The novel starts in London, March 2020 and, like millions of other people, the Mountford family are sitting watching the news, and there is only one item – The Lockdown. Stringent rules about association and movement have been imposed, but Tony Mountford is nothing if not a quick thinker. He and his family are lucky. They own a holiday cottage in the south of England, and he decides on the spur of the moment to pile everyone and everything into the car and head south. They avoid police patrols, and arrive safely at the cottage. Across Britain, and the rest of Europe, a million nightmares are being enacted as the Covid death toll rises, but for the Mountfords, their nightmare is only just beginning.

The cottage, although it has been brought up to date after a fashion, is ancient: it has a resident ghost, or other-worldly presence; when sensed, it has been entirely benign, to the extent that it is mentioned as a selling point in the advertising brochure. Some renters have even placed a ☹️in their Trip Advisor review, disappointed that it never appeared during their stay.

Something, however, has jarred and jolted the spiritual ambience of the old stones out of kilter, and a far more sinister manifestation has claimed the cottage. There is a dramatic moment when, while Tony and his wife Charlie are making love in front of the log burning stove, with the children all sound asleep upstairs, a spectral hand grips Charlie’s throat. Far more chilling, however, is the moment when eight year-old Alfie appears at the foot of the stairs one night and says:

“Daddy, there’s a man in my room.“

Without giving too much away, the Mountfords’ stay at the cottage doesn’t end well, and after a few months the property is back on the market. Gavin and Simon are a fairly wealthy gay couple and they become the new owners. They decide to gut the interior of the building, stripping it right back to beams, brick and stone and – as far as the local council planners will allow – fully modernise it. In the process they make two startling discoveries. They find a deep well beneath the house, but of greater significance is that the builders have unearthed steps leading down to what can only be described as some kind of a cell. It has bars on the door, through which something of the inside can be seen, but the door remains resolutely locked. Robert Derry has a profound understanding of the latent power of old buildings, ghosts or not, and he describes it beautifully:

“After all, the heavy wooden beams were once living breathing things, until some mediaeval carpenters had cut them down in their prime. Then as seasoned joists they’d been hoisted up to hang from finely crafted oak A-frames, each chiselled peg dovetailed into carved sockets like ancient teeth in an angled jawbone. Dead men, whose hands had once lovingly laboured to shape each broad blade that would one day bear a ton or two of hand-hewn reads. The same dead men that now lay their heads further up the lane; a yew lined root that leads to a secluded graveyard which has long since laid its single tracked secrets to rest.”

As Gavin researches the history of what they pair had hoped would be their ‘forever home’, it is clear that in the mid seventeenth century the house witnessed truly evil acts, and that trauma seems to have been absorbed into the very bricks and mortar. Someone – or something – seems trapped, angry and in pain, and will not leave Gavin and Simon in peace until it is freed. This is an excellent account of dark deeds from the past intruding into modern lives, and Robert Derry has written a very convincing and plausible ghost story, with several moments that are genuinely disturbing. The Burning is independently published, and is available now.

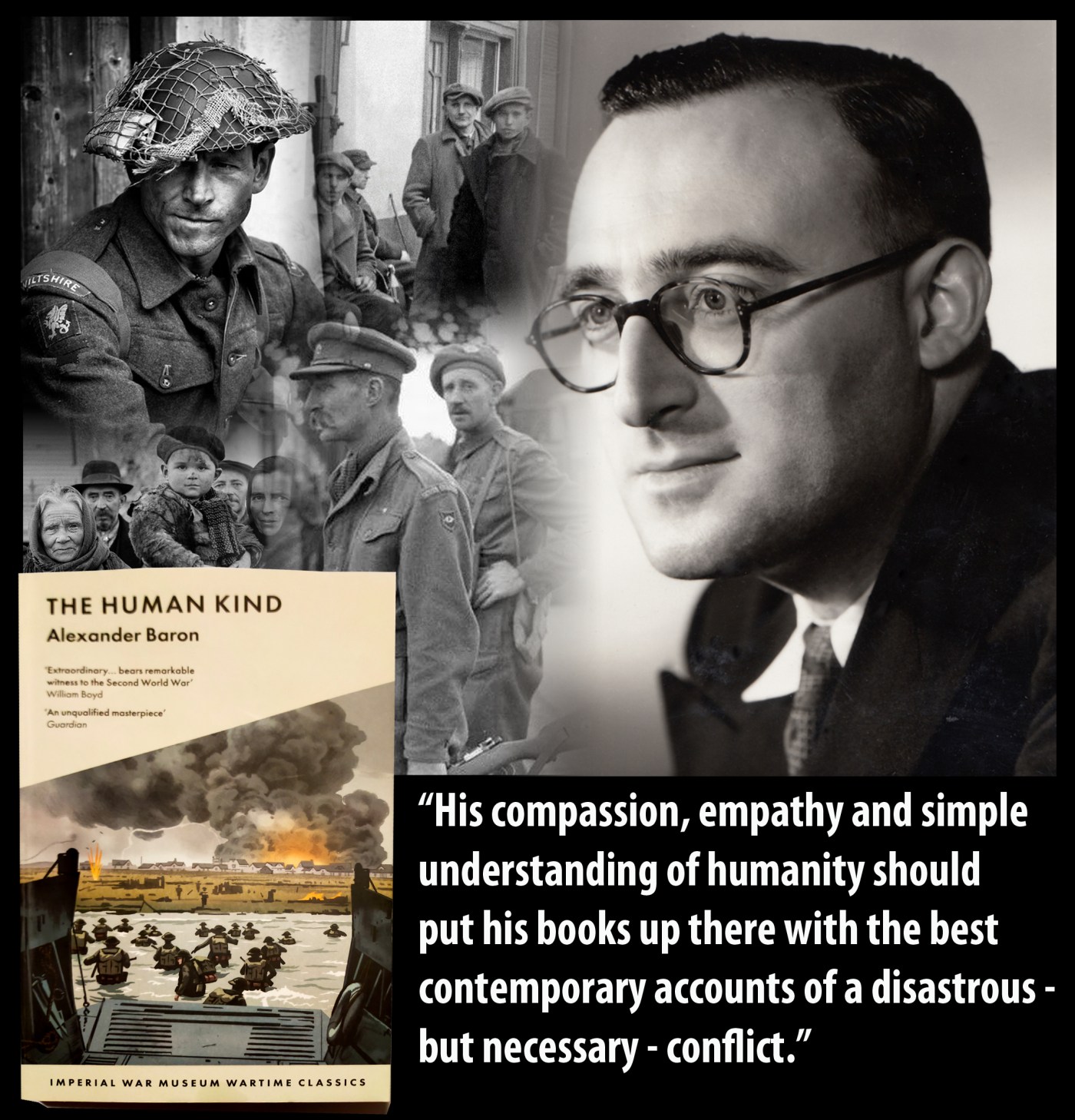

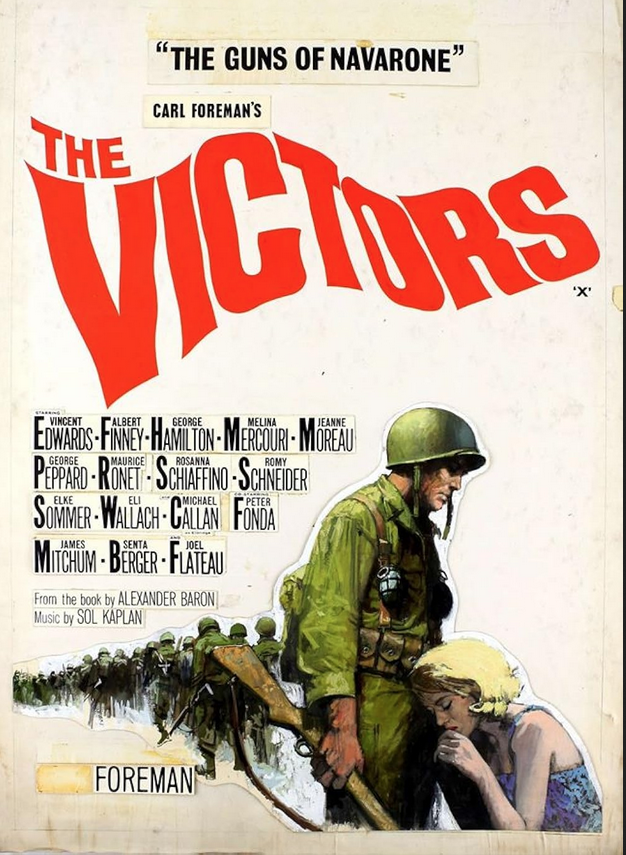

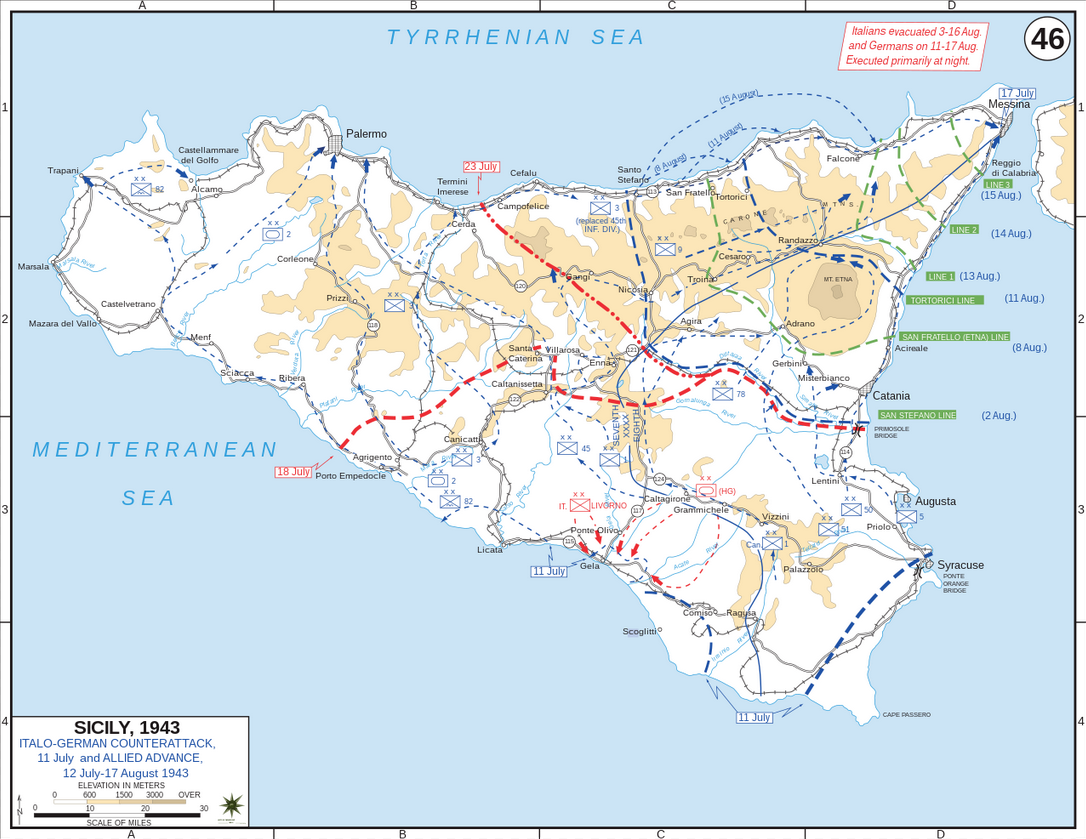

There is black humour in some of the stories, as well as a dark awareness of sexuality. In Chicolino, the soldiers in Baron’s platoon ‘adopt’ a homeless Sicilian boy, just into his teens. They share rations with him and treat him kindly, but are shocked to the core when he assumes that they will want to have sex with him in return for their kindness. He would have been quite happy to oblige, and is hurt and humiliated by their rejection. In The Indian, Baron retells the story from There’s No Home of how Sergeant Craddock comes to sleep with the beautiful Graziela. It is the appearance of a drunk but harmless Indian soldier that brings them into each other’s arms. Readers who, like me, are long in the tooth, will remember watching a 1963 movie called The Victors, directed by Carl Foreman. Alexander Baron was the screenwriter, and the story Everybody Loves a Dog, which relates the unfortunate consequences of a friendless and inarticulate Yorkshire soldier befriending a stray dog, was one of many memorable scenes in the film.

There is black humour in some of the stories, as well as a dark awareness of sexuality. In Chicolino, the soldiers in Baron’s platoon ‘adopt’ a homeless Sicilian boy, just into his teens. They share rations with him and treat him kindly, but are shocked to the core when he assumes that they will want to have sex with him in return for their kindness. He would have been quite happy to oblige, and is hurt and humiliated by their rejection. In The Indian, Baron retells the story from There’s No Home of how Sergeant Craddock comes to sleep with the beautiful Graziela. It is the appearance of a drunk but harmless Indian soldier that brings them into each other’s arms. Readers who, like me, are long in the tooth, will remember watching a 1963 movie called The Victors, directed by Carl Foreman. Alexander Baron was the screenwriter, and the story Everybody Loves a Dog, which relates the unfortunate consequences of a friendless and inarticulate Yorkshire soldier befriending a stray dog, was one of many memorable scenes in the film.

I have to confess that the crime fiction obsession with Scandi crime a decade ago came and went, as far as I was concerned. Some of it was very good, but to this old cynic it seemed that as long as an author had a few diacritic signs in their name, they were good for a publishing deal. Heresy, I know, but there we are. Back From The Dead is not a Scandi crime novel translated into English. The author (left) was born in Copenhagen, but has lived for many years in London, and she writes in English.

I have to confess that the crime fiction obsession with Scandi crime a decade ago came and went, as far as I was concerned. Some of it was very good, but to this old cynic it seemed that as long as an author had a few diacritic signs in their name, they were good for a publishing deal. Heresy, I know, but there we are. Back From The Dead is not a Scandi crime novel translated into English. The author (left) was born in Copenhagen, but has lived for many years in London, and she writes in English.