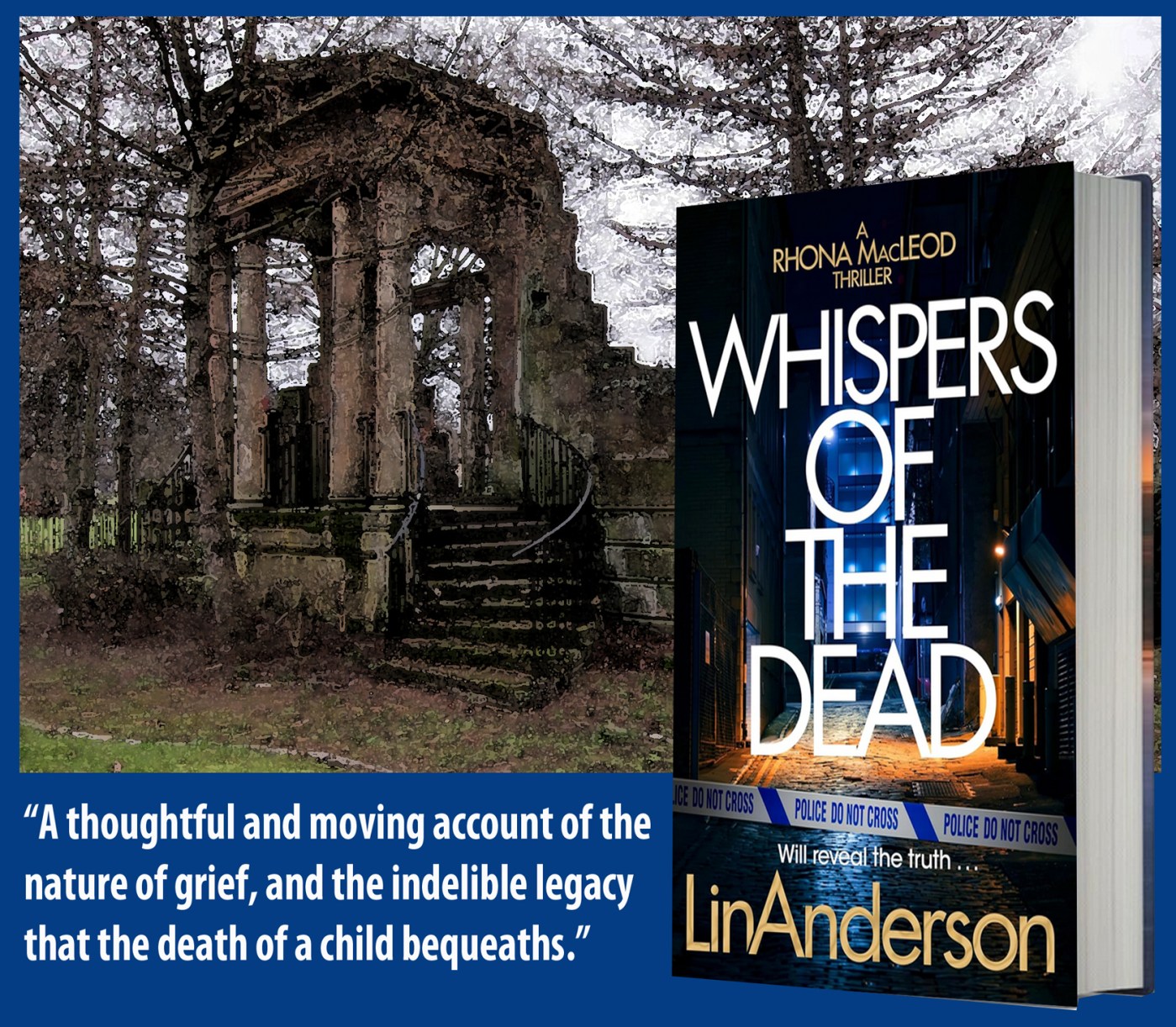

Lin Anderson’s battle-hardened forensic investigator Dr Rhona MacLeod returns to make another journey through the grisly physical mayhem that some human beings inflict on others. In a disused and vandalised farmhouse in Glasgow’s Elder Park, a man’s body has been found. His eyes and mouth have been sewn shut and, strapped to a metal chair, he has been thrown through an upstairs window. A trio of teenage scallies have been using the old building as a base for their minor law-breaking, and they are the first people to see the body,

In another part of the city, an American film crew have informed the police that their leading man is missing. With the assistance of DS McNab, who has interviewed the movie-makers, Rhona MacLeod becomes involved, and wonders if the missing actor is the mutilated corpse found in the park.

At the very beginning of the book Lin Anderson introduces what develops into a parallel plot thread. A woman called Marnie Aitken has served six years in prison for the murder of her four year-old daughter, Tizzy, despite the fact that no trace of Tizzy, dead or alive, has ever been found. Marnie is known to Rhona MacLeod, and to her colleague, psychiatrist Professor Magnus Pirie. On her release, Marnie – abused as a child and as a young woman – is placed in sheltered accommodation. She goes missing. but not before sending a bizarre gift to Rhona. It is a beautifully sewn and knitted doll, in the likeness of a young Highland dancer. Rhona realises its significance, as Tizzy Aitken was a promising dancer, but she is also appalled to see that the doll’s lips have been sewn shut with black thread. What message is Marnie sending?

Marnie is located at her old cottage on the Rosneath Peninsula, and but she returns to Glasgow, where the police find that she is linked – albeit at a tangent – the the killing of the man in Elder Park. Meanwhile, DS McNab – who was involved in the original investigation into Tizzy’s disappearance, but kicked off the case – has realised that the script and screenplay of the film – now abandoned after the disappearance of its star – is inextricably tangled up with the murder.

Right from the beginning of the novel, we know that Marnie still talks to Tizzy, and Tizzy still talks to her. Is this merely, as Magnus Pirie suggests, a grieving woman’s way of coping with her loss? Or is it something else? On the first page of the book, Marnie looks out of the window:

“It was at that moment the figure of a girl, dressed in a kilt and blue velvet jacket, arrived to tramp across the snow in front of the main gate. As though sensing someone watching, the girl stopped and turned to look over at her. Marnie stood transfixed, then shut her eyes, her heart hammering. ‘She’s not real. It’s a waking nightmare. When I look again, she won’t be there.’

And she was right.

When Marnie forced her eyes open, the figure had gone, or more likely, it had never been there in the first place except there were footprints in the snow to prove otherwise.”

When Rhona visits Marnie’s seaside cottage, she walks down to the beach where Tizzy used to go with her mother:

“The snow at sea level had gone and the muddy ruts were studded with puddles and the shape of footsteps leading both ways. Her forensic eye noted three in particular, ranging in size: a small childlike print, a medium one and a large one, going in both directions.”

Lin Anderson doesn’t resolve this for us. She leaves us to draw our conclusions, and I suppose it depends on how feel about Hamlet’s oft-quoted words to Horatio in Act 1 Scene 5 of the celebrated play. The police procedural part of this novel plays out in the favour of the good guys, but aside from this, Lin Anderson has written a thoughtful and moving account of the nature of grief, and the indelible legacy that the death of a child bequeaths. Whispers of The Dead was published by Macmillan on 1st August.

The trope of a police officer investigating a crime “off patch” or in an unfamiliar mileu is not new, especially in film. At its corniest, we had John Wayne in Brannigan (1975) as the Chicago cop sent to London to help extradite a criminal, and in Coogan’s Bluff (1968), Clint Eastwood’s Arizona policeman, complete with Stetson, is sent to New York on another extradition mission. Black Rain (1989) has Michael Douglas locking horns with the Yakuza in Japan, and who can forget Liam Neeson’s unkindness towards Parisian Albanians in Taken (2018), but apart from 9 Dragons (2009), where Michael Connolly’s Harry Bosch goes to war with the Triads in Hong Kong, I can’t recall many crime novels in the same vein. Rob McClure (left) balances this out with his debut novel, The Scotsman, which was edited by Luca Veste.

The trope of a police officer investigating a crime “off patch” or in an unfamiliar mileu is not new, especially in film. At its corniest, we had John Wayne in Brannigan (1975) as the Chicago cop sent to London to help extradite a criminal, and in Coogan’s Bluff (1968), Clint Eastwood’s Arizona policeman, complete with Stetson, is sent to New York on another extradition mission. Black Rain (1989) has Michael Douglas locking horns with the Yakuza in Japan, and who can forget Liam Neeson’s unkindness towards Parisian Albanians in Taken (2018), but apart from 9 Dragons (2009), where Michael Connolly’s Harry Bosch goes to war with the Triads in Hong Kong, I can’t recall many crime novels in the same vein. Rob McClure (left) balances this out with his debut novel, The Scotsman, which was edited by Luca Veste.

Alan Parks (left) introduced us to Glasgow cop

Alan Parks (left) introduced us to Glasgow cop

By 22nd March 2018, there should be catkins on the willow and hazel, daffodils should be getting into their stride and, even if it’s a little early to be looking for summer migrants like swallows and warblers, nothing will be more welcome to lovers of good crime fiction than the return of William Lorimer in another – the fifteenth, unbelievably – police procedural set in Scotland. Since Alex Gray (left) saw Never Somewhere Else published in 2002, she has made Lorimer and his world one of the go-to destinations for anyone who loves a well-crafted crime novel, with a sympathetically portrayed central character.

By 22nd March 2018, there should be catkins on the willow and hazel, daffodils should be getting into their stride and, even if it’s a little early to be looking for summer migrants like swallows and warblers, nothing will be more welcome to lovers of good crime fiction than the return of William Lorimer in another – the fifteenth, unbelievably – police procedural set in Scotland. Since Alex Gray (left) saw Never Somewhere Else published in 2002, she has made Lorimer and his world one of the go-to destinations for anyone who loves a well-crafted crime novel, with a sympathetically portrayed central character.