Fans of John Lawton’s wonderful Fred Troy books, which began with Blackout (1995) will be delighted that the enigmatic London copper, with his intuitive skills and shameless womanising, makes an appearance here. Throughout the series Troy, son of an exiled Russian aristocrat and media baron, subsequently crosses the paths of all manner of real life characters including, memorably, Nikita Kruschev. For those interested in Troy’s back-story, this link Fred Troy may be of interest. He is not, however, central to this story. We rub shoulders with him, for sure, and also with his brother Rod, a Labour MP who serves in Clement Attlee’s postwar government. We are also reminded of characters from the previous novels – Russian soldier and spy Larissa Tosca, and the doomed Auschwitz cellist Meret Voytek. The book begins with sheer delight.

“Brompton Cemetery was full of dead toffs. Just now Troy was standing next to a live one. John Ernest Stanhope FitzClarence Ormond Brack, 11th Marquis of Fermanagh, eligible bachelor, man-about-town, and total piss artist.”

As ever in Lawton’s novels, the timeframe shifts. He takes us to 1945, the year of Hitler’s final annihilation, and to 1960 and the capture of Adolf Eichmann. Central to story is the fate of Europe’s Jews, their destruction at the hands of the Nazis, and then their almost complete rejection by Poland, Palestine, Britain, America and Russia after what was, for them, a hollow victory in 1945. Lawton’s story hinges on the lives of three young men. First is Sam Fabian, a German Jew, a mathematician and physicist who is saved from Auschwitz by a misfiring SS Luger and a compassionate Red Army officer. Then we have Jay Heller, a gifted English Jew who, immediately after joining up in 1940, is head hunted into the British intelligence services. Finally, we have Klaus LInz von Niegutt, minor member of what remains of the German aristocracy, who finds his way – or is led – into the SS. He is, however, not a violent man, and only does the bare minimum to remain ‘one of the chosen’. His significance in the novel is that he was one of the scores of staff – cooks, clerks and secretaries – who were in Hitler’s bunker in those fateful days at the end of April 1945.

With an audacious plot twist, Lawton gets Sam Fabian to England, where he finds work with a millionaire German Jew called Otto Ohnherz whose empire while not overtly criminal, is founded on the success of ventures that, while not quite illegal, are extremely profitable. He can afford to employ the best professionals. This is his barrister:

“It was said of Jago that by the time he’d finished a cross-examination, the witness would be swearing Tom, Tom, the Piper’s son had been nowhere near the pig and had in fact been eating curds and whey with Miss Muffet at the time.”

When Ohnerz dies, Jay takes over the empire, and becomes involved with maintaining Ohnerz’s rental property business. While making sure the money still rolls in, he sets out to improve the houses, particularly those rented by tenants recently arrived from the Caribbean. It is when Jay’s broken body is found on the pavement below his headquarters that the story seemingly takes a turn towards the impossible. What Troy and the pathologist discover certainly had me scratching my head for a while. Lawton’s use of separate narratives and times allows him to set a seemingly unsolvable conundrum regarding the ultimate fates of Jay, Sam and Klaus. To be fair, he provides clues, using a rather clever literary device. I won’t reveal what it is, but when you reach the last section of the book, you may need to revisit earlier pages. Smoke and Embers shows a profound understanding of the dark realpolitik that followed the end of the war in Europe, and is full of Lawton’s customary wit and wizardry. It is published by Grove Press UK and is available now.

What is happening then, in Murder Most Vile? All too often these days, I am a late arrival at the ball and this is the ninth in a series centred on a pair of investigators in 1950s England. Donald Langham is a London novelist, who runs an investigation agency with business partner Ralph Ryland. Langham’s wife, Maria Dupré, is a literary agent. Here, Langham is engaged by a rather unpleasant and misanthropic – but very rich – old man named Vernon Lombard. Lombard has a daughter and two sons, and the favourite one of the two boys, a feckless artist called Christopher, is missing.

What is happening then, in Murder Most Vile? All too often these days, I am a late arrival at the ball and this is the ninth in a series centred on a pair of investigators in 1950s England. Donald Langham is a London novelist, who runs an investigation agency with business partner Ralph Ryland. Langham’s wife, Maria Dupré, is a literary agent. Here, Langham is engaged by a rather unpleasant and misanthropic – but very rich – old man named Vernon Lombard. Lombard has a daughter and two sons, and the favourite one of the two boys, a feckless artist called Christopher, is missing.

We are in an anonymous little town in the Berry region of central France, and it is the middle years of the 1950s. Jonas Milk is a mild-mannered dealer in second hand books. His shop, his acquaintances, the c

We are in an anonymous little town in the Berry region of central France, and it is the middle years of the 1950s. Jonas Milk is a mild-mannered dealer in second hand books. His shop, his acquaintances, the c Jonas Milk has a wife. Two years earlier he had converted to Catholicism and married Eugénie Louise Joséphine Palestri – Gina – a voluptuous and highly sexed woman sixteen years his junior. No doubt the frequenters of the Vieux-Marché have their views on this marriage, but they are polite enough to keep their opinions to themselves, at least when Jonas is within earshot. But then Gina disappears, taking with her no bag or change of clothing. The one thing she does take, however, is a selection of a very valuable stamp collection that Jonas has put together over the years, not through major purchases from dealers, but through his own obsessive examination of relatively commonplace stamps, some of which turn out to have minute flaws, thus making their value to other collectors spiral to tens of thousands of francs.

Jonas Milk has a wife. Two years earlier he had converted to Catholicism and married Eugénie Louise Joséphine Palestri – Gina – a voluptuous and highly sexed woman sixteen years his junior. No doubt the frequenters of the Vieux-Marché have their views on this marriage, but they are polite enough to keep their opinions to themselves, at least when Jonas is within earshot. But then Gina disappears, taking with her no bag or change of clothing. The one thing she does take, however, is a selection of a very valuable stamp collection that Jonas has put together over the years, not through major purchases from dealers, but through his own obsessive examination of relatively commonplace stamps, some of which turn out to have minute flaws, thus making their value to other collectors spiral to tens of thousands of francs.

Cassidy is an ex-serviceman, and in Night Watch he becomes involved in an issue which is way, way above his pay-grade. The initial reaction of the USA to former Nazis in the months immediately following May 1945 was simple – Hang ‘Em High. But as the government realised that highly trained German scientists and engineers were being harvested by the new enemy – Soviet Russia – the bar was significantly lowered, with the philosophy that these men and women might be bastards, but at least they’re our bastards.

Cassidy is an ex-serviceman, and in Night Watch he becomes involved in an issue which is way, way above his pay-grade. The initial reaction of the USA to former Nazis in the months immediately following May 1945 was simple – Hang ‘Em High. But as the government realised that highly trained German scientists and engineers were being harvested by the new enemy – Soviet Russia – the bar was significantly lowered, with the philosophy that these men and women might be bastards, but at least they’re our bastards. concentration camp survivor, ostensibly just an old guy driving tourists around Central Park in his horse cab, but secretly hunting down those who imprisoned him and killed his family, is found dead with strange puncture wounds in his neck. A businessman dives through the high window of his hotel – without bothering to open it first – and no-one saw anything. Not the concierge, and especially not the dead man’s co-workers, who were in an adjacent room. Two deaths. Two cases which Cassidy’s boss wants put to bed as quickly as possible. Two lives snuffed out, and Cassidy senses a connection. A connection leading to money, national security, powerful people – and big, big trouble for a humble NYPD cop.

concentration camp survivor, ostensibly just an old guy driving tourists around Central Park in his horse cab, but secretly hunting down those who imprisoned him and killed his family, is found dead with strange puncture wounds in his neck. A businessman dives through the high window of his hotel – without bothering to open it first – and no-one saw anything. Not the concierge, and especially not the dead man’s co-workers, who were in an adjacent room. Two deaths. Two cases which Cassidy’s boss wants put to bed as quickly as possible. Two lives snuffed out, and Cassidy senses a connection. A connection leading to money, national security, powerful people – and big, big trouble for a humble NYPD cop.

here are one or two significant name drops which help boost authenticity, amongst them a guest appearance by the sinister head of the CIA, Allen Dulles. Cassidy himself doesn’t do wisecracks, but there is plenty of snappy dialogue and verbal slaps in the face to keep us awake. This, after a post mortem:

here are one or two significant name drops which help boost authenticity, amongst them a guest appearance by the sinister head of the CIA, Allen Dulles. Cassidy himself doesn’t do wisecracks, but there is plenty of snappy dialogue and verbal slaps in the face to keep us awake. This, after a post mortem:

“One of the greatest anti-heroes ever written,” says Lee Child of Bernie Gunther, the world weary, wise-cracking former German cop, and sometime acquaintance of such diverse historical characters as Reinhard Heydrich, Joseph Goebbels, Eva Peron and William Somerset Maugham. I was several chapters into this, the latest episode in Gunther’s career, when I heard the dreadful news of the death of his creator, Philip Kerr (left) at the age of 62. “No age at all,” as the saying goes.

“One of the greatest anti-heroes ever written,” says Lee Child of Bernie Gunther, the world weary, wise-cracking former German cop, and sometime acquaintance of such diverse historical characters as Reinhard Heydrich, Joseph Goebbels, Eva Peron and William Somerset Maugham. I was several chapters into this, the latest episode in Gunther’s career, when I heard the dreadful news of the death of his creator, Philip Kerr (left) at the age of 62. “No age at all,” as the saying goes.

Hitler could certainly have taken a lesson from the Old Man (Adenauer, left) It was not the men with guns who were going to rule the world but businessmen …. with their slide rules and actuarial tables, and thick books of obscure new laws in three different languages.”

Hitler could certainly have taken a lesson from the Old Man (Adenauer, left) It was not the men with guns who were going to rule the world but businessmen …. with their slide rules and actuarial tables, and thick books of obscure new laws in three different languages.”

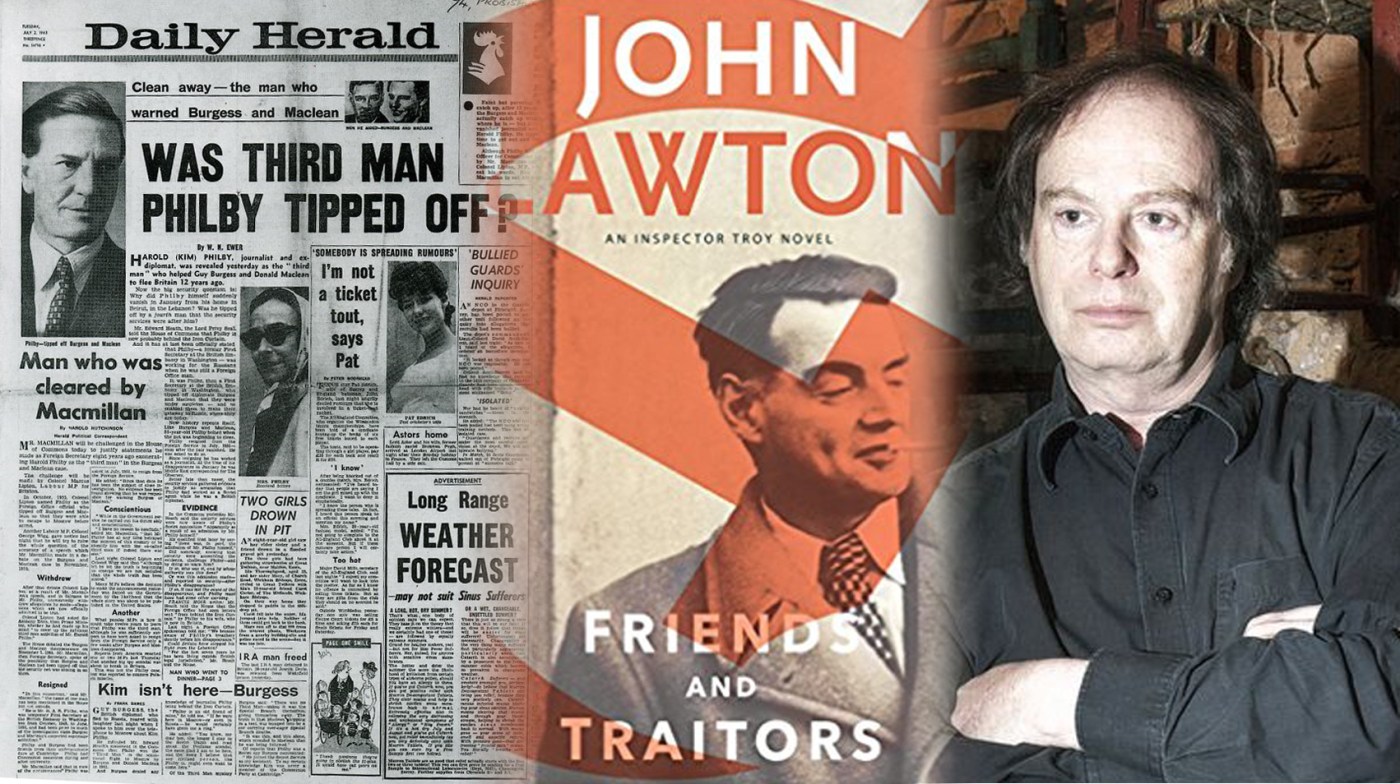

Friends and Traitors focuses mostly on the 1951 defection – and its aftermath – of intelligence officer Guy Burgess, to the Soviet Union. A huge embarrassment to the British government at the time, it was also about personalities, Britain’s place in the New World Order – and its attitudes to homosexuality. Burgess’s usefulness to the Soviets was largely symbolic, but the crux of the story is the events surrounding Burgess’s regrets, and heartfelt wish to come home. Troy interviews him in a Vienna hotel.

Friends and Traitors focuses mostly on the 1951 defection – and its aftermath – of intelligence officer Guy Burgess, to the Soviet Union. A huge embarrassment to the British government at the time, it was also about personalities, Britain’s place in the New World Order – and its attitudes to homosexuality. Burgess’s usefulness to the Soviets was largely symbolic, but the crux of the story is the events surrounding Burgess’s regrets, and heartfelt wish to come home. Troy interviews him in a Vienna hotel.

Lawton (right) was born in 1949, so would have only the vaguest memories of growing up in an austere and fragile post-war Britain, but he is a master of describing the contradictions and social stresses of the middle years of the century. Here, he describes Westcott, a notoriously persistent MI5 interrogator, sent to quiz Troy on the events in Vienna:

Lawton (right) was born in 1949, so would have only the vaguest memories of growing up in an austere and fragile post-war Britain, but he is a master of describing the contradictions and social stresses of the middle years of the century. Here, he describes Westcott, a notoriously persistent MI5 interrogator, sent to quiz Troy on the events in Vienna:

Murder In Mt Martha is one such book. For those who have never visited Melbourne, Mount Martha is a town on the Mornington Peninsula, best known as what we Brits would call a seaside town. The ‘Mount’ is a shade over 500 ft, and is named after the wife of one of the early settlers. Author Janice Simpson (left) has taken a real-life unsolved murder from the 1950s as one thread, and created another involving a present day post-grad student who is interviewing an old man about his early life in the post-war Victorian city. Simpson has woven the two threads together to create a fabric that shimmers, shocks and surprises.

Murder In Mt Martha is one such book. For those who have never visited Melbourne, Mount Martha is a town on the Mornington Peninsula, best known as what we Brits would call a seaside town. The ‘Mount’ is a shade over 500 ft, and is named after the wife of one of the early settlers. Author Janice Simpson (left) has taken a real-life unsolved murder from the 1950s as one thread, and created another involving a present day post-grad student who is interviewing an old man about his early life in the post-war Victorian city. Simpson has woven the two threads together to create a fabric that shimmers, shocks and surprises. Simpson keeps Szabo blissfully unaware that Arthur Boyle is a relative of Ern Kavanagh. Arthur only recalls him in fits and starts, believing that he was his uncle, but Simpson lets us into the secret as she describes Ern’s life over half a century earlier. The book opens with a graphic description of the brutal murder of an innocent teenager whose parents have reluctantly allowed her to travel alone to her first party. There is never any doubt in our minds that Ern Kavanagh killed the girl, but we are kept on a knife-edge of not knowing if he will get away with the murder.

Simpson keeps Szabo blissfully unaware that Arthur Boyle is a relative of Ern Kavanagh. Arthur only recalls him in fits and starts, believing that he was his uncle, but Simpson lets us into the secret as she describes Ern’s life over half a century earlier. The book opens with a graphic description of the brutal murder of an innocent teenager whose parents have reluctantly allowed her to travel alone to her first party. There is never any doubt in our minds that Ern Kavanagh killed the girl, but we are kept on a knife-edge of not knowing if he will get away with the murder.