July 1953. Queen Elizabeth was scarcely a month crowned, children were drinking National Health Service orange juice from their Coronation mugs, and Lindsay Hassett’s Australian cricketers, including the legends Richie Benaud, Ray Lindwall and Keith Miller, were preparing for the Third Test at Old Trafford. John Reginald Halliday Christie was sitting in the condemned cell at Pentonville, awaiting the hangman’s noose for multiple murders.

July 1953. Queen Elizabeth was scarcely a month crowned, children were drinking National Health Service orange juice from their Coronation mugs, and Lindsay Hassett’s Australian cricketers, including the legends Richie Benaud, Ray Lindwall and Keith Miller, were preparing for the Third Test at Old Trafford. John Reginald Halliday Christie was sitting in the condemned cell at Pentonville, awaiting the hangman’s noose for multiple murders.

The new Elizabethan age was certainly experienced differently, depending on which part of society you lived in. Most large towns – and all cities – still had pockets of Victorian terraces, tenements and courtyards which would have been familiar to Charles Dickens. Diphtheria, tuberculosis and polio were only in retreat because of the energetic vaccination programme of the relatively new NHS.

A social trend which had the middle-aged and elderly tut-tutting was the rise of the Teddy Boy. So called because their outfits – long coats with velvet collars, tight ‘drainpipe’ trousers and crepe-soled shoes – vaguely harked back to the Edwardian era. In truth, they were more influenced by the fledgling Rock ‘n’ Roll culture which was scandalising America. Every generation has a sub-culture which, at its most harmless is just clothes and hairstyles, but at its worst is just a cover for male violence. Teddy Boys, Mods, Rockers, Chavs, Gangstas – each generation reinvents itself, but each is depressingly the same – a cloak for male testosterone-fuelled rivalry and aggression.

A social trend which had the middle-aged and elderly tut-tutting was the rise of the Teddy Boy. So called because their outfits – long coats with velvet collars, tight ‘drainpipe’ trousers and crepe-soled shoes – vaguely harked back to the Edwardian era. In truth, they were more influenced by the fledgling Rock ‘n’ Roll culture which was scandalising America. Every generation has a sub-culture which, at its most harmless is just clothes and hairstyles, but at its worst is just a cover for male violence. Teddy Boys, Mods, Rockers, Chavs, Gangstas – each generation reinvents itself, but each is depressingly the same – a cloak for male testosterone-fuelled rivalry and aggression.

On the evening of Thursday June 2nd, 1953, the green sward of South London’s Clapham Common was teeming with people – young and old – out to catch the last rays of midsummer sun. There were Teddy Boys from different gangs showing and strutting about in front of their female admirers, but the lads who were sitting on a park bench away from the ‘parade ground’ were not ‘Teds’, nor were they affiliated to any particular gang. The young men sitting on the benches included seventeen year old John Beckley, an apprentice electrical engineer, Frederick Chandler, an eighteen year old bank clerk and Brian Carter.

One of the Teddy Boy gangs was known as The Plough Boys, from their patronage of a local pub, The Plough. Spotting the young men on the benches, and interpreting their different clothing and behaviour as an explicit challenge, members of The Plough Boys decided to provoke Beckley and his friends. A fist fight broke out but Beckley and his mates, realising that they were outnumbered, ran off..

Beckley and Chandler managed to get aboard a number 137 bus, but such was the determination of the Plough Boys to right imagined wrongs that they ran after the bus, and when it stopped for a traffic light, they boarded the bus and dragged Beckley and Chandler out onto the road.

Chandler, despite bleeding from stab wounds to the groin and stomach managed to scramble back on to the open platform of the bus as it was pulling away. John Beckley was not so lucky and became surrounded by the attacking Plough Boys and he was struck repeatedly. He eventually broke away and managed only to run about a hundred yards up the road towards Clapham Old Town.

All of a sudden he stopped and fell against a wall outside an apartment block called Oakeover Manor. He eventually sagged down the wall ending up sitting in a half-sitting position on the pavement, his life literally ebbing away from him.

The remaining Plough Boys, realising that the situation had become more serious than a simple punch-up, ran off. One of the bus passengers, made a call from the Oakeover Manor flatsand another passenger improvised a pillow for the victim with a folded coat. Eventually, at 9.42 pm a policeman arrived and just one hour later, John Beckley was found to have six stab wounds about his body and one to his face. He was pronounced dead at the scene.

The remaining Plough Boys, realising that the situation had become more serious than a simple punch-up, ran off. One of the bus passengers, made a call from the Oakeover Manor flatsand another passenger improvised a pillow for the victim with a folded coat. Eventually, at 9.42 pm a policeman arrived and just one hour later, John Beckley was found to have six stab wounds about his body and one to his face. He was pronounced dead at the scene.

There was no shortage of suspects among the South London gangs. Police swiftly narrowed the field down to six suspects. All were arrested and charged with John Beckley’s murder. Two of the gang denied having been on Clapham Common; two admitted being there, but denied involvement. but all under persistent questioning, later confessed to having taken some part in the attack, though all denied using a knife.

Five youths were initially charged by the Police, with one more charged a few days later, and they were remanded to Bow Street. After a three-day hearing, the case was sent to the Old Bailey for trial. The charged were a 15 year-old shop assistant Ronald Coleman, Terrance Power aged 17 and unemployed, Allan Albert Lawson aged 18 and a carpenter, a labourer Michael John Davies aged 20, Terrence David Woodman, 16, a street-trader and John Fredrick Allan, aged 21, also a labourer.

Michael John Davies, (right) the 20 year old labourer from Clapham, never denied being in the fight. “We all set about two of them on the pavement” he said “I didn’t have a knife, I only used my fists.”

Michael John Davies, (right) the 20 year old labourer from Clapham, never denied being in the fight. “We all set about two of them on the pavement” he said “I didn’t have a knife, I only used my fists.”

On Monday 14th September 1953, at the Old Bailey, Ronald Coleman and Michael John Davies pleaded not guilty to murdering John Beckley. The four others were formally found not guilty after Christmas Humphreys, (left) the prosecutor for the Crown, said he was not satisfied there was any evidence against them on this indictment. However they were charged with common assault and kept in custody.

On Monday 14th September 1953, at the Old Bailey, Ronald Coleman and Michael John Davies pleaded not guilty to murdering John Beckley. The four others were formally found not guilty after Christmas Humphreys, (left) the prosecutor for the Crown, said he was not satisfied there was any evidence against them on this indictment. However they were charged with common assault and kept in custody.

A Daily Mirror headline during the trial simply said Flick Knives, Dance Music and Edwardian Suits.

The trial of Coleman and Davies lasted until the following week when the jury, after considering for three hours forty minutes, said they were unable to agree a verdict.

Mr Humphreys, for the prosecution, said that they did not propose to put Coleman on trial again for murder and a new jury, on the direction of the judge, returned a formal verdict of not guilty. Coleman was charged with common assault along with the four others for which they all received six or nine months in jail.

Michael John Davies’ trial for the murder of John Beckley began on 19th October 1953. Counsel for both the defence, Mr David Weitzman, QC and Mr Christmas Humphreys for the prosecution were the same as for the former trial and the same witnesses appeared.

Having seen the attack from the top deck of the 137 bus, Mary Frayling told the Police that she had seen a particular youth whom she described as the principal attacker put what appeared to be a green handled knife into his right breast pocket. He was wearing a gaudy tie which he removed, putting it in another pocket. She later identified him as John Davies.

How reliable a witness was Mary Frayling? It was late in the evening and her view of the fight on the moving bus with its internal lights on must have been obscured by both the relatively small windows of the bus and the large trees along side the road. In fact Mary Frayling had initially picked out John Davies as the main perpetrator while he was standing in the dock of a local south London court and not in an organised identity parade.

Despite the absence of the knidfe that killed John Beckley, the jury took just two hours to return with a guilty verdict, and Davies was sentenced to death.

Although the actual murder weapon was never found there was a knife that was almost treated as such by Christmas Humphreys and the prosecution during the trial. It was a knife bought by Detective Constable Kenneth Drury in a jewellers near the Plough Inn for three shillings ostensibly as an example of what could have been used by Davies. Incidentally, Drury, (right)  one of the investigating officers in the Beckley murder case, would later become Commander of the Flying Squad in the 1970s and in 1977 was convicted on five counts of corruption and jailed for eight years.

one of the investigating officers in the Beckley murder case, would later become Commander of the Flying Squad in the 1970s and in 1977 was convicted on five counts of corruption and jailed for eight years.

Almost immediately after the guilty verdict there were suspicions to many that there had been a gross miscarriage of justice. Michael John Davies’ case went to appeal and eventually to the House of Lords both to no avail. However after many petitions to the Home Secretary he granted a reprieve for Davies after 92 days in the Condemned Cell. In October 1960 Michael John Davies was released from Wandsworth Prison after seven years, although not officially pardoned, he was now a free man.

The killing of John Beckley had a chilling resonance many years later with another notorious stabbing, the murder of Stephen Lawrence. Once again, there would be attack by a gang of young men. Once again, a knife would be the weapon, but would never be found. Once again it would be very much open to doubt as to who struck the fatal blow. Although Stephen’s death was due to a racist attack, the killing of John Beckley was equally tribal – a young life taken because he was different.

When we next meet Charles it is 1964, and much has changed. The streets of the old East End, having been substantially rearranged by Hitler’s bombs, have been redeveloped. More significantly, the Jewish people have largely moved on. Many families have prospered and they have moved out to the comfortable suburbs. Charles Horowitz has also prospered, after a fashion. His chosen career is Law, and in order to rise through the ranks of the socially and ethnically tightly knit Inns of Court, he has abandoned Horowitz and reinvented himself as Charles Holborne.

When we next meet Charles it is 1964, and much has changed. The streets of the old East End, having been substantially rearranged by Hitler’s bombs, have been redeveloped. More significantly, the Jewish people have largely moved on. Many families have prospered and they have moved out to the comfortable suburbs. Charles Horowitz has also prospered, after a fashion. His chosen career is Law, and in order to rise through the ranks of the socially and ethnically tightly knit Inns of Court, he has abandoned Horowitz and reinvented himself as Charles Holborne. for those who want to complete the picture, but with The Lighterman it is sufficient to say that Charles has made a very undesirable enemy. It is probably merely an exercise in semantics to distinguish between the equally awful twin sons of Charles David Kray and Violet Annie Lee, but most casual observers agree that Ronnie was the worst of two evils. The homosexual, paranoid and pathologically violent gangster has a list of people who have upset him. The first name on that list is none other than Charles Holborne aka Horowitz, and the brutal East End hoodlum is determined that Charles must be done away with.

for those who want to complete the picture, but with The Lighterman it is sufficient to say that Charles has made a very undesirable enemy. It is probably merely an exercise in semantics to distinguish between the equally awful twin sons of Charles David Kray and Violet Annie Lee, but most casual observers agree that Ronnie was the worst of two evils. The homosexual, paranoid and pathologically violent gangster has a list of people who have upset him. The first name on that list is none other than Charles Holborne aka Horowitz, and the brutal East End hoodlum is determined that Charles must be done away with. Simon Michael (left) combines an encyclopaedic knowledge of London, with an insider’s grasp of courtroom proceedings. I cannot say if it was the author’s intention – only he can concur or disagree – but his writing left me with a profound sense of sadness over what London’s riverside and its East End once were – and what they have become. This is a beautifully written novel which succeeds on three different levels. Firstly, it is a superb recreation of a London which is just a lifetime away, but may as well be the Egypt of the pharaohs, such is its distance from us. Secondly, it is a tense and authentic legal thriller, with all the nuances and delicate sensibilities of the British legal system pushed into the spotlight. Thirdly – and perhaps most importantly – we meet characters who are totally convincing, speak in a manner which sounds authentic, and have all the qualities and flaws which we recognise in people of our own acquaintance. The Lighterman is published by Urbane Publications and is available here.

Simon Michael (left) combines an encyclopaedic knowledge of London, with an insider’s grasp of courtroom proceedings. I cannot say if it was the author’s intention – only he can concur or disagree – but his writing left me with a profound sense of sadness over what London’s riverside and its East End once were – and what they have become. This is a beautifully written novel which succeeds on three different levels. Firstly, it is a superb recreation of a London which is just a lifetime away, but may as well be the Egypt of the pharaohs, such is its distance from us. Secondly, it is a tense and authentic legal thriller, with all the nuances and delicate sensibilities of the British legal system pushed into the spotlight. Thirdly – and perhaps most importantly – we meet characters who are totally convincing, speak in a manner which sounds authentic, and have all the qualities and flaws which we recognise in people of our own acquaintance. The Lighterman is published by Urbane Publications and is available here.

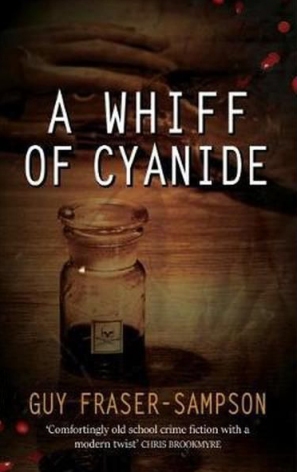

Readers of the two previous books in the Hampstead Murders series, Death In Profile and Miss Christie Regrets, will know what to expect, but for readers new to the novels here is a Bluffers’ Guide. The stories are set in modern day Hampstead, a very select and expensive district of London. The police officers involved are, principally, Detective Superintendent Simon Collison, a civilised and gentlemanly type who, despite his charm and urbanity, is reluctant to climb the promotion ladder which is presented to him. Detective Sergeant Karen Willis is, likewise, of finishing school material, but also a very good copper with – as we are often reminded – legs to die for. She is in love, but not exclusively, with Detective Inspector Bob Metcalfe, a decent sort with a heart of gold. If he were operating back in the Bulldog Drummond era he would certainly have a lantern jaw and blue eyes that could be steely, or twinkle with kindness as circumstances dictate.

Readers of the two previous books in the Hampstead Murders series, Death In Profile and Miss Christie Regrets, will know what to expect, but for readers new to the novels here is a Bluffers’ Guide. The stories are set in modern day Hampstead, a very select and expensive district of London. The police officers involved are, principally, Detective Superintendent Simon Collison, a civilised and gentlemanly type who, despite his charm and urbanity, is reluctant to climb the promotion ladder which is presented to him. Detective Sergeant Karen Willis is, likewise, of finishing school material, but also a very good copper with – as we are often reminded – legs to die for. She is in love, but not exclusively, with Detective Inspector Bob Metcalfe, a decent sort with a heart of gold. If he were operating back in the Bulldog Drummond era he would certainly have a lantern jaw and blue eyes that could be steely, or twinkle with kindness as circumstances dictate. Collison, Metcalfe, Willis and Collins have an ever lengthening list of questions to be answered. Why was Ann Durham brandishing a bottle of cyanide as she presided over one of the convention panels? Who actually wrote her most popular – and best selling – series of novels? Fraser-Sampson (right) spins a beautiful yarn here, with regular nods to The Golden Age during a convincing account of modern police procedure. Not only is the crime eventually solved, but he provides us with a delightful solution to the Willis – Metcalfe – Collins love triangle.

Collison, Metcalfe, Willis and Collins have an ever lengthening list of questions to be answered. Why was Ann Durham brandishing a bottle of cyanide as she presided over one of the convention panels? Who actually wrote her most popular – and best selling – series of novels? Fraser-Sampson (right) spins a beautiful yarn here, with regular nods to The Golden Age during a convincing account of modern police procedure. Not only is the crime eventually solved, but he provides us with a delightful solution to the Willis – Metcalfe – Collins love triangle.

Now, Thorne becomes involved in another kind of hell on earth, and one where all absent devils have been called home, all leave cancelled, and any recently retired fallen angels pressed back into duty. The fires stoked in this particular hellish pit illuminate the ghastly world inhabited by some British Asian communities who sanction murder in the name of their warped concept of family honour. Among the ghosts which inhabit the darker parts of Thorne’s memory is that of Meena Athwal. She was killed, he is certain, at the behest of her family, but her death remains unavenged in a court of justice.

Now, Thorne becomes involved in another kind of hell on earth, and one where all absent devils have been called home, all leave cancelled, and any recently retired fallen angels pressed back into duty. The fires stoked in this particular hellish pit illuminate the ghastly world inhabited by some British Asian communities who sanction murder in the name of their warped concept of family honour. Among the ghosts which inhabit the darker parts of Thorne’s memory is that of Meena Athwal. She was killed, he is certain, at the behest of her family, but her death remains unavenged in a court of justice.

The Urban Dictionary tells me that a “keeper” is

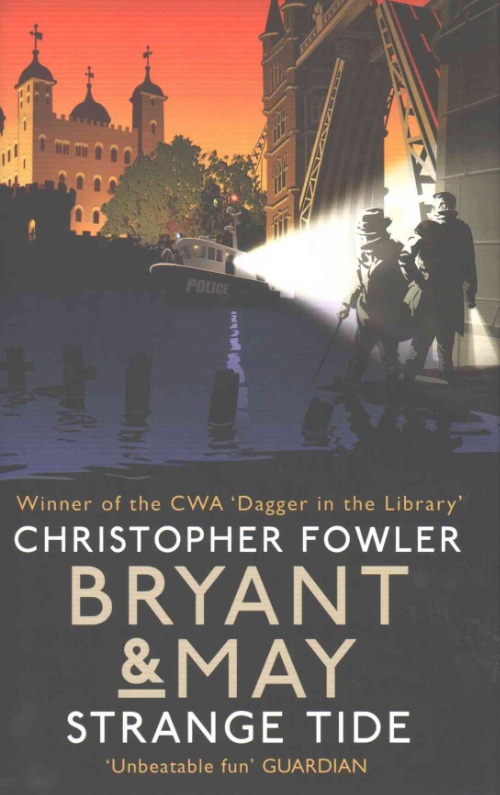

The Urban Dictionary tells me that a “keeper” is  STRANGE TIDE is set, as you may expect, in London, but it’s a London few of us will ever see. It’s a world of forgotten alleyways, strange histories, abandoned amusement arcades, inexplicable legends and murder – always murder. Strange Tide was my book of the year for 2016, and you can read my review of it by following

STRANGE TIDE is set, as you may expect, in London, but it’s a London few of us will ever see. It’s a world of forgotten alleyways, strange histories, abandoned amusement arcades, inexplicable legends and murder – always murder. Strange Tide was my book of the year for 2016, and you can read my review of it by following

Barbara Nadel (left) has created one of the more adventurous pairings in recent private eye fiction. The pair return for another episode set in the modern East End of London. Lee Arnold is a former soldier and policeman but now he is the proprietor of an investigation agency, partnered by a young Anglo Bengali widow, Mumtaz Hakim. Abbas al’Barri was an interpreter back in the first Gulf War, where he became close friends with Arnold. He escaped from Iraq with his family, and settled in London, but now he has a huge problem for which he requires the services of Arnold and Hakim. Fayyad – Abbas’s son – has become radicalised and gone to wage jihad in Syria. After receiving a mysterious package containing a significant religious artifact, Abbas and his wife are convinced that it represents a cry for help from Fayyad who, they believe, is desperate to return home.

Barbara Nadel (left) has created one of the more adventurous pairings in recent private eye fiction. The pair return for another episode set in the modern East End of London. Lee Arnold is a former soldier and policeman but now he is the proprietor of an investigation agency, partnered by a young Anglo Bengali widow, Mumtaz Hakim. Abbas al’Barri was an interpreter back in the first Gulf War, where he became close friends with Arnold. He escaped from Iraq with his family, and settled in London, but now he has a huge problem for which he requires the services of Arnold and Hakim. Fayyad – Abbas’s son – has become radicalised and gone to wage jihad in Syria. After receiving a mysterious package containing a significant religious artifact, Abbas and his wife are convinced that it represents a cry for help from Fayyad who, they believe, is desperate to return home. Their plan, it must be said, is fraught with danger and is almost bound to go pear-shaped, but within the confines of crime fiction thrillers, makes for a nail-biting narrative. What could possibly go wrong with Hakim befriending Abu Imad on Facebook and pretending to be a starstruck Muslim lass called Mishal who would like nothing better than to travel out to Syria to be at her hero’s side? Facebook leads to Skype, and with the help of make-up and a head covering, ‘Mishal’ arranges to travel to Amsterdam, complete with Abu Imad’s shopping list from Harrods. As you might expect, everything then goes wrong, in bloody and spectacular fashion.

Their plan, it must be said, is fraught with danger and is almost bound to go pear-shaped, but within the confines of crime fiction thrillers, makes for a nail-biting narrative. What could possibly go wrong with Hakim befriending Abu Imad on Facebook and pretending to be a starstruck Muslim lass called Mishal who would like nothing better than to travel out to Syria to be at her hero’s side? Facebook leads to Skype, and with the help of make-up and a head covering, ‘Mishal’ arranges to travel to Amsterdam, complete with Abu Imad’s shopping list from Harrods. As you might expect, everything then goes wrong, in bloody and spectacular fashion.

His London copper, DC Max Wolfe, becomes involved when a refrigerated lorry is abandoned on a street in London’s Chinatown. The emergency services breathe a huge sigh of relief when they discover that the truck is not carrying a bomb, but their relaxed mood is short-lived when they break open the doors to discover that the vehicle contains the frozen bodies of twelve young women. The bundle of passports – mostly fake – found in the lorry’s cab poses an instant conundrum. There are thirteen passports, but only twelve girls. Who – and where – is the missing person?

His London copper, DC Max Wolfe, becomes involved when a refrigerated lorry is abandoned on a street in London’s Chinatown. The emergency services breathe a huge sigh of relief when they discover that the truck is not carrying a bomb, but their relaxed mood is short-lived when they break open the doors to discover that the vehicle contains the frozen bodies of twelve young women. The bundle of passports – mostly fake – found in the lorry’s cab poses an instant conundrum. There are thirteen passports, but only twelve girls. Who – and where – is the missing person? Max Wolfe certainly gets around for a humble Detective Constable, but he is an engaging character and his home background of the Smithfield flat, young daughter, motherly Irish childminder and adorable pooch make a welcome change from the usual domestic arrangements of fictional London coppers with their neglected wives, alcohol dependency and general misanthropy. Parsons (right) is clearly angry about many aspects of modern life in Britain, but he is too good to allow his writing to descend into mere polemic. Instead, he uses his passion to drive the narrative and lend credibility to the way his characters behave.

Max Wolfe certainly gets around for a humble Detective Constable, but he is an engaging character and his home background of the Smithfield flat, young daughter, motherly Irish childminder and adorable pooch make a welcome change from the usual domestic arrangements of fictional London coppers with their neglected wives, alcohol dependency and general misanthropy. Parsons (right) is clearly angry about many aspects of modern life in Britain, but he is too good to allow his writing to descend into mere polemic. Instead, he uses his passion to drive the narrative and lend credibility to the way his characters behave.

July 1953. Queen Elizabeth was scarcely a month crowned, children were drinking National Health Service orange juice from their Coronation mugs, and Lindsay Hassett’s Australian cricketers, including the legends Richie Benaud, Ray Lindwall and Keith Miller, were preparing for the Third Test at Old Trafford. John Reginald Halliday Christie was sitting in the condemned cell at Pentonville, awaiting the hangman’s noose for multiple murders.

July 1953. Queen Elizabeth was scarcely a month crowned, children were drinking National Health Service orange juice from their Coronation mugs, and Lindsay Hassett’s Australian cricketers, including the legends Richie Benaud, Ray Lindwall and Keith Miller, were preparing for the Third Test at Old Trafford. John Reginald Halliday Christie was sitting in the condemned cell at Pentonville, awaiting the hangman’s noose for multiple murders. A social trend which had the middle-aged and elderly tut-tutting was the rise of the Teddy Boy. So called because their outfits – long coats with velvet collars, tight ‘drainpipe’ trousers and crepe-soled shoes – vaguely harked back to the Edwardian era. In truth, they were more influenced by the fledgling Rock ‘n’ Roll culture which was scandalising America. Every generation has a sub-culture which, at its most harmless is just clothes and hairstyles, but at its worst is just a cover for male violence. Teddy Boys, Mods, Rockers, Chavs, Gangstas – each generation reinvents itself, but each is depressingly the same – a cloak for male testosterone-fuelled rivalry and aggression.

A social trend which had the middle-aged and elderly tut-tutting was the rise of the Teddy Boy. So called because their outfits – long coats with velvet collars, tight ‘drainpipe’ trousers and crepe-soled shoes – vaguely harked back to the Edwardian era. In truth, they were more influenced by the fledgling Rock ‘n’ Roll culture which was scandalising America. Every generation has a sub-culture which, at its most harmless is just clothes and hairstyles, but at its worst is just a cover for male violence. Teddy Boys, Mods, Rockers, Chavs, Gangstas – each generation reinvents itself, but each is depressingly the same – a cloak for male testosterone-fuelled rivalry and aggression.

The remaining Plough Boys, realising that the situation had become more serious than a simple punch-up, ran off. One of the bus passengers, made a call from the Oakeover Manor flatsand another passenger improvised a pillow for the victim with a folded coat. Eventually, at 9.42 pm a policeman arrived and just one hour later, John Beckley was found to have six stab wounds about his body and one to his face. He was pronounced dead at the scene.

The remaining Plough Boys, realising that the situation had become more serious than a simple punch-up, ran off. One of the bus passengers, made a call from the Oakeover Manor flatsand another passenger improvised a pillow for the victim with a folded coat. Eventually, at 9.42 pm a policeman arrived and just one hour later, John Beckley was found to have six stab wounds about his body and one to his face. He was pronounced dead at the scene.

Michael John Davies, (right) the 20 year old labourer from Clapham, never denied being in the fight. “We all set about two of them on the pavement” he said “I didn’t have a knife, I only used my fists.”

Michael John Davies, (right) the 20 year old labourer from Clapham, never denied being in the fight. “We all set about two of them on the pavement” he said “I didn’t have a knife, I only used my fists.” On Monday 14th September 1953, at the Old Bailey, Ronald Coleman and Michael John Davies pleaded not guilty to murdering John Beckley. The four others were formally found not guilty after Christmas Humphreys, (left) the prosecutor for the Crown, said he was not satisfied there was any evidence against them on this indictment. However they were charged with common assault and kept in custody.

On Monday 14th September 1953, at the Old Bailey, Ronald Coleman and Michael John Davies pleaded not guilty to murdering John Beckley. The four others were formally found not guilty after Christmas Humphreys, (left) the prosecutor for the Crown, said he was not satisfied there was any evidence against them on this indictment. However they were charged with common assault and kept in custody.

one of the investigating officers in

one of the investigating officers in

Other murders follow, and each has been committed in one of the parks and gardens – the Wild Chambers – which are scattered throughout central London. Are the gardens linked, like some erratically plotted ley line? Why are the murders connected to a tragic freak accident in a road tunnel near London Bridge? Why are the murder sites speckled with tiny balls of lead?

Other murders follow, and each has been committed in one of the parks and gardens – the Wild Chambers – which are scattered throughout central London. Are the gardens linked, like some erratically plotted ley line? Why are the murders connected to a tragic freak accident in a road tunnel near London Bridge? Why are the murder sites speckled with tiny balls of lead? Along the way, Fowler (right) has the eagle eye of John Betjeman in the way that he recognises the potency of ostensibly insignificant brand names and the way that they can instantly recreate a period of history, or a passing social mood. At one point, Bryant tries to pay for a round of drinks in a pub:

Along the way, Fowler (right) has the eagle eye of John Betjeman in the way that he recognises the potency of ostensibly insignificant brand names and the way that they can instantly recreate a period of history, or a passing social mood. At one point, Bryant tries to pay for a round of drinks in a pub:

In 1997, at the long-delayed inquest into the murder, the five men suspected of the killing refused to co-operate and maintained strict silence. Despite direction to the contrary by the Coroner, the jury returned the verdict that Stephen Lawrence was killed “in a completely unprovoked racist attack by five white youths.” Later that year, The Daily Mail named the five as Stephen’s killers, and invited them to sue for defamation. Needless to say, none of the five took up the challenge. Below, the five suspects run the gauntlet of a furious crowd after the inquest.

In 1997, at the long-delayed inquest into the murder, the five men suspected of the killing refused to co-operate and maintained strict silence. Despite direction to the contrary by the Coroner, the jury returned the verdict that Stephen Lawrence was killed “in a completely unprovoked racist attack by five white youths.” Later that year, The Daily Mail named the five as Stephen’s killers, and invited them to sue for defamation. Needless to say, none of the five took up the challenge. Below, the five suspects run the gauntlet of a furious crowd after the inquest.