AUGUST, 1865. Queen Victoria was in the 28th year of her reign, but had become a virtual recluse after the death of Prince Albert in 1861. Palmerston was Prime Minister, and the Salvation Army had been founded in Whitechapel. In America, the Civil War was over, but Lincoln was dead, and Andrew Johnson ruled in his stead.

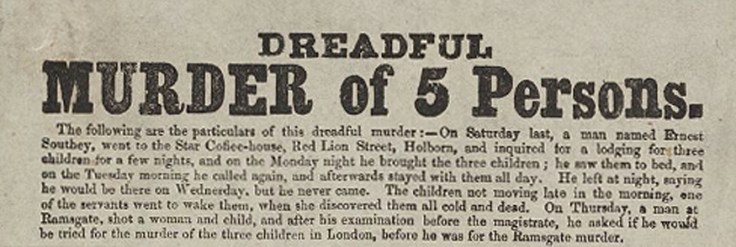

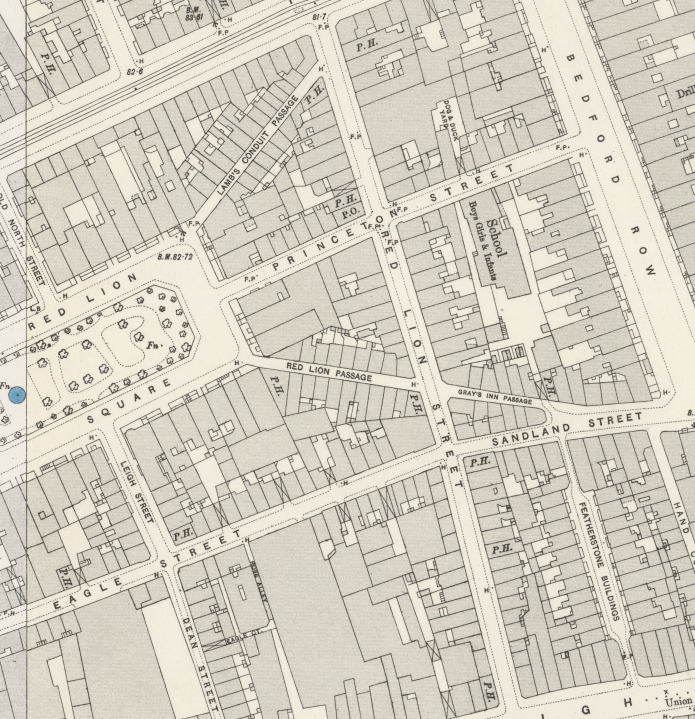

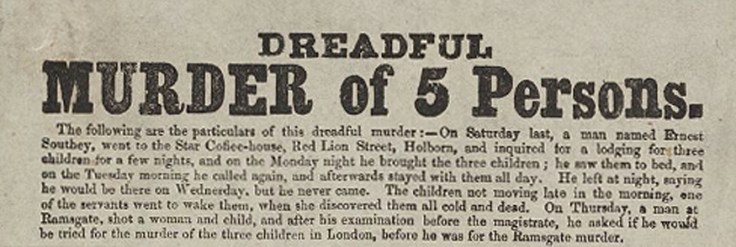

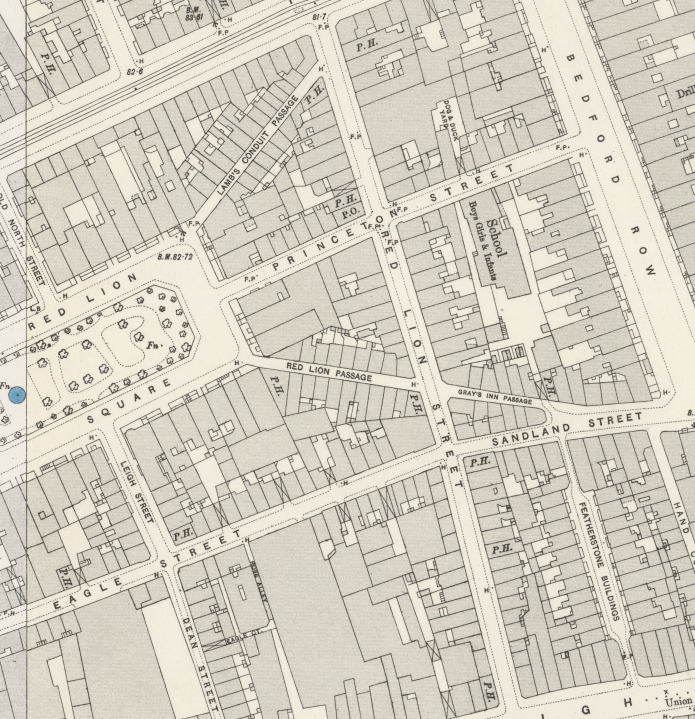

On the evening of Monday 7th August, a man brought three children, aged six, eight and ten, to the Star Coffee House and Hotel, Red Lion Street, Holborn, London. He had previously arranged accommodation, saying that they would all shortly be leaving for Australia. On the Tuesday evening, he put the children to bed and left the hotel, stating that he world return shortly. On the Wednesday morning, neither the man nor the children came down for breakfast. Sensing that something was wrong, the hotel manager entered the rooms occupied by the children, and found a terrible sight. All three were quite dead, and there was no sign of the man.

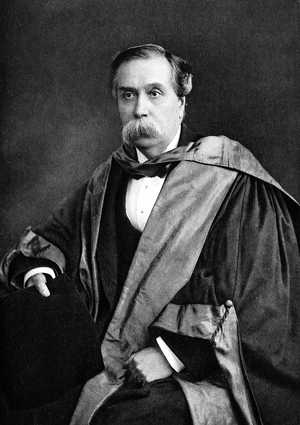

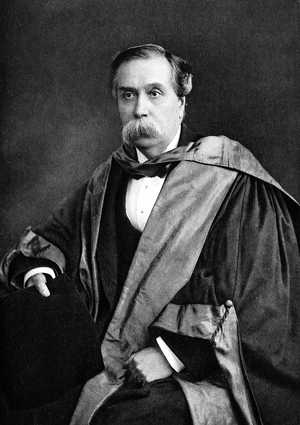

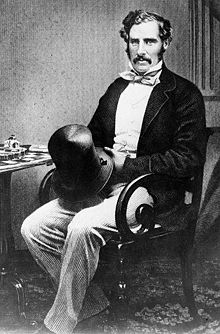

The testimony of Dr George Harley, physician, (below right) was this:

“On the 9th of August last I was requested by Dr. ROBERTS, of Lamb’s Conduit-street to visit Star’s Hotel, where, as he informed me, three children were supposed to have been murdered, and that in case of so serious a nature he deemed it advisable to have a second opinion. On the third floor, in the front room, No. 6 of the above-named hotel I saw two boys lying on their backs in bed quite dead. The younger of the two, ALEXANDER WHITE, aged eight was near the back, the elder, THOMAS WILLIAM WHITE, aged nine years, toward the front part of the bed. The bodies of both were cold and stiff, and although their countenances wore the placidity of slumber they nevertheless bore the pallor of death. The eyes were half open; the pupils semi-dilated. On turning down the bedclothes both bodies presented a mottled appearance, from the extreme lividity of some parts, the deadly pallor of others. The attitude of the youngest child was that of a comfortable repose. The head slightly inclined to the left side. The hands were folded upon the abdomen. The legs gently crossed. The fingers of the right hand still retained within them a penny-piece, which fell from their stiffened grasp while the body was being turned upon its side, with the view of detecting marks of violence.”

“On the 9th of August last I was requested by Dr. ROBERTS, of Lamb’s Conduit-street to visit Star’s Hotel, where, as he informed me, three children were supposed to have been murdered, and that in case of so serious a nature he deemed it advisable to have a second opinion. On the third floor, in the front room, No. 6 of the above-named hotel I saw two boys lying on their backs in bed quite dead. The younger of the two, ALEXANDER WHITE, aged eight was near the back, the elder, THOMAS WILLIAM WHITE, aged nine years, toward the front part of the bed. The bodies of both were cold and stiff, and although their countenances wore the placidity of slumber they nevertheless bore the pallor of death. The eyes were half open; the pupils semi-dilated. On turning down the bedclothes both bodies presented a mottled appearance, from the extreme lividity of some parts, the deadly pallor of others. The attitude of the youngest child was that of a comfortable repose. The head slightly inclined to the left side. The hands were folded upon the abdomen. The legs gently crossed. The fingers of the right hand still retained within them a penny-piece, which fell from their stiffened grasp while the body was being turned upon its side, with the view of detecting marks of violence.”

He continued:

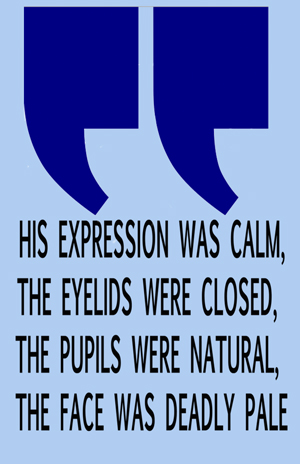

“In the back bedroom, No. 8, of the same floor lay the dead body of a somewhat emaciated but handsomely featured boy, HENRY WILLIAM WHITE, aged ten years. The attitude and complexion of this child closely resembled that of his brothers. His expression was calm, the eyelids were closed, the pupils were natural, the face was deadly pale. A small quantity of fluid had flowed from the mouth on to the collar of his shirt, and that part of the left cheek in contact with it was mottled red and purple. The legs and toes were slightly bent the hands partially closed, the nails and finger tips intensely livid. A spot of feculent matter soiled the sheet. The rigidity of death was well marked in every l imb, and livid discolorations in all the depending parts of the body. No marks of violence were observable, but a slight odor was perceptible about the mouth. The whole chamber had a peculiar ethereal smell.”

“In the back bedroom, No. 8, of the same floor lay the dead body of a somewhat emaciated but handsomely featured boy, HENRY WILLIAM WHITE, aged ten years. The attitude and complexion of this child closely resembled that of his brothers. His expression was calm, the eyelids were closed, the pupils were natural, the face was deadly pale. A small quantity of fluid had flowed from the mouth on to the collar of his shirt, and that part of the left cheek in contact with it was mottled red and purple. The legs and toes were slightly bent the hands partially closed, the nails and finger tips intensely livid. A spot of feculent matter soiled the sheet. The rigidity of death was well marked in every l imb, and livid discolorations in all the depending parts of the body. No marks of violence were observable, but a slight odor was perceptible about the mouth. The whole chamber had a peculiar ethereal smell.”

He concluded:

“I have to add that the history of the cases, the appearance and attitudes of the bodies after death, the result of the post mortem examinations, and the chemical analysis lead me to the conclusion that Henry William White, Thomas William White, and Alexander White died from the mortal effects of a poisonous dose of prussic acid.”

The three dead children were identified as Henry White, aged ten years,Thomas White, aged eight years and Alexander White, aged six years. The parenting of these three children had been bizarre, to say the least. Their father – or at least the man who accepted them as his own – had been married to the boys’ mother, and by an awful coincidence was a schoolmaster in Featherstone Buildings, only a stone’s throw from the hotel where they died.

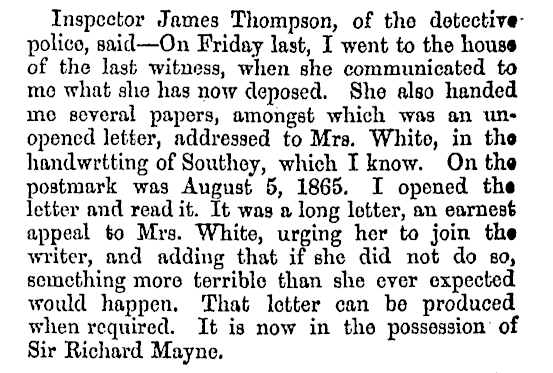

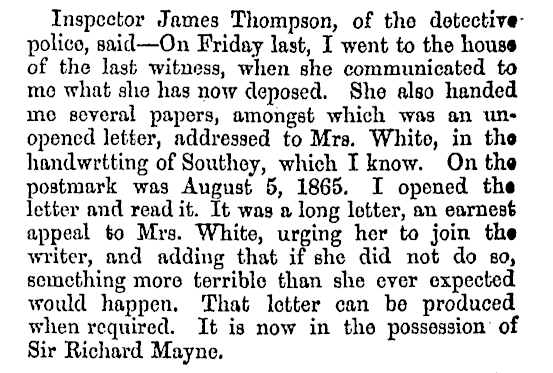

The boys’ mother had been living with a man called Ernest Southey, and the three lads had been passed backwards and forwards several times between Mr William Henry White and his wife. Finally, they had been ‘in the care’ of Southey and Mrs White, as it was put about that they intended to emigrate to Australia. Not only did Mr White’s description of Southey match that of the hotel staff, Southey was known to the police. Earlier in the year, Southey, who was, by occupation a billiard marker, had been involved in a strange case where Mrs White tried to inveigle money from a member of the aristocracy, and Southey had intervened on her behalf.

The Home Secretary, Sir George Grey (left), announced a £100 reward for the apprehension of Southey. It was to prove unnecessary. Having poisoned the three boys, the fugitive, who obviously subscribed to the old adage about sheep and lambs, had traveled down to the Kent seaside town of Ramsgate where, it transpired, his real wife and daughter lived. Having met them, and pleaded for their forgiveness for his long absence and neglect, he then shot them both dead with a pistol. He was caught red-handed, and gave himself up without a struggle.

The Home Secretary, Sir George Grey (left), announced a £100 reward for the apprehension of Southey. It was to prove unnecessary. Having poisoned the three boys, the fugitive, who obviously subscribed to the old adage about sheep and lambs, had traveled down to the Kent seaside town of Ramsgate where, it transpired, his real wife and daughter lived. Having met them, and pleaded for their forgiveness for his long absence and neglect, he then shot them both dead with a pistol. He was caught red-handed, and gave himself up without a struggle.

At this point it became clear that Ernest Southey was none other than Stephen Forwood, his latest victims being Mary Ann Jemima Forward, and her daughter Emily. He was brought to the magistrate in Ramsgate, but then produced an astonishing document, apparently penned in the interval between his arrest and the court appearance. He proclaimed to the court;

“On Monday, the 7th instant, I took three children, whom I claim as mine by the strongest ties, to Starr’s Coffee-house, Red Lion-street, Holborn. I felt for these children all the affection a parent could feel. I had utterly worn out and exhausted every power of mind and body in my efforts to secure a home, training, and a future for those children, also the five persons I felt hopelessly dependent on me. I could struggle and bear up no longer, for the last support had been withdrawn from me. My sufferings were no longer supportable. My very last hope had perished by my bitter and painful experience of our present iniquitously-ineffective social justice, and for this I shall be  charged with murder, for criminal murders as well in the truest, strongest sense of the charge. I deny and repudiate the charge, and charge it back on many who have by their gross and criminal neglect brought about this sad and fearful crisis. I charge back the guilt of these crimes on those high dignitaries of the State, the Church, and justice who have turned a deaf ear to my heartbroken appeals, who have refused me fellow help in all my frenzied efforts, my exhausted struggles; who have impiously denied the sacredness of human life, the mutual dependence of man, and the fundamental and sacred principles on which our social system is based. Foremost among these I charge the Hon. D. Lord Palmerston, the Attorney General, Sir George Grey, the Hon. Mr. Gladstone, the Earl of Shaftesbury, Lord Ebury, Lord Townshend, Lord Elcho, Lord Brougham, Sir E. B Lytton, Mr Disraeli, Sir J. Packington, Earl Derby, Lord Stanley, Mr Crossley, and the Bishop of Bath and Wells. I Under all the terrible run of my life I have done for the best.”

charged with murder, for criminal murders as well in the truest, strongest sense of the charge. I deny and repudiate the charge, and charge it back on many who have by their gross and criminal neglect brought about this sad and fearful crisis. I charge back the guilt of these crimes on those high dignitaries of the State, the Church, and justice who have turned a deaf ear to my heartbroken appeals, who have refused me fellow help in all my frenzied efforts, my exhausted struggles; who have impiously denied the sacredness of human life, the mutual dependence of man, and the fundamental and sacred principles on which our social system is based. Foremost among these I charge the Hon. D. Lord Palmerston, the Attorney General, Sir George Grey, the Hon. Mr. Gladstone, the Earl of Shaftesbury, Lord Ebury, Lord Townshend, Lord Elcho, Lord Brougham, Sir E. B Lytton, Mr Disraeli, Sir J. Packington, Earl Derby, Lord Stanley, Mr Crossley, and the Bishop of Bath and Wells. I Under all the terrible run of my life I have done for the best.”

Whether the wretched man was exhibiting an early version of what we would come to know as The Blackadder Defence – wearing underpants on the head and sticking knitting needles up the nostrils, in the hope that he would be considered totally mad – we shall never know. Forward’s lawyer half-heartedly went for a plea of insanity, but his efforts were ignored.

Whether the wretched man was exhibiting an early version of what we would come to know as The Blackadder Defence – wearing underpants on the head and sticking knitting needles up the nostrils, in the hope that he would be considered totally mad – we shall never know. Forward’s lawyer half-heartedly went for a plea of insanity, but his efforts were ignored.

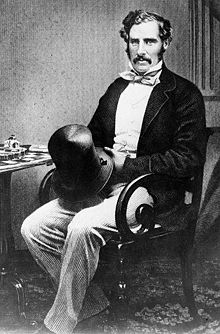

The authorities in London wanted Forward returned to them, but the Kent police had him under lock and key, and they had no intention of letting him go. Regarding the murder of the boys, Forward’s trial produced evidence that Mrs White had grown tired of him, and he had threatened her with dire consequences should she not take him back. He was sentenced to death, and was eventually executed in January 1866. A local newspaper takes up the story.

On 11 January 1866, at the County Goal in Maidstone one of the most notorious murderers of Victorian Kent paid the final penalty for his crimes. This was Stephen Forwood (or Forwood) also known as Ernest Walter Southey. He was the last person to be publicly executed at Maidstone Goal (below)

A contemporary account tells us:

The morning of Thursday 11 January 1866, was very cold, a severe snow storm driven by a harsh wind prevailed and this kept the usual crowd that gathered for this occasion down to about 1500 persons. The execution was presided over by Mr. F Scudamore, the Under-Sheriff of the County of Kent accompanied by some of his officers.

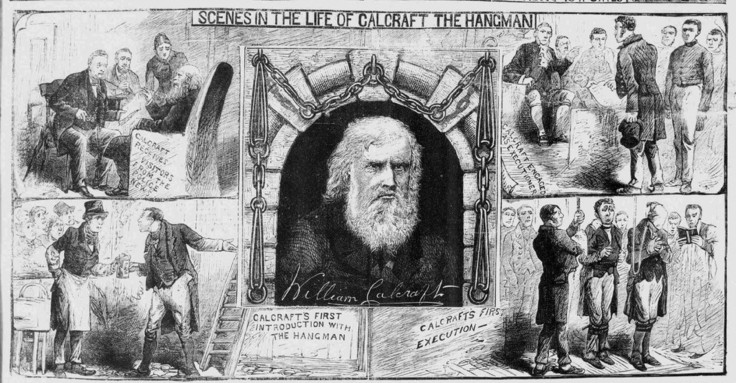

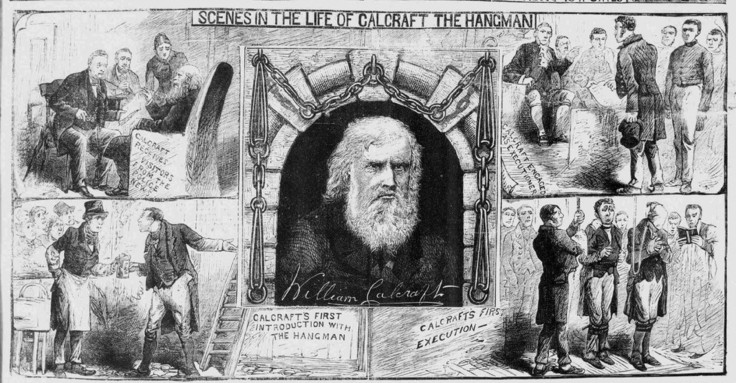

Arriving at the Gaol just before midday they immediately went to the cell where Forward was held. The executioner was Calcraft who acted as executioner at Stafford and in the “Midland Counties”. The prisoner asked for permission to speak and “exclaimed in an audible voice”, ” I desire to say in the presence of you who are now assembled, and in the presence of Almighty God, into whose immediate presence I am now about to depart, that I die trusting only to the merits of the God-man Jesus Christ”.

Arriving at the Gaol just before midday they immediately went to the cell where Forward was held. The executioner was Calcraft who acted as executioner at Stafford and in the “Midland Counties”. The prisoner asked for permission to speak and “exclaimed in an audible voice”, ” I desire to say in the presence of you who are now assembled, and in the presence of Almighty God, into whose immediate presence I am now about to depart, that I die trusting only to the merits of the God-man Jesus Christ”.

The prisoner was now “pinioned” by Calcraft (above) and as he was lead to the scaffold he could be heard praying loudly. Just before he was placed on the drop he shook hands with Major Bannister, the Governor of the Gaol, and with the chaplain. To the chaplain he made his last request that when he was upon the scaffold the chaplain would only utter the following prayer” Lord, into thy hands we commend the soul of this our brother, for thou hast redeemed him. Oh Lord, thou God of Troth.”

Forward said that his reason for this request was that he wished to “concentrate the whole powers of his soul and spirit into one mighty act of volition, and render himself up to God in the words mentioned.” The request was granted and as the chaplain began to speak, the drop opened and Forward “ceased to exist”.

The Maidstone and Kentish Journal describes the scene so:

The scaffold was hung round with black cloth to such a height that when the drop fell only just the top of the convict’s head was visible to the crowd. The body, after hanging an hour, was cut down and a cast of the head taken. In the afternoon the body was buried within the precincts of the gaol.

Edwin Ruck, the Registrar for the East Maidstone District, registered the death on Saturday 13 January 1866. The informant being the Governor of the Gaol, Major C W Bannister, the cause of death was stated as “Hanging for Murder’.

We cannot know if Stephen Forwood’s piety on the scaffold stood him in any stead in the place where he was heading, but we can state that it did absolutely no good to the four children and the woman for whose deaths he was responsible. Of the London sites connected with the case little or nothing remains. Where The Star Coffee House and Hotel once stood, at 21 Red Lion Street, we now find a nondescript, but doubtlessly very expensive block of flats. The Featherstone Buildings, where William White taught his grammar lessons, was totally destroyed by German bombs during the Blitz.

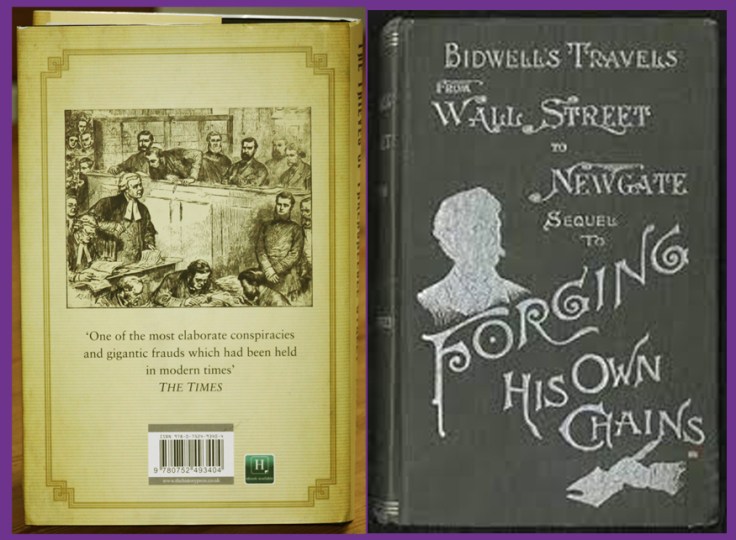

Just as tabloid newspapers, even in this digital age, still hope that a juicy headline will shift a few more copies, the ballad writers and hacks who turned out broadsides may have seen a temporary upsurge in sales, as they dramatised the terrible events of August 1865.

The sounds and sweet airs might have been provided by Haydn Woods’ A Brown Bird Singing or, if you were more disposed towards the art of Edith Sitwell, William Walton’s setting of her poetry – Façade. The discordant sounds of the thousand twangling instruments could have come from several sources; possibly the thousands of impoverished ex-servicemen sold short by the country they had fought for; perhaps, however, the isle which was most full of noises was that of Ireland, and in particular the newly formed Irish Republic.

The sounds and sweet airs might have been provided by Haydn Woods’ A Brown Bird Singing or, if you were more disposed towards the art of Edith Sitwell, William Walton’s setting of her poetry – Façade. The discordant sounds of the thousand twangling instruments could have come from several sources; possibly the thousands of impoverished ex-servicemen sold short by the country they had fought for; perhaps, however, the isle which was most full of noises was that of Ireland, and in particular the newly formed Irish Republic. Sir Henry Wilson was a former General in the British Army, and his contribution to events in The Great War divides opinion. Some have him firmly in the ‘Butchers and Bunglers’ camp, a stereotypical Brass Hat who send brave men off into battle to meet red hot shards of flying steel with their own mortal flesh. Others will say that he was part of the combined military effort which defeated Germany in the field, and led to the surrender in the railway carriage at Compiègne in 1918. Whatever the truth, Wilson was never a field commander. He was much more at home well behind the front line, hobnobbing with politicians and strategists.

Sir Henry Wilson was a former General in the British Army, and his contribution to events in The Great War divides opinion. Some have him firmly in the ‘Butchers and Bunglers’ camp, a stereotypical Brass Hat who send brave men off into battle to meet red hot shards of flying steel with their own mortal flesh. Others will say that he was part of the combined military effort which defeated Germany in the field, and led to the surrender in the railway carriage at Compiègne in 1918. Whatever the truth, Wilson was never a field commander. He was much more at home well behind the front line, hobnobbing with politicians and strategists.

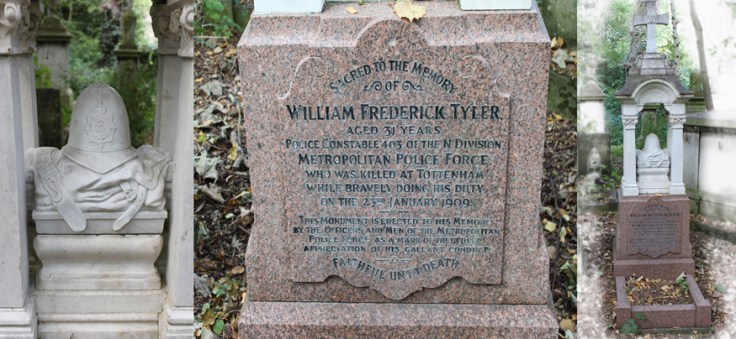

Ralph Joscelyne’s mother, Louise, was to raise another seven children, but she kept the pair of boots Ralph was wearing on the day he was killed. When she died in 1952, the boots were buried with her. In more recent times, both Joscelyne and Tyler have been commemorated. WIlliam Tyler has a plaque on the wall of Tottenham police station, while Ralph Joscelyne is remembered in a memorial outside a church in Mitchley Road. There is an abiding irony that the corner of Tottenham where the robbery occurred and the resultant chase began is exactly where the catastrophic riots of 2011 started. An initially peaceful protest by relatives of Mark Duggan, a gangster shot by police, did not get the required response from officers within the police station. It then, as they say, “all kicked off.”

Ralph Joscelyne’s mother, Louise, was to raise another seven children, but she kept the pair of boots Ralph was wearing on the day he was killed. When she died in 1952, the boots were buried with her. In more recent times, both Joscelyne and Tyler have been commemorated. WIlliam Tyler has a plaque on the wall of Tottenham police station, while Ralph Joscelyne is remembered in a memorial outside a church in Mitchley Road. There is an abiding irony that the corner of Tottenham where the robbery occurred and the resultant chase began is exactly where the catastrophic riots of 2011 started. An initially peaceful protest by relatives of Mark Duggan, a gangster shot by police, did not get the required response from officers within the police station. It then, as they say, “all kicked off.”

We are in the weeks leading up to Christmas 1944, deep in what would prove to be the last winter of a war which, thanks to the Luftwaffe, had brought death and destruction to the doorsteps of ordinary people in towns and cities up and down the country. German aircraft no longer drone over the streets of London; instead, the Dorniers and Heinkels have been replaced by an even more demoralising menace – the seemingly random strikes by V1 and V2 rockets. Despite the fact that the rockets need no visible target to aim at, the ubiquitous blackout is still in force. An Air Raid Precaution Warden, whose job has become as redundant as that of those manning anti-aircraft batteries, makes a chilling discovery. He stumbles – literally – on the body of a young woman. Her neck has been broken by someone clearly well-versed in killing, and the only clue is a number of spent matches lying by the body.

We are in the weeks leading up to Christmas 1944, deep in what would prove to be the last winter of a war which, thanks to the Luftwaffe, had brought death and destruction to the doorsteps of ordinary people in towns and cities up and down the country. German aircraft no longer drone over the streets of London; instead, the Dorniers and Heinkels have been replaced by an even more demoralising menace – the seemingly random strikes by V1 and V2 rockets. Despite the fact that the rockets need no visible target to aim at, the ubiquitous blackout is still in force. An Air Raid Precaution Warden, whose job has become as redundant as that of those manning anti-aircraft batteries, makes a chilling discovery. He stumbles – literally – on the body of a young woman. Her neck has been broken by someone clearly well-versed in killing, and the only clue is a number of spent matches lying by the body. There is more than a touch of The Golden Age about this novel, but it is much more than a pastiche. Although the killing of Rosa Nowak is eventually solved, with a regulation dramatic climax in a snow-bound country house, Rennie Airth allows us to breathe, smell and taste the air of an England almost – but not quite – beaten down by the privations of war. Many of the characters have menfolk away at the war, including Madden himself and his wife Helen. Their son is in the Royal Navy, on the rough winter seas escorting convoys. The contrast between life in the city and in the country is etched deep. In the city, restaurant meals are frequently inedible, the black market thrives unchecked due to depleted police manpower, and even the newsprint bearing cheering propaganda from the government is subject to rationing. Travelling anywhere, unless you are fiddling your petrol coupons, is arduous and unpleasant.

There is more than a touch of The Golden Age about this novel, but it is much more than a pastiche. Although the killing of Rosa Nowak is eventually solved, with a regulation dramatic climax in a snow-bound country house, Rennie Airth allows us to breathe, smell and taste the air of an England almost – but not quite – beaten down by the privations of war. Many of the characters have menfolk away at the war, including Madden himself and his wife Helen. Their son is in the Royal Navy, on the rough winter seas escorting convoys. The contrast between life in the city and in the country is etched deep. In the city, restaurant meals are frequently inedible, the black market thrives unchecked due to depleted police manpower, and even the newsprint bearing cheering propaganda from the government is subject to rationing. Travelling anywhere, unless you are fiddling your petrol coupons, is arduous and unpleasant.

There is, perhaps, a legitimate debate to be had over what to call killings which are carried out in the name of a political cause. No-one in their right mind would label the millions of soldiers who died in the two world wars of the 20th century as murder victims. The wearing of a uniform, and the acceptance of the King’s shilling has always legitimised the act of pulling the trigger, firing the shell, or dropping the bomb.

There is, perhaps, a legitimate debate to be had over what to call killings which are carried out in the name of a political cause. No-one in their right mind would label the millions of soldiers who died in the two world wars of the 20th century as murder victims. The wearing of a uniform, and the acceptance of the King’s shilling has always legitimised the act of pulling the trigger, firing the shell, or dropping the bomb.

Just a couple of hours later, as emergency services struggled to deal with the mayhem in South Carriage Drive, the terrorists struck again. It seems barely credible that in another part of the city, life was going on as normal. Remember, though, that these were the days before mobile ‘phones and social media, the days when news was only transmitted in print, by word of mouth and on radio and television. The regimental band of The Royal Green Jackets was entertaining a small crowd clustered round the bandstand in Regent’s Park. They were playing distinctly un-martial music from the musical ‘Oliver!’ when, at 12.55 pm, a massive bomb went off beneath the bandstand. The blast was so powerful that one of the bodies was thrown onto an iron fence thirty yards away, and seven bandsmen were killed outright. They were: Warrant Officer Graham Barker, Serjeant Robert “Doc” Livingstone, Corporal Johnny McKnight, Bandsman John Heritage, Bandsman George Mesure, Bandsman Keith “Cozy” Powell, and Bandsman Larry Smith.

Just a couple of hours later, as emergency services struggled to deal with the mayhem in South Carriage Drive, the terrorists struck again. It seems barely credible that in another part of the city, life was going on as normal. Remember, though, that these were the days before mobile ‘phones and social media, the days when news was only transmitted in print, by word of mouth and on radio and television. The regimental band of The Royal Green Jackets was entertaining a small crowd clustered round the bandstand in Regent’s Park. They were playing distinctly un-martial music from the musical ‘Oliver!’ when, at 12.55 pm, a massive bomb went off beneath the bandstand. The blast was so powerful that one of the bodies was thrown onto an iron fence thirty yards away, and seven bandsmen were killed outright. They were: Warrant Officer Graham Barker, Serjeant Robert “Doc” Livingstone, Corporal Johnny McKnight, Bandsman John Heritage, Bandsman George Mesure, Bandsman Keith “Cozy” Powell, and Bandsman Larry Smith. Downey (right) may or may not have been implicated in the Hyde Park murders. Only he knows for certain. At least he had the decency to cancel a party planned in his honour when he was released. He said:

Downey (right) may or may not have been implicated in the Hyde Park murders. Only he knows for certain. At least he had the decency to cancel a party planned in his honour when he was released. He said:

Kelly, met a bloody end in her Millers Court hovel. Of Brewer, we know very little, but his style can best be illustrated with a brief extract.

Kelly, met a bloody end in her Millers Court hovel. Of Brewer, we know very little, but his style can best be illustrated with a brief extract. Belloc-Lowndes (right) was the older sister of the prolific writer and poet Hilaire Belloc, but she avoided her brother’s antimodern polemicism, and wrote biographies, plays – and novels which were very highly thought of for their subtlety and psychological insight into crime, although she preferred not to be thought of as a crime fiction writer. In The Lodger, Mr and Mrs Bunting have staked their life savings on buying a house big enough to take in paying guests, but just as their dream is on the verge of crumbling, salvation comes in the form of the mysterious Mr Sleuth, who knocks on the door and takes a room, paying up front with many a gold sovereign. As Mr and Mrs Bunting count their money – and their blessings – London is gripped with terror as a killer nicknamed ‘The Avenger’ stalks the streets searching for blood. The Buntings’ peace of mind evaporates as they suspect that their lodger is none other than The Avenger. Such is the quality of The Lodger that it has been filmed many times, most notably by Alfred Hitchcock in 1927. It would be remiss of me not to quote the famous bloodcurdling imprecation at the end of the book, directed at the hapless landlady.

Belloc-Lowndes (right) was the older sister of the prolific writer and poet Hilaire Belloc, but she avoided her brother’s antimodern polemicism, and wrote biographies, plays – and novels which were very highly thought of for their subtlety and psychological insight into crime, although she preferred not to be thought of as a crime fiction writer. In The Lodger, Mr and Mrs Bunting have staked their life savings on buying a house big enough to take in paying guests, but just as their dream is on the verge of crumbling, salvation comes in the form of the mysterious Mr Sleuth, who knocks on the door and takes a room, paying up front with many a gold sovereign. As Mr and Mrs Bunting count their money – and their blessings – London is gripped with terror as a killer nicknamed ‘The Avenger’ stalks the streets searching for blood. The Buntings’ peace of mind evaporates as they suspect that their lodger is none other than The Avenger. Such is the quality of The Lodger that it has been filmed many times, most notably by Alfred Hitchcock in 1927. It would be remiss of me not to quote the famous bloodcurdling imprecation at the end of the book, directed at the hapless landlady.

Colin Wilson, who died in 2013, (left) was the kind of man with whom the British establishment, certainly in the 1950s and 60s, was most deeply ill at ease. He was, as much by his own proclamation as that of others, intellectually formidable. He burst on the literary scene in 1957 with The Outsider, a journey through an existential world in the company of, among others, Camus, Nietzsche, Kafka, Sartre, Hermann Hesse and Van Gogh. His novel that concerns us is Ritual In The Dark. Published, after a long gestation, in 1960, it examines how The Ripper legend transposes itself onto the London streets of the late 1950s. It must be remembered that many of the murder sites were still more or less recognisable, at that time, to Ripper afficionados. The tale involves three young men, Gerard Sorme, Oliver Glasp and Austin Nunne. Sorme goes about his life well aware of the significance of past deeds, but also knowing that a present day killer is out and about, emulating the horrors of 1888. Wilson could be said to be one of the pioneers of psychogeography, a linking of past and present much used by modern writers such as Iain Sinclair and Peter Ackroyd. Sorme says,

Colin Wilson, who died in 2013, (left) was the kind of man with whom the British establishment, certainly in the 1950s and 60s, was most deeply ill at ease. He was, as much by his own proclamation as that of others, intellectually formidable. He burst on the literary scene in 1957 with The Outsider, a journey through an existential world in the company of, among others, Camus, Nietzsche, Kafka, Sartre, Hermann Hesse and Van Gogh. His novel that concerns us is Ritual In The Dark. Published, after a long gestation, in 1960, it examines how The Ripper legend transposes itself onto the London streets of the late 1950s. It must be remembered that many of the murder sites were still more or less recognisable, at that time, to Ripper afficionados. The tale involves three young men, Gerard Sorme, Oliver Glasp and Austin Nunne. Sorme goes about his life well aware of the significance of past deeds, but also knowing that a present day killer is out and about, emulating the horrors of 1888. Wilson could be said to be one of the pioneers of psychogeography, a linking of past and present much used by modern writers such as Iain Sinclair and Peter Ackroyd. Sorme says, “I am lying here in the middle of London, with a population of three million people asleep around me,

“I am lying here in the middle of London, with a population of three million people asleep around me,

Stout, florid and perspiring in the heat, William Pinkerton, (left) scion of the famous detective dynasty, had been characteristically indefatigable in tracking down his quarry, travelling from New York to London, and thence to Havana. Glassy eyed, hollow -cheeked and very tired, his prisoner was, in one estimation, “a smooth, easy talker and a person who is likely to inspire confidence with anyone with whom he talked”.

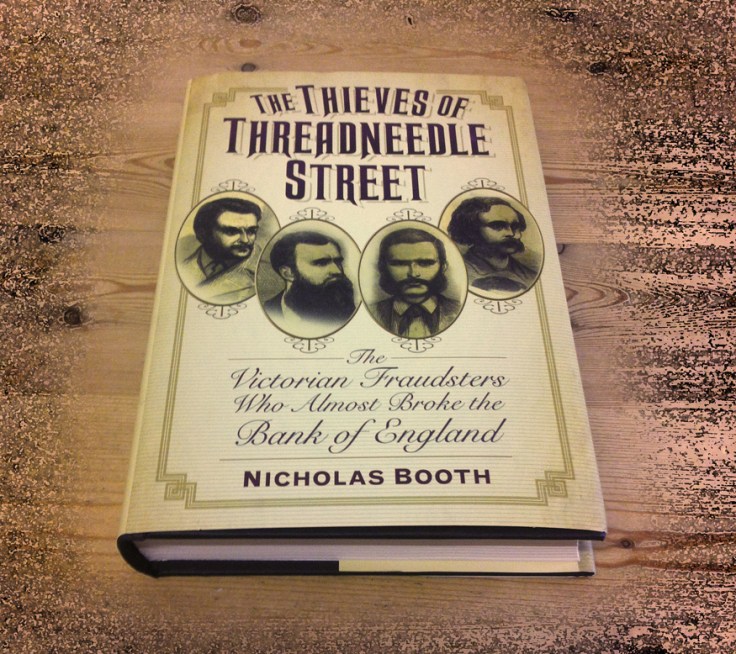

Stout, florid and perspiring in the heat, William Pinkerton, (left) scion of the famous detective dynasty, had been characteristically indefatigable in tracking down his quarry, travelling from New York to London, and thence to Havana. Glassy eyed, hollow -cheeked and very tired, his prisoner was, in one estimation, “a smooth, easy talker and a person who is likely to inspire confidence with anyone with whom he talked”. he was just 27, and along with his eldest brother George (a serial womaniser and ne’er do well) and a couple of accomplices, he had – in Willie Pinkerton’s judgement – carried out the most daring forgery and fraud the world had ever known.

he was just 27, and along with his eldest brother George (a serial womaniser and ne’er do well) and a couple of accomplices, he had – in Willie Pinkerton’s judgement – carried out the most daring forgery and fraud the world had ever known. (left) was a beautiful, naive girl of 18 who had fallen for Austin in the summer of 1872. Austin was a professional American criminal who had recently moved his operations to London. Her family were living in genteel poverty near Marble Arch; and though he would have preferred her as his rich man’s plaything, she declined. It was marriage or nothing. Though assuaged by his self-evident wealth, only later did she find out that her honeymoon had been paid for with stolen money. But by then, it was too late to do anything.

(left) was a beautiful, naive girl of 18 who had fallen for Austin in the summer of 1872. Austin was a professional American criminal who had recently moved his operations to London. Her family were living in genteel poverty near Marble Arch; and though he would have preferred her as his rich man’s plaything, she declined. It was marriage or nothing. Though assuaged by his self-evident wealth, only later did she find out that her honeymoon had been paid for with stolen money. But by then, it was too late to do anything.

“On the 9th of August last I was requested by Dr. ROBERTS, of Lamb’s Conduit-street to visit Star’s Hotel, where, as he informed me, three children were supposed to have been murdered, and that in case of so serious a nature he deemed it advisable to have a second opinion. On the third floor, in the front room, No. 6 of the above-named hotel I saw two boys lying on their backs in bed quite dead. The younger of the two, ALEXANDER WHITE, aged eight was near the back, the elder, THOMAS WILLIAM WHITE, aged nine years, toward the front part of the bed. The bodies of both were cold and stiff, and although their countenances wore the placidity of slumber they nevertheless bore the pallor of death. The eyes were half open; the pupils semi-dilated. On turning down the bedclothes both bodies presented a mottled appearance, from the extreme lividity of some parts, the deadly pallor of others. The attitude of the youngest child was that of a comfortable repose. The head slightly inclined to the left side. The hands were folded upon the abdomen. The legs gently crossed. The fingers of the right hand still retained within them a penny-piece, which fell from their stiffened grasp while the body was being turned upon its side, with the view of detecting marks of violence.”

“On the 9th of August last I was requested by Dr. ROBERTS, of Lamb’s Conduit-street to visit Star’s Hotel, where, as he informed me, three children were supposed to have been murdered, and that in case of so serious a nature he deemed it advisable to have a second opinion. On the third floor, in the front room, No. 6 of the above-named hotel I saw two boys lying on their backs in bed quite dead. The younger of the two, ALEXANDER WHITE, aged eight was near the back, the elder, THOMAS WILLIAM WHITE, aged nine years, toward the front part of the bed. The bodies of both were cold and stiff, and although their countenances wore the placidity of slumber they nevertheless bore the pallor of death. The eyes were half open; the pupils semi-dilated. On turning down the bedclothes both bodies presented a mottled appearance, from the extreme lividity of some parts, the deadly pallor of others. The attitude of the youngest child was that of a comfortable repose. The head slightly inclined to the left side. The hands were folded upon the abdomen. The legs gently crossed. The fingers of the right hand still retained within them a penny-piece, which fell from their stiffened grasp while the body was being turned upon its side, with the view of detecting marks of violence.” “In the back bedroom, No. 8, of the same floor lay the dead body of a somewhat emaciated but handsomely featured boy, HENRY WILLIAM WHITE, aged ten years. The attitude and complexion of this child closely resembled that of his brothers. His expression was calm, the eyelids were closed, the pupils were natural, the face was deadly pale. A small quantity of fluid had flowed from the mouth on to the collar of his shirt, and that part of the left cheek in contact with it was mottled red and purple. The legs and toes were slightly bent the hands partially closed, the nails and finger tips intensely livid. A spot of feculent matter soiled the sheet. The rigidity of death was well marked in every l imb, and livid discolorations in all the depending parts of the body. No marks of violence were observable, but a slight odor was perceptible about the mouth. The whole chamber had a peculiar ethereal smell.”

“In the back bedroom, No. 8, of the same floor lay the dead body of a somewhat emaciated but handsomely featured boy, HENRY WILLIAM WHITE, aged ten years. The attitude and complexion of this child closely resembled that of his brothers. His expression was calm, the eyelids were closed, the pupils were natural, the face was deadly pale. A small quantity of fluid had flowed from the mouth on to the collar of his shirt, and that part of the left cheek in contact with it was mottled red and purple. The legs and toes were slightly bent the hands partially closed, the nails and finger tips intensely livid. A spot of feculent matter soiled the sheet. The rigidity of death was well marked in every l imb, and livid discolorations in all the depending parts of the body. No marks of violence were observable, but a slight odor was perceptible about the mouth. The whole chamber had a peculiar ethereal smell.” The Home Secretary, Sir George Grey (left), announced a £100 reward for the apprehension of Southey. It was to prove unnecessary. Having poisoned the three boys, the fugitive, who obviously subscribed to the old adage about sheep and lambs, had traveled down to the Kent seaside town of Ramsgate where, it transpired, his real wife and daughter lived. Having met them, and pleaded for their forgiveness for his long absence and neglect, he then shot them both dead with a pistol. He was caught red-handed, and gave himself up without a struggle.

The Home Secretary, Sir George Grey (left), announced a £100 reward for the apprehension of Southey. It was to prove unnecessary. Having poisoned the three boys, the fugitive, who obviously subscribed to the old adage about sheep and lambs, had traveled down to the Kent seaside town of Ramsgate where, it transpired, his real wife and daughter lived. Having met them, and pleaded for their forgiveness for his long absence and neglect, he then shot them both dead with a pistol. He was caught red-handed, and gave himself up without a struggle. charged with murder, for criminal murders as well in the truest, strongest sense of the charge. I deny and repudiate the charge, and charge it back on many who have by their gross and criminal neglect brought about this sad and fearful crisis. I charge back the guilt of these crimes on those high dignitaries of the State, the Church, and justice who have turned a deaf ear to my heartbroken appeals, who have refused me fellow help in all my frenzied efforts, my exhausted struggles; who have impiously denied the sacredness of human life, the mutual dependence of man, and the fundamental and sacred principles on which our social system is based. Foremost among these I charge the Hon. D. Lord Palmerston, the Attorney General, Sir George Grey, the Hon. Mr. Gladstone, the Earl of Shaftesbury, Lord Ebury, Lord Townshend, Lord Elcho, Lord Brougham, Sir E. B Lytton, Mr Disraeli, Sir J. Packington, Earl Derby, Lord Stanley, Mr Crossley, and the Bishop of Bath and Wells. I Under all the terrible run of my life I have done for the best.”

charged with murder, for criminal murders as well in the truest, strongest sense of the charge. I deny and repudiate the charge, and charge it back on many who have by their gross and criminal neglect brought about this sad and fearful crisis. I charge back the guilt of these crimes on those high dignitaries of the State, the Church, and justice who have turned a deaf ear to my heartbroken appeals, who have refused me fellow help in all my frenzied efforts, my exhausted struggles; who have impiously denied the sacredness of human life, the mutual dependence of man, and the fundamental and sacred principles on which our social system is based. Foremost among these I charge the Hon. D. Lord Palmerston, the Attorney General, Sir George Grey, the Hon. Mr. Gladstone, the Earl of Shaftesbury, Lord Ebury, Lord Townshend, Lord Elcho, Lord Brougham, Sir E. B Lytton, Mr Disraeli, Sir J. Packington, Earl Derby, Lord Stanley, Mr Crossley, and the Bishop of Bath and Wells. I Under all the terrible run of my life I have done for the best.” Whether the wretched man was exhibiting an early version of what we would come to know as The Blackadder Defence – wearing underpants on the head and sticking knitting needles up the nostrils, in the hope that he would be considered totally mad – we shall never know. Forward’s lawyer half-heartedly went for a plea of insanity, but his efforts were ignored.

Whether the wretched man was exhibiting an early version of what we would come to know as The Blackadder Defence – wearing underpants on the head and sticking knitting needles up the nostrils, in the hope that he would be considered totally mad – we shall never know. Forward’s lawyer half-heartedly went for a plea of insanity, but his efforts were ignored.

Arriving at the Gaol just before midday they immediately went to the cell where Forward was held. The executioner was Calcraft who acted as executioner at Stafford and in the “Midland Counties”. The prisoner asked for permission to speak and “exclaimed in an audible voice”, ” I desire to say in the presence of you who are now assembled, and in the presence of Almighty God, into whose immediate presence I am now about to depart, that I die trusting only to the merits of the God-man Jesus Christ”.

Arriving at the Gaol just before midday they immediately went to the cell where Forward was held. The executioner was Calcraft who acted as executioner at Stafford and in the “Midland Counties”. The prisoner asked for permission to speak and “exclaimed in an audible voice”, ” I desire to say in the presence of you who are now assembled, and in the presence of Almighty God, into whose immediate presence I am now about to depart, that I die trusting only to the merits of the God-man Jesus Christ”.