Frank Marshal is a seventy year-old former senior detective. He lives in a former farmhouse in Snowdonia, and volunteers as a national park ranger. He has, as they say, baggage. His wife Rachel has dementia. His son committed suicide in that self same house. His daughter Caitlin lives in England with her waster of a boyfriend and their son Sam. A not-so-near neighbour, as the area is sparsely populated, is another retired from the justice system, but Annie Taylor was a High Court Judge. Now, her sister Megan has gone missing from her rented caravan in a hilltop trailer park.

The book has a prologue which describes a woman – time-frame presumably the present – being held against her will in a remote location. When Marshal discovers bloodstains beneath the decking of Megan’s caravan, a full police investigation kicks in. Megan’s errant son, Callum, had lived with her in the caravan. Annie and Marshal track him down to his (absent) father’s house. The youth tries to escape on his moped. Marshal pursues him, but only succeeds in running him off the road into a river. Marshal rescues him, but now Callum is in hospital, suffering from amnesia. Big question. Is the memory loss genuine or a pretence?

Marshal may be a gentle father, grandfather and former policeman, but he would never survive the current scrutiny that subtly shapes modern officers to the mould set by the metropolitan liberals who run the UK legal system. Only the knowledge of the disastrous consequences of him shooting a predatory salmon poacher prevents him from pulling the trigger while, when Caitlin’s lowlife partner – TJ – arrives in Wales demanding access to his son, Marshal has no compunction in planting several bags of marching powder (recently discovered hidden in Megan’s caravan) in TJ’s car. And if the local police should find the drugs, then who is he to correct their sums when they make two plus two equal five?P.

When the body of Annie’s sister is found dead on the beach at Barmouth, strangled with thin wire, Marshal has a grim thought running through his thoughts. The wire garotte was the favoured method of a notorious serial killer, Keith Tatchell years earlier. Now Tatchell is serving life imprisonment. Two equally horrific options spring to Marshal’s mind: was Tatchell wrongly convicted and is the real killer still out there?; is Meghan’s killer someone connected to Tatchell and seeking revenge?

McCleave gives us a brilliant plot twist to reveal the true villain, but ends the novel with a suggestion that Frank Marshal may have more trouble on his hands in the next installment of what promises to be an addictive series.

I could no more be a professional writer than I could open the batting for England. The pressure to write something that sells and produces good reviews – and pays the bills – would, for me, be intolerable. Writers (unless they are TV celebrities) must constantly search for some draw, some hook, that will attract readers – and sales. I read hundreds of crime novels and, amid the gimmicks, the split time frames and the hysteria of desperate publicists, it is a relief to read a novel that is just impeccably written, with a solid narrative, and peopled by plausible characters. Marshal of Snowdonia is one such, and I can heartily recommend it. It was published by Stamford Publishing earlier this year.

Catherine Ryan Howard shines an unforgiving light on the way in which the media treats the parents and family of women or children who have been abducted or murdered. Jennifer Gold was the youngest of the three missing women. She was conventionally beautiful, a scholar, high achiever and photogenic. Likewise her mother Margaret is polished, well groomed and an assured media performer. By contrast, Tana Meehan – the first woman to be abducted – was overweight and something of a wreck of a person, having left her husband to go home to live with her elderly and ill parents. Nicki O’Sullivan, or so it was reported, had been last seen staggering around on the pavement after drinking too much at a party.

Catherine Ryan Howard shines an unforgiving light on the way in which the media treats the parents and family of women or children who have been abducted or murdered. Jennifer Gold was the youngest of the three missing women. She was conventionally beautiful, a scholar, high achiever and photogenic. Likewise her mother Margaret is polished, well groomed and an assured media performer. By contrast, Tana Meehan – the first woman to be abducted – was overweight and something of a wreck of a person, having left her husband to go home to live with her elderly and ill parents. Nicki O’Sullivan, or so it was reported, had been last seen staggering around on the pavement after drinking too much at a party.

Nikki Hardcastle

Nikki Hardcastle

Leslie Wolfe has, then, set several hares running, to use the venerable English metaphor. The rogue cop – Herb Scott – is a truly nasty piece of work, and seems to have half the Sheriff’s Department under his thumb, as when his wife, Nicole, has reported her many beatings as a crime, nothing ever happens. The mis-identification of the murdered girl is a seemingly unsolvable mystery. Were there ever two girls, or are they one and the same? Does the conundrum stem from a complex inheritance issue involving the wealthy Caldwell family? The Caldwells are magnificently disfunctional, riven with bitterness and jealousy, and to spice matters up even more, there is the deadly whiff of incest in the air.

Leslie Wolfe has, then, set several hares running, to use the venerable English metaphor. The rogue cop – Herb Scott – is a truly nasty piece of work, and seems to have half the Sheriff’s Department under his thumb, as when his wife, Nicole, has reported her many beatings as a crime, nothing ever happens. The mis-identification of the murdered girl is a seemingly unsolvable mystery. Were there ever two girls, or are they one and the same? Does the conundrum stem from a complex inheritance issue involving the wealthy Caldwell family? The Caldwells are magnificently disfunctional, riven with bitterness and jealousy, and to spice matters up even more, there is the deadly whiff of incest in the air.

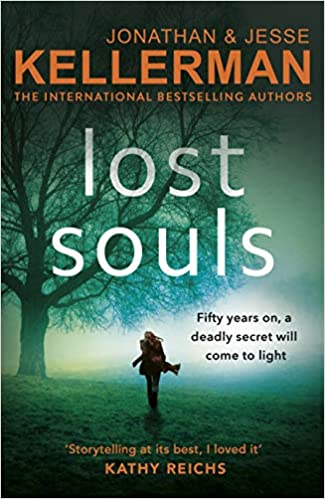

Lost Souls is something of an oddity, and no mistake. There’s nothing at all wrong with the novel itself apart from something of an identity crisis. Search for it on Amazon UK, and up it comes, but the page URL contains the title Half Moon Bay. Search for Half Moon Bay and up comes the same novel, but with a different cover. It looks as though Half Moon Bay is the Penguin Random House American title, while on this side of the Atlantic Century are going with Lost Souls.

Lost Souls is something of an oddity, and no mistake. There’s nothing at all wrong with the novel itself apart from something of an identity crisis. Search for it on Amazon UK, and up it comes, but the page URL contains the title Half Moon Bay. Search for Half Moon Bay and up comes the same novel, but with a different cover. It looks as though Half Moon Bay is the Penguin Random House American title, while on this side of the Atlantic Century are going with Lost Souls.

As Edison tries to link the skeleton of the baby with the abandoned cuddly toy, he accepts an ‘off-the-books’ job. A wealthy businessman, Peter Franchette, asks him to try to find the truth about his missing sister. Possibly abducted, perhaps murdered, she has disappeared into a complexity of disfunctional family events – deaths, walkouts, divorces, remarriages and rejections.

As Edison tries to link the skeleton of the baby with the abandoned cuddly toy, he accepts an ‘off-the-books’ job. A wealthy businessman, Peter Franchette, asks him to try to find the truth about his missing sister. Possibly abducted, perhaps murdered, she has disappeared into a complexity of disfunctional family events – deaths, walkouts, divorces, remarriages and rejections.

Nick Fennimore is a forensic psychologist, and a Professor at the University of Aberdeen. His past gives him a painful and heartfelt stake in the hunt for a serial killer, as his own wife and child were snatched. Both are now lost to him; wife Rachel, because her body was found shortly after the abduction., and daughter Suzie – well, she is just lost. Neither sight nor sound of her has been sensed in the intervening years, but Fennimore clutches at the straw of her still being alive, and he feverishly scans his own personal CCTV footage of the Paris streets and boulevards in the hope of catching a glimpse of her.

Nick Fennimore is a forensic psychologist, and a Professor at the University of Aberdeen. His past gives him a painful and heartfelt stake in the hunt for a serial killer, as his own wife and child were snatched. Both are now lost to him; wife Rachel, because her body was found shortly after the abduction., and daughter Suzie – well, she is just lost. Neither sight nor sound of her has been sensed in the intervening years, but Fennimore clutches at the straw of her still being alive, and he feverishly scans his own personal CCTV footage of the Paris streets and boulevards in the hope of catching a glimpse of her.

Jack Grimwood’s Moskva sets out to convince us that there is room for one more tale of conflicted lives in a modern Russia full of paradox and uncertainty. The book came out in hardback earlier this year, and is now available in paperback, from Penguin. Does Grimwood, who made his name writing science fiction and fantasy novels, hit the spot?

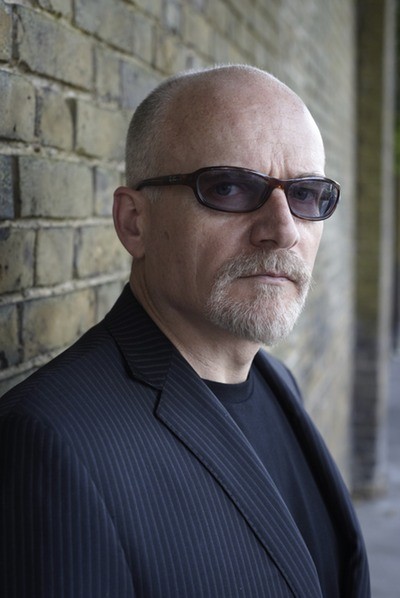

Jack Grimwood’s Moskva sets out to convince us that there is room for one more tale of conflicted lives in a modern Russia full of paradox and uncertainty. The book came out in hardback earlier this year, and is now available in paperback, from Penguin. Does Grimwood, who made his name writing science fiction and fantasy novels, hit the spot? The breadth of this novel in terms of time sometimes makes it hard to work out who has done what to whom. Patience – and a spot of back-tracking – will pay dividends, however, and the narrative provides a salutary reminder of the sheer magnitude of the numbers of Russian dead in WWII, and the resultant near-psychosis about The West. To top-and-tail this review and answer the earlier question as to whether Jack Grimwood (right) “hits the spot”, I can give a resounding “Yes!”. Yes, the plot is complex, and yes, you will need your wits about you, but yes, it’s a riveting read; yes, Tom Fox is a flawed but engaging central character, and yes, Grimwood has sharp-elbowed his way into the line-up of novelists who have written convincing crime novels set in the enigma that is Russia.

The breadth of this novel in terms of time sometimes makes it hard to work out who has done what to whom. Patience – and a spot of back-tracking – will pay dividends, however, and the narrative provides a salutary reminder of the sheer magnitude of the numbers of Russian dead in WWII, and the resultant near-psychosis about The West. To top-and-tail this review and answer the earlier question as to whether Jack Grimwood (right) “hits the spot”, I can give a resounding “Yes!”. Yes, the plot is complex, and yes, you will need your wits about you, but yes, it’s a riveting read; yes, Tom Fox is a flawed but engaging central character, and yes, Grimwood has sharp-elbowed his way into the line-up of novelists who have written convincing crime novels set in the enigma that is Russia.