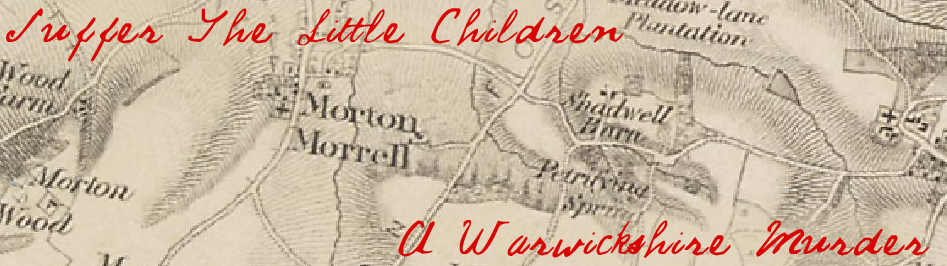

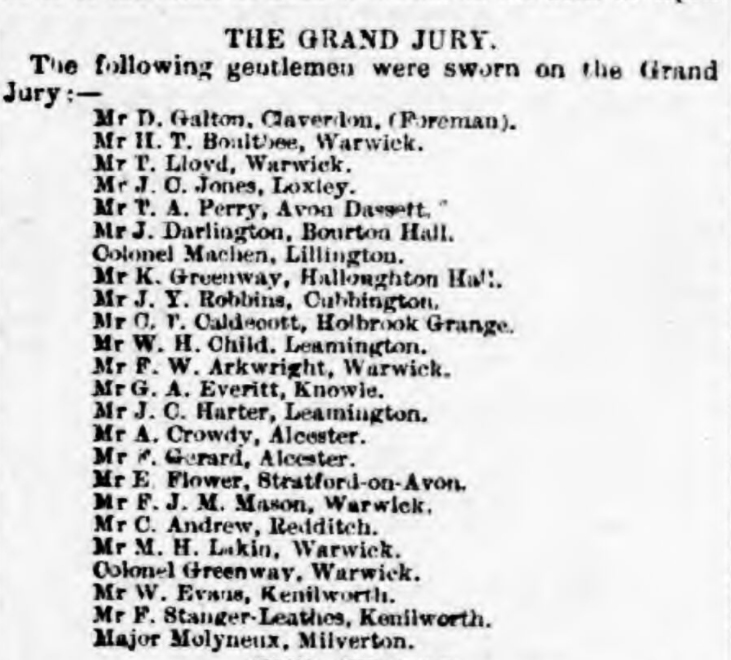

SO FAR – It is January 1949. Two men, Edward Sullivan (49) and Gordon Towle (19) have been working on a Leamington building site near what is now Westlea Road. There has been friction between them, with Great War veteran Sullivan (left) apparently sneering at Towle because the latter had not done his bit in the armed forces.

SO FAR – It is January 1949. Two men, Edward Sullivan (49) and Gordon Towle (19) have been working on a Leamington building site near what is now Westlea Road. There has been friction between them, with Great War veteran Sullivan (left) apparently sneering at Towle because the latter had not done his bit in the armed forces.

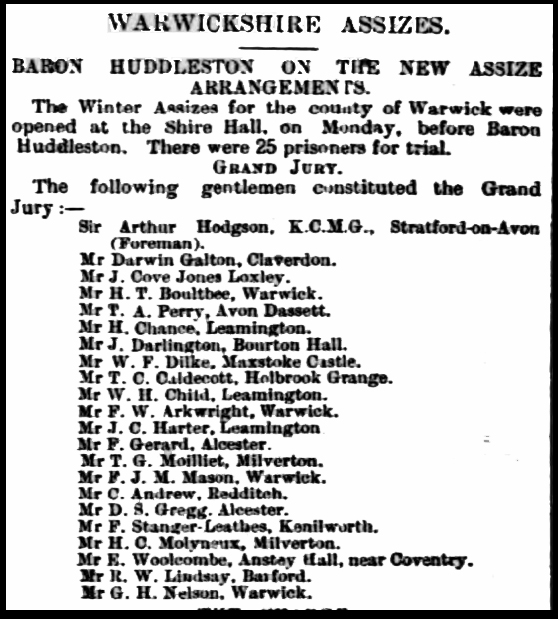

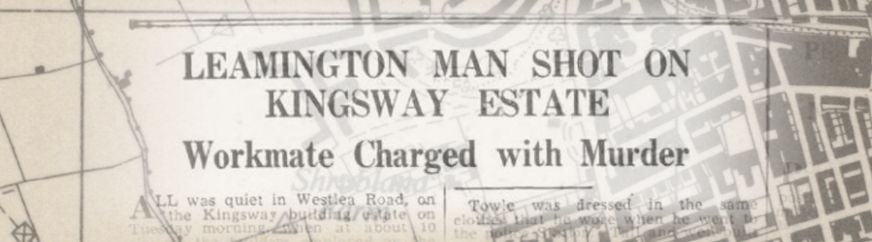

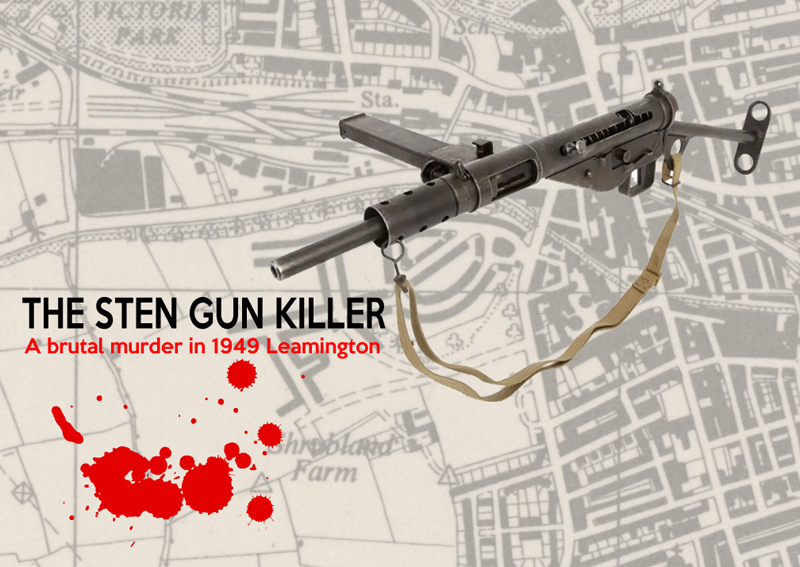

The events of Tuesday 25th January 1949 were to shock and mesmerise local people. At Leamington Police Station on the High Street it was 10.20am, and senior officers Inspector Green and Superintendent Gardner were leaving to carry out a routine inspection, when a burly, broad-shouldered young man entered the station. He was carrying what appeared to be a Sten gun. He said, quite calmly and without drama:

“I have shot a man. I am ill”

Green said, with some incredulity:

“Do you know what you are saying?”

The young man, who identified himself as Gordon Towle, handed the Inspector the Sten gun, along with an empty magazine and a magazine loaded with live 9mm bullets, and said:

“He has been pulling my leg and something came Into my head. I do silly things when I am funny like that. I think I have killed him. He is on the Bury Road estate; go to him. My head went funny and I shot him. I was not in the Army and they got on to me”

Towle was placed in a cell, and the officers took a police car and soon arrived at the building site. There lying in a pool of blood was the body of a man, later identified as Edward Sullivan. Around his body were found no fewer than 24 empty 9 mm. Sten gun cartridge cases – a full magazine holds 28 – and digging operations brought to light more bullets. Some were also found embedded in a nearby timber stack. When the police surgeon Dr. D. F. Lisle Croft arrived and examined the body, he was only able pronounce life extinct.

Towle was placed in a cell, and the officers took a police car and soon arrived at the building site. There lying in a pool of blood was the body of a man, later identified as Edward Sullivan. Around his body were found no fewer than 24 empty 9 mm. Sten gun cartridge cases – a full magazine holds 28 – and digging operations brought to light more bullets. Some were also found embedded in a nearby timber stack. When the police surgeon Dr. D. F. Lisle Croft arrived and examined the body, he was only able pronounce life extinct.

Events now moved on at pace. Chief Superintendent Alec Spooner, Head of Warwickshire CID was called, but that was a formality; there was little or no detective work required here. The first member of the Sullivan family to be told of the tragedy was son John, home on leave from the army. He had the melancholy task of telling his mother, Katherine Margaret Sullivan, that she was a widow. Above right, Towle is pictured being taken to the preliminary magistrate’s hearing.

In a newspaper report of one of Towle’s appearance before the magistrates, the journalist certainly exercised his imagination. Under a lurid headline headline, he described the scene thus:

“An unusually strong winter sun shone through the stained-glass windows of the Town Hall Council Chamber Wednesday, etching on the floor pattern in deep scarlet and blue. As the minutes went by, the shadow moved slowly and silently across the linoleum, and equally inexorably, quietly and persuasively, Mr. J. F. Claxton (for the Director of Public Prosecutions) outlined the history of the Kingsway Estate shooting on January 25th. Beside policeman, sat 19-year-old Gordon Towle, husband of less than six months, charged with murder. According a statement alleged have been made by him, Towle could no longer stand the taunts of a workmate, and so produced a Sten gun and fired two – or three, for the number is In doubt – bursts into the body of Edward Sullivan (49), Irishman, 6, Swadling Street, Leamington.

A full public gallery heard that Sullivan was killed outright by the ten bullets which entered his body in every vital part. The proceedings were intently listened by his widow and daughter – both in deep mourning – and his son, whose Army battle dress bore, the left arm. a narrow black band. In the afternoon, when only three of the fourteen called to give evidence remained to be heard, the Court had to move into an ante-room to make way for the tea organised by the Church England Zenana Missionary Society.

Only three members of the public, the widow, the daughter and one other lady, remained. Towle, dressed a sports coat and grey flannels, with an open necked cricket shirt, appeared to take a keen interest in all that was being said, but it was noticeable that at the end of the hearing, he blinked and then screwed face as if trying desperately hard to understand what was being said to him. He was asked if he had anything to say or any witnesses to call, and replied, quite firmly “No. sir.” — the only time he spoke throughout the hearing. But as he went to regain his seat, he stumbled little though about to fall. He sat down and heard the formality of his committal for trial at Warwick Assizes”

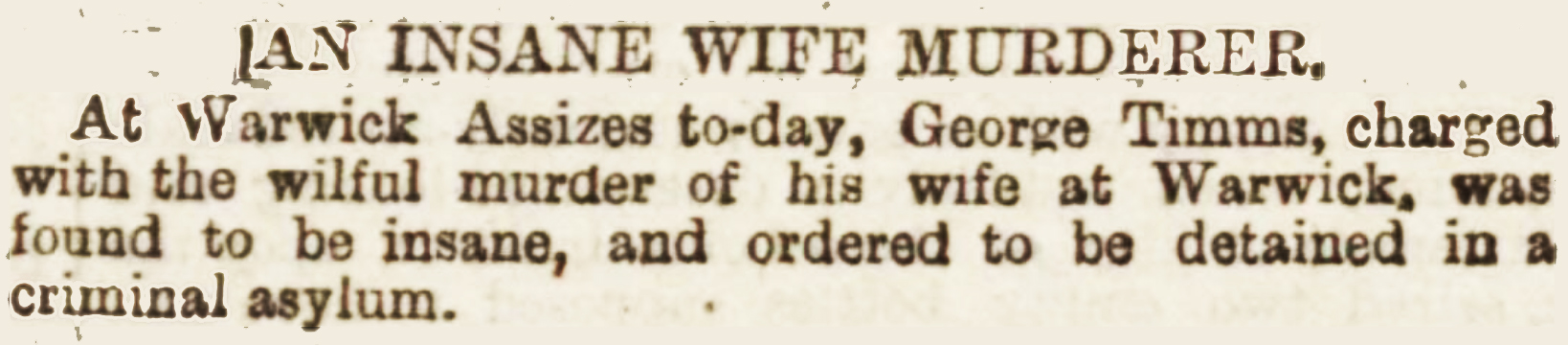

Gordon Towle’s time in front of Mr Justice Lynskey (left) at the March Assizes in Warwick was short – if far from sweet. Doctors gave evidence that he was quite mad, and he was sentenced to spend the rest of his days in a secure mental unit. The most puzzling matter for me was how Towle came to in possession of a Sten gun. He told the court that he had simply “pinched it” from the local drill hall, (probably the one in Clarendon Terrace) and stole the ammunition – police later found hundreds of live rounds in his house – from “an aerodrome”.

Gordon Towle’s time in front of Mr Justice Lynskey (left) at the March Assizes in Warwick was short – if far from sweet. Doctors gave evidence that he was quite mad, and he was sentenced to spend the rest of his days in a secure mental unit. The most puzzling matter for me was how Towle came to in possession of a Sten gun. He told the court that he had simply “pinched it” from the local drill hall, (probably the one in Clarendon Terrace) and stole the ammunition – police later found hundreds of live rounds in his house – from “an aerodrome”.

A postscript, which may bring a touch of humour to an otherwise dark tale. I can vouch for the inventive ways Army quartermasters had of “balancing the books.” regarding missing firearms. Back in the day, I taught at a public school in Cambridgeshire. The school Cadet Corps was being wound up, and an old sweat arrived from Waterbeach barracks to take an inventory of the firearms. To his dismay, he discovered that the armoury held one too many Lee Enfield rifles. This sent him into a lather, as it was apparently simple to account for missing guns on an inventory. They could just be written off as damaged or stripped for parts. But one too many? This was serious, and could only be remedied by a couple of squaddies rowing out in a boat one dark night on a local gravel pit, and dropping the offending item over the side, never to be seen again.

FOR MORE LEAMINGTON, WARWICK & DISTRICT

TRUE CRIME STORIES, CLICK HERE.

Swadling Street in Leamington is an unassuming thoroughfare, with houses which were built on the old Shrubland Estate between the wars. It was named after a Leamington councillor of the 1920s, and in 1931 it boasted twenty addresses. In January 1949, number 6 was occupied by Edward Sullivan. A 49 year-old Irishman and father of six children – three sons and three daughters – he worked as a builder’s labourer. Known to his mates – inevitably – as Paddy – he was working on a council house building project on Westlea Road, which was another between-wars development on what had been the Shrubland Estate.

Swadling Street in Leamington is an unassuming thoroughfare, with houses which were built on the old Shrubland Estate between the wars. It was named after a Leamington councillor of the 1920s, and in 1931 it boasted twenty addresses. In January 1949, number 6 was occupied by Edward Sullivan. A 49 year-old Irishman and father of six children – three sons and three daughters – he worked as a builder’s labourer. Known to his mates – inevitably – as Paddy – he was working on a council house building project on Westlea Road, which was another between-wars development on what had been the Shrubland Estate.