Loren D Estleman’s Detroit PI Amos Walker is reassuringly traditional. It is close to a century since Dashiell Hammett introduced us to Sam Spade, and his legacy includes such gentlemen as Messrs Marlowe, Archer, Hammer, McGee and Spencer. I must add Janet Roger’s little known Newman (Shamus Dust 2019) into the mix, as that was the best non-Chandler PI novel I have ever read (and re-read).

Walker’s latest prospective client is Sage Holland, a woman dubbed by the tabloid press as The Black Widow. She has been tried and convicted of poisoning her husband, but on appeal, the conviction, for ‘Man One” ( first degree manslaughter) has been overturned on the grounds of prosecutorial misconduct. Now, she is being pursued and harassed by her late husband’s brother Greg, and she wants Walker’s help. He is partly convinced, despite this gem of an exchange:

“Why did Dave’s brother suspect you poisoned him?”

“He hates me. He always did.”

“He needed more than that to go on to arrive at poison. Ricin is only detectable during autopsy. Until then, it looks like a stroke or a heart attack.”

“Well, there were my first two husbands. They were about the same age as Dave when they died.”

Estleman never wastes an opportunity to remind us that Walker is a low budget operator:

“I tipped a hand toward the customer’s chair. She went to it, slinging a glance around the luxury accoutrements, the obsolete file cases, the Sunday school desk, a piece of reclaimed carpet from a five-year-old auto show. The much older and even more obsolete party, making himself uncomfortable behind the desk.”

Walker’s eye for detail is downbeat buy brutally accurate. He describes a neighbourhood loan shark:

“You had to look beyond the green plaid jacket and pre-tied bow tie, the baggy grin and the barber school haircut to see the dead eyes of an eel. And behind them, the brain that worked on a system of gears and pulleys like the machine on his desk.”

Walker enlists the help of his occasional assistant, Rafael Mesquino, an illegal immigrant who made it to America ‘with the bananas and tarantulas’. Mesquino fails to make a meeting. Worried, Walker finds the little man shot dead in his meagre lodgings, and begins to to comprehend just how much trouble Sage Holland is bringing into his life.We briefly meet Greg Holland when, fed up with being stalked, Walker invites him inside for a chat. The next time we see him, he is still in his car, but slumped over the steering wheel, dead from a small calibre gunshot to the head.

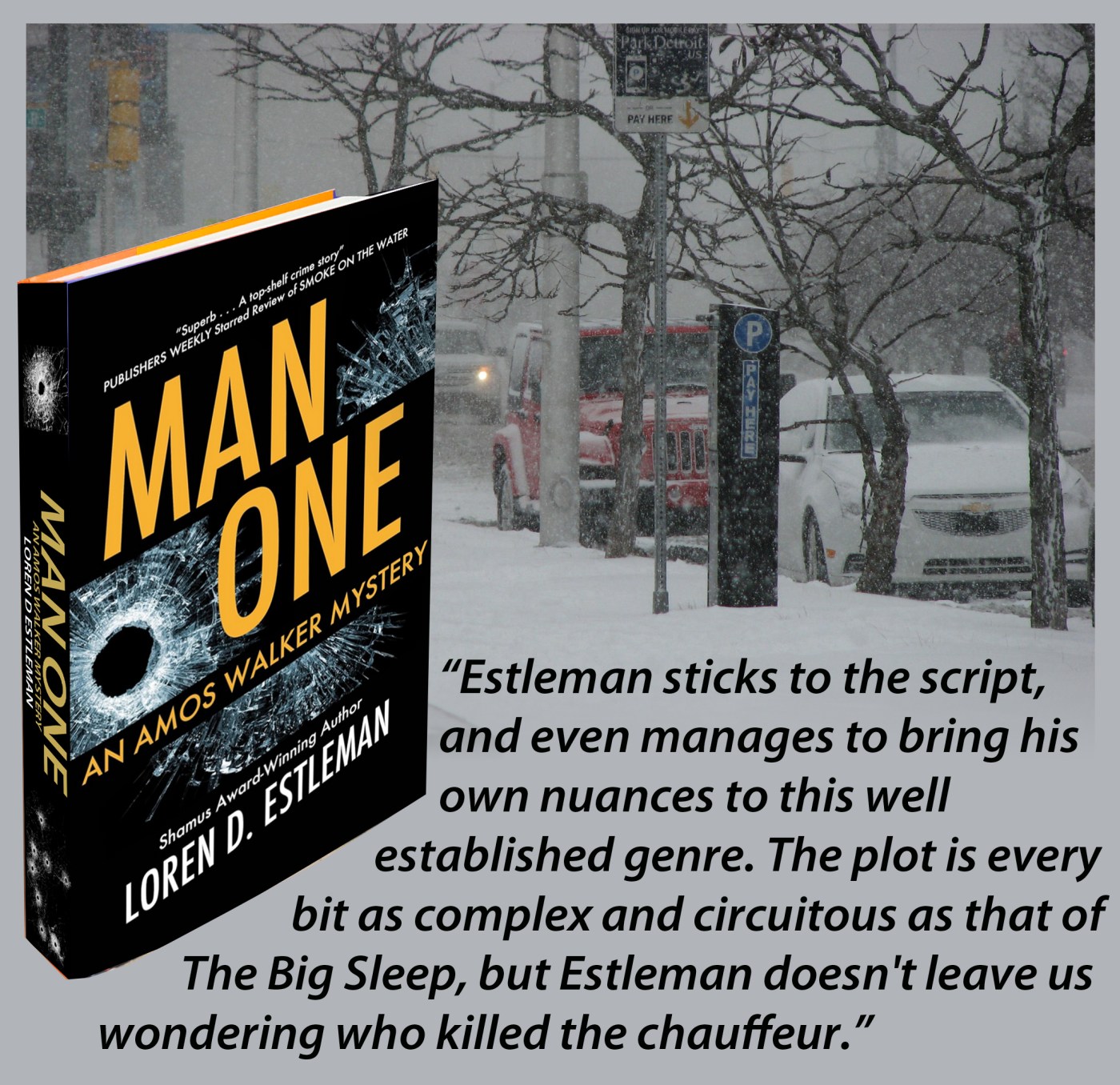

Following the furrow ploughed by writers such as Chandler and Robert B Parker should, in theory, be easy, but it has its pitfalls. Readers are well versed in the tropes, the seasoned dialogue and the cynical observations. Write something slightly out of tune, and you will be found out. Estleman sticks to the script, and even manages to bring his own nuances to this well established genre. The plot is every bit as complex and circuitous as that of The Big Sleep, but Estleman doesn’t leave us wondering who killed the chauffeur. Man One will be published by Severn House on 3rd February.