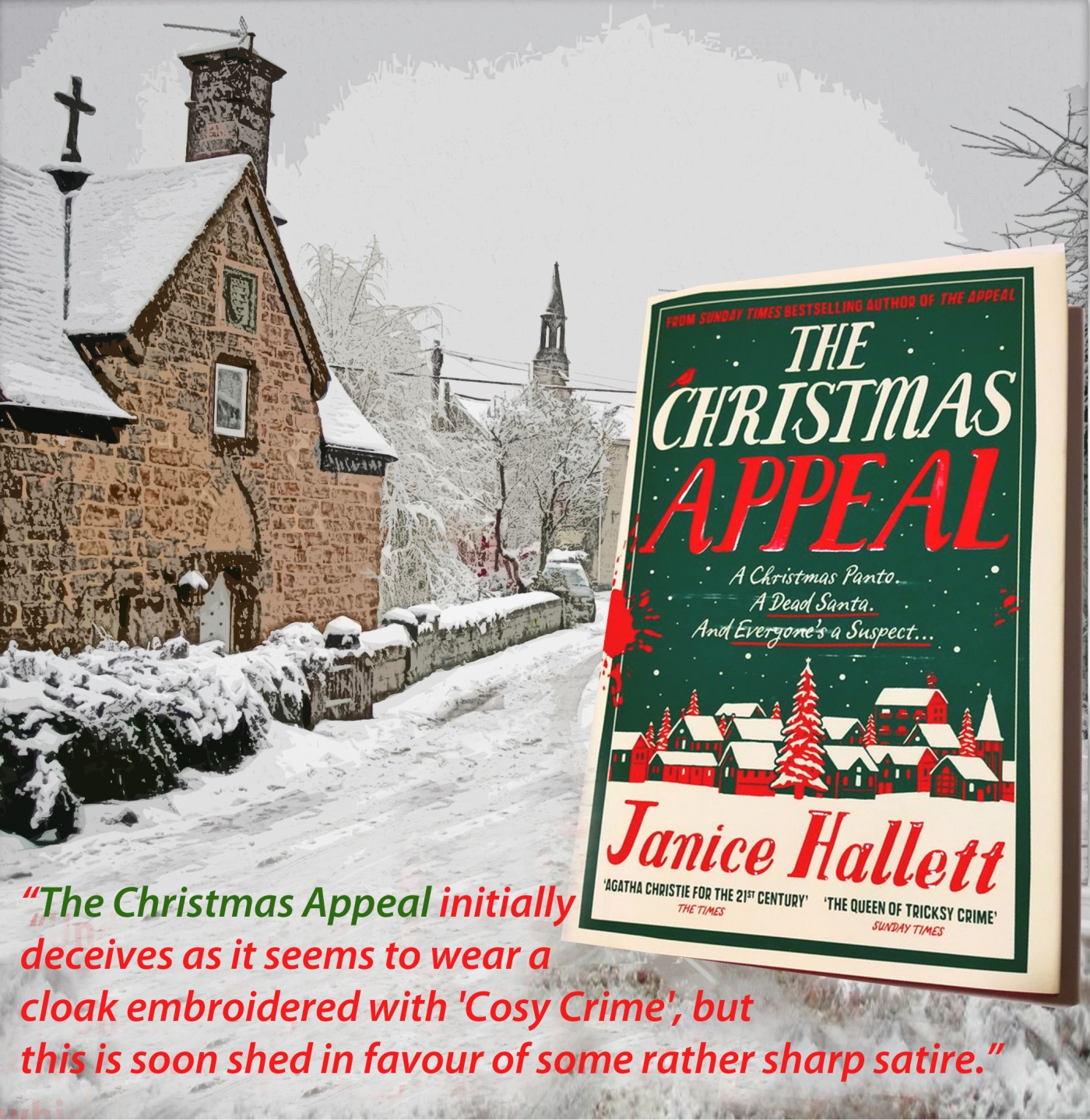

Janice Hallett (left) invites us to return to the idyllic village of Lower Lockwood, where her book The Appeal (2021) was set. Then, law students Charlotte Holroyd and Femi Hassan solved a particularly nasty murder but, goodness me, murder seems to haunt Lower Lockwood rather as it does the unfortunate community of Midsomer, and so they are back again when another corpse is found, threatening the production of the annual village panto. Was ever a production of Jack and The Beanstalk so fraught with difficulties?

Our two sleuths (now fully qualified) spend little time on their hands and knees with magnifying glasses looking for minute physical traces which may betray the assailant; rather, they sit in front of their smartphones, perusing emails, WhatsApp messages, texts and other communications floating around in the digital ether. The clues are all there and, unlike the ancient trope of detectives trying to read messages from letters hastily burnt in fireplaces, these words can never be totally erased.

This novella is inventively set up with little or no conventional narrative and makes extensive use of graphics representing WhatsApp messages (above) and emails which are now known as ’round-robins’. Being an old pedant, I have to say that this is a misuse of the expression, as the dictionary says:

The term has come to be used to describe emails cc-d to multiple recipients, and those awful little printed slips inside Christmas cards telling friends (not for much longer, if I get them) all the wonderful things that have been happening to the sender’s family since the last Christmas card. Janice Hallett, by the way, makes fun of these dreadful things from the word go.

But I digress. You will either love the set up of the story, or hate it. I enjoyed it while it lasted – just 187 pages – but I suspect it wouldn’t work in a longer book.

The story begins when Charlotte and Femi receive a massive folder (all digital of course) of evidence from their former mentor, Roderick Tanner KC. The folder contains transcriptions of police interviews and copies of all communications between those involved when a long-dead body in a Santa Suit was found hidden in a giant beanstalk prop – made mostly of wood, papier–mâché and, heaven forfend, possible traces of asbestos. The beanstalk was constructed years previously for a production of the play, and so this is the coldest of cold cases. The mystery is solved as Charlotte and Femi pick up the hints from the emails, texts and messages, but along the way, Janice Hallett takes the you-know-what out of some of the more insufferable pretensions in modern society (below).

The Christmas Appeal initially deceives as it seems to wear a cloak embroidered with ‘Cosy Crime’, but this is soon shed in favour of some rather sharp satire. It has wit, charm and flair and is published by Viper. It is available now.

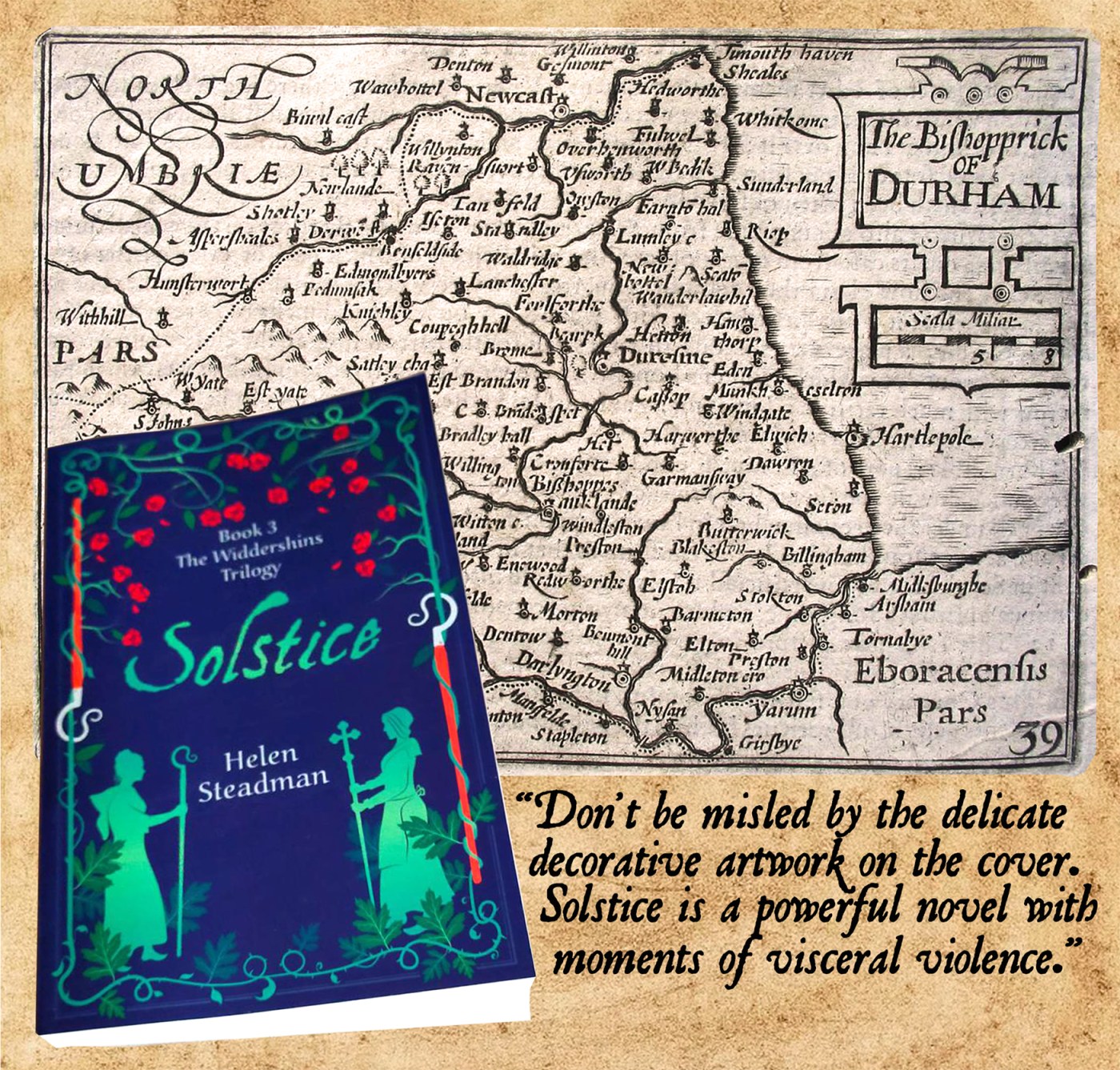

Widdershins, by the way is a strange word. Some say it was German, others say it originated in Scotland. It translates as

Widdershins, by the way is a strange word. Some say it was German, others say it originated in Scotland. It translates as

Brat Farrar is an ingenious invention. He is an orphan, and even his name is the result of administrative errors and poor spelling. He has been around the world trying to earn a living in such exotic locations as New Mexico, but has ended up in London, virtually penniless and becomes an easy mark for a chancer like Alec Loding. He is initially reluctant to take art in the scheme, but with Loding’s meticulous coaching – and his own uncanny resemblance to the late Patrick – he convinces the Ashbys that he is the real thing. But – and it is a very large ‘but’ – Brat senses that Simon Ashby has his doubts, and they soon reach a disturbing kind of equanimity. Each knows the truth about the other, but dare not say. The author’s solution to the conundrum is elegant, and the endgame is both gripping and has a sense of natural justice about it.

Brat Farrar is an ingenious invention. He is an orphan, and even his name is the result of administrative errors and poor spelling. He has been around the world trying to earn a living in such exotic locations as New Mexico, but has ended up in London, virtually penniless and becomes an easy mark for a chancer like Alec Loding. He is initially reluctant to take art in the scheme, but with Loding’s meticulous coaching – and his own uncanny resemblance to the late Patrick – he convinces the Ashbys that he is the real thing. But – and it is a very large ‘but’ – Brat senses that Simon Ashby has his doubts, and they soon reach a disturbing kind of equanimity. Each knows the truth about the other, but dare not say. The author’s solution to the conundrum is elegant, and the endgame is both gripping and has a sense of natural justice about it. Josephine Tey was one of the pseudonyms of Elizabeth MacKintosh (1896-1952) Her play, Richard of Bordeaux (written as Gordon Daviot) was celebrated in its day, and was produced by – and starred – John Gielgud. She never married, but a dear friend – perhaps an early romantic attachment – was killed on the Somme in 1916. She remained an enigma – even to friends who thought themselves close – throughout her life. Her funeral was reported thus:

Josephine Tey was one of the pseudonyms of Elizabeth MacKintosh (1896-1952) Her play, Richard of Bordeaux (written as Gordon Daviot) was celebrated in its day, and was produced by – and starred – John Gielgud. She never married, but a dear friend – perhaps an early romantic attachment – was killed on the Somme in 1916. She remained an enigma – even to friends who thought themselves close – throughout her life. Her funeral was reported thus:

The song, which has many more verses, was written as a sarcastic response to a statement made – allegedly by the MP Nancy Astor – criticising the 8th Army for not being part of the D Day landings in June 1944. Historian and broadcaster James Holland (left) has written an account of the Italian Campaign from the invasion of the mainland in September 1943 until the year’s end and, having read it, I can only think that the bitterness of the 8th Army men was more than justified.

The song, which has many more verses, was written as a sarcastic response to a statement made – allegedly by the MP Nancy Astor – criticising the 8th Army for not being part of the D Day landings in June 1944. Historian and broadcaster James Holland (left) has written an account of the Italian Campaign from the invasion of the mainland in September 1943 until the year’s end and, having read it, I can only think that the bitterness of the 8th Army men was more than justified.

The legend of King John’s lost treasure is an intriguing one, and Diane Calton Smith (left) cleverly reimagines it in her novel In The Wash. I am not normally a fan of split time narratives, but she does it beautifully here, with the events of October 1216 being mirrored perfectly by a present day story beginning, also, in October. Perhaps ‘mirror’ is not the best metaphor – the two stories are more like a melody and its counterpoint in music, each complementing the other. In 1216 we meet Rufus, a young clerk under the tutelage of Father Leofric, a priest at Wisbech Castle, and the entire establishment is waiting for the arrival of King John, who is to make a break in his journey from Bishop’s Lynn to Newark. In present day Wisbech, Monica Kerridge is the curator of The Poet’s House Museum, an establishment dedicated to the life and work of celebrated Georgian poet Joshua Ambrose.

The legend of King John’s lost treasure is an intriguing one, and Diane Calton Smith (left) cleverly reimagines it in her novel In The Wash. I am not normally a fan of split time narratives, but she does it beautifully here, with the events of October 1216 being mirrored perfectly by a present day story beginning, also, in October. Perhaps ‘mirror’ is not the best metaphor – the two stories are more like a melody and its counterpoint in music, each complementing the other. In 1216 we meet Rufus, a young clerk under the tutelage of Father Leofric, a priest at Wisbech Castle, and the entire establishment is waiting for the arrival of King John, who is to make a break in his journey from Bishop’s Lynn to Newark. In present day Wisbech, Monica Kerridge is the curator of The Poet’s House Museum, an establishment dedicated to the life and work of celebrated Georgian poet Joshua Ambrose.