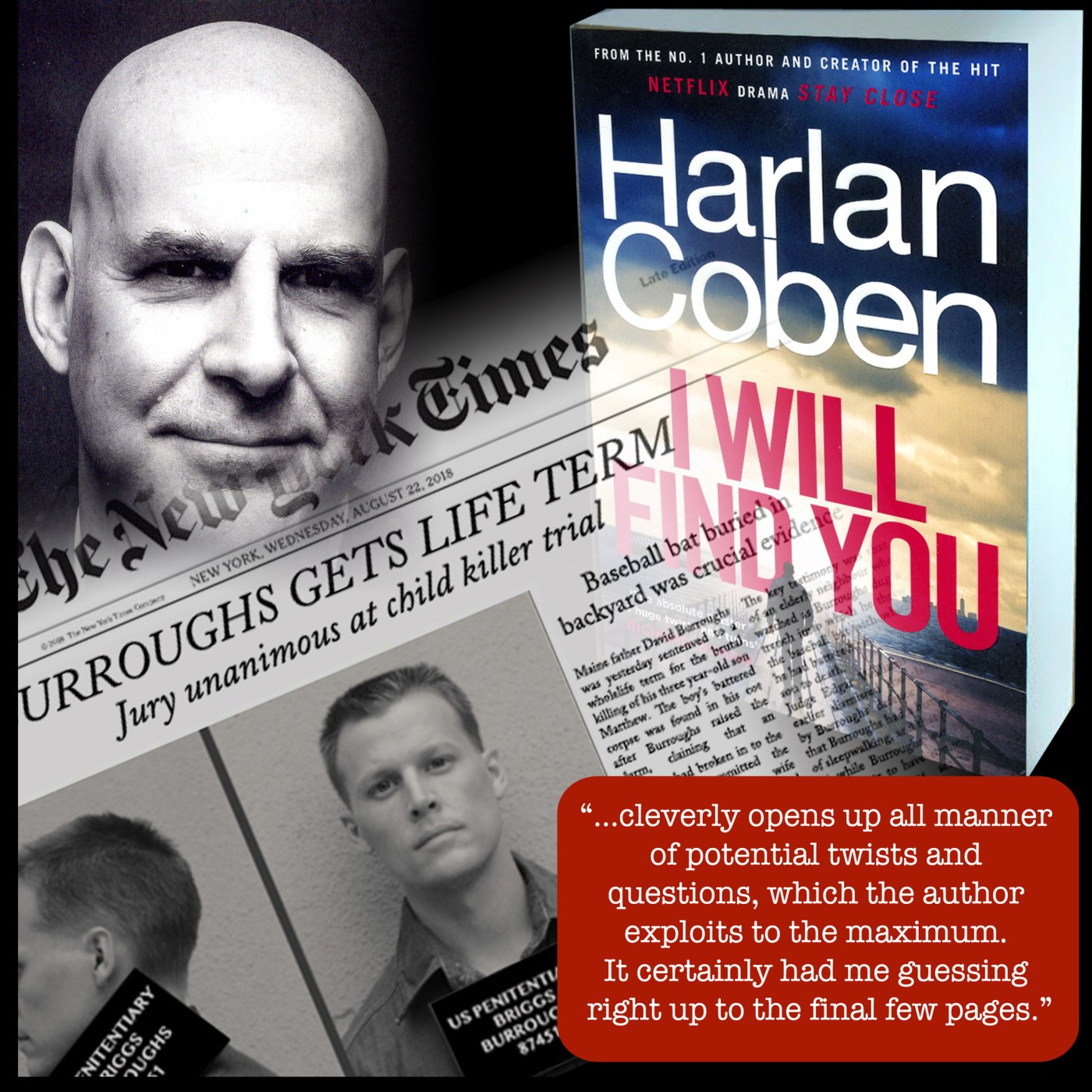

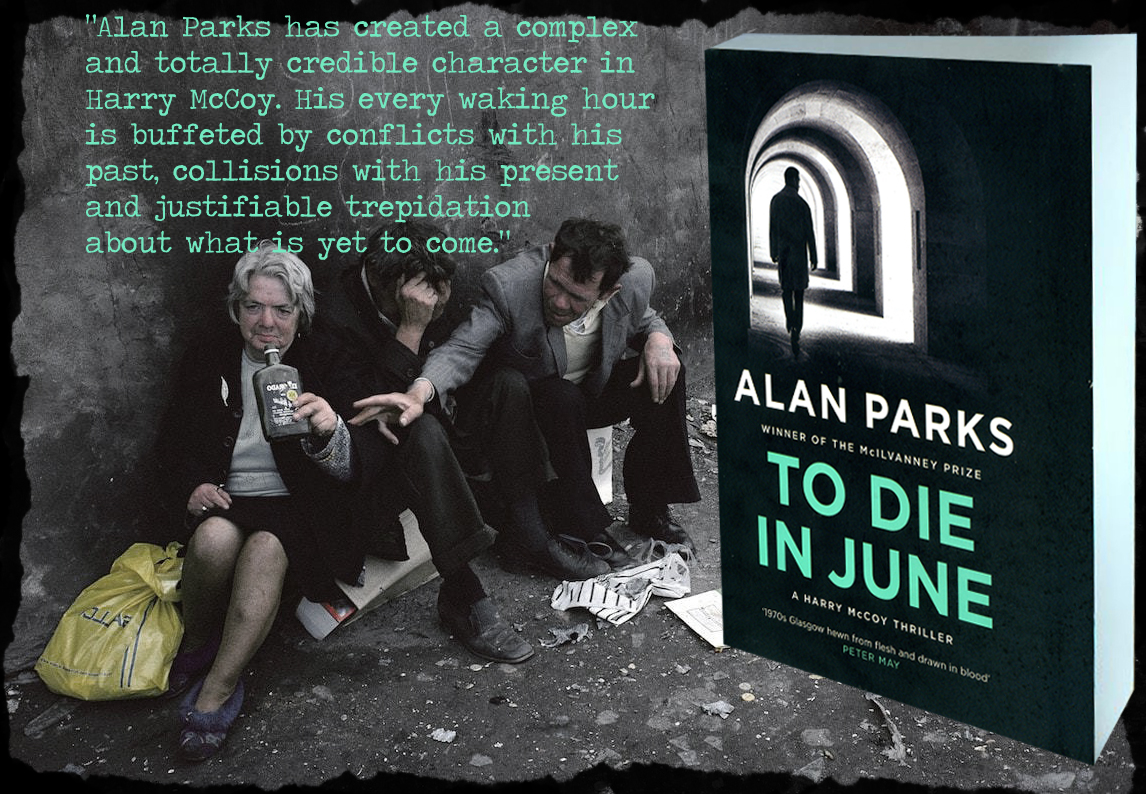

Alan Parks (left) introduced us to Glasgow cop Harry McCoy in 2018 with Bloody January, and he has been resolutely working through the months with succeeding novels. Fictional Detective Inspectors in British crime fiction are many and varied. You would certainly need a fair sized village hall to seat them comfortably were they all to meet, so what about Harry McCoy? He has a fairly dark back-story. He was in and out of care institutions as a child. His mother is long dead, and his father – never the most consistent of parents – has now abandoned any sense of normality and is a homeless alcoholic. Through childhood connections – both were in care – he is connected to underworld boss Stevie Cooper. While not exactly in his pay, McCoy owes his old friend big-time, due to incidents in their shared past.

Alan Parks (left) introduced us to Glasgow cop Harry McCoy in 2018 with Bloody January, and he has been resolutely working through the months with succeeding novels. Fictional Detective Inspectors in British crime fiction are many and varied. You would certainly need a fair sized village hall to seat them comfortably were they all to meet, so what about Harry McCoy? He has a fairly dark back-story. He was in and out of care institutions as a child. His mother is long dead, and his father – never the most consistent of parents – has now abandoned any sense of normality and is a homeless alcoholic. Through childhood connections – both were in care – he is connected to underworld boss Stevie Cooper. While not exactly in his pay, McCoy owes his old friend big-time, due to incidents in their shared past.

We are in the summer of 1975 so, in one sense this a historical novel, with many little period features that the author has to get right. No internet, computers or mobile phones, obviously, but early on in the story Parks sets the scene beautifully. McCoy has a celebrity girlfriend – a famous actress – and they are together at an showbiz awards function in the company of a young Billy Connolly, Stanley Baxter, Marie McDonald McLaughlin Lawrie (Google her) and Hamish Imlach. For those not versed in Scottish entertainers, Parks has Michael Aspel overseeing the evening.

McCoy has been transferred from his usual base to the insalubrious district of Possil, an area renowned for crime and deprivation. There is a purpose behind the move. McCoy’s boss, Chief Inspector Murray, believes that a group of detectives at the Possil station are corrupt, and he wants McCoy to infiltrate the cabal. Before McCoy can get close to the bent coppers, two urgent cases demand his attention. First, a vagrant is found dead, foaming at the mouth from having imbibed some kind of toxic drink. McCoy attends the scene, praying that the victim is not his dad. It isn’t, but the blasé dismissal of the case by the ‘experts’ as “just another alkie drank himself into an early grave” annoys him, and he senses something more sinister.

Then, a distraught woman presents herself at the station telling him that her young son has been abducted. Understandably, McCoy takes the woman at her word, and hits the panic button, with ensuing door-to-door, enquiries, blue lights flashing everywhere, and all leave cancelled. The woman then has some kind of fit and is hospitalised. When McCoy visits the home, and talks to the woman’s husband, the Reverend West, he is told that there is no son – never was – and that his wife has been suffering with sever mental health issues for some years. West is the pastor at an obscure fundamentalist church, The Church of Christ’s Suffering.

When Mrs West throws herself to her death from a bridge, and more homeless men are found dead, McCoy hardly knows which way to turn. Added into the mix of his misery is that his old chum Stevie Cooper is about to initiate a turf war with a rival gangster, and expects McCoy to play his part. The plot twists this way and that, and there is a final hairpin bend which runs off the road anyone who is hoping for a warm and comfortable outcome to to this case for Harry McCoy.

lan Parks has created a complex and totally credible character in Harry McCoy. His every waking hour is buffeted by conflicts with his past, collisions with his present and justifiable trepidation about what is yet to come. To Die In June was published by Canongate on 25th May.

Keith Dixon’s Porthaven is a fictional town on England’s south coast. It doesn’t seem woke or disfunctional enough to be Brighton, maybe neither big nor rough enough to be Portsmouth or Southampton, so it’s maybe a mix of all three, seasoned with a dash of Newhaven and Peacehaven. Inspector Walter Watts is a Porthaven copper. He is middle-aged, deeply cynical, overweight, and a man certainly not at ease with himself – or many others – but a very good policeman. When a young woman, later identified as Cheryl Harris, is found murdered on a piece of waste ground, the only thing Watts accomplishes on his visit to the scene is that his sarcastic exchanges with a female CSI officer result in in an official complaint, and him being moved off the case. From the sidelines, Watts knows that whoever killed the young woman was definitely trying to pass on a message. The woman’s face has been obliterated by a concrete slab, with her mobile ‘phone jammed into what was left of her mouth.

Keith Dixon’s Porthaven is a fictional town on England’s south coast. It doesn’t seem woke or disfunctional enough to be Brighton, maybe neither big nor rough enough to be Portsmouth or Southampton, so it’s maybe a mix of all three, seasoned with a dash of Newhaven and Peacehaven. Inspector Walter Watts is a Porthaven copper. He is middle-aged, deeply cynical, overweight, and a man certainly not at ease with himself – or many others – but a very good policeman. When a young woman, later identified as Cheryl Harris, is found murdered on a piece of waste ground, the only thing Watts accomplishes on his visit to the scene is that his sarcastic exchanges with a female CSI officer result in in an official complaint, and him being moved off the case. From the sidelines, Watts knows that whoever killed the young woman was definitely trying to pass on a message. The woman’s face has been obliterated by a concrete slab, with her mobile ‘phone jammed into what was left of her mouth. Watts was brought up by his father – and in boarding schools – after his mother left the home. There has been no contact with her from that day to this, until he receives a message from the desk sergeant at Porthaven ‘nick’ simply saying that his mother had ‘phoned, and would he call her back on the number provided. This thread provides an interesting and complex counterpoint to the police investigation into the killing of Cheryl Harris. It also allows Keith Dixon (right) to better define Watts as a person; on the one hand he is aloof, selfish, socially abrasive and enjoys showing his mental superiority; on the other, he is vulnerable, unsure, and shaped by a childhood lacking conventional affection.

Watts was brought up by his father – and in boarding schools – after his mother left the home. There has been no contact with her from that day to this, until he receives a message from the desk sergeant at Porthaven ‘nick’ simply saying that his mother had ‘phoned, and would he call her back on the number provided. This thread provides an interesting and complex counterpoint to the police investigation into the killing of Cheryl Harris. It also allows Keith Dixon (right) to better define Watts as a person; on the one hand he is aloof, selfish, socially abrasive and enjoys showing his mental superiority; on the other, he is vulnerable, unsure, and shaped by a childhood lacking conventional affection.

Some writers who have authored different series occasionally allow the main characters to meet each other, provided that they are contemporaries, of course. I’m pretty sure that Michael Connolly has allowed Micky Haller to bump into Harry Bosch, while Sunny Randall and Jesse Stone certainly knew each other in their respective series by Robert J Parker. Did Spenser ever join them in a (chaste) threesome? I don’t remember. John Lawton’s magnificent Fred Troy series ended with Friends and Traitors (2017), and since then he has been writing the Joe Wilderness books, of which this is the fourth. I can report, with some delight, that in the first few pages we not only meet Fred, but also Meret Voytek, the tragic heroine of A Lily of the Field, and her saviour – Fred’s sometime lover and former wife, Larissa Tosca. As an aside, for me A Lily of the Field is not only the best book John Lawton has ever written, but the most harrowing and heartbreaking account of Auschwitz ever penned. Click the link below to read more.

Some writers who have authored different series occasionally allow the main characters to meet each other, provided that they are contemporaries, of course. I’m pretty sure that Michael Connolly has allowed Micky Haller to bump into Harry Bosch, while Sunny Randall and Jesse Stone certainly knew each other in their respective series by Robert J Parker. Did Spenser ever join them in a (chaste) threesome? I don’t remember. John Lawton’s magnificent Fred Troy series ended with Friends and Traitors (2017), and since then he has been writing the Joe Wilderness books, of which this is the fourth. I can report, with some delight, that in the first few pages we not only meet Fred, but also Meret Voytek, the tragic heroine of A Lily of the Field, and her saviour – Fred’s sometime lover and former wife, Larissa Tosca. As an aside, for me A Lily of the Field is not only the best book John Lawton has ever written, but the most harrowing and heartbreaking account of Auschwitz ever penned. Click the link below to read more.

Without giving the game away, it is in Brother Dominic’s previous life where the clues are to be found, but answers don’t come easy for Cross and Ottey. Although there was a very clever plot twist involving the identity of the killer, I was far more involved with George Cross as a person than wondering who murdered Brother Dominic.The relationship between Cross and his father, the discombobulating effect of the re-emergence of his mother – lost to him since she left the family home when he was five – and his attraction to the unambiguous world of order, silence and simplicity of Dominic’s fellow monks, all contribute to the power of this compelling read.

Without giving the game away, it is in Brother Dominic’s previous life where the clues are to be found, but answers don’t come easy for Cross and Ottey. Although there was a very clever plot twist involving the identity of the killer, I was far more involved with George Cross as a person than wondering who murdered Brother Dominic.The relationship between Cross and his father, the discombobulating effect of the re-emergence of his mother – lost to him since she left the family home when he was five – and his attraction to the unambiguous world of order, silence and simplicity of Dominic’s fellow monks, all contribute to the power of this compelling read.