ack in the day, before authors and their publishers trusted me with reviewing novels, I did what the vast majority of the reading public did – I either bought books when I could afford them or I went to the local library. I had a list of authors whose latest works I would grab eagerly, or take my place in the queue of library members who had reserved copies. In no particular order, anything by John Connolly, Jim Kelly, Phil Rickman, Frank Tallis, Philip Kerr, Mark Billingham, Christopher Fowler and Nick Oldham would be like gold dust.

ack in the day, before authors and their publishers trusted me with reviewing novels, I did what the vast majority of the reading public did – I either bought books when I could afford them or I went to the local library. I had a list of authors whose latest works I would grab eagerly, or take my place in the queue of library members who had reserved copies. In no particular order, anything by John Connolly, Jim Kelly, Phil Rickman, Frank Tallis, Philip Kerr, Mark Billingham, Christopher Fowler and Nick Oldham would be like gold dust.

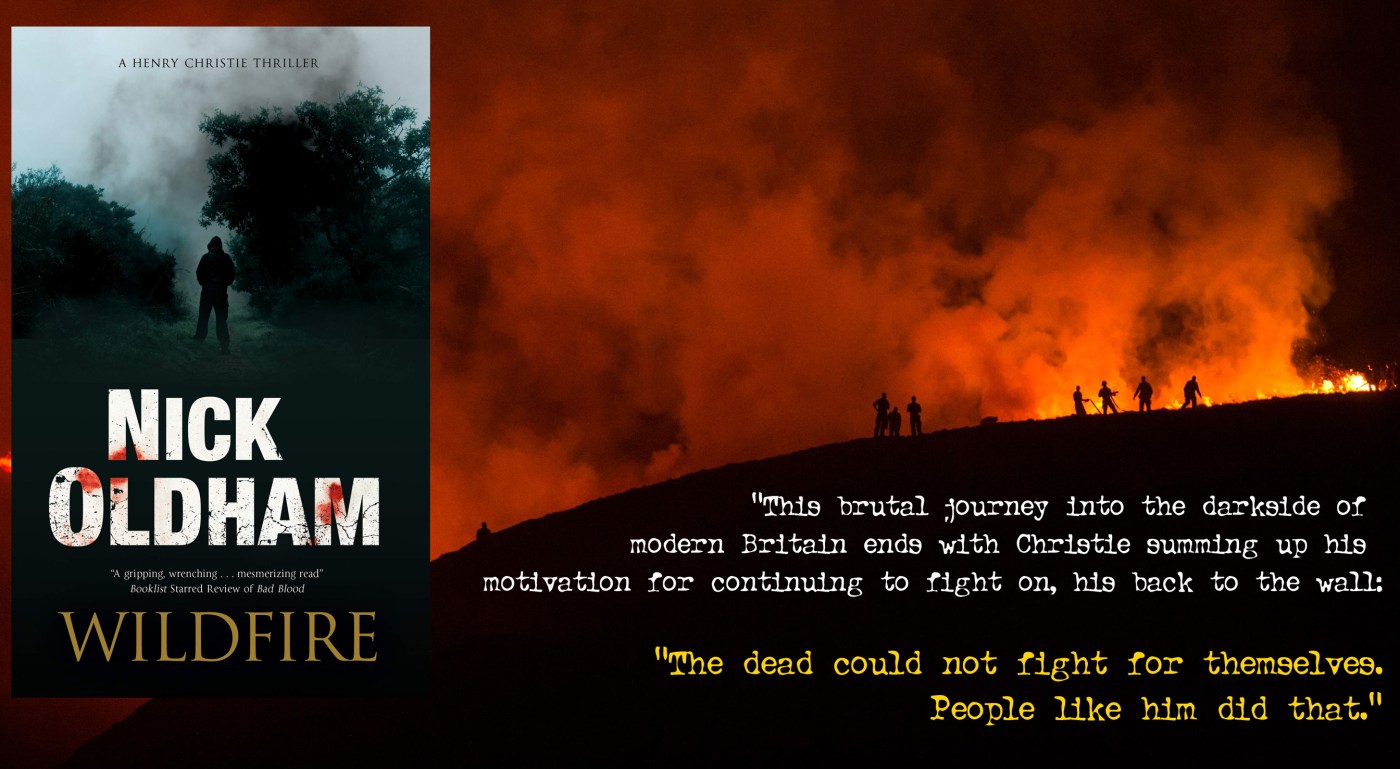

Oldham’s Henry Christie was a particular favourite, as his adventures mixed excellent police procedure – thanks to Oldham’s career as a copper – a vulnerable and likeable hero, and an unflinching look at the mean and vicious streets of the Blackpool area in England’s north-west. Wildfire is the latest outing for Henry Christie, who has retired from the police and now runs a pleasant village pub set in the Lancashire hills.

Oldham’s Henry Christie was a particular favourite, as his adventures mixed excellent police procedure – thanks to Oldham’s career as a copper – a vulnerable and likeable hero, and an unflinching look at the mean and vicious streets of the Blackpool area in England’s north-west. Wildfire is the latest outing for Henry Christie, who has retired from the police and now runs a pleasant village pub set in the Lancashire hills.

The book’s title works both literally and as a metaphor: the moorland around Kendleton, where Christie pulls pints in The Tawny Owl is on fire, the gorse and heather tinder dry and instantly combustible. People in farms and cottages on the moors have been advised to evacuate, and The Tawny Owl has become a refreshment station, serving bacon butties and hot tea to exhausted firefighters. The violence of nature is being faithfully echoed, however, by human misdeeds. A gang of particularly lawless and well-organised Travellers* has targeted a money-laundering operation based in an isolated former farm. The body count is rising, and the sums of money involved are simply eye-watering, as Christie is asked to join the police investigation as a consultant.

When Christie visits a refurbished ‘nick’ he finds that little has changed:

“…the complex was already beginning to reek of the bitter smell of men in custody: a combination of sweat, urine, alcohol, shit, general body odour and a dash of fear. Even new paint could not suppress it.”

D.C. Diane Daniels, Christie’s police ‘minder’ has driven him to a lawless Blackpool estate, once known as Shoreside, but rechristened Beacon View by some hopelessly optimistic council committee:

“Money had been chucked at it occasionally, usually to build children’s play areas, but each one had been systematically demolished by uncontrollable youths. Council houses had been abandoned, trashed, then knocked down. A row of shops had been brought down brick by brick, with the exception of the end shop – a grocer/newsagent that survived only because its proprietor handled stolen goods.”

The locals don’t take kindly to their visit and Daniels tries to drive her battered Peugot away from trouble:

“Ahead of her, spread out across the avenue and blocking their exit, was a group of about a dozen youths, male and female, plus a couple of pitbull-type dogs on thick chains, The youth’s faces were covered in scarves and in their hands they bounced hunks of house brick or stone; one had an iron bar like a jemmy.”

ventually, the wildfires of both kinds are extinguished, at least temporarily, but not before Henry Christie is forced, yet again, to take a long hard look at himself in the mirror, and question if it was all worth the effort.

ventually, the wildfires of both kinds are extinguished, at least temporarily, but not before Henry Christie is forced, yet again, to take a long hard look at himself in the mirror, and question if it was all worth the effort.

There is a complete absence of fuss and pretension about Oldham’s writing. Dismiss him at your peril, though, as just another writer of pot-boiler crime thrillers. He has created one of the most endearing – and enduring – heroes in contemporary fiction, and in his portrayal of a region not necessarily known for its criminality, he lifts a large stone to reveal several horrid things scuttling away from the unwanted light.

his brutal journey into the darkside of modern Britain ends with Christie summing up his motivation for continuing to fight on, his back to the wall:

his brutal journey into the darkside of modern Britain ends with Christie summing up his motivation for continuing to fight on, his back to the wall:

“The dead could not fight for themselves.People like him did that.”

Wildfire is published by Severn House and is available now.

March 1966. Cornell (right) was having a quiet drink in The Blind Beggar pub, well inside Kray territory on Whitechapel Road, when Ronnie walked in and put a bullet from a 9mm Luger into his head. Needless to say, none of the bar staff or other customers saw a single thing. Kray was eventually convicted of the murder when a barmaid, aware that Ronnie was already safely under lock and key for other misdeeds, testified that she had witnessed the killing.

March 1966. Cornell (right) was having a quiet drink in The Blind Beggar pub, well inside Kray territory on Whitechapel Road, when Ronnie walked in and put a bullet from a 9mm Luger into his head. Needless to say, none of the bar staff or other customers saw a single thing. Kray was eventually convicted of the murder when a barmaid, aware that Ronnie was already safely under lock and key for other misdeeds, testified that she had witnessed the killing.

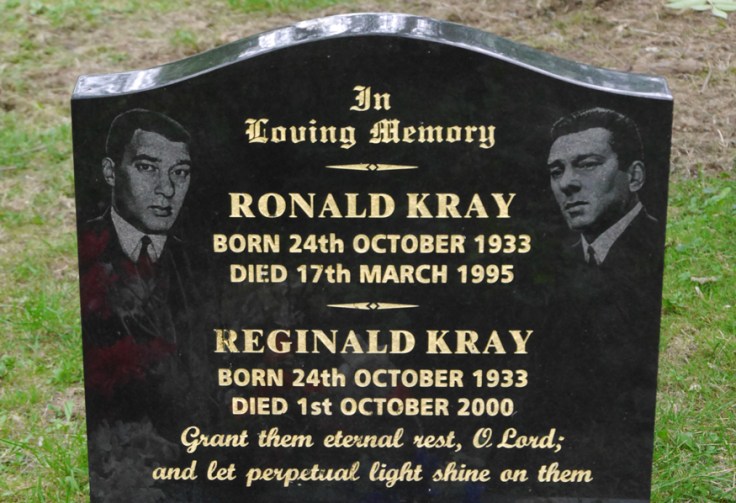

REGGIE AND RONNIE KRAY have been the subject of almost as many books, documentaries and dramas as their 19th century near-neighbour Jack the Ripper. The East End that he – whoever he was – knew has changed almost beyond recognition. The Bethnal Green of the Krays is heading in the same direction, but a few landmarks remain unscathed. They were born out in Hoxton in October 1933, Reggie being the older by ten minutes. The family moved into Bethnal Green in 1938, and they lived at 178 Vallance Road. That house no longer stands, modern houses having been built on the site (left)

REGGIE AND RONNIE KRAY have been the subject of almost as many books, documentaries and dramas as their 19th century near-neighbour Jack the Ripper. The East End that he – whoever he was – knew has changed almost beyond recognition. The Bethnal Green of the Krays is heading in the same direction, but a few landmarks remain unscathed. They were born out in Hoxton in October 1933, Reggie being the older by ten minutes. The family moved into Bethnal Green in 1938, and they lived at 178 Vallance Road. That house no longer stands, modern houses having been built on the site (left)

George Cornell (right) had known the twins from childhood. Their careers had developed more or less on similar lines, except that Cornell became the enforcer for the Richardsons. On 7th March 1966 there was a confused shoot-out at a club in Catford. Members of the Kray gang and the Richardsons gang were involved. At some point, George Cornell had been heard to refer to Ronnie Kray as a “fat poof.” That might seem unkind, but was not totally inaccurate. Ronnie was certainly plumper than his lean and hungry twin, and his liking for handsome boys was well known.

George Cornell (right) had known the twins from childhood. Their careers had developed more or less on similar lines, except that Cornell became the enforcer for the Richardsons. On 7th March 1966 there was a confused shoot-out at a club in Catford. Members of the Kray gang and the Richardsons gang were involved. At some point, George Cornell had been heard to refer to Ronnie Kray as a “fat poof.” That might seem unkind, but was not totally inaccurate. Ronnie was certainly plumper than his lean and hungry twin, and his liking for handsome boys was well known. On the evening of 9th March, Cornell and an associate were unwise enough to call in for a drink at a The Blind Beggar pub on Whitechapel Road, very much in Kray territory. Some thoughtful soul telephoned Ronnie Kray, who was drinking in a nearby pub, The Lion in Tapp Street (left). Ronnie, pausing only to collect a handgun made straight for the Blind Beggar, strode in, and shot George Cornell in the head at close range. His death was almost instantaneous. Needless to say, no-one else in the pub had seen anything. Pictured below are a post mortem photograph of Cornell, and the bloodstained floor of The Blind Beggar. Below that is the fatal pub, then and now.

On the evening of 9th March, Cornell and an associate were unwise enough to call in for a drink at a The Blind Beggar pub on Whitechapel Road, very much in Kray territory. Some thoughtful soul telephoned Ronnie Kray, who was drinking in a nearby pub, The Lion in Tapp Street (left). Ronnie, pausing only to collect a handgun made straight for the Blind Beggar, strode in, and shot George Cornell in the head at close range. His death was almost instantaneous. Needless to say, no-one else in the pub had seen anything. Pictured below are a post mortem photograph of Cornell, and the bloodstained floor of The Blind Beggar. Below that is the fatal pub, then and now.

Folklore has it that now that Ronnie had ‘done the big one’, there was pressure on Reggie to match his twin’s achievement. The chance was over a year in coming. Jack McVitie (right) was a drug addicted criminal enforcer who worked, on and off, for the Krays. His nickname ‘The Hat’ was because he was embarrassed about his thinning hair, and always wore a trademark trilby. McVitie had taken £500 from the Krays to kill someone, had botched the job, but kept the money. He had also, unwisely,been heard to bad-mouth the twins.

Folklore has it that now that Ronnie had ‘done the big one’, there was pressure on Reggie to match his twin’s achievement. The chance was over a year in coming. Jack McVitie (right) was a drug addicted criminal enforcer who worked, on and off, for the Krays. His nickname ‘The Hat’ was because he was embarrassed about his thinning hair, and always wore a trademark trilby. McVitie had taken £500 from the Krays to kill someone, had botched the job, but kept the money. He had also, unwisely,been heard to bad-mouth the twins. On the night of 29th October 1967, McVitie was lured to a basement flat in Evering Road, Stoke Newington,(left) on the pretext of a party. There, he was met by Reggie Kray and other members of the firm. Kray’s attempt to shoot McVitie misfired – literally – and instead, he stabbed McVitie repeatedly with a carving knife. McVitie’s body was never found, and the stories about his eventual resting place range from his being fed to the fishes of the Sussex coast to being buried incognito in a Gravesend cemetery.

On the night of 29th October 1967, McVitie was lured to a basement flat in Evering Road, Stoke Newington,(left) on the pretext of a party. There, he was met by Reggie Kray and other members of the firm. Kray’s attempt to shoot McVitie misfired – literally – and instead, he stabbed McVitie repeatedly with a carving knife. McVitie’s body was never found, and the stories about his eventual resting place range from his being fed to the fishes of the Sussex coast to being buried incognito in a Gravesend cemetery.