The opening part of this book, in geo-political terms, is gloriously old fashioned. Istambul, with its reputation as being the place where east meets west, home of mysterious Levantine traders and treacherous stateless misfits has long since been pensioned off, at least in the world of crime and espionage fiction. It is worth remembering, though, that it was the starting point for Bond’s adventures in From Russia With Love when it was published in 1957, and was still thought to have a suitable ambience when the film was released in 1963.

Charles Latimer is an English academic who has found that writing thrillers is much more to his liking (and that of his bank manager) than lengthy tracts on political and economic trends in nineteenth century Europe. While in Istanbul he is invited to a house party where he meets Colonel Haki, an officer in some un-named sinister police force. Improbably, Haki is a fan of Latimer’s novels and, when they become better acquainted, Haki reveals a current real-life mystery he is investigating. The corpse of a man known only as Dimitrios – once a big player in the espionage world of the Levant and The Balkans – is fished out of the sea. Having attended the post mortem, Latimer decides to investigate just who Dimitrios was, and how he came to end up as he did.

Published on the eve of world war two, when previous atrocities would be dwarfed in scale, the novel reminds us of the horrors which took place in the region after the Armistice. The brutal civil war between Turkey and Greece, with the destruction of Smyrna in 1922, the Armenian genocide, and a succession of coups d’états in Bulgaria had left the region rife with intrigue and foreign meddling. By the late 1930s, Europe was desperately ill at ease with itself. Latimer observes:

“So many years. Europe in labour had through its pain seen for an instant a new glory, and then had collapsed to welter again in the agonies of war and fear. Governments had risen and fallen: men and women had worked, had starved, had made speeches, had thought, had been tortured and died. Hope had come and gone, a fugitive in the scented bosom of illusion.”

As he criss-crosses Europe via Athens, Sofia, Geneva, Paris – by train, naturally – Latimer is drawn into the world of a mysterious man known only as Mr Peters, memorably described thus:

“Then Latimer saw his face and forgot about the trousers. There was the sort of sallow shapelessness about it that derives from simultaneous overeating and under sleeping. From above two heavy satchels of flesh peered a pair of blue, bloodshot eyes that seemed to the permanently weeping. The nose was rubbery and indeterminate. It was the mouth that gave the face expression. The lips were pallid and undefined, seeming thicker than they really were. Pressed together over unnaturally white and regular false teeth, they were set permanently in a saccharine smile.”

The 1944 film of the book took many liberties with the story and, bizarrely, changed the clean-living, rather prim Charles Latimer into a Dutch novelist named Cornelius Leyden, and then compounded the felony by casting Peter Lorre in the role. What they didn’t get wrong, however, was in re-imagining Mr Peters. Check the quote above, and if it isn’t Sydney Greenstreet to the proverbial ‘T’, then I will change my will and donate my worldly wealth to The Jeremy Corbyn Appreciation Society. In his travels, Latimer also meets a rather down-at-heel nightclub manager called La Prevesa:

“The mouth was firm and good-humoured in the loose, raddled flesh about it, but the eyes were humid with sleep and the carelessness of sleep. They made you think of things you had forgotten, of clumsy gilt hotel chairs strewn with discarded clothes and of grey dawn light slanting through closed shutters, of attar of roses and of the musty smell of heavy curtains on brass rings, of the sound of the warm, slow breathing of a sleeper against the ticking of a clock in the darkness”

Quite near the end of the book, Ambler drops a plot bombshell which not only damages Latimer’s own sense of being able to spot a lie when he sees one, but puts him next in line for a drug-dealer’s bullet. He is in Paris, but this is not the city as envisaged by, apparently, Victor Hugo:

“Breathe Paris in. It nourishes the soul.”

Latimer sees a rather different city:

“As his taxi crossed the bridge back to Île de la Cité, he saw for a moment a panorama of low, black clouds moving quickly in the chill, dusty wind. The long facade of the houses on the Quai de Corse was still and secretive. It was as if each window concealed a watcher. There seemed to be few people about. Paris, in the late autumn afternoon, had the macabre formality of a steel engraving.”

With this book, Ambler created the anvil on which the great spy novels of the final decades of the Twentieth Century were beaten out. As good as they were, neither Le Carré nor Deighton bettered his use of language, and in this relatively short novel, just 264 pages, Ambler set the Gold Standard. This latest edition of the novel is published by Penguin and is available now.

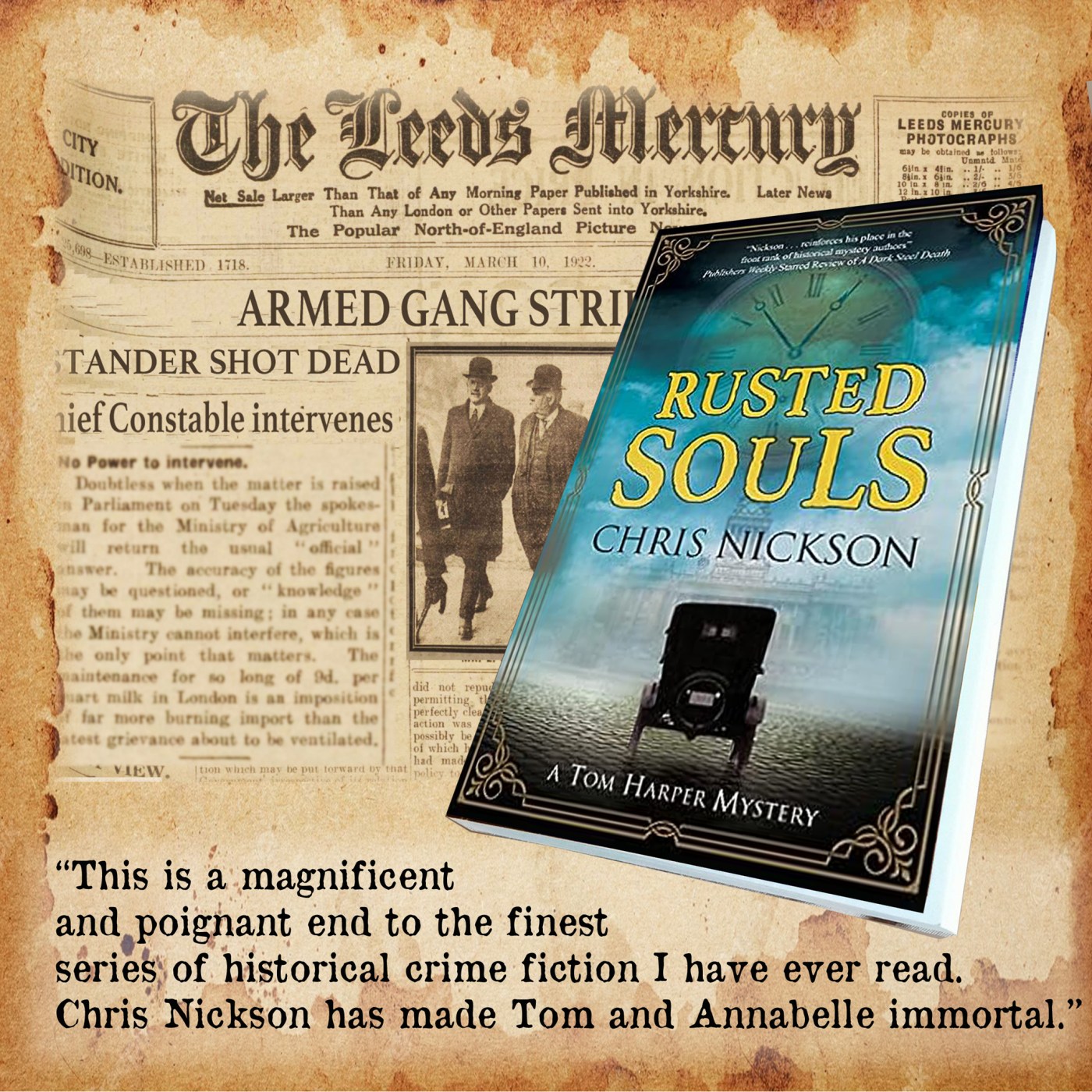

Leeds, March 1920. Tom Harper is Chief Constable of the City force and, with just six weeks until his retirement, he is dearly hoping for a quiet ride home for the final furlong of what has been a long and distinguished career. His hopes are dashed, however, when he is summoned to the office of Alderman Ernest Thompson, the combative, blustering – but very powerful – leader of the City Council. Thompson has one last task for Harper, and it is a very delicate one. The politician has fallen a trap that is all too familiar to many elderly men of influence down the years. He has, shall we say, been indiscreet with a beautiful but much younger woman, Charlotte Radcliffe. Letters that he foolishly wrote to her have “gone missing” and now he has an anonymous note demanding money – or else his reputation will be ruined. He wants Harper to solve the case, but keep everything completely off the record. Grim-faced, Harper has little choice but to agree. It is due to Thompson’s support and encouragement that he is ending his career as Chief Constable, with a comfortable pension and an untarnished reputation. He chooses a small group of trusted colleagues, swears them to secrecy, and sets about the investigation.

Leeds, March 1920. Tom Harper is Chief Constable of the City force and, with just six weeks until his retirement, he is dearly hoping for a quiet ride home for the final furlong of what has been a long and distinguished career. His hopes are dashed, however, when he is summoned to the office of Alderman Ernest Thompson, the combative, blustering – but very powerful – leader of the City Council. Thompson has one last task for Harper, and it is a very delicate one. The politician has fallen a trap that is all too familiar to many elderly men of influence down the years. He has, shall we say, been indiscreet with a beautiful but much younger woman, Charlotte Radcliffe. Letters that he foolishly wrote to her have “gone missing” and now he has an anonymous note demanding money – or else his reputation will be ruined. He wants Harper to solve the case, but keep everything completely off the record. Grim-faced, Harper has little choice but to agree. It is due to Thompson’s support and encouragement that he is ending his career as Chief Constable, with a comfortable pension and an untarnished reputation. He chooses a small group of trusted colleagues, swears them to secrecy, and sets about the investigation.

I must confess to not having read anything by Robert Goddard (left) for a few years. Back in the day I enjoyed his James Maxted trilogy, which comprised The Ways of the World (2013), The Corners of the Globe (2014) and The Ends of The Earth (2015), which focused on a young former RAF pilot and his involvement in the political fallout in Europe after the Versailles Conference ended in 1920. I reviewed his standalone novel

I must confess to not having read anything by Robert Goddard (left) for a few years. Back in the day I enjoyed his James Maxted trilogy, which comprised The Ways of the World (2013), The Corners of the Globe (2014) and The Ends of The Earth (2015), which focused on a young former RAF pilot and his involvement in the political fallout in Europe after the Versailles Conference ended in 1920. I reviewed his standalone novel

Catherine Ryan Howard shines an unforgiving light on the way in which the media treats the parents and family of women or children who have been abducted or murdered. Jennifer Gold was the youngest of the three missing women. She was conventionally beautiful, a scholar, high achiever and photogenic. Likewise her mother Margaret is polished, well groomed and an assured media performer. By contrast, Tana Meehan – the first woman to be abducted – was overweight and something of a wreck of a person, having left her husband to go home to live with her elderly and ill parents. Nicki O’Sullivan, or so it was reported, had been last seen staggering around on the pavement after drinking too much at a party.

Catherine Ryan Howard shines an unforgiving light on the way in which the media treats the parents and family of women or children who have been abducted or murdered. Jennifer Gold was the youngest of the three missing women. She was conventionally beautiful, a scholar, high achiever and photogenic. Likewise her mother Margaret is polished, well groomed and an assured media performer. By contrast, Tana Meehan – the first woman to be abducted – was overweight and something of a wreck of a person, having left her husband to go home to live with her elderly and ill parents. Nicki O’Sullivan, or so it was reported, had been last seen staggering around on the pavement after drinking too much at a party.