This is the next instalment of the career of Lancashire DS Jessica Raker, to whom we were introduced in “Death at Dead Man’s Stake”. Jess resumes her head-to-head battle with gang boss Maggie Horsefield, a ruthless and vindictive woman who is at the apex of the criminal fraternity, but someone who swims in the toxic waste in terms of human decency. It complicates matters that Jess’s daughter Lily and Maggie’s offspring Caitlin are BFFs at school.

It’s fair to say that Jessica Raker has something of a turbulent past. Born and bred in the district she now polices, she gravitated to London, where her career in the Metropolitan Police concluded dramatically with her shooting dead a feckless younger member of a serious crime gang. When a retaliatory contract was taken out on her life, she was relocated to Clitheroe. She has two children, but her relationship with husband Josh is, to say the least, threadbare, although they are still together.

This story starts with Lance Drake, a petty crook somewhere near the bottom of Maggie Horsefield’s barrel of criminal employees, facing his worst nightmare. He is being released on license from HMP Preston, where he has been quite happily spending the last few months, safe from the inevitable retribution which has awaited him since he shot his mouth off to the police, thus losing his boss tens of thousands of pounds in a drug shipment.

Inevitably, given that Horsefield has her employees embedded at every level of the criminal justice system, Drake is soon grabbed, and when the hood is taken from his head, he finds himself cable-tied to a chair sitting, ominously, on a large plastic sheet spread on the floor of a disused mill, with Horsefield sitting nearby, fondling a zombie knife. Jess Raker’s team have had their eyes on this mill for some time, rightly suspecting that is part of Horsefield’s drug distribution business and, happily for Lance Drake, they choose that moment for a raid.

Most of Horsefield’s goons get away, the mill plus an industrial quantity of ‘merchandise’ go up in flames, and the stage is set for a dramatic encounter as Horsefield and her lover, London gangster Tommy Moss, plan a multi-million pound raid on Wolf Fell Hall, an ancestral home which contains scores of priceless old master paintings. Along the way, we learn more about the team of officers around Jessica Raker. There is the intelligent and resourceful PCSO Samira Patel, who yearns to become a ‘proper’ copper. CID officer Dougie Doolan is one of Jessica’s mainstays, but she suspects he is hiding a grim secret. Her boss, Inspector Price, we strongly suspect may be a wrong ‘un, but is he actually feeding information to the dreadful Maggie Horsefield?

One thing you will not find in a Nick Oldham novel, thankfully, is the remotest trace of sympathetic hand-wringing for his villains. Yes they may come from awful families with dreadful parents but, like all of us, they have a choice. If they take the wrong road, then they have no-one to blame but themselves. For Oldham, once a working copper in hives of scum and villainy like Blackpool, they have made their choice and deserve everything they get. He has a direct, no-frills narrative style. The sheer readability of his novels is based on superb storytelling, and an unparalleled knowledge of English policing, woven together with a sense of place, location and topography designed to draw the reader into the narrative. Death on Wolf Fell will be published by Severn House on 6th May.

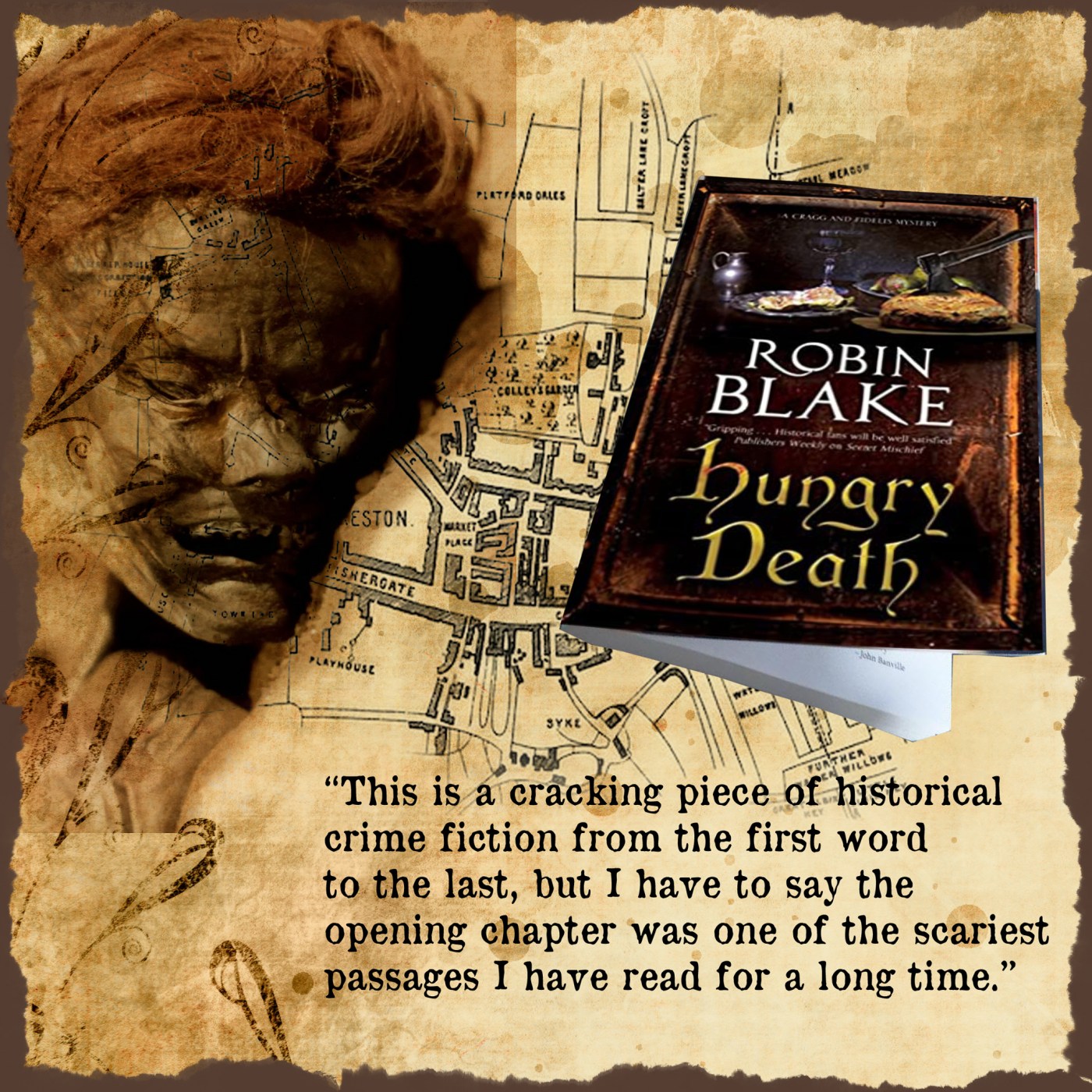

Cragg is instructed to ride out to a lonely moorland farmhouse, and what he finds surpasses any of the previous horrors his calling requires him to confront. He finds an entire family slaughtered, by whose hand he knows not, unless it was the husband of the house, himself hanging by a strap hooked over a beam. To add even more mystery to the grisly tableau, Cragg learns that the KIdd family were members of a bizarre dissenting cult which encourages its members into acts of brazen sexuality. Then, in a seemingly unconnected incident, the gardener at a nearby mansion, trying to improve the drainage under his hothouse, discovers another body. This corpse may have been in the ground for centuries, as it has been partly preserved by the peat in which it was buried. When Fidelis conducts an autopsy, however, he concludes that the body is that of a young woman, and was probably put in the ground within the last decade or so.

Cragg is instructed to ride out to a lonely moorland farmhouse, and what he finds surpasses any of the previous horrors his calling requires him to confront. He finds an entire family slaughtered, by whose hand he knows not, unless it was the husband of the house, himself hanging by a strap hooked over a beam. To add even more mystery to the grisly tableau, Cragg learns that the KIdd family were members of a bizarre dissenting cult which encourages its members into acts of brazen sexuality. Then, in a seemingly unconnected incident, the gardener at a nearby mansion, trying to improve the drainage under his hothouse, discovers another body. This corpse may have been in the ground for centuries, as it has been partly preserved by the peat in which it was buried. When Fidelis conducts an autopsy, however, he concludes that the body is that of a young woman, and was probably put in the ground within the last decade or so.

As ever, murder is the word, and a series of deaths in and around the town of Omskirk are linked to an archaic form of business plan for raising money, known as a Tontine. The investment plan was named after Neapolitan banker Lorenzo de Tonti and, to put it simply, was a pot of money where a number of people contributed an equal sum. The money would either be invested, with interest paid to the members, or used to fund capital projects. As time went on, and investors died, the fund became the property of the remaining members, until the last man (or woman) standing hit the jackpot.

As ever, murder is the word, and a series of deaths in and around the town of Omskirk are linked to an archaic form of business plan for raising money, known as a Tontine. The investment plan was named after Neapolitan banker Lorenzo de Tonti and, to put it simply, was a pot of money where a number of people contributed an equal sum. The money would either be invested, with interest paid to the members, or used to fund capital projects. As time went on, and investors died, the fund became the property of the remaining members, until the last man (or woman) standing hit the jackpot. One by one the Tontine signatories come to sticky ends: one is, apparently, hit by the sail of a windmill; another is found dead on Crosby beach, apparently drowned, but Luke Fidelis conducts a post mortem and finds that the dead man’s body has been dumped on the seashore. Things become even more complex when a reformed ‘lady of the night’, now a maid, is accused of pushing the poor woman into the path of the windmill sail. Cragg is convinced she is innocent, but faces an uphill struggle against a corrupt judge.

One by one the Tontine signatories come to sticky ends: one is, apparently, hit by the sail of a windmill; another is found dead on Crosby beach, apparently drowned, but Luke Fidelis conducts a post mortem and finds that the dead man’s body has been dumped on the seashore. Things become even more complex when a reformed ‘lady of the night’, now a maid, is accused of pushing the poor woman into the path of the windmill sail. Cragg is convinced she is innocent, but faces an uphill struggle against a corrupt judge.

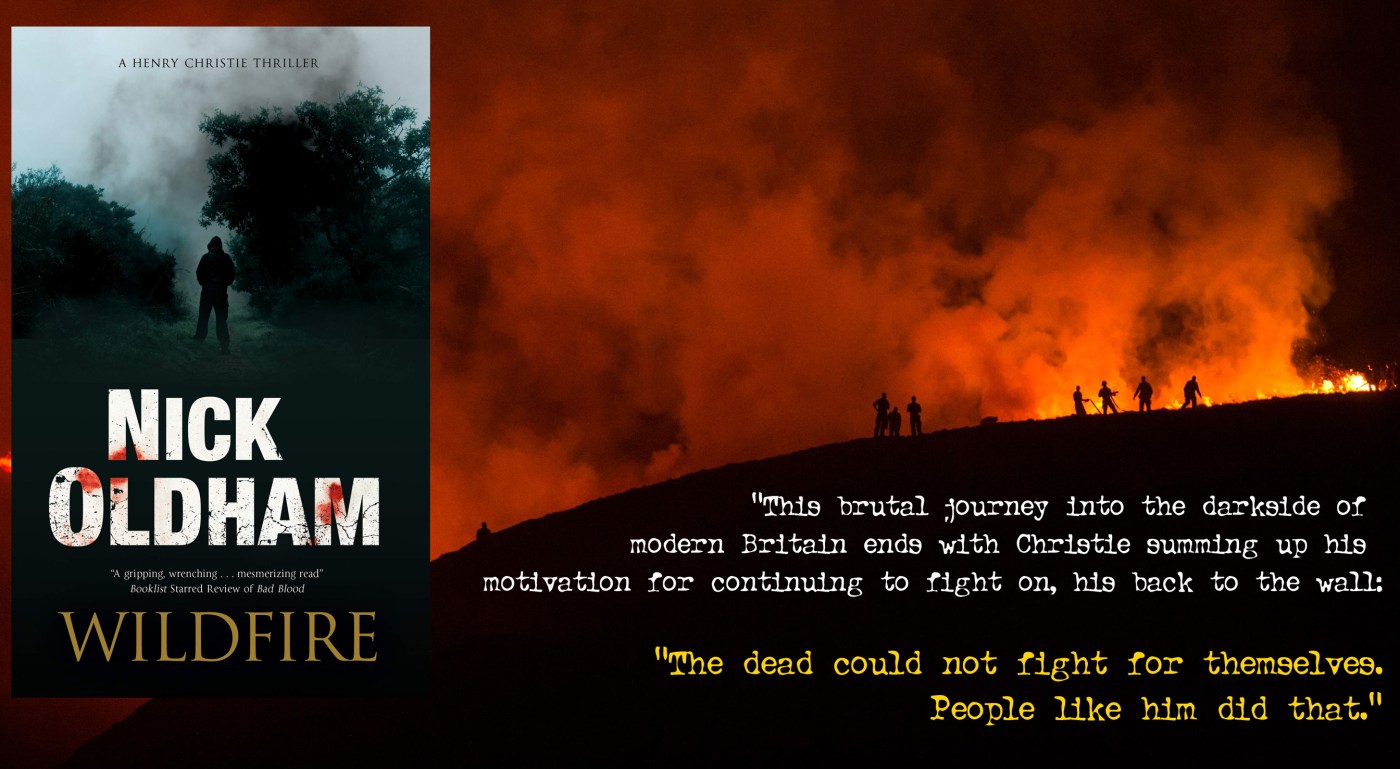

ack in the day, before authors and their publishers trusted me with reviewing novels, I did what the vast majority of the reading public did – I either bought books when I could afford them or I went to the local library. I had a list of authors whose latest works I would grab eagerly, or take my place in the queue of library members who had reserved copies. In no particular order, anything by John Connolly, Jim Kelly, Phil Rickman, Frank Tallis, Philip Kerr, Mark Billingham, Christopher Fowler and Nick Oldham would be like gold dust.

ack in the day, before authors and their publishers trusted me with reviewing novels, I did what the vast majority of the reading public did – I either bought books when I could afford them or I went to the local library. I had a list of authors whose latest works I would grab eagerly, or take my place in the queue of library members who had reserved copies. In no particular order, anything by John Connolly, Jim Kelly, Phil Rickman, Frank Tallis, Philip Kerr, Mark Billingham, Christopher Fowler and Nick Oldham would be like gold dust. Oldham’s Henry Christie was a particular favourite, as his adventures mixed excellent police procedure – thanks to Oldham’s career as a copper – a vulnerable and likeable hero, and an unflinching look at the mean and vicious streets of the Blackpool area in England’s north-west. Wildfire is the latest outing for Henry Christie, who has retired from the police and now runs a pleasant village pub set in the Lancashire hills.

Oldham’s Henry Christie was a particular favourite, as his adventures mixed excellent police procedure – thanks to Oldham’s career as a copper – a vulnerable and likeable hero, and an unflinching look at the mean and vicious streets of the Blackpool area in England’s north-west. Wildfire is the latest outing for Henry Christie, who has retired from the police and now runs a pleasant village pub set in the Lancashire hills.

ventually, the wildfires of both kinds are extinguished, at least temporarily, but not before Henry Christie is forced, yet again, to take a long hard look at himself in the mirror, and question if it was all worth the effort.

ventually, the wildfires of both kinds are extinguished, at least temporarily, but not before Henry Christie is forced, yet again, to take a long hard look at himself in the mirror, and question if it was all worth the effort. his brutal journey into the darkside of modern Britain ends with Christie summing up his motivation for continuing to fight on, his back to the wall:

his brutal journey into the darkside of modern Britain ends with Christie summing up his motivation for continuing to fight on, his back to the wall:

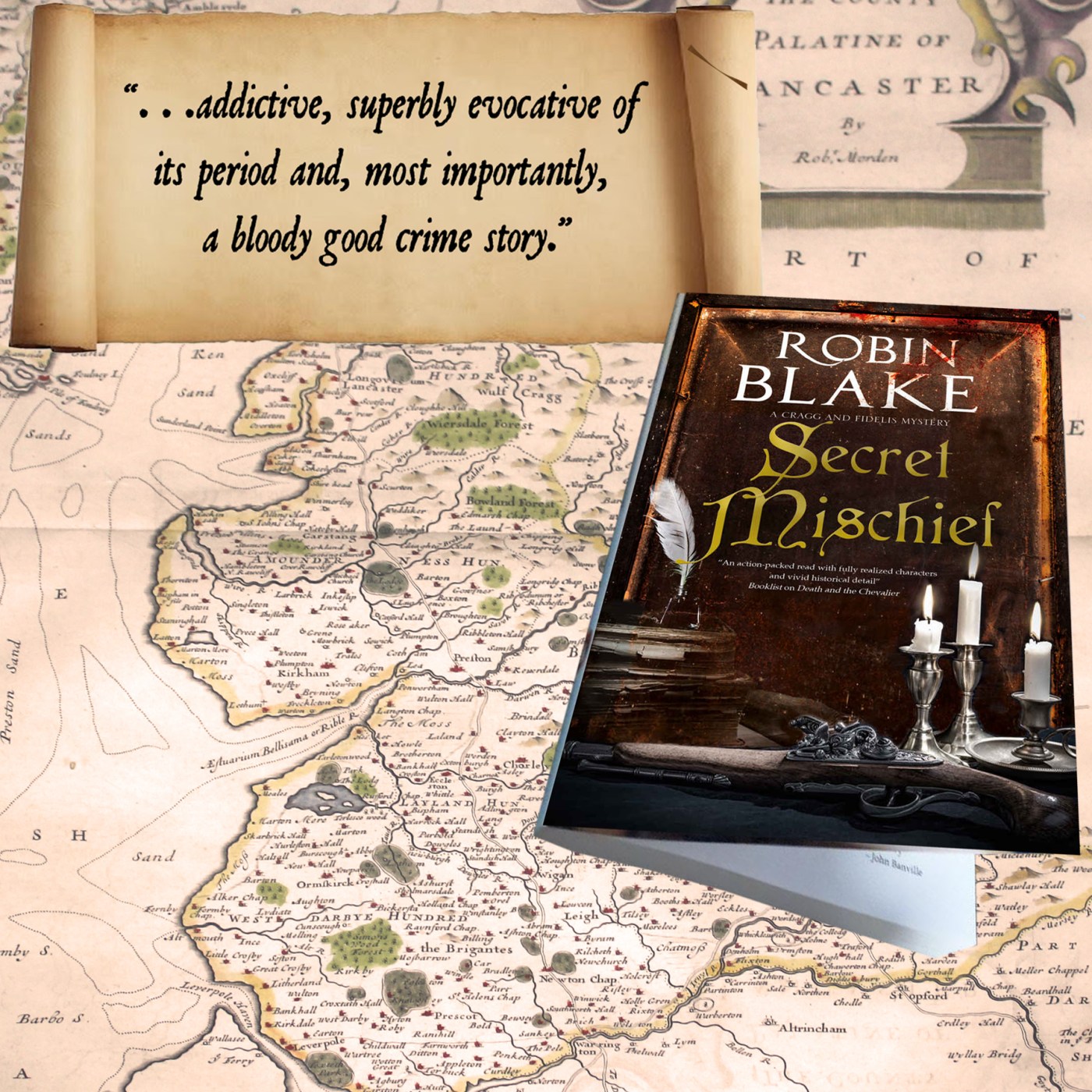

Robin Blake (left) introduced us to Preston coroner Titus Cragg and his physician friend Luke Fidelis in A Dark Anatomy back in 2015, and the pair of eighteenth century sleuths are back again with their fifth case, Rough Music.

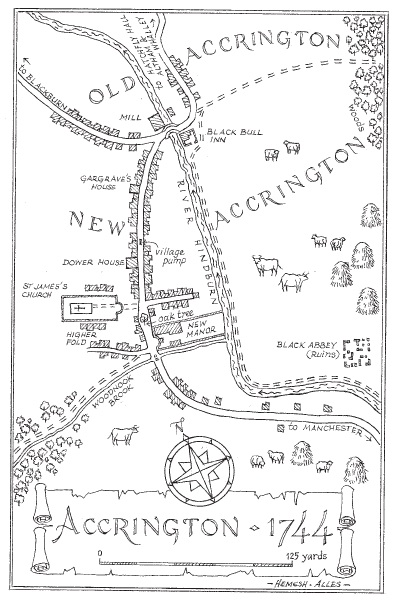

Robin Blake (left) introduced us to Preston coroner Titus Cragg and his physician friend Luke Fidelis in A Dark Anatomy back in 2015, and the pair of eighteenth century sleuths are back again with their fifth case, Rough Music. Titus Cragg with his wife and child have retreated from Preston to escape the ravages of a viral illness which has claimed the lives of many infants. They have fetched up in a rented house in Accrington, then little more than a scattering of houses beside a stream. Cragg is drawn into the investigation of how it was that Anne Gargrave died at the hands of her fellow villagers, but his work is complicated by a feud between two rival squires, a mysterious former soldier who may have assumed someone else’s identity, and the difficulty created by Luke Fidelis becoming smitten by the beguiling – but apparently mistreated – wife of a choleric and impetuous local landowner.

Titus Cragg with his wife and child have retreated from Preston to escape the ravages of a viral illness which has claimed the lives of many infants. They have fetched up in a rented house in Accrington, then little more than a scattering of houses beside a stream. Cragg is drawn into the investigation of how it was that Anne Gargrave died at the hands of her fellow villagers, but his work is complicated by a feud between two rival squires, a mysterious former soldier who may have assumed someone else’s identity, and the difficulty created by Luke Fidelis becoming smitten by the beguiling – but apparently mistreated – wife of a choleric and impetuous local landowner. I have to admit to a not-so-guilty-pleasure taken from reading historical crime fiction, and I can say with some certainty that one of the things Robin Blake does so well is the way he handles the dialogue. No-one can know for certain how people in the eighteenth century- or any other era before speech could be recorded – spoke to each other. Formal written or printed sources would be no more a true indication than a legal document would be today, so it is not a matter of scattering a few “thees” and “thous” around. For me, Robin Blake gets it spot on. I can’t say with authority that the way Titus Cragg talks is authentic, but it is convincing and it works beautifully.

I have to admit to a not-so-guilty-pleasure taken from reading historical crime fiction, and I can say with some certainty that one of the things Robin Blake does so well is the way he handles the dialogue. No-one can know for certain how people in the eighteenth century- or any other era before speech could be recorded – spoke to each other. Formal written or printed sources would be no more a true indication than a legal document would be today, so it is not a matter of scattering a few “thees” and “thous” around. For me, Robin Blake gets it spot on. I can’t say with authority that the way Titus Cragg talks is authentic, but it is convincing and it works beautifully.

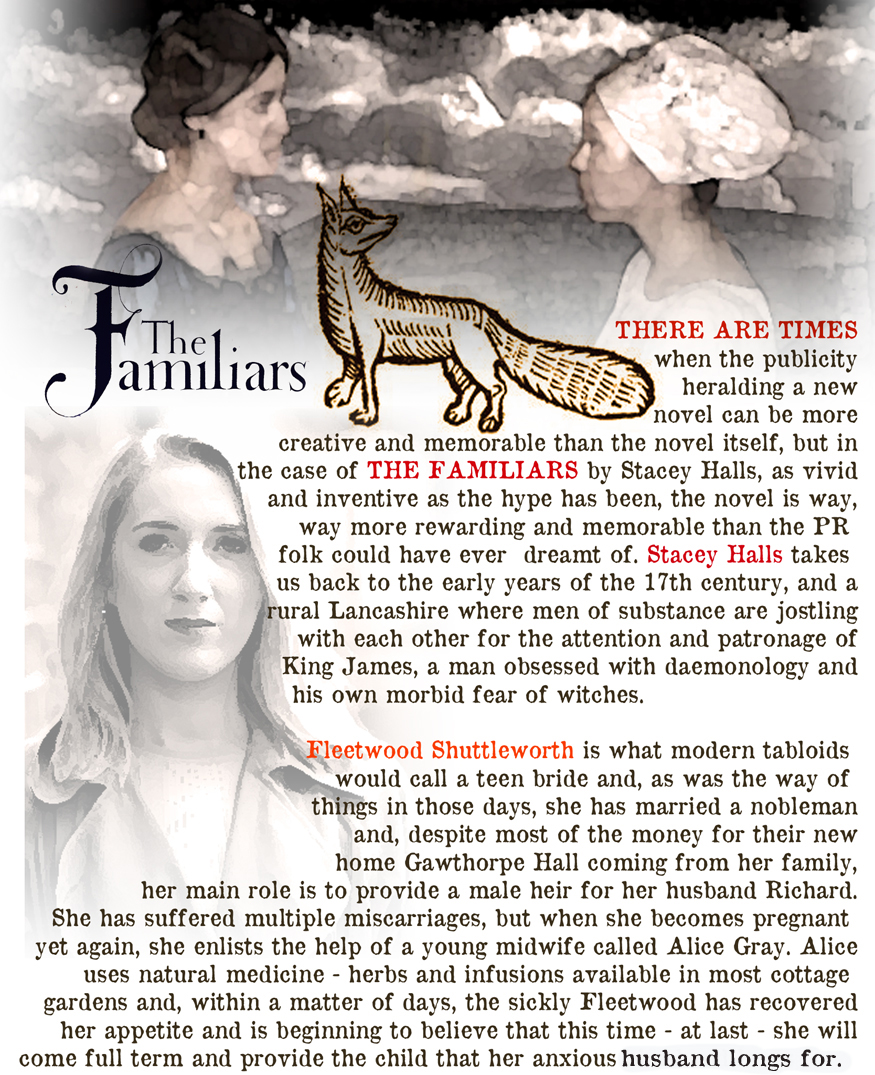

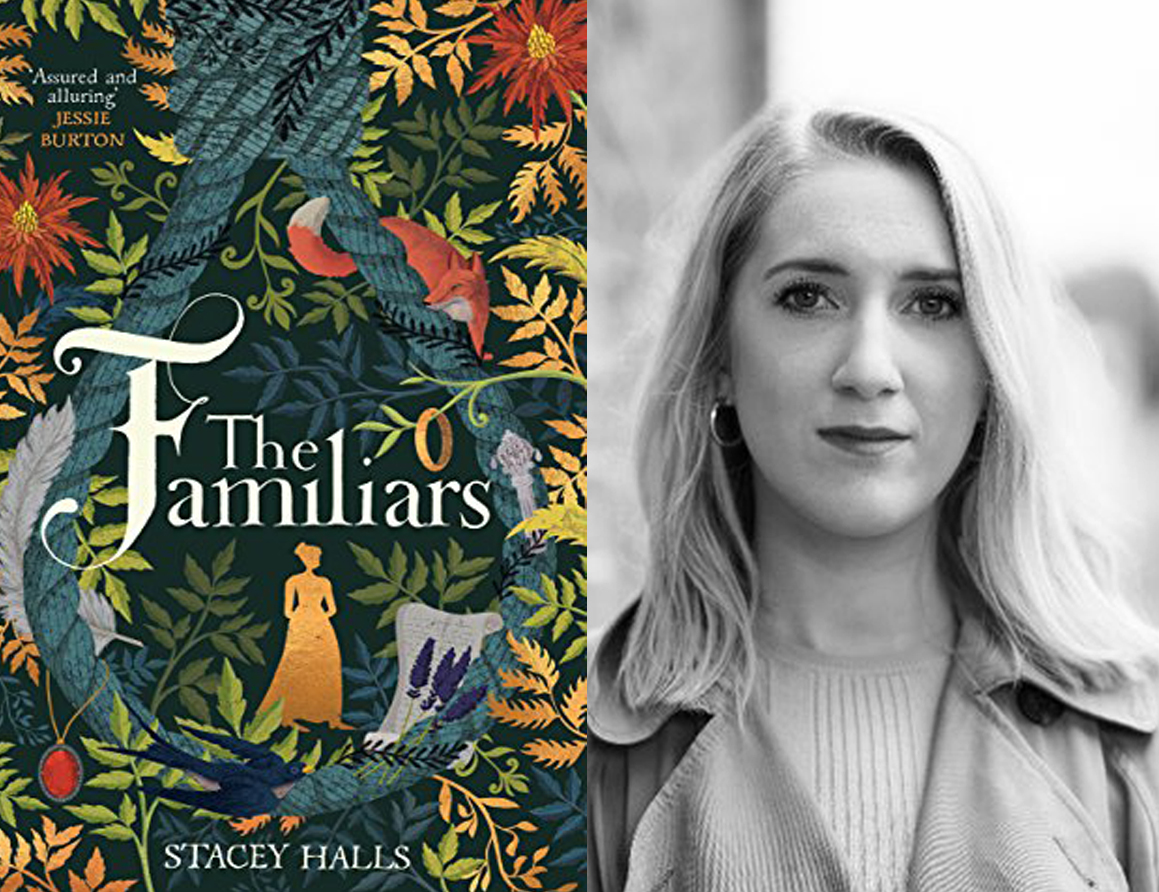

AT THE APPROPRIATELY NAMED DEAD DOLLS HOUSE in Islington, the inventive folks at publishers Bonnier Zaffre launched Stacy Halls’ novel The Familiars with not so much a flourish as a brilliant visual fanfare.

AT THE APPROPRIATELY NAMED DEAD DOLLS HOUSE in Islington, the inventive folks at publishers Bonnier Zaffre launched Stacy Halls’ novel The Familiars with not so much a flourish as a brilliant visual fanfare. witchy tinctures using a potent combination of various precious oils. I went for Frankincense with a dash of Patchouli. I managed to smear it everywhere and such was its potency that my wife was convinced that I had been somewhere less innocent than a book launch.

witchy tinctures using a potent combination of various precious oils. I went for Frankincense with a dash of Patchouli. I managed to smear it everywhere and such was its potency that my wife was convinced that I had been somewhere less innocent than a book launch.