While waiting for his new quick thriller to be unleashed upon an unsuspecting world, author Frank Westworth considers creative ways to kill people…

Killer thrillers demand thrilling killers, no? I mean … that’s the whole point of them, surely. It is entirely unclear why so many folk are fascinated by creative ways of dying, but we are. Some of us are intrigued enough to write about it, maybe to see how it works, how a murder fits together, how it might feel were the author the killer. Which, usually, is not the case. Usually.

Most deaths – even the deliberate and premeditated deaths which define an actual murder – are pretty mundane. Most professional killers do it in the usual ways: either long range, the most popular and involving missiles, bombs, artillery and the like; medium range, using guys with guns operable by just the guys with the guns, and only occasionally by professionals involved in one-on-one – actual hand-to-hand combat. The latter is pretty rare, research reveals.

Research? Yes indeed. It’s not difficult to find a retired (let us pray) killer and ask. I did this, and I assume that other authors of killer thrillers do the same. Look around you; it’s statistically pretty likely that you know ex-military types. Maybe well enough to ask them all about the mechanisms. And maybe not.

Creative ways of killing apparently make a book more appealing – they certainly make writing the book more entertaining. I’ve recently completed a short story which required a surprise person being killed in a surprising way. In a disguised way; a murder disguised as an accident. And as all parties involved were military or police professionals, that was a fun challenge. Grab a copy of ‘Fifth Columnist’ if you’re interested in the resolution.

Unlike most killings, novels are written to entertain, so maybe the killing ways should also be entertaining. This is plainly a decently bizarre notion, not least because most killings are accidental, for passion or for money – think about it for a second – but I doubt that many killers do it to entertain others. Although…

So I try to provide variety, and even a little originality – entirely to entertain The Reader. So far, in three novels and a half-dozen short stories, methods of murder have included the usual handguns, sniper rifles, a rocket or two, several knives (usually long, sharp and with black blades – I took advice on that) and a couple of one-on-one slug it out fights, although the best advice with the latter is always to strike first, strike extremely hard and carry on doing that until your own life is safe. Talk to a serving soldier, preferably an infantryman.

However, I’ve also managed a couple of deaths by bathroom furniture, in the shower – dangerous places, hard surfaces, slippery and easy to clean. And for a little variety in one incident the bad guy used a catapult, while in another a nun used an exploding guitar case. It all made sense at the time. The killing I was most amused by – if it’s OK for an author to be amused by their own copy – was death by industrial strength Viagra. It was appropriate for the situation, trust me. Also titillating? OK. Maybe a little. A not so petite mort, maybe.

It’s not all violence for its own sake, though. When I working up the characters of the – ah – characters, I wanted to portray a couple of them as decent humans, not stone killers, psychopaths or the deviant fruitcakes so popular in the movies and on the telly. OK, so they’re killers – that is what soldiers do – but they do not revel in that. Let’s take the idea a little further – can you imagine a situation in which death would be a mercy? Of course you can … probably. There’s a great movie called ‘They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?’ which isn’t about contract killers in any sense (but is well worth watching all the same) which suggests the desperation which could lead someone – a very best friend, maybe – to do a deed which is entirely socially unacceptable, but which is actually a kindness, a mercy killing. I’ve told that very tale twice, using different reasons and entirely different characters. It’s not easy to write. Not at all. The exact opposite of the alleged ‘spree’ killers so beloved of so many.

An unexpected outcome of the killer novelist’s life is the popularity of the anti-hero. Not the villain, everyone has their favourite villains, from Moriarty to Hannibal Lecter, no; the anti-hero. The character whose view of life can become so bleak that he (or indeed she…) finds it increasingly easy to consider that final kill, that kill of the killer – suicide. One or more of my own characters face this, stare it down, consider it anew, find the idea appealing, so appealing that they need to distract themselves from their own final solution. Distractions? How would an increasingly nervous, distressed and unbalanced person distract themselves? It’s not easy, is it? And it’s very easy for a killer to kill themself, no matter the means or the method. And surviving a professional killer’s suicide would surely be the greatest comeback in killer history, no?

I can’t wait to write it…

FIFTH COLUMNIST comes out on 14 September 2016. This quick thriller features covert operative JJ Stoner, who uses sharp blades and blunt instruments to discreetly solve problems for the British government. A bent copper is compromising national security and needs to be swiftly neutralised, but none of the evidence will stand up in court. That’s exactly why men like Stoner operate in the shadows, ready to terminate the target once an identity is confirmed…

FIFTH COLUMNIST comes out on 14 September 2016. This quick thriller features covert operative JJ Stoner, who uses sharp blades and blunt instruments to discreetly solve problems for the British government. A bent copper is compromising national security and needs to be swiftly neutralised, but none of the evidence will stand up in court. That’s exactly why men like Stoner operate in the shadows, ready to terminate the target once an identity is confirmed…

FIFTH COLUMNIST offers an hour’s intrigue and entertainment. It features characters from the JJ Stoner / Killing Sisters series. You don’t need to have read any of the other stories in the series: you can start right here if you like. As well as a complete, stand-alone short story, Fifth Columnist includes an excerpt from The Redemption Of Charm (to be published in March 2017).

Please note that FIFTH COLUMNIST is intended for an adult audience and contains explicit scenes of a sexual and/or violent nature.

GRAB FRANK WESTWORTH’S NEW THRILLER for just 99p/99c

Amazon UK: www.amazon.co.uk/dp/B01L5TEUEG/

Amazon US: www.amazon.com/dp/B01L5TEUEG/

Shelve it on Goodreads: www.goodreads.com/book/show/31699504-fifth-columnist

READER FEEDBACK:

‘A fast-paced, high-powered thriller… Terse and stiletto streamlined and sharp as the blade of a knife.’

‘Imagine an intimate encounter between Jack Reacher and the girl with the dragon tattoo: that’s JJ Stoner and the Killing Sisters.’

‘Gritty story-telling at its best, with graphic (but well-written) sex and a plot that fires from the hip.’

‘I implore lovers of crime/thrillers to get their hands on the JJ Stoner series. Both the short and full length books are just fantastic.’

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Frank Westworth shares several characteristics with his literary anti-hero, JJ Stoner: they both play mean blues guitar and ride Harley-Davidson motorcycles. Unlike Stoner, Frank hasn’t deliberately killed anyone. Frank lives in Cornwall in the UK, with his guitars, motorcycles, partner and cat.

AUTHOR LINKS:

Facebook: www.facebook.com/killingsisters

Website: www.murdermayhemandmore.net

Blog: https://murdermayhemandmore.wordpress.com/category/frankswrite/

Amazon: www.amazon.co.uk/Frank-Westworth/e/B001K89ITA/

Goodreads: www.goodreads.com/author/show/576653.Frank_Westworth

FIFTH COLUMNIST comes out on 14 September 2016. This quick thriller features covert operative JJ Stoner, who uses sharp blades and blunt instruments to discreetly solve problems for the British government. A bent copper is compromising national security and needs to be swiftly neutralised, but none of the evidence will stand up in court. That’s exactly why men like Stoner operate in the shadows, ready to terminate the target once an identity is confirmed…

FIFTH COLUMNIST comes out on 14 September 2016. This quick thriller features covert operative JJ Stoner, who uses sharp blades and blunt instruments to discreetly solve problems for the British government. A bent copper is compromising national security and needs to be swiftly neutralised, but none of the evidence will stand up in court. That’s exactly why men like Stoner operate in the shadows, ready to terminate the target once an identity is confirmed…

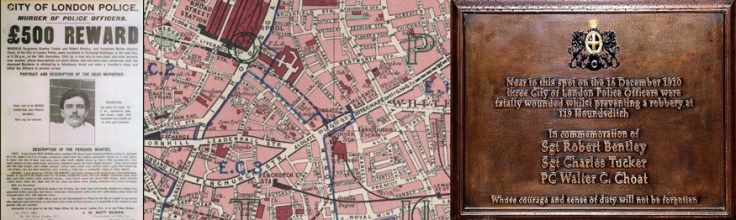

What followed was chaotic. The police, unwittingly, were walking into a situation where they would be faced with desperate men armed with sophisticated semi-automatic weapons. In the semi-darkness of the shop, there was a murderous burst of gunfire which woke people living in adjacent properties, and brought them from their beds. Three policemen were shot and killed – Sergeant Bentley, Sergeant Tucker and Constable Choat, of the City of London police. Bentley died from wounds to the shoulder and neck; Choat from six bullet wounds; Tucker from gunshots to the heart and stomach. Almost incidentally, George Gardstein was also shot – probably by one of his co-conspirators – and dragged from the scene. He died later at 59 Grove Street (now Goldring Street), off Commercial Road, a house leased to Peter Piatkov, later known as Peter The Painter.

What followed was chaotic. The police, unwittingly, were walking into a situation where they would be faced with desperate men armed with sophisticated semi-automatic weapons. In the semi-darkness of the shop, there was a murderous burst of gunfire which woke people living in adjacent properties, and brought them from their beds. Three policemen were shot and killed – Sergeant Bentley, Sergeant Tucker and Constable Choat, of the City of London police. Bentley died from wounds to the shoulder and neck; Choat from six bullet wounds; Tucker from gunshots to the heart and stomach. Almost incidentally, George Gardstein was also shot – probably by one of his co-conspirators – and dragged from the scene. He died later at 59 Grove Street (now Goldring Street), off Commercial Road, a house leased to Peter Piatkov, later known as Peter The Painter. While London came to a standstill for the memorial service for the three dead policeman at St Paul’s Cathedral of 23rd December, the colleagues of the three men had not been idle. Tracing the culprits was made no easier by the fact that many of them had a different alias for every day of the week and, in the eyes of the expatriate Russian and Latvian community in the East End, the British Police were no different from the dreaded Okhrana secret police operating in their homelands. Eventually four members of the gang were brought to court in May 1911. Peters, Duboff, Rosen and Vassileva were charged with a variety of offences including murder and conspiracy to commit burglary.

While London came to a standstill for the memorial service for the three dead policeman at St Paul’s Cathedral of 23rd December, the colleagues of the three men had not been idle. Tracing the culprits was made no easier by the fact that many of them had a different alias for every day of the week and, in the eyes of the expatriate Russian and Latvian community in the East End, the British Police were no different from the dreaded Okhrana secret police operating in their homelands. Eventually four members of the gang were brought to court in May 1911. Peters, Duboff, Rosen and Vassileva were charged with a variety of offences including murder and conspiracy to commit burglary. On 3rd January 1911, however, an event had occurred which gripped the imagination of the public at the time, and still casts a lurid shadow over a century later. Two of the gang, Svaars and Sokoloff, were believed to be holed up in a dwelling on Sidney Street in Whitechapel. The attempt to capture them featured a detachment of the Scots Guards, the fire brigade – and the Home Secretary, a certain Winston Churchill. Svaars and Sokoloff perished in the ensuing gun battle and fire, but a full account of the happenings of that day – both tragic and farcical – is for another time.

On 3rd January 1911, however, an event had occurred which gripped the imagination of the public at the time, and still casts a lurid shadow over a century later. Two of the gang, Svaars and Sokoloff, were believed to be holed up in a dwelling on Sidney Street in Whitechapel. The attempt to capture them featured a detachment of the Scots Guards, the fire brigade – and the Home Secretary, a certain Winston Churchill. Svaars and Sokoloff perished in the ensuing gun battle and fire, but a full account of the happenings of that day – both tragic and farcical – is for another time. By Peter Bartram

By Peter Bartram “Harry Roberts is our friend, is our friend, is our friend.

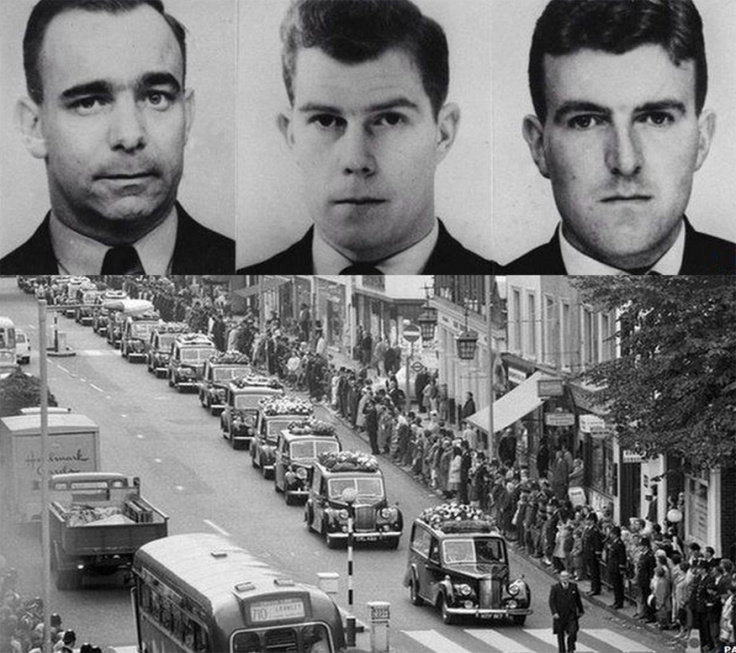

“Harry Roberts is our friend, is our friend, is our friend.  aged 30, and 25-year-old Temporary Detective Constable David Wombwell were both members of the CID based at Shepherd’s Bush police station. Their driver was Police Constable Geoffrey Roger Fox, aged 41. As the unmarked police car pulled up nearby, DS Head and DC Wombwell got out and walked over to check the van. They noticed that it had no tax disc. While the officers were checking Jack Whitney’s documents, Roberts panicked, and shot DC Wombell with a Luger pistol. When DS Head ran back towards the police car, Roberts shot him, too. Duddy sprang from the back of the van, brandishing an old Webley revolver, and joined Roberts by the police car where, together, they shot dead PC Fox. The two killers ran back and got into the van, which Whitney drove away at high speed. (Below) The murdered officers PC Fox, DC Wombwell and DS Head, and their funeral cortege.

aged 30, and 25-year-old Temporary Detective Constable David Wombwell were both members of the CID based at Shepherd’s Bush police station. Their driver was Police Constable Geoffrey Roger Fox, aged 41. As the unmarked police car pulled up nearby, DS Head and DC Wombwell got out and walked over to check the van. They noticed that it had no tax disc. While the officers were checking Jack Whitney’s documents, Roberts panicked, and shot DC Wombell with a Luger pistol. When DS Head ran back towards the police car, Roberts shot him, too. Duddy sprang from the back of the van, brandishing an old Webley revolver, and joined Roberts by the police car where, together, they shot dead PC Fox. The two killers ran back and got into the van, which Whitney drove away at high speed. (Below) The murdered officers PC Fox, DC Wombwell and DS Head, and their funeral cortege.

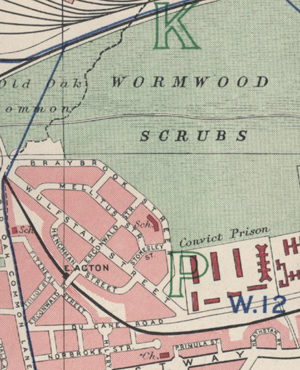

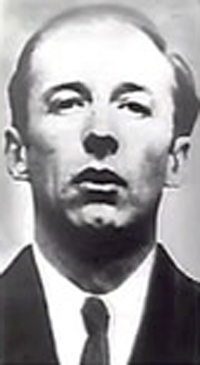

What became of the Shepherd’s Bush Killers? It should be noted that the murders took place in Acton, but possibly because the dead officers were based at Shepherd’s Bush, that name has stuck. John Duddy (left) died in Parkhurst prison on the Isle of Wight in 1981, at the age of 53, while Witney, possibly because he never fired a shot back in 1966, was released in 1991. He had eight years left to enjoy his freedom before death was to seek him out.

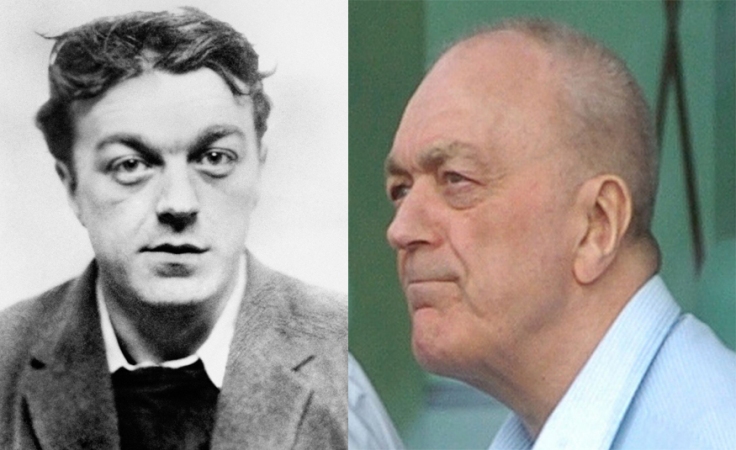

What became of the Shepherd’s Bush Killers? It should be noted that the murders took place in Acton, but possibly because the dead officers were based at Shepherd’s Bush, that name has stuck. John Duddy (left) died in Parkhurst prison on the Isle of Wight in 1981, at the age of 53, while Witney, possibly because he never fired a shot back in 1966, was released in 1991. He had eight years left to enjoy his freedom before death was to seek him out. of rent arrears. The two rowed over the money and daily household chores like washing up, Bristol Crown Court heard during Evans’ trial. Then, on August 15, 1999, Evans attacked Witney, (right) beating him around the head with a hammer. He grabbed him by the throat and Witney, who by then was quite frail, was throttled to death. Evans, aged 38, was found unanimously guilty, and given a life sentence.

of rent arrears. The two rowed over the money and daily household chores like washing up, Bristol Crown Court heard during Evans’ trial. Then, on August 15, 1999, Evans attacked Witney, (right) beating him around the head with a hammer. He grabbed him by the throat and Witney, who by then was quite frail, was throttled to death. Evans, aged 38, was found unanimously guilty, and given a life sentence.

THE 1999 SHOOTING OF A 16 YEAR-OLD BOY during an attempted burglary at a remote Norfolk farmhouse landed the unfortunate teenager in an early grave, and the farmer who fired the fatal shot was given a life sentence for murder.

THE 1999 SHOOTING OF A 16 YEAR-OLD BOY during an attempted burglary at a remote Norfolk farmhouse landed the unfortunate teenager in an early grave, and the farmer who fired the fatal shot was given a life sentence for murder.