Historian and broadcaster Tony McMahon (left) sets out his stall in this book, and he is selling a provocative premise. It is that a celebrity fraudster, predatory homosexual, quack doctor and narcissist – Francis Tumblety – was instrumental in two of the greatest murder cases of the 19th century.The first was the assassination of Abraham Lincoln in April 1865, and the second was the murder of five women in the East End of London in the autumn of 1888 – the Jack the Ripper killings.

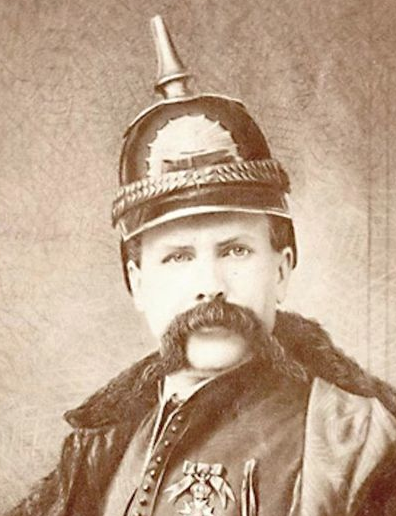

Tumblety was certainly larger than life. Tall and imposingly built, he favoured dressing up as a kind of Ruritanian cavalry officer, with a pickelhaub helmet, and sporting an immense handlebar moustache. He made – and lost – fortunes with amazing regularity, mostly by selling herbal potions to gullible patrons. Despite his outrageous behaviour, he does not seem to have been a violent man. Yes, he could have been accused of manslaughter after people died from ingesting his elixirs, but apart from once literally booting a disgruntled customer out of his suite, there is no record of extreme physical violence.

Historian and broadcaster Tony McMahon (left) sets out his stall in this book, and he is selling a provocative premise. It is that a celebrity fraudster, predatory homosexual, quack doctor and narcissist – Francis Tumblety – was instrumental in two of the greatest murder cases of the 19th century.The first was the assassination of Abraham Lincoln in April 1865, and the second was the murder of five women in the East End of London in the autumn of 1888 – the Jack the Ripper killings.

Tumblety was certainly larger than life. Tall and imposingly built, he favoured dressing up as a kind of Ruritanian cavalry officer, with a pickelhaub helmet, and sporting an immense handlebar moustache. He made – and lost – fortunes with amazing regularity, mostly by selling herbal potions to gullible patrons. Despite his outrageous behaviour, he does not seem to have been a violent man. Yes, he could have been accused of manslaughter after people died from ingesting his elixirs, but apart from once literally booting a disgruntled customer out of his suite, there is no record of extreme physical violence.

Lincoln’s killer John Wilkes Booth and David Herold, a rather dimwitted youth who, along with Mary Suratt and George Azerodt, was hanged for his part in the conspiracy, were certainly known to Tumblety, although there is little evidence that he shared Booth’s Confederate zealotry. Tumblety does not come across as a particularly political animal, although McMahon makes the point that he had friends in high places, who provided him with a ‘get out of jail free’ card on the many occasions when he found himself in court.

Tumblety (right( was a braggart, a charlatan, a narcissist and a predatory homosexual abuser of young men. Tony McMahon makes this abundantly clear with his exhaustive historical research. What the book doesn’t do, despite it being a thrilling read, is explain why the obnoxious Tumblety made the leap from being what we would call a bull***t artist to the person who killed five women in the autumn of 1888, culminating in the butchery that ended of the life Mary Jeanette Kelly in her Miller’s Court room on the 9th November. Her injuries were horrific, and the details are out there should you wish to look for them. As for Lincoln’s homosexuality – and his syphilis – the jury has been out for some time, with little sign that they will be returning any time soon. McMahon is absolutely correct to say that syphilis was a mass killer. My great grandfather’s death certificate states that he died, aged 48, of General Paralysis of the Insane. Also known as Paresis, this was a euphemistic term for tertiary syphilis. The disease would be contracted in relative youth, produce obvious physical symptoms, and then seem to disappear. Later in life, it would manifest itself in mental incapacity, delusions of grandeur, and physical disability. Lincoln was 56 when he was murdered and, as far as we know, in full command of his senses. I suggest that were Lincoln syphilitic, he would have been unable to maintain his public persona as it appears that he did.

Tumblety (right( was a braggart, a charlatan, a narcissist and a predatory homosexual abuser of young men. Tony McMahon makes this abundantly clear with his exhaustive historical research. What the book doesn’t do, despite it being a thrilling read, is explain why the obnoxious Tumblety made the leap from being what we would call a bull***t artist to the person who killed five women in the autumn of 1888, culminating in the butchery that ended of the life Mary Jeanette Kelly in her Miller’s Court room on the 9th November. Her injuries were horrific, and the details are out there should you wish to look for them. As for Lincoln’s homosexuality – and his syphilis – the jury has been out for some time, with little sign that they will be returning any time soon. McMahon is absolutely correct to say that syphilis was a mass killer. My great grandfather’s death certificate states that he died, aged 48, of General Paralysis of the Insane. Also known as Paresis, this was a euphemistic term for tertiary syphilis. The disease would be contracted in relative youth, produce obvious physical symptoms, and then seem to disappear. Later in life, it would manifest itself in mental incapacity, delusions of grandeur, and physical disability. Lincoln was 56 when he was murdered and, as far as we know, in full command of his senses. I suggest that were Lincoln syphilitic, he would have been unable to maintain his public persona as it appears that he did.

Is Tumblety a credible Ripper suspect? No more and no less than a dozen others. Yes, he was in London when the five canonical murders were committed, but so were, in no particular order, the Duke of Clarence, Neill Cream, Aaron Kosinski, Robert Stephenson, Walter Sickert and Michael Ostrog. Much is made of the fact that Tumblety left the country in some haste, catching a boat across The Channel to Le Havre, and then back to America. He certainly had been in police custody, but for acts of public indecency, and was released on bail, which suggests that the London police did not think he was a danger to the public. The fact is that we will never know. The killings during ‘ The Autumn of Terror’ will forever remain unsolved. At some point, I suppose, the murders will fade into forgetfulness, and books advocating the latest theory will no longer have a market.

The theory that Tumblety also suffered from syphilis could account for the insane rage with which Marie Jeanette Kelly was butchered, but we must bear in mind that Tumblety lived until he was 70, dying in St Louis in May 1903, apparently from a heart attack. This said, Tony McMahon has written a wonderfully entertaining book with an excellent narrative drive, and a jaw-dropping insight into the demi-monde of mid-19th century America. McMahon’s research is beyond question, and he provides extensive footnotes and very useful index. The cover blurb says, “One man links the two greatest crimes of the 19th century.” Tony McMahon establishes beyond dispute that Francis Tumblety was that man. Whether he proves that he was responsible for either is another matter altogether.

Quercus has just republished The Shot, a 1999 novel by Kerr. We are in America and it is the late autumn of 1960. In the pop charts, The Drifters were singing Save The Last Dance For Me, and a youthful looking senator called John Fitzgerald Kennedy had just won the election to become the thirty-fifth President of The United States.

Quercus has just republished The Shot, a 1999 novel by Kerr. We are in America and it is the late autumn of 1960. In the pop charts, The Drifters were singing Save The Last Dance For Me, and a youthful looking senator called John Fitzgerald Kennedy had just won the election to become the thirty-fifth President of The United States. As ever with a Philip Kerr novel, we are in a world populated by a mix of fictional characters and real-life figures. Among the latter are Jack Kennedy himself and the Mob boss Sam Giancana. Giancana hires Jefferson to assassinate Fidel Castro so that the revolution will collapse, and the mafioso can return to their old lucrative ways. Jefferson does his homework and seems all set to put a bullet in Castro’s head.

As ever with a Philip Kerr novel, we are in a world populated by a mix of fictional characters and real-life figures. Among the latter are Jack Kennedy himself and the Mob boss Sam Giancana. Giancana hires Jefferson to assassinate Fidel Castro so that the revolution will collapse, and the mafioso can return to their old lucrative ways. Jefferson does his homework and seems all set to put a bullet in Castro’s head.

Those last seven words kill, and journalist David Laws (left) has written a novel about the “passionate intensity” which sparks political assassination. The fateful day of Britain’s exit from the EU is dawning, and a vicious conspiracy is about to make all the previous months of political bickering seem like a garden party in comparison. Inadvertently, a journalist called Harry Topp has embedded himself at the heart of the plot, and he blunders on in search of a lifetime scoop, blissfully unaware of what is unfolding around him.

Those last seven words kill, and journalist David Laws (left) has written a novel about the “passionate intensity” which sparks political assassination. The fateful day of Britain’s exit from the EU is dawning, and a vicious conspiracy is about to make all the previous months of political bickering seem like a garden party in comparison. Inadvertently, a journalist called Harry Topp has embedded himself at the heart of the plot, and he blunders on in search of a lifetime scoop, blissfully unaware of what is unfolding around him.

London in 1967 seems to have been an exciting place to live. A play by a budding writer called Alan Aykbourne received its West End premier, Jimi Hendrix was setting fire to perfectly serviceable Fender Strats, The House of Commons passed the Sexual Offences Act decriminalising male homosexuality and Joe Orton and Kenneth Halliwell featured in a murder-suicide in their Islington flat. This is the backdrop as Hugh Fraser’s violent anti-heroine Rina Walker returns to her murderous ways in Stealth, the fourth novel of a successful series.

London in 1967 seems to have been an exciting place to live. A play by a budding writer called Alan Aykbourne received its West End premier, Jimi Hendrix was setting fire to perfectly serviceable Fender Strats, The House of Commons passed the Sexual Offences Act decriminalising male homosexuality and Joe Orton and Kenneth Halliwell featured in a murder-suicide in their Islington flat. This is the backdrop as Hugh Fraser’s violent anti-heroine Rina Walker returns to her murderous ways in Stealth, the fourth novel of a successful series.

Perhaps the world has shrunk, or maybe it is that organised crime, like politics, has gone global, but more recent British mobsters have become bigger and, because we can hardly say “better”, perhaps “more formidable” might be a better choice of words. No-one typifies this new breed of gang boss than John “Goldfinger” Palmer. His name is hardly on the tip of everyone’s tongues, but as this new book from Wensley Clarkson shows, Palmer’s misdeeds were epic and definitely world class.

Perhaps the world has shrunk, or maybe it is that organised crime, like politics, has gone global, but more recent British mobsters have become bigger and, because we can hardly say “better”, perhaps “more formidable” might be a better choice of words. No-one typifies this new breed of gang boss than John “Goldfinger” Palmer. His name is hardly on the tip of everyone’s tongues, but as this new book from Wensley Clarkson shows, Palmer’s misdeeds were epic and definitely world class. Meanwhile, Palmer had not been idle, at least in the sense of criminality. He had set up in the timeshare business, perpetrating what was later proved to be a massive scam. When he was eventually brought to justice, it was alleged that he had swindled 20,000 people out of a staggering £30,000,000. In 2001 he was sentenced to eight years in jail, but his ill-gotten gains were never recovered.

Meanwhile, Palmer had not been idle, at least in the sense of criminality. He had set up in the timeshare business, perpetrating what was later proved to be a massive scam. When he was eventually brought to justice, it was alleged that he had swindled 20,000 people out of a staggering £30,000,000. In 2001 he was sentenced to eight years in jail, but his ill-gotten gains were never recovered.