Mary Ann Elizabeth Witrick (or Witterick) was born in Wereham, Norfolk in 1857. Her baptism (above) is recorded in the village church (below) as taking place in 1859. Her parents, John and Ann (née Rust) were poor, hard-working and, like so many other families across the land, produced children on a regular basis. There was no contraception other than abstinence, and child mortality tended to keep a lid on the birth-rate.

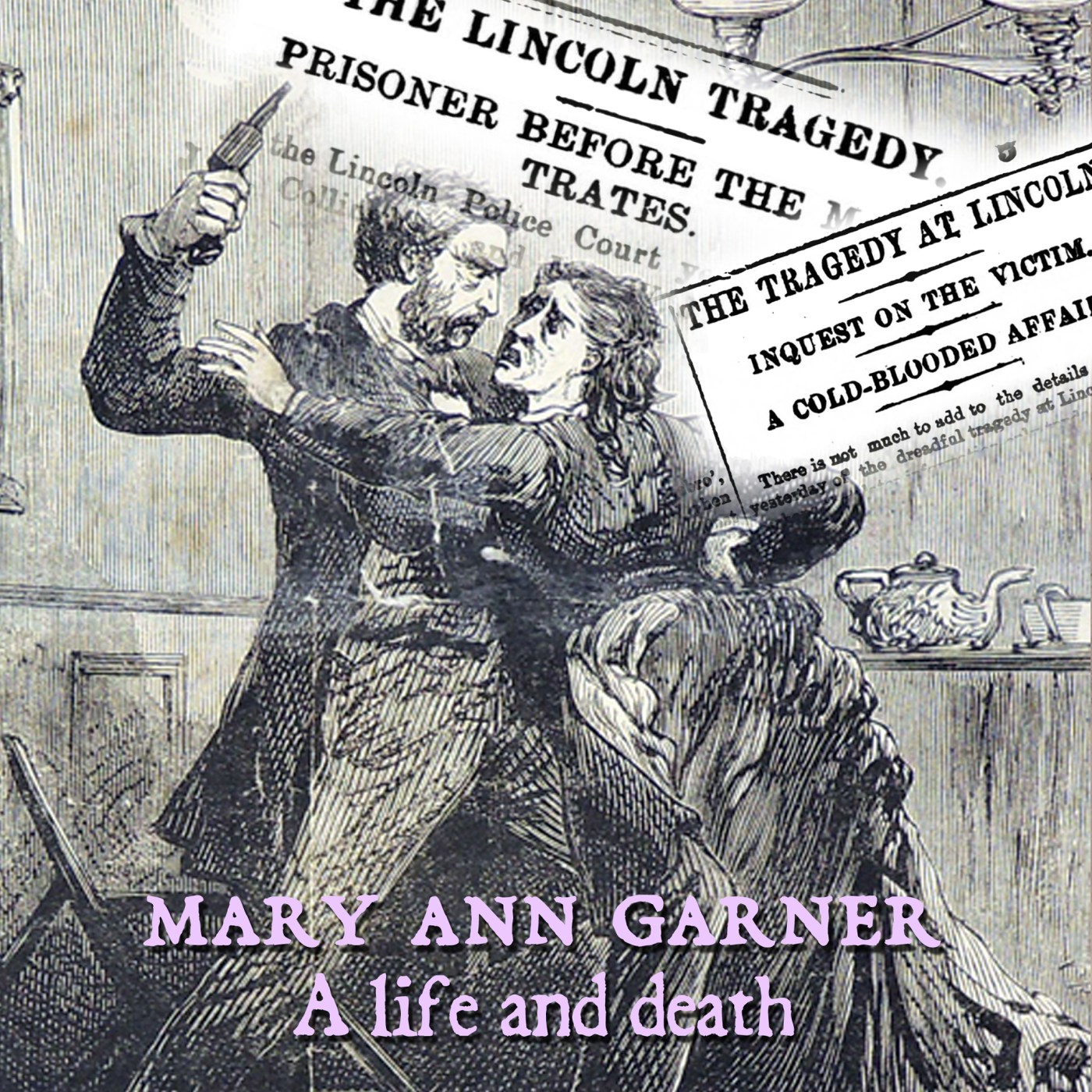

Her life was to end, violently, in a Lincoln terraced house on the evening of 31st March 1891. We know that the family were still in Wereham in 1861, but the remainder of her youth – and where she spent it – remains something of a mystery. We do know that in 1880, she married a Lincoln widower, Henry Garner. Garner’s wife Charlotte (née Foster) had died in 1879. They had one son, John Henry, who had been born on 23rd April 1875. Mary Ann and Henry went on to have three children, Arthur Garner (b1882) Ernest Witterick Garner (b1883) and Ada Florence Garner (b1886).

What was to be a run of misfortune for Mary Ann Garner began in 1889, with the death of her husband. He died on 19th August 1889, in Lincoln Lunatic Asylum, Bracebridge (above). ‘Bracebridge’ was a potent word in Lincolnshire, certainly when I was growing up. I spent many hours being looked after by my grandmother in Louth, and when I played her up (which was frequently) she didn’t mince her words. “You’ll have me in Bracebridge, you little bugger!”

Henry Garner had just turned 40. I can only speculate on his cause of death. One possibility might be, given his age, was what was euphemised as GPI (General Paralysis of the Insane) or Paresis. When researching family history one has to be prepared for unpleasant surprises, as was the case with my great grandfather. He died in an asylum, of Paresis. It is actually the final and fatal stages of syphilis. The disease could be contracted when young, but then the visible symptoms would disappear, only for the disease to return later in life, manifesting itself as delusions of grandeur, erratic behaviour, brain inflammation and, finally, death.

It is unlikely that Henry Garner left his widow very much by way of an inheritance. The early spring of 1891 found her in a tiny end-of-terrace, 19 Stanley Place, pictured below as it is now. To make ends meet, she was taking in washing and, according to a newspaper report, was also taking in lodgers. This is scarcely credible from a modern viewpoint, looking at the size of the house, but that was a very different time in terms of privacy and living space.

At some point after the death of her husband, Mary Ann met a young man called Arthur Spencer. He was ten years her junior and came originally from Blyth in Nottinghamshire. His trade was pork butcher. For a time, he lodged at 19 Stanley Place, and one must assume that he shared Mary Ann’s bed. He asked her to marry him, but she refused, saying they were better off apart. After this, he left the house, and went back to live over the shop where he worked. Spencer was clearly besotted with Mary Ann, and on the evening of Sunday 29th March, he returned to Stanley Place and told her that if she wouldn’t marry him, he would shoot her and then turn the gun on himself. Mary Ann did not take him seriously, and sent him packing. The following evening, 30th March, Spencer came again to see Mary Ann. A newspaper reported, rather cryptically:

“They appear to have gone upstairs together, leaving the eldest child, a boy of 14, in the kitchen, the other children being in bed.”

What happened next was to send a shudder or revulsion through both the citizens of Lincoln, and cities, towns and villages across the land.

IN PART TWO

Gunshots

Trial and retribution

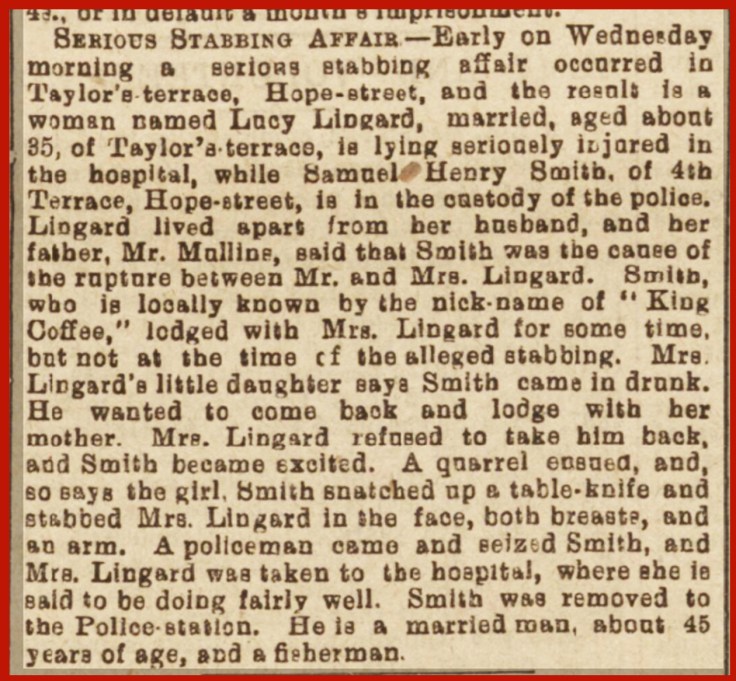

The report was overly optimistic. Lucy Lingard hovered between life and death for a while, but on the Sunday, four days after the attack, she died of her injuries, described below at the subsequent inquest.

The report was overly optimistic. Lucy Lingard hovered between life and death for a while, but on the Sunday, four days after the attack, she died of her injuries, described below at the subsequent inquest.

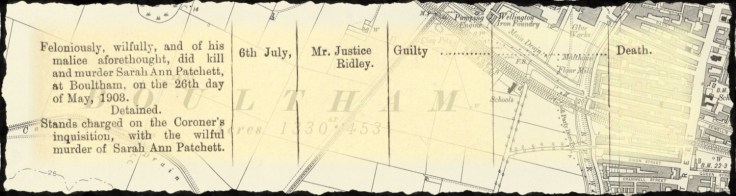

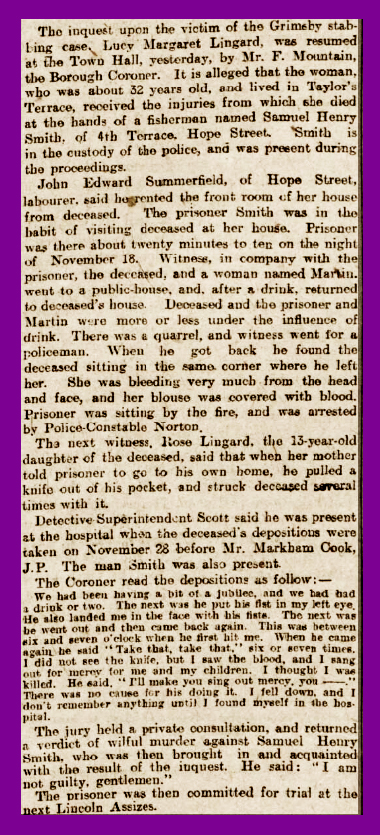

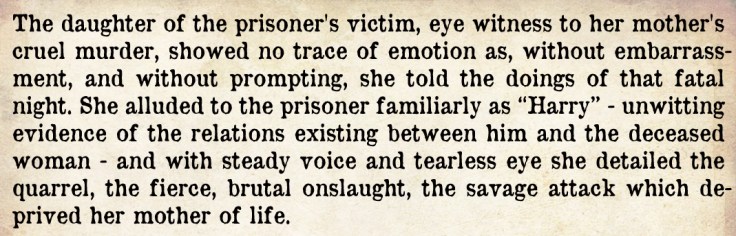

Inevitably, the Coroner’s court, convened at the beginning of December, declared Smith to be guilty of murder, and now it would be up to the Lincoln Assizes court, Judge and Jury, to determine his fate. Smith spent the rest of December – including Christmas – and the greater part of February in Lincoln gaol. On Wednesday 25th February 1903, before Mr Justice Kennedy (right), Samuel Henry Smith ‘had his hour in court’. Despite the suggestion to the jury that the charge should be reduced to one of manslaughter, it all went badly for Smith.

Inevitably, the Coroner’s court, convened at the beginning of December, declared Smith to be guilty of murder, and now it would be up to the Lincoln Assizes court, Judge and Jury, to determine his fate. Smith spent the rest of December – including Christmas – and the greater part of February in Lincoln gaol. On Wednesday 25th February 1903, before Mr Justice Kennedy (right), Samuel Henry Smith ‘had his hour in court’. Despite the suggestion to the jury that the charge should be reduced to one of manslaughter, it all went badly for Smith.

Hope Street in Grimsby was cleared of its terraces in the late 1960s (pictured above, thanks to Hope Street History), but a late 19th century map shows back-to-back houses opening directly onto the street, and every so often there would courtyards, each open area being surrounded on three sides by further dwellings. For those interested in the history of Hope Street, there is a Facebook page that gives access to an excellent pdf document describing the history of the street. That link is

Hope Street in Grimsby was cleared of its terraces in the late 1960s (pictured above, thanks to Hope Street History), but a late 19th century map shows back-to-back houses opening directly onto the street, and every so often there would courtyards, each open area being surrounded on three sides by further dwellings. For those interested in the history of Hope Street, there is a Facebook page that gives access to an excellent pdf document describing the history of the street. That link is

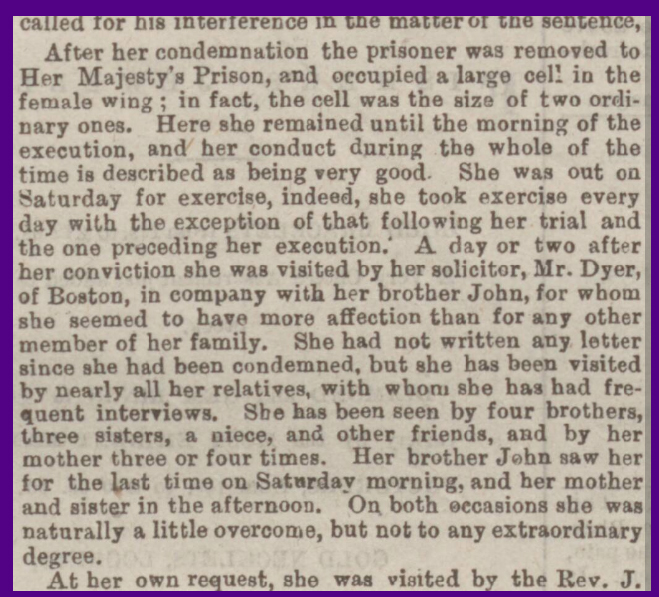

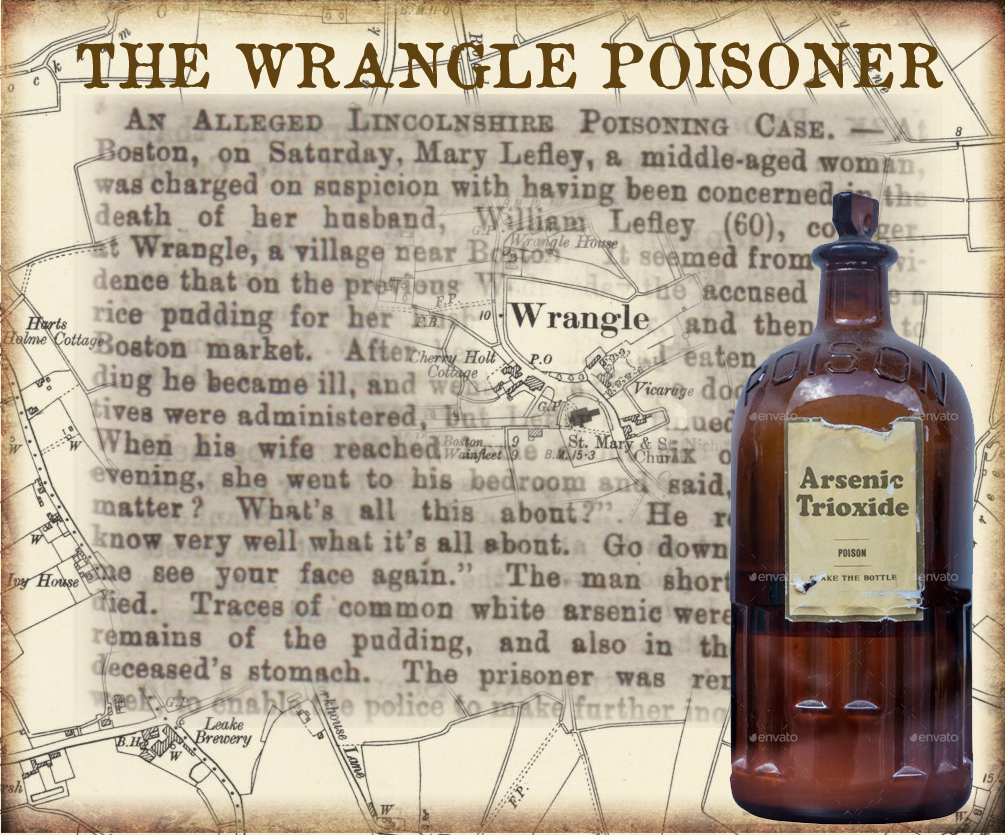

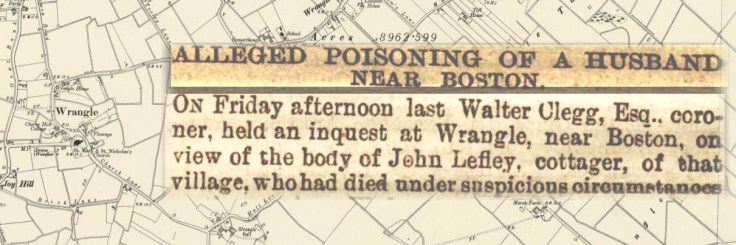

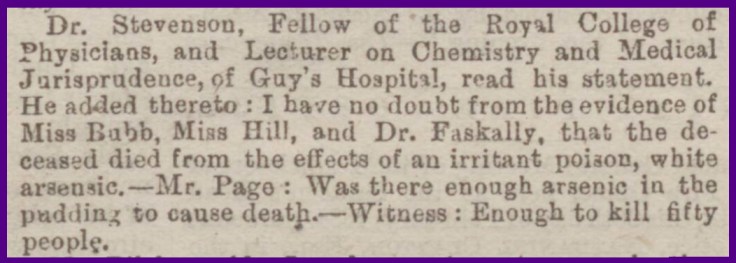

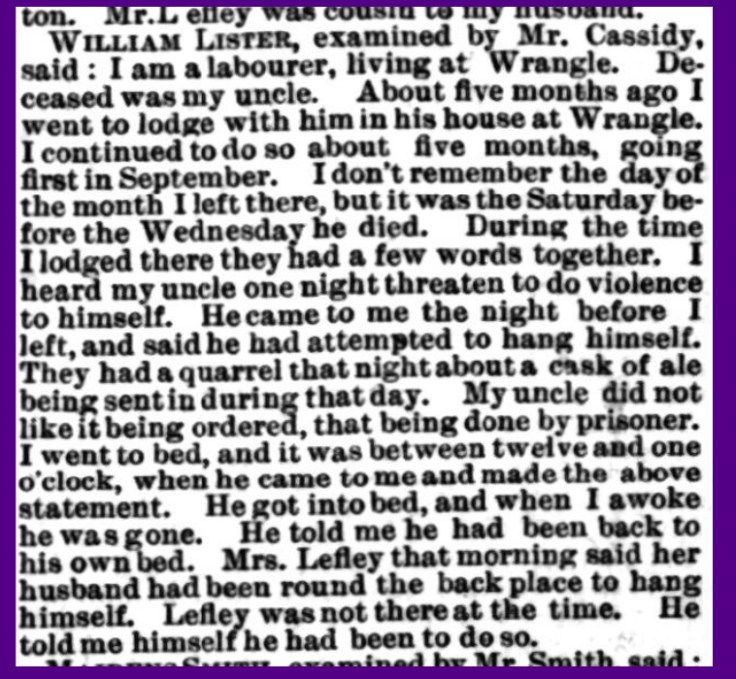

Based mainly on the question, “Who else could have done it?” Mary Lefley was sent for trial at the Lincoln Assizes. She was to appear before Mr Justice North. Mary’s defence barrister made the point:

Based mainly on the question, “Who else could have done it?” Mary Lefley was sent for trial at the Lincoln Assizes. She was to appear before Mr Justice North. Mary’s defence barrister made the point: