Inevitably, Marwood’s profession brought him face to face with some of the most notorious criminals of the second half of the 19th century. One of these was Charles Peace. Seldom can a man’s surname have been so inappropriate. Peace,after killing a policeman in Manchester, fled to his native Sheffield, where he became obsessed with his neighbour’s wife, eventually shooting her husband dead. Settling in London, he carried out multiple burglaries before being caught in the prosperous suburb of Blackheath, wounding the policeman who arrested him. He was linked to the Sheffield murder, and tried at Leeds Assizes. Found guilty, he was hanged by Marwood at Armley Prison on 25th February 1879.

One of Marwood’s jobs involved the despatch of someone who was, quite literally, ‘close to home’. In August 1875 he presided over the execution of a young man from Louth, Peter Blanchard, who had savagely murdered his girlfriend in a fit of jealous madness. I have written about the case elsewhere on this website, and if you click this link, it will take you to the feature. Blanchard’s death was described in the Lincolnshire Chronicle.

Perhaps the most controversial period of Marwood’s career as hangman was as a result of rising tensions in Ireland in the 1880s. The Irish nationalists, in particular the group known as The Irish National Invincibles, were determined to inflict damage on what they saw as British imperialism, and on 6th May 1882, two high profile British officials, Thomas H Burke and Lord Frederick Cavendish were murdered while walking in Dublin’s Phoenix Park. In Kilmainham Jail, Dublin, on 14th May 1883, Marwood hanged the five men found guilty of the murder. In the previous year, 15th December, Marwood had hanged Maolra Seoighe for his part in the murder of a local family in Maamtrasna in County Mayo. The five ‘invincibles’ are pictured below:

Such was the animosity between the Irish republicans and anyone thought to be an agent of the British state that when Marwood died – officially of pneumonia and jaundice – in September 1883, there was speculation that he had been assassinated by the Fenians. This was from the Leeds Times:

The Irish lnvincibles sent him a threatening missive, warning him that if he set foot upon Irish soil he would not depart alive. Marwood was carefully protected while in Ireland and the threats against his life prove to be inoperative. Rumours having gained currency that the Irish Invincibles were in someway responsible for the illness and death of .Marwood, it was deemed advisable to inform the coroner. Arrangements were-made for the interment of the body, but pending the coroner’s decision the funeral was delayed. The inquest was held on Thursday. The coroner remarked that deceased’s death was not unexpected. Two medical men attended him. Sarah Moody, who had nursed deceased, was not aware that anything of an unfair kind was administered to him. Mrs. Marwood, wife of deceased, said her husband went to Lincoln on Friday week. He had not been well since. She asked him on Sunday if anything of an injurious kind was given to him. He said “no” and made light of the matter. She did not believe he had received any threatening letters since one published a year ago. He had no fear or expectation of violence at the hands of the Irish. Dr. Hadden and Mr. Jelland, surgeon, who had attended deceased, said that their patient died from natural causes, and a verdict to that effect was returned. The remains of Marwood were afterwards interred in Trinity Churchyard.

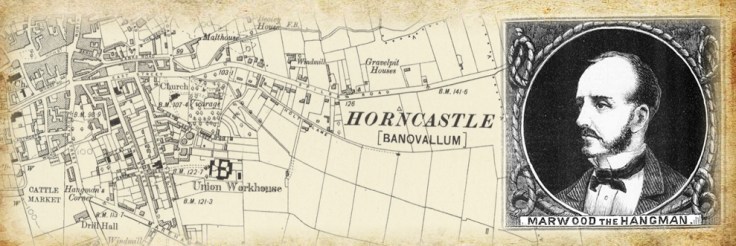

A sad postscript to the life of William Marwood was that, despite his quite prodigious earnings from his job, he had mismanaged his affairs. Some years after his death, this was the report in The Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser:

“During my stay in Horncastle I got to know that Marwood had been doing duty as a hangman some time before his neighbours knew of the circumstance. And it would have been a secret for some time longer, but that a Horncastle man happened to be present at an execution which took place at some distant town, and, on seeing the operator, recognised his fellow-townsman. The news spread like wildfire at Horncastle, and when Marwood arrived home he found himself the object of a few attentions which were more demonstrative than nice. And for some time after, when he started for, or came back from, an execution, he was followed about by people who showed no displeasure by hooting him, and by beating tin kettles, pots, and pans. This grew to be a veritable nuisance, so bad that Marwood was compelled to write to the Home Secretary claiming protection. After he had done this the head of Horncastle police was communicated with, and since that time Marwood has been permitted to depart from, and return to this town without molestation; in fact, he walks about the place without attracting any special attention. I noticed that his fellow townsmen greeted him in an unmarked but friendly manner, and he appeared to be on good terms with everybody. He keeps a shoemaker’s shop, and is comfortably off, owning several houses in Horncastle.”

“During my stay in Horncastle I got to know that Marwood had been doing duty as a hangman some time before his neighbours knew of the circumstance. And it would have been a secret for some time longer, but that a Horncastle man happened to be present at an execution which took place at some distant town, and, on seeing the operator, recognised his fellow-townsman. The news spread like wildfire at Horncastle, and when Marwood arrived home he found himself the object of a few attentions which were more demonstrative than nice. And for some time after, when he started for, or came back from, an execution, he was followed about by people who showed no displeasure by hooting him, and by beating tin kettles, pots, and pans. This grew to be a veritable nuisance, so bad that Marwood was compelled to write to the Home Secretary claiming protection. After he had done this the head of Horncastle police was communicated with, and since that time Marwood has been permitted to depart from, and return to this town without molestation; in fact, he walks about the place without attracting any special attention. I noticed that his fellow townsmen greeted him in an unmarked but friendly manner, and he appeared to be on good terms with everybody. He keeps a shoemaker’s shop, and is comfortably off, owning several houses in Horncastle.”

This is a new police procedural from Stuart MacBride (left) and it introduces Detective Sergeant Lucy McVeigh. Her beat is the fictional town of Oldcastle (not to be confused with the actual city of Oldcastle, which lies between Aberdeen and Dundee). Aberdeen, of course, is where DS Logan McRae operated in the hugely successful earlier series from MacBride. Also, DS McVeigh comes across – to me at any rate – as a younger version of McRae’s boss, the foul-mouthed and acerbic DCI Roberta Steel. McVeigh is equally sharp tempered, and similarly indisposed to suffer fools gladly.

This is a new police procedural from Stuart MacBride (left) and it introduces Detective Sergeant Lucy McVeigh. Her beat is the fictional town of Oldcastle (not to be confused with the actual city of Oldcastle, which lies between Aberdeen and Dundee). Aberdeen, of course, is where DS Logan McRae operated in the hugely successful earlier series from MacBride. Also, DS McVeigh comes across – to me at any rate – as a younger version of McRae’s boss, the foul-mouthed and acerbic DCI Roberta Steel. McVeigh is equally sharp tempered, and similarly indisposed to suffer fools gladly. As the search for The Bloodsmith continues, and Lucy McVeigh struggles to keep abreast of that investigation, as well as her battle with the Black family and coping with the mental agonies of Benedict Strachan, MacBride treats us to his signature mixture of Noir, visceral horror and bleak humour. Even though his Oldcastle is a fictional place, it is vividly brought to life to the extent that I would not be in the least surprised if the author has a map of the place hanging on the wall of his writing room. The situation becomes ever more complex for Lucy McVeigh when she learns there is a connection between the murdered former policeman and Benedict Strachan. That connection is a prestigious and exclusive independent school, known colloquially as St Nicks’s. When she visits the school, she unearths more questions than answers.

As the search for The Bloodsmith continues, and Lucy McVeigh struggles to keep abreast of that investigation, as well as her battle with the Black family and coping with the mental agonies of Benedict Strachan, MacBride treats us to his signature mixture of Noir, visceral horror and bleak humour. Even though his Oldcastle is a fictional place, it is vividly brought to life to the extent that I would not be in the least surprised if the author has a map of the place hanging on the wall of his writing room. The situation becomes ever more complex for Lucy McVeigh when she learns there is a connection between the murdered former policeman and Benedict Strachan. That connection is a prestigious and exclusive independent school, known colloquially as St Nicks’s. When she visits the school, she unearths more questions than answers.

Last Seen Alive is the third book by Jane Bettany (left) featuring the Derbyshire copper DI Isabel Blood. The story begins when Anna Matheson, a single mother who works at a large confectionery firm, fails to pick up her infant son from the child minder after a social event at work. Lauren Talbot, the child minder, raises the alarm late at night, but precious hours elapse before morning comes and the police are able to start making enquiries.

Last Seen Alive is the third book by Jane Bettany (left) featuring the Derbyshire copper DI Isabel Blood. The story begins when Anna Matheson, a single mother who works at a large confectionery firm, fails to pick up her infant son from the child minder after a social event at work. Lauren Talbot, the child minder, raises the alarm late at night, but precious hours elapse before morning comes and the police are able to start making enquiries.

The Tucumcari Press is based in Tucson, Arizona, and they have kindly sent me a couple of books by Kirk Alex. So who is he? He can tell us:

The Tucumcari Press is based in Tucson, Arizona, and they have kindly sent me a couple of books by Kirk Alex. So who is he? He can tell us: In L.A., unless you have the flashy car, luxury apartment, good paying job, you can forget about having a woman in your life to be with, any of that; so yeah, we hung in there alone. What doesn’t break you makes you stronger, so they say.

In L.A., unless you have the flashy car, luxury apartment, good paying job, you can forget about having a woman in your life to be with, any of that; so yeah, we hung in there alone. What doesn’t break you makes you stronger, so they say.

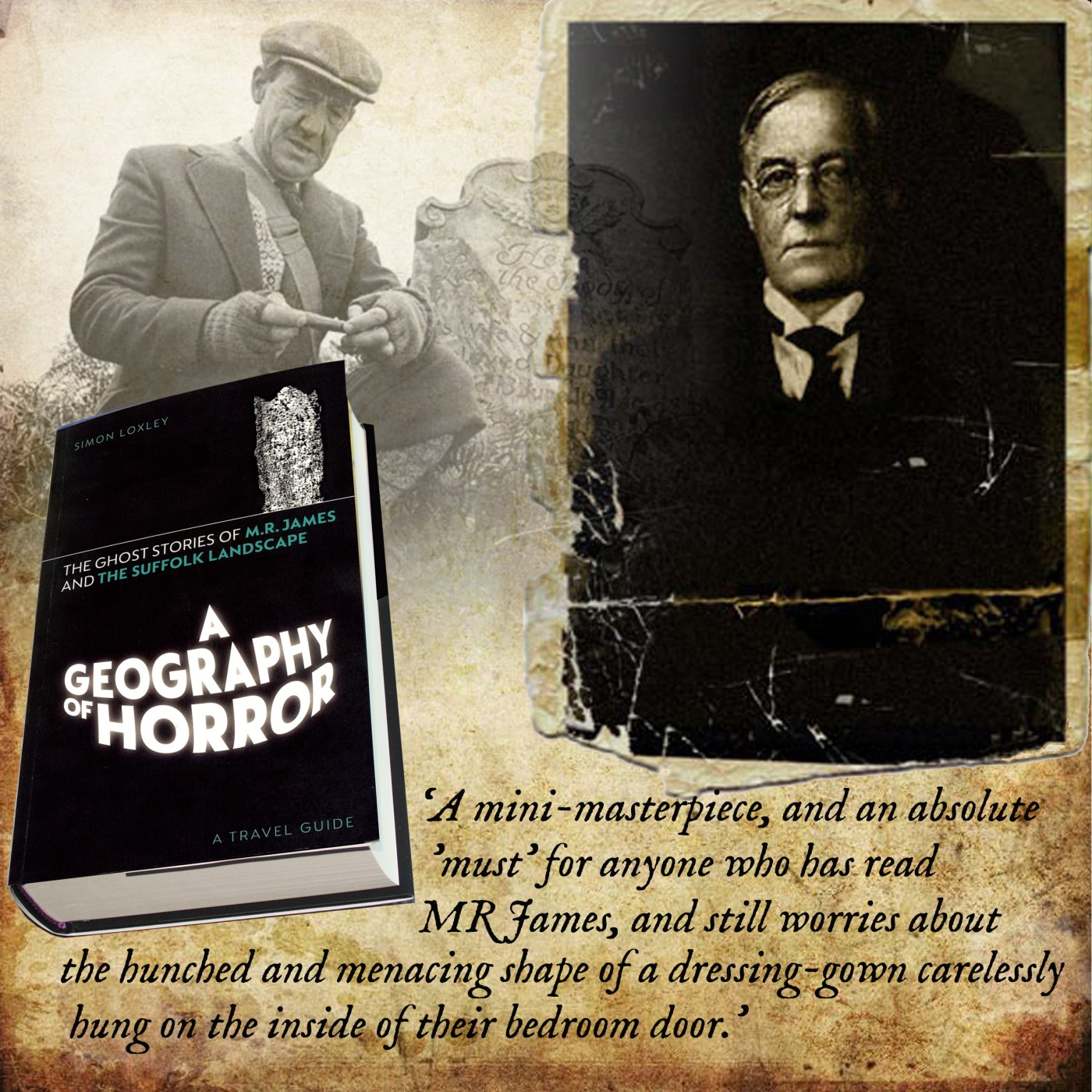

Who was the most celebrated writer of ghost stories? The genre doesn’t lend itself particularly well to longer book form, and even classics like Henry James’s The Turn of The Screw and Susan Hill’s The Woman In Black are relatively slim volumes. The master of the shorter version and, in my view, a man who unrivalled in the art of chilling the spine, was MR James. Montague Rhodes James was born in Kent in 1862, and in his main professional life he became a renowned scholar, medievalist and academic, serving as Provost of King’s College Cambridge, and Provost of Eton. His first collection of ghost stories, Ghost Stories of an Antiquary, was published in 1904 and has, as far as I am aware, never been out of print.

Who was the most celebrated writer of ghost stories? The genre doesn’t lend itself particularly well to longer book form, and even classics like Henry James’s The Turn of The Screw and Susan Hill’s The Woman In Black are relatively slim volumes. The master of the shorter version and, in my view, a man who unrivalled in the art of chilling the spine, was MR James. Montague Rhodes James was born in Kent in 1862, and in his main professional life he became a renowned scholar, medievalist and academic, serving as Provost of King’s College Cambridge, and Provost of Eton. His first collection of ghost stories, Ghost Stories of an Antiquary, was published in 1904 and has, as far as I am aware, never been out of print.