After David Mark starts his latest novel with a nod to the celebrated first three words of Herman Melville’s masterpiece, the first chapter of The Burning Time made me wonder if I had slipped off the page and fallen into a visceral nightmare straight out of the Derek Raymond playbook displayed in I Was Dora Suarez – there was blood, pain, death, distortion, madness, fire – and human disintegration.

Chapter two reminds readers that we are accompanying Inspector Aector McAvoy on his latest murder investigation. Bear-like McAvoy – based in Hull – and his beguiling gypsy wife Roisin, have been invited to an all-expenses-paid stay at a luxury hotel in Northumbria to celebrate the seventieth birthday of McAvoy’s mother. Mater and filius have become somewhat estranged over the years, mainly due to mum dispensing with Aector’s dad when her son was young, and opting for a newer, richer husband – who insisted on Aector being sent away to boarding school, causing mental scars which have not healed over the years. Aector, via this arrangement, has a step brother called Felix, older than he, and a person who subjected his younger step sibling to all kinds of mental and physical bullying back in the day. It is Felix who has organised the family gathering.

Part of the carnage in chapter one involves Ishmael Piper – a middle-aged hippy living with a twin curse, the first part being that he was the son of the late and legendary rock guitarist Moose Piper, and the second being that he is suffering from Huntington’s Chorea, the degenerative disease whose most famous victim was the American musician Woody Guthrie. Ishmael inherited much of his father’s wealth, guitars and memorabilia, but his life has become a protracted car crash. His life comes to an end when his remote cottage on the Northumberland moors is gutted by fire. He is found dead outside, his daughter Delilah clutching his hand, while one of his female companions, asleep in an upstairs room, is the second fatality. Delilah has been badly burned. Later, McAvoy sees her:

‘He wants to look away; to jerk back – to not have to see what the flame has done on half of her face. He thinks of wormholes at low tide. He can’t help himself: his imagination floods with memories; so many twisted worm-casts in the soft grainy sand.’

McAvoy is an intriguing creation. He is physically massive, but suffers from debilitating shyness and a chronic lack of social confidence. He is, however, formidably intelligent and a very, very good policeman. Crime fiction buffs will know that there is a certain trope in police novels, where the newly promoted detective becomes frustrated with paper work, and longs to be out on the street catching villains. McAvoy is more nuanced:

‘It always surprises his colleagues to realise that, in a perfect world, McAvoy would never leave the safety of his little office cubicle at Clough Road Police Station.’

The Puccini aria from Tosca, Recondita Armonia, can be translated as ‘strange harmony’, and no harmony is stranger than that between McAvoy and his wife Roisin. They share a fierce intelligence, but David Mark portrays her as slender, captivatingly beautiful and blessed – or cursed – with an intuition and silver tongue inherited from her Irish gypsy ancestors, and a dramatic contrast to her physically imposing but socially gauche husband.

McAvoy realises that he has been invited to the family gathering, not out of any desire for reconciliation, but because Felix wants him to find out the truth behind Ishmael’s death, a task at which the local police have failed. McAvoy, of course – after bouts of epic violence involving various bit-players in the drama – does find the killer, but in doing so illustrates that the birthday party was nothing other than a bitter charade. The Burning Time – a powerful and sometimes disturbing read – is published by Severn House and is available now. For more reviews of David Mark novels, click the image below.

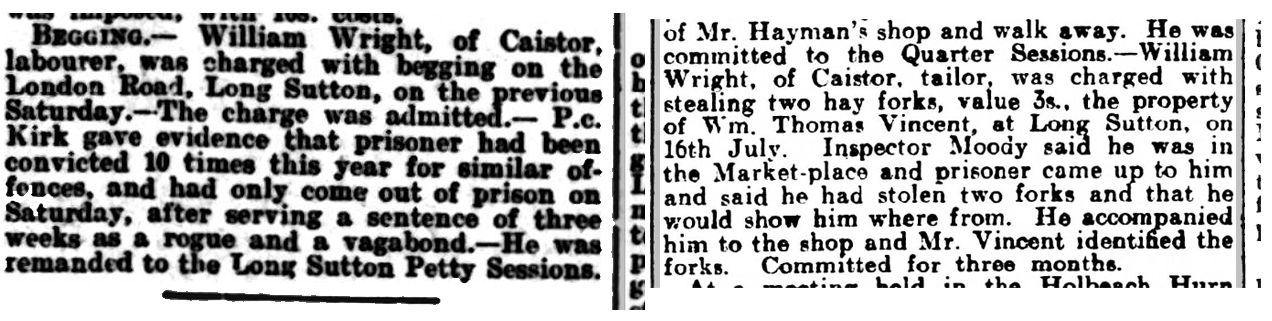

Watson (pictured) spent years working for provincial newspapers, writing up endless articles on civic functions, what passed for ‘society’ weddings, bickering councillors, glimpses of local scandals, and petty offenders appearing before bibulous local magistrates. This gave him a unique insight into what made small-town England tick. He could be acerbic, but never vicious. he usually found space to write about fictional versions of himself – local journalists. In this case, a Mr Kebble, editor of the local rag.

Watson (pictured) spent years working for provincial newspapers, writing up endless articles on civic functions, what passed for ‘society’ weddings, bickering councillors, glimpses of local scandals, and petty offenders appearing before bibulous local magistrates. This gave him a unique insight into what made small-town England tick. He could be acerbic, but never vicious. he usually found space to write about fictional versions of himself – local journalists. In this case, a Mr Kebble, editor of the local rag. In a strange way, the plot of Blue Murder is neither here nor there, as it is merely a vehicle for Watson’s beguiling way with words. It features – as do all the Flaxborough novels – the imperturbable Inspector Walter Purbright, a man benign in appearance and manner, but possessed of a sharp intelligence and an ability to spot deception and dissembling at a hundred yards distance. Long story short, a red-top national newspaper, The Herald, has been tipped off that the redoubtable burghers of Flaxborough are implicated in a blue movie, what used to be known as a stag film. On arriving in Flaxborough, the investigating team, headed by muck-raker in chief Clive Grail, assisted by his delightful PA, Miss Birdie Clemenceaux. manage to fall foul of the combative town Mayor, Charlie Hocksley. Hocksley has his finger in more local pies than the town baker can turn out, for example:

In a strange way, the plot of Blue Murder is neither here nor there, as it is merely a vehicle for Watson’s beguiling way with words. It features – as do all the Flaxborough novels – the imperturbable Inspector Walter Purbright, a man benign in appearance and manner, but possessed of a sharp intelligence and an ability to spot deception and dissembling at a hundred yards distance. Long story short, a red-top national newspaper, The Herald, has been tipped off that the redoubtable burghers of Flaxborough are implicated in a blue movie, what used to be known as a stag film. On arriving in Flaxborough, the investigating team, headed by muck-raker in chief Clive Grail, assisted by his delightful PA, Miss Birdie Clemenceaux. manage to fall foul of the combative town Mayor, Charlie Hocksley. Hocksley has his finger in more local pies than the town baker can turn out, for example:

In 2021 I reviewed an earlier contribution to the Sherlockian canon by Bonnie MacBird (left) –

In 2021 I reviewed an earlier contribution to the Sherlockian canon by Bonnie MacBird (left) –

The novel is subtitled The Memoirs of Inspector Frank Grasby, and Denzil Meyrick (left) employs the reliable plot-opener of someone in our time inheriting a wooden crate containing the papers of a long-dead police officer, and exploring what was committed to paper. Will crime writers in a hundred years hence have their characters discovering a forgotten folder in the corner of someone’s hard drive? I doubt it – it won’t be anywhere near as much fun.

The novel is subtitled The Memoirs of Inspector Frank Grasby, and Denzil Meyrick (left) employs the reliable plot-opener of someone in our time inheriting a wooden crate containing the papers of a long-dead police officer, and exploring what was committed to paper. Will crime writers in a hundred years hence have their characters discovering a forgotten folder in the corner of someone’s hard drive? I doubt it – it won’t be anywhere near as much fun.

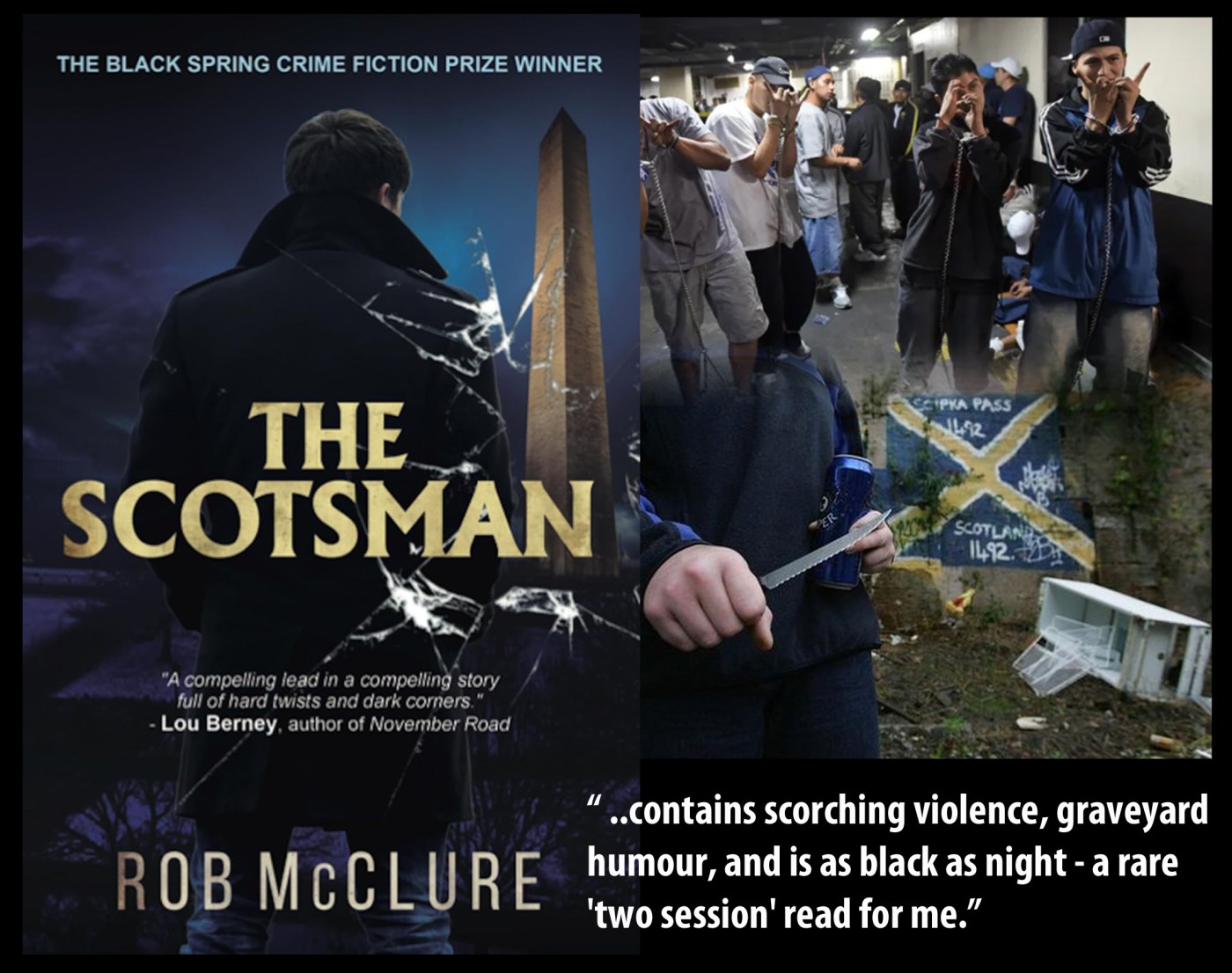

The trope of a police officer investigating a crime “off patch” or in an unfamiliar mileu is not new, especially in film. At its corniest, we had John Wayne in Brannigan (1975) as the Chicago cop sent to London to help extradite a criminal, and in Coogan’s Bluff (1968), Clint Eastwood’s Arizona policeman, complete with Stetson, is sent to New York on another extradition mission. Black Rain (1989) has Michael Douglas locking horns with the Yakuza in Japan, and who can forget Liam Neeson’s unkindness towards Parisian Albanians in Taken (2018), but apart from 9 Dragons (2009), where Michael Connolly’s Harry Bosch goes to war with the Triads in Hong Kong, I can’t recall many crime novels in the same vein. Rob McClure (left) balances this out with his debut novel, The Scotsman, which was edited by Luca Veste.

The trope of a police officer investigating a crime “off patch” or in an unfamiliar mileu is not new, especially in film. At its corniest, we had John Wayne in Brannigan (1975) as the Chicago cop sent to London to help extradite a criminal, and in Coogan’s Bluff (1968), Clint Eastwood’s Arizona policeman, complete with Stetson, is sent to New York on another extradition mission. Black Rain (1989) has Michael Douglas locking horns with the Yakuza in Japan, and who can forget Liam Neeson’s unkindness towards Parisian Albanians in Taken (2018), but apart from 9 Dragons (2009), where Michael Connolly’s Harry Bosch goes to war with the Triads in Hong Kong, I can’t recall many crime novels in the same vein. Rob McClure (left) balances this out with his debut novel, The Scotsman, which was edited by Luca Veste.