I don’t review too many non-crime novels on here, but this one really appealed to me. It begins in the 1970s in an unnamed English town. Tim and Abi are teenage twins and, like many such siblings, have an almost preternatural bond that often transcends the spoken word and visual communication. They also have what might be called an unhealthy fascination with ghosts and the paranormal. One of Tim’s hobbies is painting pictures of bygone execution methods, and their favourite book is a well worn copy of The End of Borley Rectory (1946) by Harry Price. Price was a well-known ‘ghost-hunter’ in the 1930s and 1940s and although he is widely regarded as a charlatan these days, he was a celebrated and popular author, particularly on the topic of Borley Rectory in Suffolk, once known as “the most haunted house in England”.

I don’t review too many non-crime novels on here, but this one really appealed to me. It begins in the 1970s in an unnamed English town. Tim and Abi are teenage twins and, like many such siblings, have an almost preternatural bond that often transcends the spoken word and visual communication. They also have what might be called an unhealthy fascination with ghosts and the paranormal. One of Tim’s hobbies is painting pictures of bygone execution methods, and their favourite book is a well worn copy of The End of Borley Rectory (1946) by Harry Price. Price was a well-known ‘ghost-hunter’ in the 1930s and 1940s and although he is widely regarded as a charlatan these days, he was a celebrated and popular author, particularly on the topic of Borley Rectory in Suffolk, once known as “the most haunted house in England”.

The twins are also keen photographers, but bear in mind that this is the 1970s, and unless you had a home darkroom, photography for most people involved taking the roll of film from the camera and handing it over to Boots to be developed and printed. Tim and Abi are connoisseurs of paranormal photography and, even though they do not have the expertise to create elaborate fakes such as the celebrated ghost that haunted The Queen’s House Greenwich (right), they have imagination to spare. They have sole use of the attic in their house, and their well-meaning but rather ‘hands-off’ parents seldom venture up the ladder into Tim and Abi’s terrain.

On a blank wall, they draw a rather convincing image of a tormented woman, and take a whole roll of photographs of it. Harmless fun? Yes, it might have been, until they decide to take one of the more convincing images to school, and show it to a classmate, backed up with an elaborate story that Abi has seen the ghost of a former occupant of their house, a young woman who, shamed by her cheating fiancé, hanged herself in that very attic. The victim of their prank is Janice Tupp, a seemingly unremarkable girl who the twins despise because of her very ordinariness. Rather like those who tormented Carrie White, they have picked the wrong victim. Janice collapses at school after being shown the photograph, and when, some days later, the twins invite her round to their house in order to explain their deception (and to avoid getting into serious trouble) Janice shocks them by making a puzzling prediction which Tim and Abi can make no sense of. A few weeks later, however, something shocking happens which will change everything – for ever.

On a blank wall, they draw a rather convincing image of a tormented woman, and take a whole roll of photographs of it. Harmless fun? Yes, it might have been, until they decide to take one of the more convincing images to school, and show it to a classmate, backed up with an elaborate story that Abi has seen the ghost of a former occupant of their house, a young woman who, shamed by her cheating fiancé, hanged herself in that very attic. The victim of their prank is Janice Tupp, a seemingly unremarkable girl who the twins despise because of her very ordinariness. Rather like those who tormented Carrie White, they have picked the wrong victim. Janice collapses at school after being shown the photograph, and when, some days later, the twins invite her round to their house in order to explain their deception (and to avoid getting into serious trouble) Janice shocks them by making a puzzling prediction which Tim and Abi can make no sense of. A few weeks later, however, something shocking happens which will change everything – for ever.

Further references by me to specifics of the plot will be, perforce, cautious, as I have no wish to diminish readers’ enjoyment – if that is the right word. I add that caveat, because Will Maclean takes us into very dark territory. Suffice it to say that Tim becomes involved with two researchers and a group of people more or less his own age who have rented an old Suffolk manor house with the purpose of conducting experiments into the paranormal. At this point, cynical readers are entitled to use the cliché “And what could possibly go wrong…?” but Maclean skillfully avoids the more obvious pitfalls, and steers an intriguing course between Hamlet’s famous statement to Horatio, and our knowledge of the nature of reality and deception.

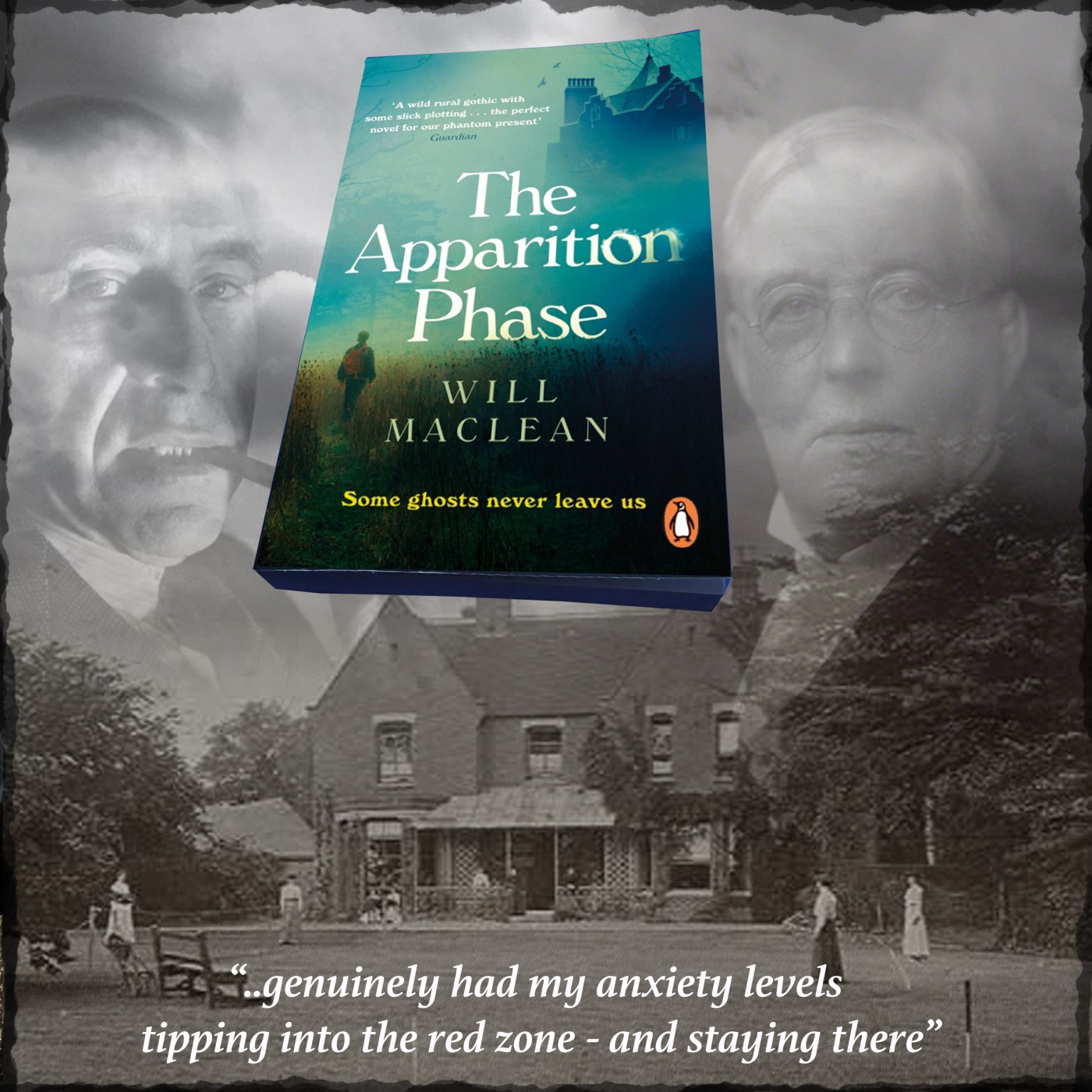

I wouldn’t say that I am a blasé reader, but any reviewer of mostly crime and thriller novels encounters fictional grief and trauma on a daily basis. The Apparition Phase genuinely had my anxiety levels tipping into the red zone – and staying there. Will Maclean references the unrivaled master of ghost stories – MR James – but in a sense, he goes one better. James wrote short stories, and therefore had only to keep the menace going for twenty pages or so, but to keep us engaged and anxious for four hundred is something else altogether.

This deeply unsettling novel, published by William Heinemann, came out in paperback earlier this month and will be available in Kindle and hardback on 29th October

he racial element in South-set crime fiction over the last half century is peculiar in the sense that there have been few, if any, memorable black villains. There are plenty of bad black people in Walter Mosley’s novels, but then most of the characters in them are black, and they are not set in what are, for the purposes of this feature, our southern heartlands.

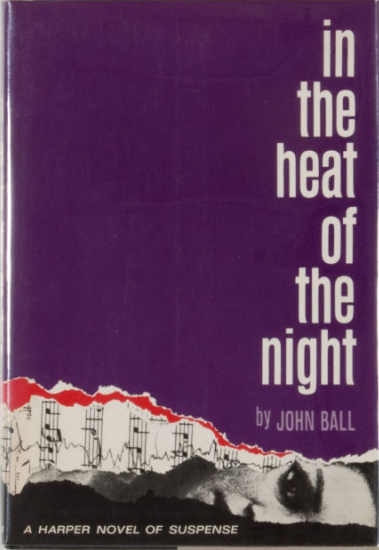

he racial element in South-set crime fiction over the last half century is peculiar in the sense that there have been few, if any, memorable black villains. There are plenty of bad black people in Walter Mosley’s novels, but then most of the characters in them are black, and they are not set in what are, for the purposes of this feature, our southern heartlands. Black characters are almost always good cops or PIs themselves, like Virgil Tibbs in John Ball’s In The Heat of The Night (1965), or they are victims of white oppression. In the latter case there is often a white person, educated and liberal in outlook, (prototype Atticus Finch, obviously) who will go to war on their behalf. Sometimes the black character is on the side of the good guys, but intimidating enough not to need help from their white associate. John Connolly’s Charlie Parker books are mostly set in the northern states, but Parker’s dangerous black buddy Louis is at his devastating best in The White Road (2002) where Parker, Louis and Angel are in South Carolina working on the case of a young black man accused of raping and killing his white girlfriend.

Black characters are almost always good cops or PIs themselves, like Virgil Tibbs in John Ball’s In The Heat of The Night (1965), or they are victims of white oppression. In the latter case there is often a white person, educated and liberal in outlook, (prototype Atticus Finch, obviously) who will go to war on their behalf. Sometimes the black character is on the side of the good guys, but intimidating enough not to need help from their white associate. John Connolly’s Charlie Parker books are mostly set in the northern states, but Parker’s dangerous black buddy Louis is at his devastating best in The White Road (2002) where Parker, Louis and Angel are in South Carolina working on the case of a young black man accused of raping and killing his white girlfriend. hosts, either imagined or real, are never far from Charlie Parker, but another fictional cop has more than his fair share of phantoms. James Lee Burke’s Dave Robicheaux frequently goes out to bat for black people in and around New Iberia, Louisiana. Robicheaux’s ghosts are, even when he is sober, usually that of Confederate soldiers who haunt his neighbourhood swamps and bayous. I find this an interesting slant because where John Connolly’s Louis will wreak havoc on a person who happens to have the temerity to sport a Confederate pennant on his car aerial, Robicheaux’s relationship with his CSA spectres is much more subtle.

hosts, either imagined or real, are never far from Charlie Parker, but another fictional cop has more than his fair share of phantoms. James Lee Burke’s Dave Robicheaux frequently goes out to bat for black people in and around New Iberia, Louisiana. Robicheaux’s ghosts are, even when he is sober, usually that of Confederate soldiers who haunt his neighbourhood swamps and bayous. I find this an interesting slant because where John Connolly’s Louis will wreak havoc on a person who happens to have the temerity to sport a Confederate pennant on his car aerial, Robicheaux’s relationship with his CSA spectres is much more subtle.

urke’s Louisiana is both intensely poetic and deeply political. In Robicheaux: You Know My Name he writes:

urke’s Louisiana is both intensely poetic and deeply political. In Robicheaux: You Know My Name he writes: Elsewhere his rage at his own government’s insipid reaction to the devastation of Hurricane Katrina rivals his fury at generations of white people who have bled the life and soul out of the black and Creole population of the Louisian/Texas coastal regions. Sometimes the music he hears is literal, like in Jolie Blon’s Bounce (2002), but at other times it is sombre requiem that only he can hear:

Elsewhere his rage at his own government’s insipid reaction to the devastation of Hurricane Katrina rivals his fury at generations of white people who have bled the life and soul out of the black and Creole population of the Louisian/Texas coastal regions. Sometimes the music he hears is literal, like in Jolie Blon’s Bounce (2002), but at other times it is sombre requiem that only he can hear: