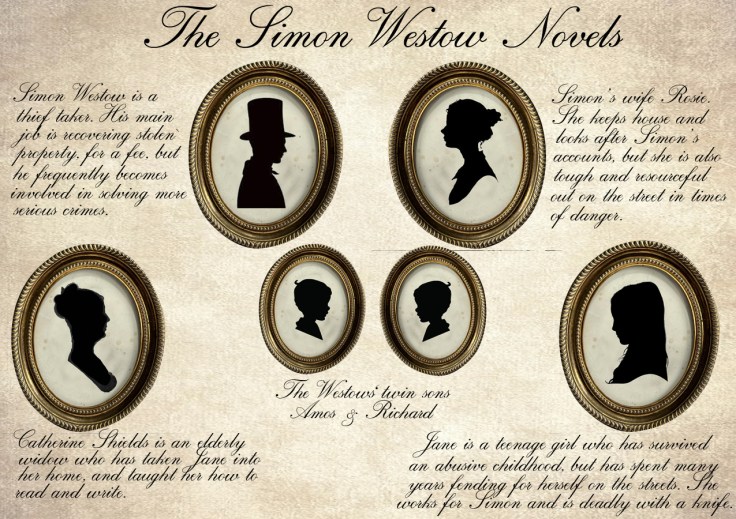

Leeds, Autumn 1824. Simon Westow is engaged by a retired military man, Captain Holcomb, to recover some papers which have been stolen from his house. They concern the career of his father, a notoriously hard-line magistrate. Newcomers to the series may find this graphic helpful to establish who is who.

Westow takes the job, but is concerned when Holcomb refuses to reveal what might be in the missing papers, thus preventing the thief taker from narrowing down a list of suspects. As is often the case in this excellent series, what begins as case of simple theft turns much darker when murder raises its viler and misshapen head.

Jane, Westow’s sometime assistant, has taken a step back from the work as, under the kind attention of Catherine Shields, she is learning that there is a world outside the dark streets she used to inhabit. The lure of books and education is markedly different from the law of the knife, and a life spent lurking in shadowy alleys. Nevertheless, she agrees to come back to help Westow with his latest case, which has turned sour. When Westow, suspecting there is more to the case than meets the eye, refuses to continue looking for the missing documents, Holcomb threatens to sue him and ruin his reputation.

More or less by accident, Westow and Jane have uncovered a dreadful series of crimes which may connected to the Holcomb documents. Young girls – and it seems the younger the better – have been abducted for the pleasure of certain wealth and powerful ‘gentlemen’. Jane, galvanised by her own bitter memories of being sexually abused by her father, meets another youngster from the streets, Sally.

Sally is a mirror image of Jane in her younger days – street-smart, unafraid of violence, and an expert at wielding a viciously honed knife. Jane hesitates in recruiting the child to a way of life she wishes to move away from, but the men involved in the child abuse must be brought down, and Sally’s apparent innocence is a powerful weapon.

As ever in Nickson’s Leeds novels, whether they be these, the Victorian era Tom Harper stories, or those set in the 1940s and 50s, the city itself is a potent force in the narrative. The contrast between the grinding poverty of the underclass – barely surviving in their insanitary slums – and the growing wealth of the merchants and factory owners could not be starker. The paradox is not just a human one. The River Aire is the artery which keeps the city’s heart beating, but as it flows past the mills and factories, it is coloured by the poison they produce. Yet, at Kirkstall, where it passes the stately ruins of the Abbey it is still – at least in the 1820s – a pure stream home to trout and grayling. Just an hour’s walk from Westow’s beat, there are moors, larks high above, and air unsullied by sulphur and the smoke of foundry furnaces.

The scourge of paedophilia is not something regularly used as subject matter in crime fiction, perhaps because it is – and this is my personal view – if not the worst of all crimes, then at least as bad as murder. Yes, the victims that survive may still live and breathe, but their innocence has been ripped away and, in its place, has been implanted a mental and spiritual tumour for which there is no treatment. Two little girls are rescued by Westow, Jane and Sally and are restored to their parents, but what living nightmares await them in the years to come we will never know.

I have come to admire Nickson’s passion for his city and its history, and his skill at making characters live and breathe is second to none, but in this powerful and haunting novel he reminds us that we are only ever a couple of steps from the abyss. The Scream of Sins will be published by Severn House on 5th March.

I’m a great fan of historical crime fiction, particularly if it is set in the 19th or 20th centuries, but I will be the first to admit that most such novels tend not to veer towards what I call The Dark Side. Perhaps it’s the necessary wealth of period detail which gets in the way, and while some writers revel in the more lurid aspects of poverty, punishment and general mortality, the genre is usually a long way from noir. That’s absolutely fine. Many noir enthusiasts (noiristes, perhaps?) avoid historical crime in the same way that lovers of a good period yarn aren’t drawn to existential world of shadows cast by flickering neon signs on wet pavements. The latest novel from RN Morris, The White Feather Killer is an exception to my sweeping generalisation, as it is as uncomfortable and haunting a tale as I have read for some time.

I’m a great fan of historical crime fiction, particularly if it is set in the 19th or 20th centuries, but I will be the first to admit that most such novels tend not to veer towards what I call The Dark Side. Perhaps it’s the necessary wealth of period detail which gets in the way, and while some writers revel in the more lurid aspects of poverty, punishment and general mortality, the genre is usually a long way from noir. That’s absolutely fine. Many noir enthusiasts (noiristes, perhaps?) avoid historical crime in the same way that lovers of a good period yarn aren’t drawn to existential world of shadows cast by flickering neon signs on wet pavements. The latest novel from RN Morris, The White Feather Killer is an exception to my sweeping generalisation, as it is as uncomfortable and haunting a tale as I have read for some time. orris takes his time before giving us a dead body, but his drama has some intriguing characters. We met Felix Simpkins, such a mother’s boy that, were he to be realised on the screen, we would have to resurrect Anthony Perkins for the job. His mother is not embalmed in the apple cellar, but an embittered and waspish German widow, a failed concert pianist, a failed wife, and a failed pretty much everything else except in the dubious skill of humiliating her hapless son. Central to the grim narrative is the Cardew family. Baptist Pastor Clement Cardew is the head of the family; his wife Esme knows her place, but his twin children Adam and Eve have a pivotal role in what unfolds. The trope of the hypocritical and venal clergyman is well-worn but still powerful; when we realise the depth of Cardew’s descent into darkness, it is truly chilling.

orris takes his time before giving us a dead body, but his drama has some intriguing characters. We met Felix Simpkins, such a mother’s boy that, were he to be realised on the screen, we would have to resurrect Anthony Perkins for the job. His mother is not embalmed in the apple cellar, but an embittered and waspish German widow, a failed concert pianist, a failed wife, and a failed pretty much everything else except in the dubious skill of humiliating her hapless son. Central to the grim narrative is the Cardew family. Baptist Pastor Clement Cardew is the head of the family; his wife Esme knows her place, but his twin children Adam and Eve have a pivotal role in what unfolds. The trope of the hypocritical and venal clergyman is well-worn but still powerful; when we realise the depth of Cardew’s descent into darkness, it is truly chilling. Historical novels come and go, and all too many are over-reliant on competent research and authentic period detail, but Morris (right) plays his ace with his brilliant and evocative use of language. Here, Quinn watches, bemused, as a company of army cyclists spin past him:

Historical novels come and go, and all too many are over-reliant on competent research and authentic period detail, but Morris (right) plays his ace with his brilliant and evocative use of language. Here, Quinn watches, bemused, as a company of army cyclists spin past him: uinn has to pursue his enquiries in one of the quieter London suburbs, and makes this wry observation of the world of Mr Pooter – quaintly comic, but about to be shattered by events:

uinn has to pursue his enquiries in one of the quieter London suburbs, and makes this wry observation of the world of Mr Pooter – quaintly comic, but about to be shattered by events:

There is, however, that strange smell. A certain je ne sais quoi which will not go away, despite the couple’s best efforts. When Jack finally plucks up the courage to climb up into the roof space, he finds the physical source of the smell but unpleasant as that is, he also finds something which is much more disturbing. Simon Lelic (right) then has us walking on pins and needles as he unwraps a plot which involves obsession, child abuse, psychological torture and plain old-fashioned violence.

There is, however, that strange smell. A certain je ne sais quoi which will not go away, despite the couple’s best efforts. When Jack finally plucks up the courage to climb up into the roof space, he finds the physical source of the smell but unpleasant as that is, he also finds something which is much more disturbing. Simon Lelic (right) then has us walking on pins and needles as he unwraps a plot which involves obsession, child abuse, psychological torture and plain old-fashioned violence.