Detective Sergeant George Cross is unique among fictional British coppers in that he is autistic. This apparent disability gives him singular powers when investigating crimes. While totally unaware of social nuances, his analytical mind stores and organises information in a manner denied to more ‘normal’ colleagues within the Bristol police force. When questioning suspects or witness his completely literal mindset can be disconcerting to both guilty and innocent alike. Regular visitors to the site may remember that I reviewed two earlier novels in the series The Monk (2023) and The Teacher (2024) but, for new readers, this is the background. Cross is in his forties, balding, of medium height and, in appearance no-one’s idea of a policeman, fictional or otherwise. He lives alone in his flat, cycles to work, and likes to play the organ in a nearby Roman Catholic Church, where he is friends with the priest. George’s elderly father lives nearby, but his mother left the family home when George was five. At the time he was unaware that she left because Raymond Cross was homosexual. Now, Christine, has slowly reintroduced herself into the family group and George, reluctantly, has come to accept her presence.

This case begins when an elderly bookseller, Torquil Squire returns to his flat above the shop after a day out at an antiquarian book sale at Sothebys. He is horrified to find his son Ed, who is the day-to-day manager of the shop, dead on the floor, stabbed in the chest. George and his fellow DS Josie Ottey head up the investigation which is nominally led by their ineffectual boss DCI Ben Carson.P.The world of rare and ancient books does not immediately suggest itself to George as one where violent death is a common occurrence, but he soon learns that despite the artefacts being valued in mere millions rather than the billions involved in, say, corporate fraud, there are still jealousies, bitter rivalries and long running feuds. One such is the long running dispute between Ed Squire and a prestigious London firm Carnegies, who Ed believed were instrumental in creating a dealership ring, whereby prominent sellers formed a cartel to buy up all available first editions of important novels, thus being able to control – and inflate – prices to their mutual advantage.

Then there is the mysterious Russian oligarch, an avid collector of books and manuscripts, who paid Ed a sizeable commission to buy a set of fifteenth century letters written by Christopher Columbus, only for the oligarch to discover that the letters had, in fact, been stolen from an American museum. Could Oleg Dimitriev have resorted to Putinesque methods following the debacle?

Running parallel to the murder investigation is a crisis in George’s own life. Raymond discovers that he has lung cancer, but it operable. During the operation, however, he suffers a stroke. When he is well enough to return home he faces a long and difficult period of recuperation and therapy for which George is ready and able to organise. More of a problem for him, however, is the challenge to his limited emotional capacity to deal with the conventionally expected responses. Even before his father’s illness, George has been disconcerted to learn that Josie Ottey has been promoted to Detective Inspector, and he finds it difficult to adjust to what he perceives as a dramatic change in their relationship.

The killer of Ed Squire is, of course, identified and brought to justice, but not before we have been led down many a garden path by Tim Sullivan. The Bookseller is thoughtful and entertaining, with enough darker moments to lift it above the run-of-the-mill procedural. Published by Head of Zeus, it is available now.

Every schoolboy of my generation was taught the history of Britain’s great social reformers of the 19th century, and we were able to rattle off their names – Elizabeth Fry for prisons, Florence Nightingale for nursing, Cobbett for agriculture and Wilberforce for slavery. I have to confess that until I moved to Wisbech in the early 1990s, I hadn’t heard of Thomas Clarkson. Now, as I pass his imposing memorial every time I walk into town it is a constant reminder of a man who has been called ‘the moral steam engine’ of the movement to end Britain’s connection to the slave trade.

Every schoolboy of my generation was taught the history of Britain’s great social reformers of the 19th century, and we were able to rattle off their names – Elizabeth Fry for prisons, Florence Nightingale for nursing, Cobbett for agriculture and Wilberforce for slavery. I have to confess that until I moved to Wisbech in the early 1990s, I hadn’t heard of Thomas Clarkson. Now, as I pass his imposing memorial every time I walk into town it is a constant reminder of a man who has been called ‘the moral steam engine’ of the movement to end Britain’s connection to the slave trade.

Clarkson narrowly avoids becoming the victim of a mob in Liverpool. Meanwhile, as readers, we are privy to Dr Gardner’s diary written during the voyage of The Brothers. The two narratives become parallel: at sea, once the slaves have been offloaded, the voyage of the vessel – in theory a relatively safe and simple return home – is blighted by what seems to be a malignant spirit at work in the depths of the ship. The crew members disappear, one by one, and the barbarous Captain Howlett is driven mad.

Clarkson narrowly avoids becoming the victim of a mob in Liverpool. Meanwhile, as readers, we are privy to Dr Gardner’s diary written during the voyage of The Brothers. The two narratives become parallel: at sea, once the slaves have been offloaded, the voyage of the vessel – in theory a relatively safe and simple return home – is blighted by what seems to be a malignant spirit at work in the depths of the ship. The crew members disappear, one by one, and the barbarous Captain Howlett is driven mad.

Watching You by Lisa Jewell takes us to the chic urban village of Melville Heights. Jack Mullen is a successful consultant in cardiology, while his wife Rebecca is “something in systems analysis.” A couple of doors down live the Fitzwilliam family. Tom is a charismatic and nationally renowned Head Teacher with an impressive record of turning round failing high schools. His adoring wife Nicola has no CV as such, unless you want to list an over-awareness of body image and a devotion to the latest fads in fashion and diet. Their teenage son, Freddie – an only child, naturally – is very keen on all things technical, particularly digital binoculars, spy software, and a fascination with the lives and movements of anyone he can see from his bedroom window.

Watching You by Lisa Jewell takes us to the chic urban village of Melville Heights. Jack Mullen is a successful consultant in cardiology, while his wife Rebecca is “something in systems analysis.” A couple of doors down live the Fitzwilliam family. Tom is a charismatic and nationally renowned Head Teacher with an impressive record of turning round failing high schools. His adoring wife Nicola has no CV as such, unless you want to list an over-awareness of body image and a devotion to the latest fads in fashion and diet. Their teenage son, Freddie – an only child, naturally – is very keen on all things technical, particularly digital binoculars, spy software, and a fascination with the lives and movements of anyone he can see from his bedroom window. This is a clever, clever murder mystery. Lisa Jewell gives us the corpse right at the beginning – while keeping us guessing about whose it is – and then, by shrewd manipulation of the timeline we are introduced to the possible perpetrators of the violent death. By page 100, they have formed an orderly queue for our attention. Of course there’s beautiful, feckless Joey and her husband Alfie. Freddie Fitzwilliam is clearly at the sharp end of the Asperger spectrum, but what about his bird-like – and bird-brained mother? Schoolgirls Jenna and Bess are clearly fixated – for different reasons – on their headteacher, and as for Jenna’s mum, with her persecution complex and incipient madness, she is clearly on the brink of doing something destructive, either to herself or someone else. And who is the mysterious woman who flew into a rage with Tom ten years earlier while the Fitzwilliams were on a family holiday to the Lake District?

This is a clever, clever murder mystery. Lisa Jewell gives us the corpse right at the beginning – while keeping us guessing about whose it is – and then, by shrewd manipulation of the timeline we are introduced to the possible perpetrators of the violent death. By page 100, they have formed an orderly queue for our attention. Of course there’s beautiful, feckless Joey and her husband Alfie. Freddie Fitzwilliam is clearly at the sharp end of the Asperger spectrum, but what about his bird-like – and bird-brained mother? Schoolgirls Jenna and Bess are clearly fixated – for different reasons – on their headteacher, and as for Jenna’s mum, with her persecution complex and incipient madness, she is clearly on the brink of doing something destructive, either to herself or someone else. And who is the mysterious woman who flew into a rage with Tom ten years earlier while the Fitzwilliams were on a family holiday to the Lake District? Lisa Jewell peels away veil after veil, but like Salome in front of Herod, she tantalises us with exquisite cruelty. Just when we think we have understood the truth about the complex relationships between the characters, we are faced with another enigma and a further conundrum. There are flashes of absolute brilliance throughout this gripping novel. The relationship between Jenna and Bess is beautifully described and even though we suspect he may end up with blood on his hands, Freddie’s strange but exotic view of the world around him makes him completely appealing. In the end, of course,we learn the identity of the corpse and that of the murderer but, just like the Pinball Wizard, there has got to be a twist. Lisa Jewell (left) provides it with the last 39 words of this very special book, and it is not so much a twist as a breathtaking literary flourish.

Lisa Jewell peels away veil after veil, but like Salome in front of Herod, she tantalises us with exquisite cruelty. Just when we think we have understood the truth about the complex relationships between the characters, we are faced with another enigma and a further conundrum. There are flashes of absolute brilliance throughout this gripping novel. The relationship between Jenna and Bess is beautifully described and even though we suspect he may end up with blood on his hands, Freddie’s strange but exotic view of the world around him makes him completely appealing. In the end, of course,we learn the identity of the corpse and that of the murderer but, just like the Pinball Wizard, there has got to be a twist. Lisa Jewell (left) provides it with the last 39 words of this very special book, and it is not so much a twist as a breathtaking literary flourish.

When the battered body of teenager Melanie Cooke is found amid the garbage bins in a seedy Bristol alleyway, it is obvious that she has been murdered. Only fourteen, she is dressed in the kind of clothes which would be considered provocative on a woman twice her age. Vogel goes to make the dreaded ‘death call’, but he only has to appear on the doorstep of the girl’s home for her mother and father to sense the worst. Like many rebellious teenagers before her, Melanie has told her parents that she is going round to a mate’s house to do some homework. When she failed to come home, their first ‘phone call confirmed Melanie’s lie, and thereafter, the long dark hours of the night are spent in increasing anxiety and then terror, as they realise that something awful has happened.

When the battered body of teenager Melanie Cooke is found amid the garbage bins in a seedy Bristol alleyway, it is obvious that she has been murdered. Only fourteen, she is dressed in the kind of clothes which would be considered provocative on a woman twice her age. Vogel goes to make the dreaded ‘death call’, but he only has to appear on the doorstep of the girl’s home for her mother and father to sense the worst. Like many rebellious teenagers before her, Melanie has told her parents that she is going round to a mate’s house to do some homework. When she failed to come home, their first ‘phone call confirmed Melanie’s lie, and thereafter, the long dark hours of the night are spent in increasing anxiety and then terror, as they realise that something awful has happened. The book actually starts with a prologue which at first glance appears to be nothing to do with Melanie’s death. It is only later – much later – that we learn its true significance. Bonner (right) is determined not to give us a straightforward narrative. The progress of Vogel’s attempts to find Melanie’s killer are sandwiched between accounts from three different men, each of whom is living a life where all is not as it seems.

The book actually starts with a prologue which at first glance appears to be nothing to do with Melanie’s death. It is only later – much later – that we learn its true significance. Bonner (right) is determined not to give us a straightforward narrative. The progress of Vogel’s attempts to find Melanie’s killer are sandwiched between accounts from three different men, each of whom is living a life where all is not as it seems.

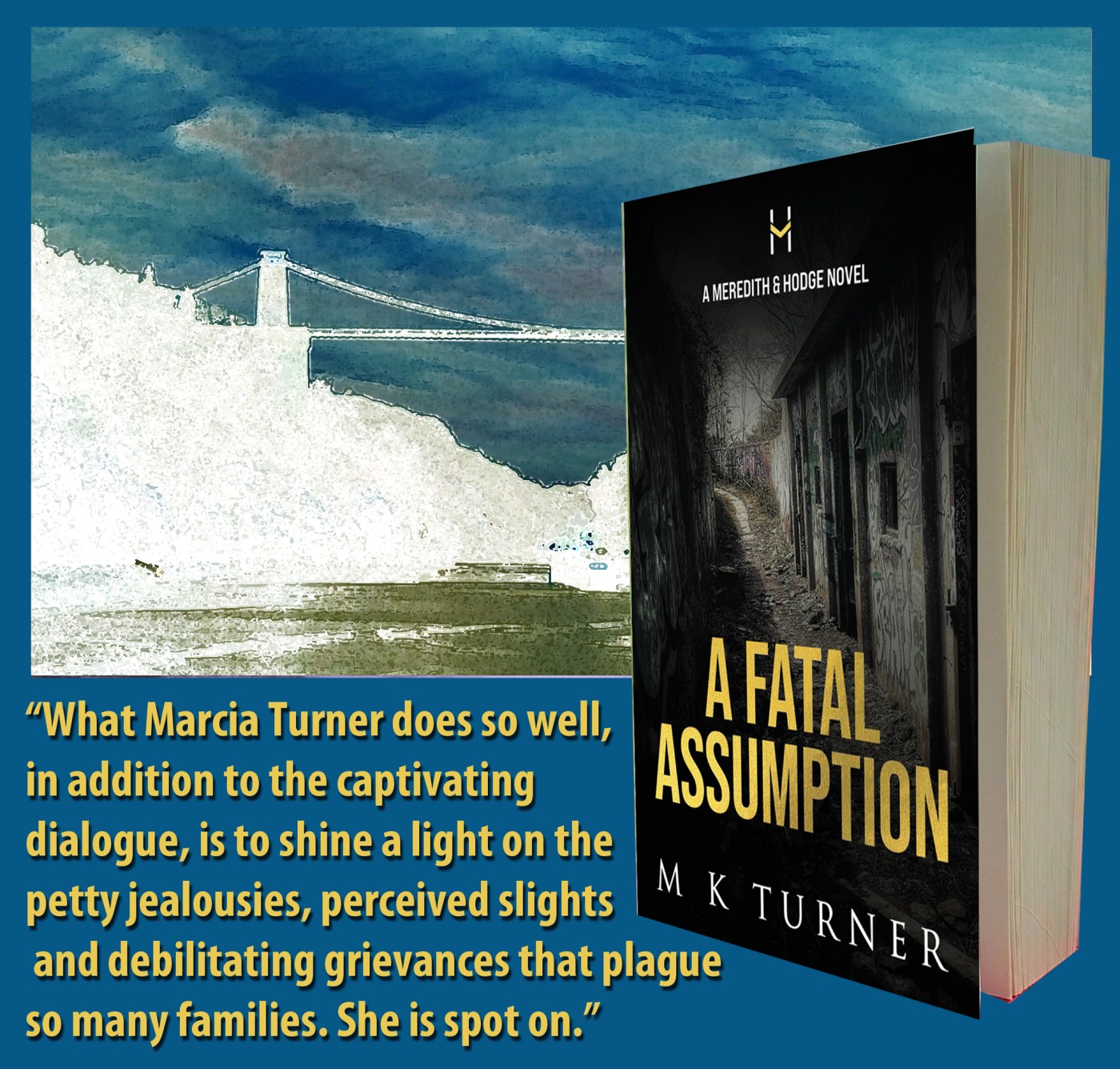

Back in late 2016, I had the pleasure of listening to T A Cotterell read an extract from his debut novel, What Alice Knew. He made it clear that this was a book about secrets, and about that strange beast, family life. Family life. The words are anodyne, mild and reassuring, but we all know that many families are not what they seem to be to an outsider. Cotterell’s question, though, is simply this: “How well do members of a family know each other?”

Back in late 2016, I had the pleasure of listening to T A Cotterell read an extract from his debut novel, What Alice Knew. He made it clear that this was a book about secrets, and about that strange beast, family life. Family life. The words are anodyne, mild and reassuring, but we all know that many families are not what they seem to be to an outsider. Cotterell’s question, though, is simply this: “How well do members of a family know each other?” From this point on, the dreamy soft-focus life of the Sheahan family descends into a nightmare reality, all jagged edges and harshly grating contrasts. The visual metaphor is actually totally appropriate, as one of the great strengths of the novel is how Alice sees much of life through her painterly eyes. Rose madder, cadmium yellow, viridian, alizarin crimson and flake white. Alice’s world is the world of the quaintly named oil paints on her palette. It came as no surprise to me to learn that Cotterell (right) studied History of Art at Cambridge.

From this point on, the dreamy soft-focus life of the Sheahan family descends into a nightmare reality, all jagged edges and harshly grating contrasts. The visual metaphor is actually totally appropriate, as one of the great strengths of the novel is how Alice sees much of life through her painterly eyes. Rose madder, cadmium yellow, viridian, alizarin crimson and flake white. Alice’s world is the world of the quaintly named oil paints on her palette. It came as no surprise to me to learn that Cotterell (right) studied History of Art at Cambridge.