In 1859 The Lincolnshire village of Sibsey, just north of Boston, had a population of around 1400. The Sibsey Trader mill had yet to be built, but the railway had arrived in 1848. The 1851 census recorded the names of William Pickett, aged about 13, living with his parents and 9 siblings at Cherry Corner, Sibsey Northlands; Henry Carey, aged 18, lodging with Potter family at Sibsey Fenside, and someone who newspapers later described as ‘a notoriously bad character’, and William Stevenson, aged 57, an agricultural labourer. On the evening of Tuesday 16th March 1859, the lives of these men were to collide, with violent and fatal results for all three.

On the Tuesday morning, Stevenson had left home to go to market, and returned in the evening. He went to *The Ship inn in Sibsey Northlands which, as the name suggests, is a small settlement to the north of Sibsey. Stevenson’s home was in Stickney Westhouses, about a mile away from the pub and, after a convivial evening of drinking and smoking, he left The Ship at about 10.30 pm to walk the mile or so to his home. Westhouses is more or less a single track road these days and, on a winter’s night would still be bleak and forbidding. But this was a warm August night, and Stevenson, no doubt warmed from within by an evening drinking, would have had little fear of being out on his own on a lonely country road. He never reached his home.

*It is not clear if The Ship was a different pub from The Boat which is marked on old OS maps. The Ship was destroyed by fire in the late 1960s, and was owned by the Soulby, Son & Winch brewery.

Beside Westhouses Road ran a small drain, described in later court reports as ‘a sewer’. At a coroner’s inquest on Friday 19th August a local woman, Sarah Semper, testified:

What followed the grim discovery was recorded at the subsequent Coroner’s Inquest.

“A messenger was despatched for Dr. Moss, of Stickney, and Dr. Smith, of Sibsey, and another to the police, with information of the occurrence. The deceased’s son then commenced inquiries as to where his father had spent the previous evening, and on ascertaining that he had been at the Ship, proceeded there, and on going into the tap-room about seven o’clock in the morning, saw Carey and Pickett sitting there drinking beer; they had been there about hour: he sat opposite them for a minute or two and noticed spots of blood on their boots; he made no remark, but went and gave information of his suspicions to Sergeant Jones, who apprehended Sands ( a young man who was subsequently absolved from any blame) at half-past ten at his father’s house in bed; Pickett about half-past one, and Carey a little later in the the Ship. Sands stated that he slept in his father’s hovel, and on it being inspected it was ascertained that some one had slept there.“

“Pickett stated that he slept in his father’s stable, and Carey came to him at five o’clock in the morning, and they afterward, went to the Ship together. From the evidence of Sergeant Jones, and from inspection of the locality, it appears that the deceased had only gone a short distance after he left the public-house, when some person, crossed the road (which is a silt one, showing footmarks) from the opposite side to that where he was walking, and overtook him, and struck him a violent blow on the head, which felled him to the ground.”

“A struggle then ensued, and having been ultimately overpowered, after his pockets were emptied, the deceased was dragged to the side of the road, and thrown into a deep ditch: out of this he appeared to have scrambled, and got up the bank, and through the hedge, leaving traces of blood upon the bank and hedge, and got into an adjoining field. The murderers seeing their victim recovering, and doubtless fearing that he might identify them if he got away, crossed over the ditch by bridge a little higher up, and overtook the deceased in the field, where with hedge stakes they finished their bloody work, literally battering his skull and dashing out his brains, the ground about showing the following morning strong evidence of the murderous attack, patches of blood, pieces of skull and hair lying about They then carried the murdered man short distance and threw him over a hedge into the ditch where he was found.”

IN PART TWO

Trial, retribution, and a job for the Horncastle cobbler

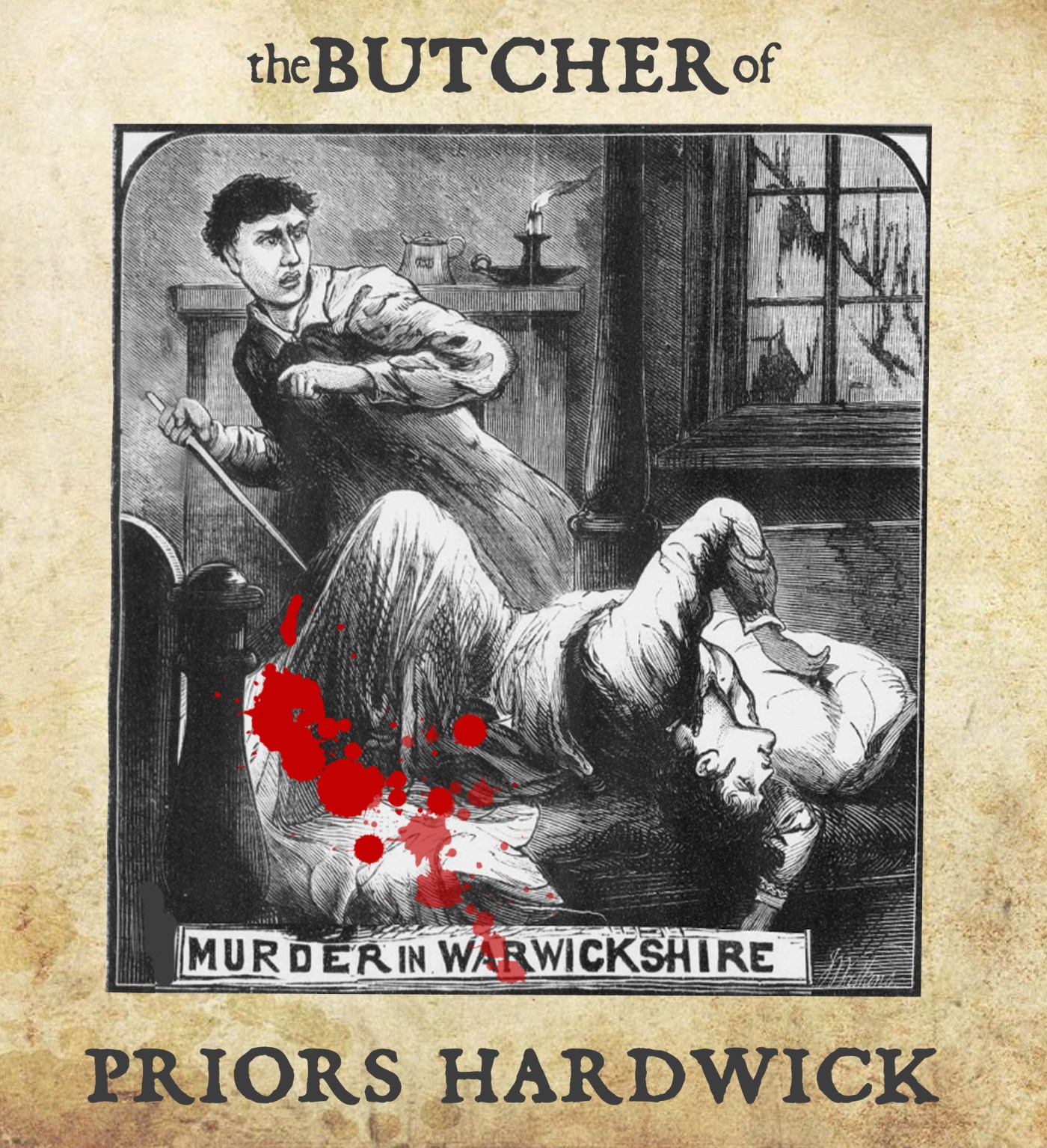

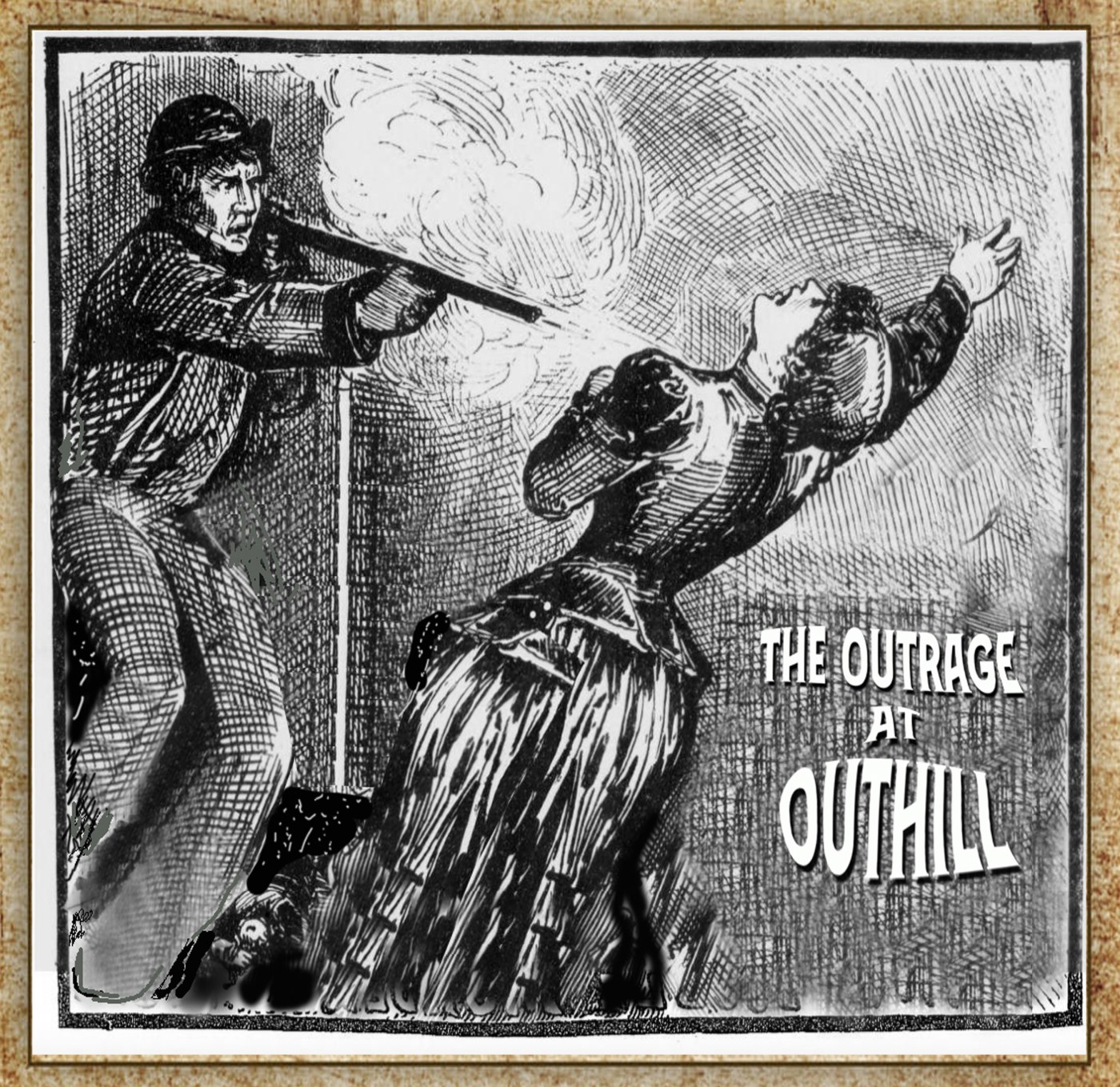

SO FAR: 23rd April, 1862, rural Warwickshire, and a 21 year old ploughman, George Gardner, employed by farmer Davis Edge at Outhill Farm, near Studley, has shot 24 year-old Sarah Kirby, employed by Edge as a domestic servant. Gardner’s peculiar state of mind before killing Sarah Kirby could almost be described as existential, in that it seemed to recognise neither logic nor the law – just his own obsession. He did, however, seem to have acknowledged the presence of chance. He had been uncertain that morning about killing Sarah Kirby, so he adopted a rural version of tossing a coin. Ploughmen used a hand-tool known as a “spud”. It was basically a flat blade, usually mounted on a wooden handle, (left} and used for clearing earth from the blades of the plough. Gardner decided to toss the tool in the air, and if it landed blade first, then Sarah Kirby would die. It did, and so did the young woman.

SO FAR: 23rd April, 1862, rural Warwickshire, and a 21 year old ploughman, George Gardner, employed by farmer Davis Edge at Outhill Farm, near Studley, has shot 24 year-old Sarah Kirby, employed by Edge as a domestic servant. Gardner’s peculiar state of mind before killing Sarah Kirby could almost be described as existential, in that it seemed to recognise neither logic nor the law – just his own obsession. He did, however, seem to have acknowledged the presence of chance. He had been uncertain that morning about killing Sarah Kirby, so he adopted a rural version of tossing a coin. Ploughmen used a hand-tool known as a “spud”. It was basically a flat blade, usually mounted on a wooden handle, (left} and used for clearing earth from the blades of the plough. Gardner decided to toss the tool in the air, and if it landed blade first, then Sarah Kirby would die. It did, and so did the young woman.

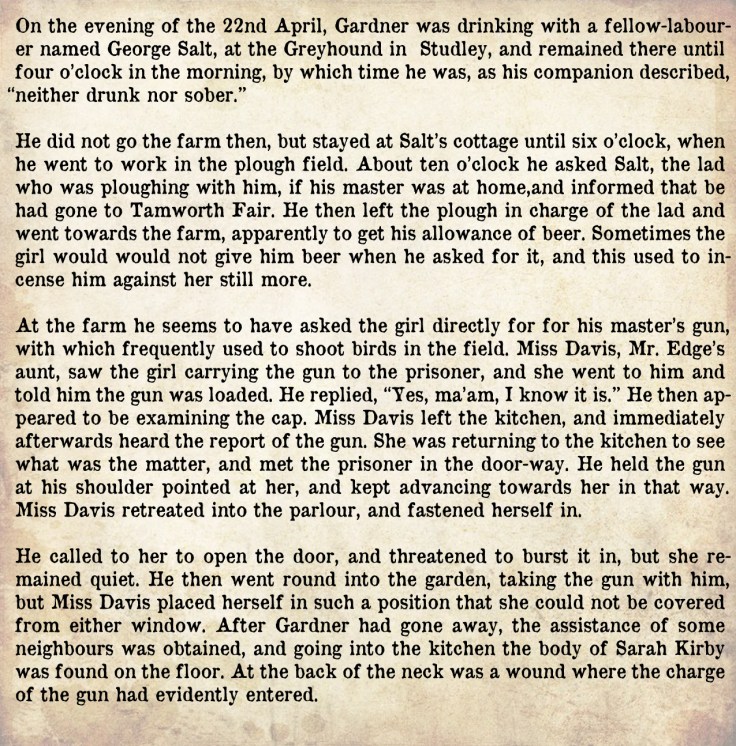

Gardner had one further misfortune. His executioner was none other than George Smith (right), a former criminal and noted drunk, known – with rough humour – as The Dudley Throttler. This was to be a public execution, and a perfectly respectable form of cheap entertainment at the time. A reporter described the scene:

Gardner had one further misfortune. His executioner was none other than George Smith (right), a former criminal and noted drunk, known – with rough humour – as The Dudley Throttler. This was to be a public execution, and a perfectly respectable form of cheap entertainment at the time. A reporter described the scene: