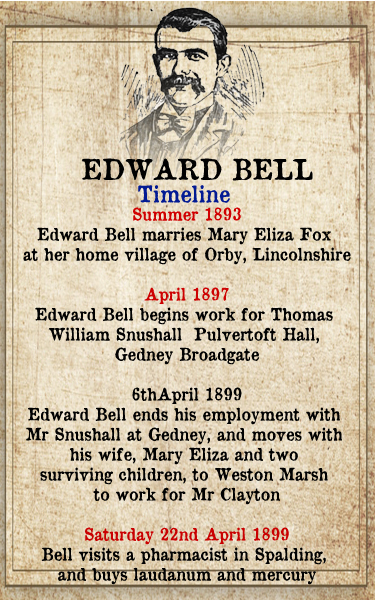

Spring 1899. Edward Bell, farm labourer of Weston Marsh, Spalding, is dissatisfied with his wife Mary Eliza, who has borne him six children in six years, and is determined to get her out of the way so that he can pursue a passion for a younger woman. Mary Hodson. He has bought poison from a chemist in Spalding. He has also bought a soda siphon. Over the weekend of 23rd/24th April he begins to administer the poison to his wife, mixed with the soda, saying that it is a tonic which will calm stomach problems from which she regularly suffers.

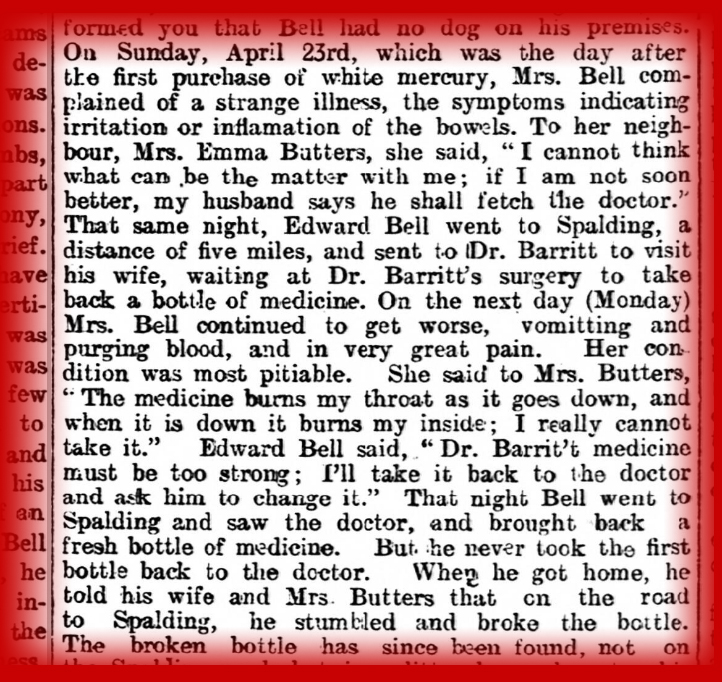

On Monday 24th April, Mary Eliza Bell begins to suffer agonising symptoms. Her mother is summoned from Orby to be at her side, and Edward Bell fetches the doctor, who diagnoses inflammation of the bowels. Over the next two days, Bell attempts to buy more poison and completely pulls the wool over the eyes of both the doctor and the chemist. What happened next is best described in the words of various astonishing reports in newspaper later in the case when Bell’s crime had been unmasked. These are from the Sheffield and Rotherham Independent:

Bell’s behaviour might appal the reader over a century after his dreadful crime, but what he did next is little short of unbelievable. After watching his wife die in the extremes of agony, he calmly walked into Spalding again, knocked on Dr Barritt’s door, informed him that his wife had died, and asked for a death certificate, which the medical man duly wrote out, citing the cause of death as the bowel condition for which he believed he had been treating her. Wasting no time, Bell then organised the removal of his wife’s corpse to her home village of Orby. She left the family cottage in a cart, and her remains were conveyed by railway for the remainder of the journey.

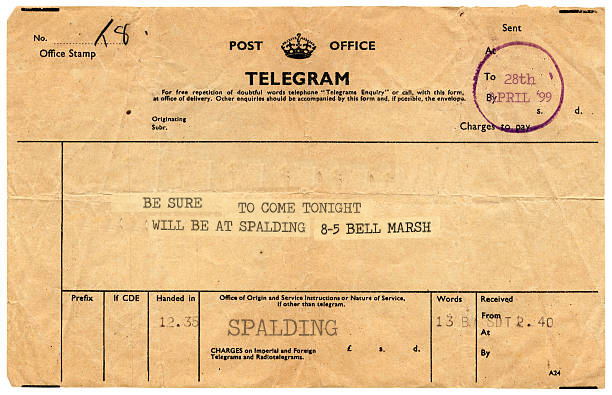

Mary Eliza Bell’s funeral was scheduled for Saturday 28th April, and Edward Bell left left Spalding on an early train to play the part of the grieving husband, but not before finding time to send this telegram (facsimile below) to “Miss Hodson, Rectory, Barton-le-Cley”

Bell’s arrogance- or stupidity – is barely credible. And yet, and yet. He had already hoodwinked his wife, the local doctor, a Spalding pharmacist, so it is only to be supposed that he thought he was on a winning streak. What happened next was to show that Bell’s trust in the gullibility of both the law – and ordinary people – was misplaced.

NEXT – An anonymous letter,

the final indignity inflicted upon Mary Eliza Bell,

and, in the end, justice is served.