“And the guardians and their ladies,

Although the wind is east,

Have come in their furs and wrappers,

To watch their charges feast;

To smile and be condescending,

Put pudding on pauper plates.

To be hosts at the workhouse banquet

They’ve paid for — with the rates.”

Verse two of the celebrated – and often parodied – ballad poem by the Victorian campaigning journalist George R Sims, In The Workhouse, Christmas Day. Most of us older folk know the poem and its melancholy message. An old man is sitting down to his Christmas dinner in the workhouse, but one memory is too much for him, and he angrily relates the tale of his late wife, who was forced to die of hunger on the streets because of the harshness of the workhouse regulations. The relevance of this to Chris Nickson’s The Tin God lies in the first line of the verse above, because the heroine of the story is the wife of Leeds copper Tom Harper, and she is standing for election to the workhouse Board of Guardians.

So? This Leeds in October 1897, and women simply did not stand for office of any kind, and when Annabelle Harper, along with several colleagues from the fledgling Suffrage movement decide to enter the election, it is a controversial decision, because the concept of women migrating from their proper places, be they the bedroom, the withdrawing room or the kitchen, is anathema to most of the ‘gentlemen’ in Leeds society.

Outraged leading articles appear in local newspapers, but someone believes that the sword – or something equally violent – is mightier than the pen, and a homemade bomb destroys a church hall just before Annabelle Harper is due to speak to her supporters. The caretaker is tragically killed by the explosion, and matters go from bad to worse when more bombs are found, and several of the women candidates are threatened.

Outraged leading articles appear in local newspapers, but someone believes that the sword – or something equally violent – is mightier than the pen, and a homemade bomb destroys a church hall just before Annabelle Harper is due to speak to her supporters. The caretaker is tragically killed by the explosion, and matters go from bad to worse when more bombs are found, and several of the women candidates are threatened.

Superintendent Tom Harper is already involved in investigating the criminal aspects of the case, but when the husband of one of the women is murdered while sitting at his own kitchen table, the affair becomes a hunt for a murderer. The killer leaves a few tantalising clues, and Harper becomes conflicted between devoting every hour that God sends to tracking down the killer – and keeping his wife from becoming the next victim.

Nickson drops us straight onto the streets of his beloved Leeds. We smell the stench of the factories, hear the clatter of iron-shod hooves on the cobbles, curse when the soot from the chimneys blackens the garments on our washing lines and – most tellingly – we feel the pangs of hunger gnawing at the bellies of the impoverished. We have an intriguing sub-plot involving a smuggling gang importing illegal spirits into Leeds, authentic dialogue, matchless historical background and, best of all, a few hours under the spell of one of the best story tellers in modern fiction.

You want more? Well, it’s there. Nickson is a fine musician and a distinguished music journalist, and he cunningly works into the plot one of the more notable musical names associated with Leeds and West Yorkshire, the folksong collector Frank Kidson (above). The killer shares Kidson’s passion for the old songs – if not his humanity and feelings for his fellow human beings – and he leaves handwritten fragments of English songs at the scenes of his attacks.

The Tin God is published by Severn House and is available now. It will be obvious that I am a great admirer of Chris Nickson’s writing, and if you click the images below, you can read the reviews for some of his other excellent novels.

I have become a huge admirer of the writing of Chris Nickson (left) . He says on his website:

I have become a huge admirer of the writing of Chris Nickson (left) . He says on his website: You will be pushed to find better opening words to a novel even were you to search all year:

You will be pushed to find better opening words to a novel even were you to search all year:

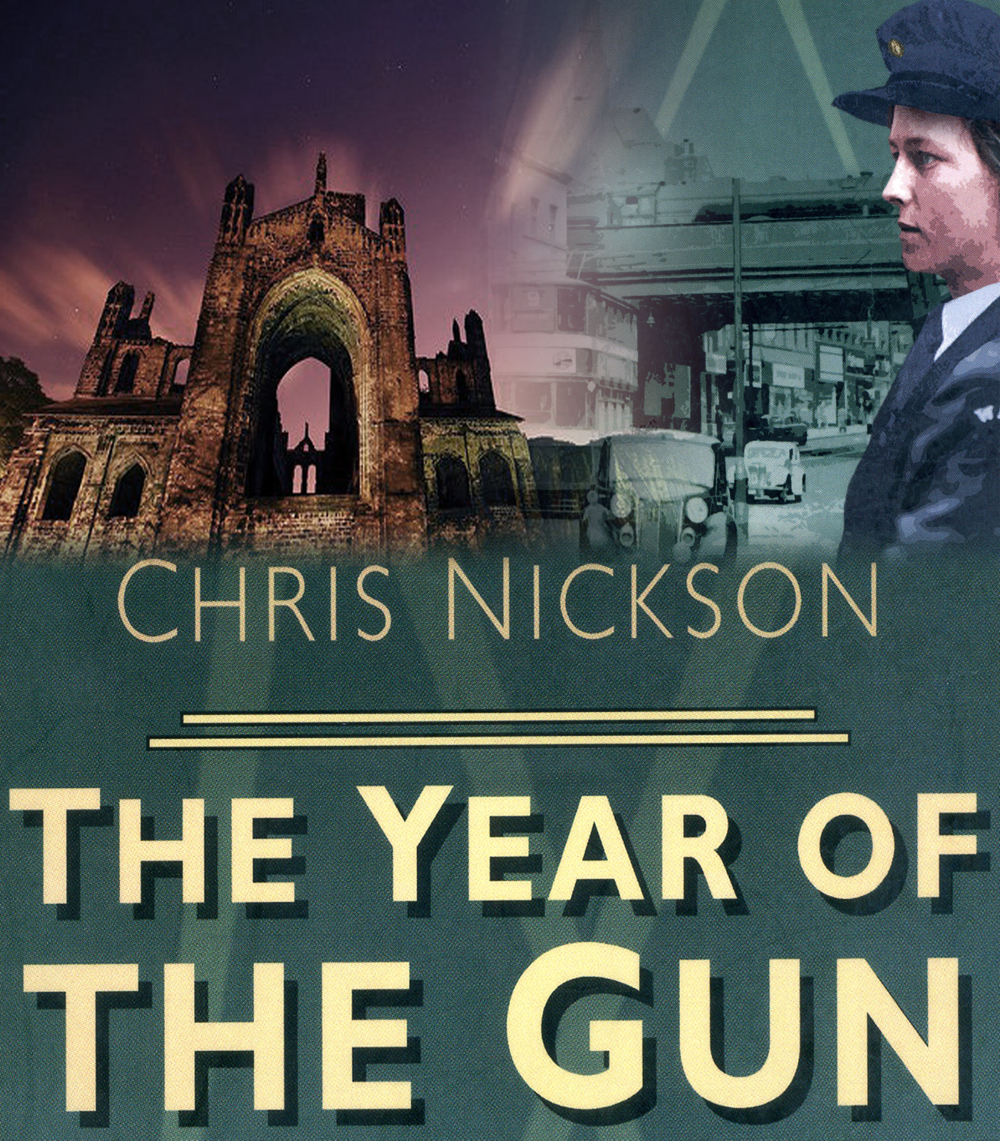

So, Lottie is back in uniform again, but this time as a lowly member of the Women’s Auxiliary Police Corps. Her main job is to drive her boss, Detective Superintendent McMillan, to wherever he needs to go. McMillan, a veteran of The Great War, certainly needs his transport as a killer seems to be stalking vulnerable young women across the city. Kate Patterson, a Private in The Auxiliary Territorial Service (ATS) is found dead in the sombre ruins of the medieval Kirkstall Abbey. She is the first victim, but others follow, and Lottie and McMillan are soon convinced that the killer is a member of the American forces based in the city.

So, Lottie is back in uniform again, but this time as a lowly member of the Women’s Auxiliary Police Corps. Her main job is to drive her boss, Detective Superintendent McMillan, to wherever he needs to go. McMillan, a veteran of The Great War, certainly needs his transport as a killer seems to be stalking vulnerable young women across the city. Kate Patterson, a Private in The Auxiliary Territorial Service (ATS) is found dead in the sombre ruins of the medieval Kirkstall Abbey. She is the first victim, but others follow, and Lottie and McMillan are soon convinced that the killer is a member of the American forces based in the city. You will note the date – spring 1944 – and will not need a degree in military history to work out what those ‘vital operations’ might be. Invasion or no invasion, McMillan still has a job to do, and the murderer is eventually cornered. Don’t anticipate a comfortable outcome, however. Nickson (right) doesn’t do cosy, and the conclusion of this fine novel is as dark as a blacked out city street.

You will note the date – spring 1944 – and will not need a degree in military history to work out what those ‘vital operations’ might be. Invasion or no invasion, McMillan still has a job to do, and the murderer is eventually cornered. Don’t anticipate a comfortable outcome, however. Nickson (right) doesn’t do cosy, and the conclusion of this fine novel is as dark as a blacked out city street.

HIRAMIC BROTHERHOOD, Ezekiel’s Temple Prophecy – written by

HIRAMIC BROTHERHOOD, Ezekiel’s Temple Prophecy – written by  COLD BLOOD – written by

COLD BLOOD – written by  THE YEAR OF THE GUN – written by

THE YEAR OF THE GUN – written by

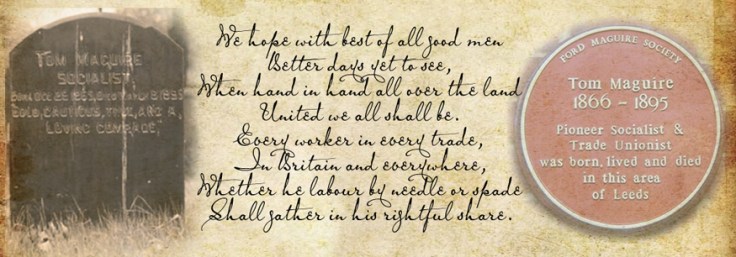

On Copper Street opens in grim fashion, with death and disfigurement. The dead pass in contrasting fashion. Socialist activist Tom Maguire dies in private misery, stricken by pneumonia and unattended by any of the working people whose status and condition he championed. The death of petty crook Henry White is more sudden, extremely violent, but equally final. Having only just been released from the forbidding depths of Armley Gaol, he is found on his bed with a fatal stab wound. If all this isn’t bad enough, two children working in a city bakery have been attacked by a man who threw acid in their faces. The girl will be marked for life, but at least she still has her sight. The last thing the poor lad saw – or ever will see – is the momentary horror of a man throwing acid at him. His sight is irreparably damaged.

On Copper Street opens in grim fashion, with death and disfigurement. The dead pass in contrasting fashion. Socialist activist Tom Maguire dies in private misery, stricken by pneumonia and unattended by any of the working people whose status and condition he championed. The death of petty crook Henry White is more sudden, extremely violent, but equally final. Having only just been released from the forbidding depths of Armley Gaol, he is found on his bed with a fatal stab wound. If all this isn’t bad enough, two children working in a city bakery have been attacked by a man who threw acid in their faces. The girl will be marked for life, but at least she still has her sight. The last thing the poor lad saw – or ever will see – is the momentary horror of a man throwing acid at him. His sight is irreparably damaged. Nickson is a master story teller. There are no pretensions, no gloomy psychological subtext, no frills, bows, fancies or furbelows. We are not required to wrestle with moral ambiguities, nor are we presented with any philosophical conundrums. This is not to say that the book doesn’t have an edge. I would imagine that Nickson (right) is a good old-fashioned socialist, and he pulls no punches when he describes the appalling way in which workers are treated in late Victorian England, and he makes it abundantly clear what he thinks of the chasm between the haves and the have nots. Don’t be put off by this. Nickson doesn’t preach and neither does he bang the table and browbeat. He recognises that the Leeds of 1895 is what it is – loud, smelly, bustling, full of stark contrasts, yet vibrant and fascinating. Follow this link to read our review of the previous Tom Harper novel,

Nickson is a master story teller. There are no pretensions, no gloomy psychological subtext, no frills, bows, fancies or furbelows. We are not required to wrestle with moral ambiguities, nor are we presented with any philosophical conundrums. This is not to say that the book doesn’t have an edge. I would imagine that Nickson (right) is a good old-fashioned socialist, and he pulls no punches when he describes the appalling way in which workers are treated in late Victorian England, and he makes it abundantly clear what he thinks of the chasm between the haves and the have nots. Don’t be put off by this. Nickson doesn’t preach and neither does he bang the table and browbeat. He recognises that the Leeds of 1895 is what it is – loud, smelly, bustling, full of stark contrasts, yet vibrant and fascinating. Follow this link to read our review of the previous Tom Harper novel,

Two gang bosses, one of Irish heritage and the other local, are engaged in a tense truce. They will hold off attacking each other while Harper and his fellow officers track down the mysterious copper-headed man who appears to be connected to the deaths. Time is running out, however, and there is an even more calamitous threat hanging over the heads of the police. The powers-that-be want answers, and as Harper runs around in ever decreasing circles, he is told that if he doesn’t find the killer, then men from Scotland Yard will travel north and take over the case. This, for Harper and his boss Superintendent Kendall, will be the ultimate disgrace.

Two gang bosses, one of Irish heritage and the other local, are engaged in a tense truce. They will hold off attacking each other while Harper and his fellow officers track down the mysterious copper-headed man who appears to be connected to the deaths. Time is running out, however, and there is an even more calamitous threat hanging over the heads of the police. The powers-that-be want answers, and as Harper runs around in ever decreasing circles, he is told that if he doesn’t find the killer, then men from Scotland Yard will travel north and take over the case. This, for Harper and his boss Superintendent Kendall, will be the ultimate disgrace.