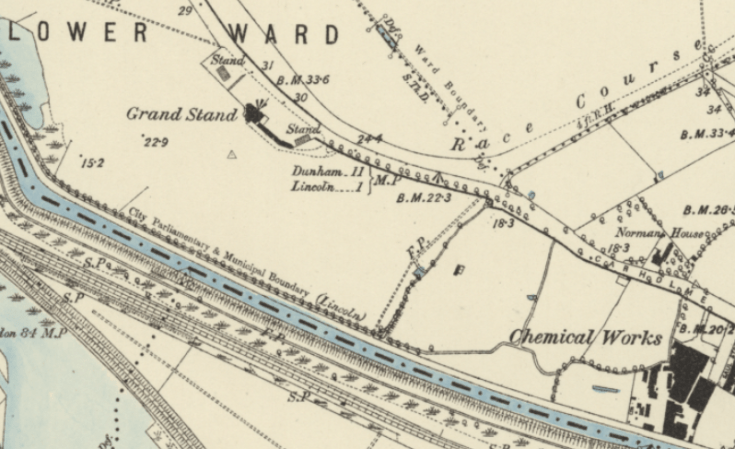

Having traveled to Lincoln on the afternoon of 23rd August, Hannah visited her brother and his wife at their house, 23 Alexandra Terrace. All appeared to well, and on the Sunday evening Hannah even brought her young man, William Spurr, round for tea.

Having traveled to Lincoln on the afternoon of 23rd August, Hannah visited her brother and his wife at their house, 23 Alexandra Terrace. All appeared to well, and on the Sunday evening Hannah even brought her young man, William Spurr, round for tea.

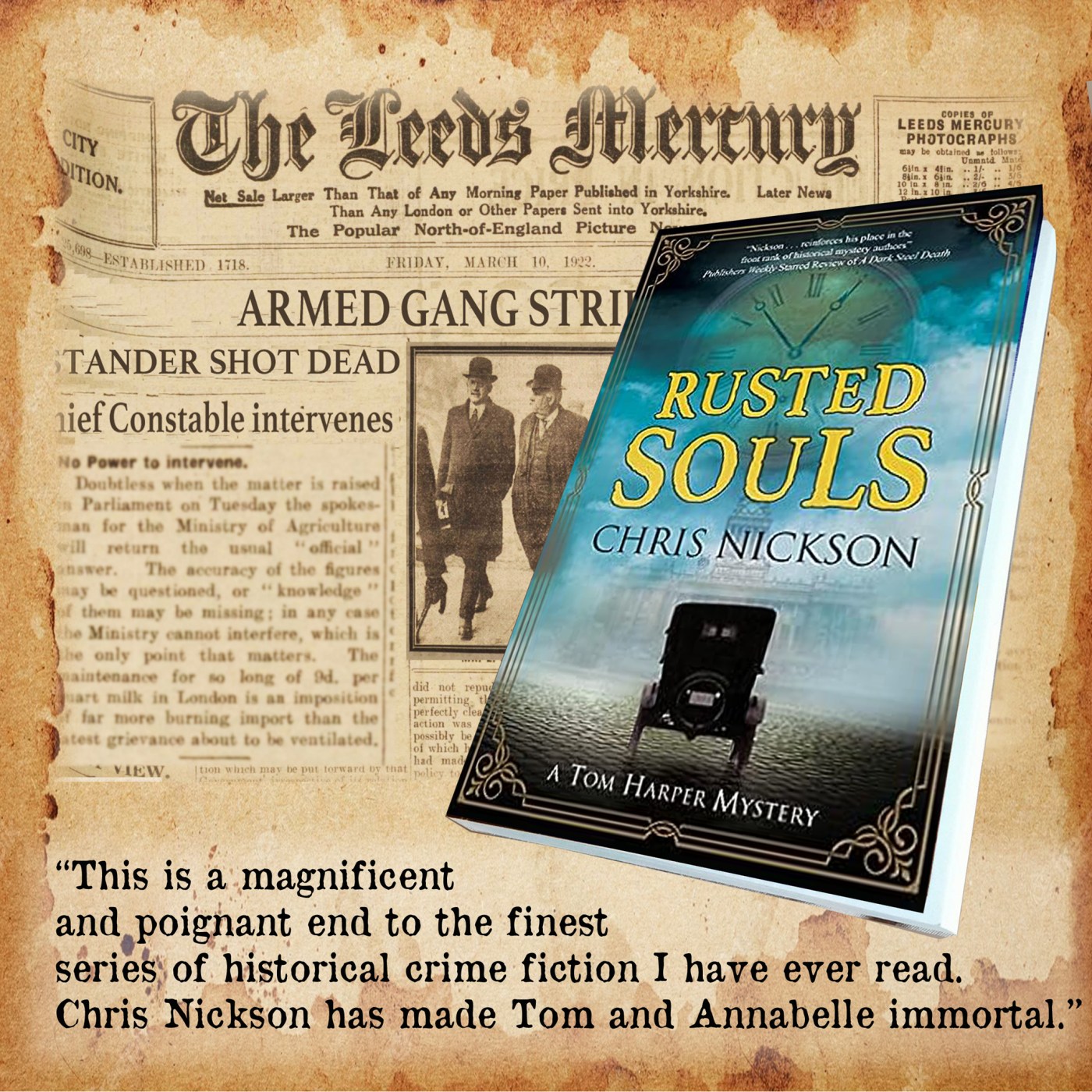

Leeds, March 1920. Tom Harper is Chief Constable of the City force and, with just six weeks until his retirement, he is dearly hoping for a quiet ride home for the final furlong of what has been a long and distinguished career. His hopes are dashed, however, when he is summoned to the office of Alderman Ernest Thompson, the combative, blustering – but very powerful – leader of the City Council. Thompson has one last task for Harper, and it is a very delicate one. The politician has fallen a trap that is all too familiar to many elderly men of influence down the years. He has, shall we say, been indiscreet with a beautiful but much younger woman, Charlotte Radcliffe. Letters that he foolishly wrote to her have “gone missing” and now he has an anonymous note demanding money – or else his reputation will be ruined. He wants Harper to solve the case, but keep everything completely off the record. Grim-faced, Harper has little choice but to agree. It is due to Thompson’s support and encouragement that he is ending his career as Chief Constable, with a comfortable pension and an untarnished reputation. He chooses a small group of trusted colleagues, swears them to secrecy, and sets about the investigation.

Leeds, March 1920. Tom Harper is Chief Constable of the City force and, with just six weeks until his retirement, he is dearly hoping for a quiet ride home for the final furlong of what has been a long and distinguished career. His hopes are dashed, however, when he is summoned to the office of Alderman Ernest Thompson, the combative, blustering – but very powerful – leader of the City Council. Thompson has one last task for Harper, and it is a very delicate one. The politician has fallen a trap that is all too familiar to many elderly men of influence down the years. He has, shall we say, been indiscreet with a beautiful but much younger woman, Charlotte Radcliffe. Letters that he foolishly wrote to her have “gone missing” and now he has an anonymous note demanding money – or else his reputation will be ruined. He wants Harper to solve the case, but keep everything completely off the record. Grim-faced, Harper has little choice but to agree. It is due to Thompson’s support and encouragement that he is ending his career as Chief Constable, with a comfortable pension and an untarnished reputation. He chooses a small group of trusted colleagues, swears them to secrecy, and sets about the investigation.