The distinguished Australian crime writer Peter Temple has died of cancer at the age of 71 at his home in the Victorian city of Ballarat. When some modern writers might have their output weighed rather than critically assessed, Temple wrote just nine novels and devoted much of his career to journalism – at which he excelled – and teaching others how to write. Nine novels only, but each is a gem – polished, hard, multi-faceted and brilliant. If he is known at all among casual readers of crime fiction in Britain, it may be for his four novels featuring the gritty private investigator, Jack Irish.

Irish, a former lawyer, inhabits an Australia which might surprise those who have never lived and worked in Melbourne. November through to March in the Victorian capital is pretty much the stereotype beloved of those who caricature Aussie life. It gets bloody hot, you don’t leave home without fly repellant and, across at the MCG, cricket fans, with the obligatory Eskies full of beer, are baying at the opposition players. But visit Melbourne between April and October, and you see a different city. The winter rain is usually an incessant but penetrative drizzle rather than a downpour and the wise supporter wraps up well to go and support his ‘footie’ team on a Saturday afternoon. The world of football – that strange hybrid we know as Aussie Rules – is one of the two contrapuntal themes in the Jack Irish novels, the other being the big business of horse racing. Whereas Jack Irish comes no closer to football than gloomy suburban pubs where old men rage against the dying of the light – and the current losing streak of their local team – his horse racing connections are far more potent. He has an uneasy relationship with a millionaire former jockey and the ruthless minder who looks after him, and his loyalty to the pair is sometimes repaid in cash but, on other occasions, with supportive but devastating violence.

The four Jack Irish novels are all in print, as follows:

Bad Debts (1996)

Black Tide (1999)

Dead Point (2000)

White Dog (2003)

Never content to rest comfortably in the arms of a literary formula, Temple also wrote five other novels, each with a different protagonist, as follows:

An Iron Rose – featuring Mac Faraday (1998)

Shooting Star – featuring Frank Calder (1999)

In The Evil Day – featuring John Anselm (2002)

The Broken Shore – featuring Joe Cashin (2005)

Truth – featuring Steven Villani (2009)

In The Evil Day is the only one of Temple’s works that has an international flavour. John Anselm is an ex-Beirut hostage who is eking out an existence working in surveillance in Hamburg, but becomes involved with a beautiful investigative journalist in London and an unscrupulous mercenary. Messrs Faraday, Calder and Cashin, on the other hand, ply their trade in deeply conservative country towns a couple of hours up the highway from the bright lights of Melbourne. Steven Villani, however, is back in Melbourne (which may seem more English than England, with its daily evensong at St Paul’s Cathedral, and its exclusive gentleman’s clubs) but there is nothing cosy or quaint about the corruption and venality that the hard-bitten police officer must confront.

Peter Temple was a fine journalist. Part of his training would have involved being cudgeled by hard-nosed editors into saying as much as possible in the fewest words. In his novels he added the imagination of a poet and the compassionate humility of a medieval saint. We have lost a writer who employed a style that was so terse and direct that it gave him the space and time for moments of such grace and perception that they take the breath away.

Six Strings is a quick thriller, an hour’s intrigue and entertainment. It features characters from the JJ Stoner / Killing Sisters series. You don’t need to have read any of the other stories in the series: you can start right here if you like.

Six Strings is a quick thriller, an hour’s intrigue and entertainment. It features characters from the JJ Stoner / Killing Sisters series. You don’t need to have read any of the other stories in the series: you can start right here if you like.

The rider wears a helmet – great head protection, that’s why the law compels them. He wears a face mask, great precaution against suicidal 100mph wasps, and a perfect disguise. He wears leather, and body armour tough enough to slow a small calibre handgun round to the point where it hurts, but is unlikely to be fatal. All of that in full view of anyone who might be looking.

The rider wears a helmet – great head protection, that’s why the law compels them. He wears a face mask, great precaution against suicidal 100mph wasps, and a perfect disguise. He wears leather, and body armour tough enough to slow a small calibre handgun round to the point where it hurts, but is unlikely to be fatal. All of that in full view of anyone who might be looking.

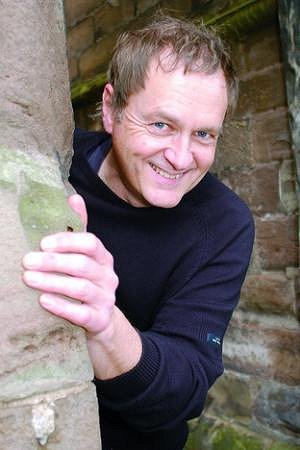

When it comes to creating a sense of place in their novels, there are two living British writers who tower above their contemporaries. Phil Rickman, (left) in his Merrily Watkins books, has recreated an English – Welsh borderland which is, by turn, magical, mysterious – and menacing. The past – usually the darker aspects of recent history – seeps like a pervasive damp from every beam of the region’s black and white cottages, and from every weathered stone of its derelict Methodist chapels. Jim Kelly’s world is different altogether. Kelly was born in what we used to call The Home Counties, north of London, and after studying in Sheffield and spending his working life between London and York, he settled in the Cambridgeshire cathedral city of Ely.

When it comes to creating a sense of place in their novels, there are two living British writers who tower above their contemporaries. Phil Rickman, (left) in his Merrily Watkins books, has recreated an English – Welsh borderland which is, by turn, magical, mysterious – and menacing. The past – usually the darker aspects of recent history – seeps like a pervasive damp from every beam of the region’s black and white cottages, and from every weathered stone of its derelict Methodist chapels. Jim Kelly’s world is different altogether. Kelly was born in what we used to call The Home Counties, north of London, and after studying in Sheffield and spending his working life between London and York, he settled in the Cambridgeshire cathedral city of Ely. It is there that we became acquainted with Philip Dryden, a newspaperman like his creator but someone who frequently finds murder on his doorstep (except he lives on a houseboat, which may not have doorsteps). While modern Ely has made the most of its wonderful architecture (and relative proximity to London) and is now a very chic place to live, visit, or work in, very little of the Dryden novels takes place in Ely itself. Instead, Kelly, has shone his torch on the bleak and vast former fens surrounding the city. Visitors will be well aware that much of Ely sits on a rare hill overlooking fenland in every direction. Those who like a metaphor might well say that, as well as in terms of height and space, Ely looks down on the fens in a haughty fashion, probably accompanying its haughty glance with a disdainful sniff. Kelly (above) is much more interested in the hard-scrabble fenland settlements, sometimes – literally – dust blown, and its reclusive, suspicious criminal types with hearts as black as the soil they used to work on. Dryden usually finds that the murder cases he becomes involved with are usually the result of old grievances gone bad, but as a resident in the area I can reassure you that in the fens, grudges and family feuds very rarely last more than ninety years

It is there that we became acquainted with Philip Dryden, a newspaperman like his creator but someone who frequently finds murder on his doorstep (except he lives on a houseboat, which may not have doorsteps). While modern Ely has made the most of its wonderful architecture (and relative proximity to London) and is now a very chic place to live, visit, or work in, very little of the Dryden novels takes place in Ely itself. Instead, Kelly, has shone his torch on the bleak and vast former fens surrounding the city. Visitors will be well aware that much of Ely sits on a rare hill overlooking fenland in every direction. Those who like a metaphor might well say that, as well as in terms of height and space, Ely looks down on the fens in a haughty fashion, probably accompanying its haughty glance with a disdainful sniff. Kelly (above) is much more interested in the hard-scrabble fenland settlements, sometimes – literally – dust blown, and its reclusive, suspicious criminal types with hearts as black as the soil they used to work on. Dryden usually finds that the murder cases he becomes involved with are usually the result of old grievances gone bad, but as a resident in the area I can reassure you that in the fens, grudges and family feuds very rarely last more than ninety years In the Peter Shaw novels, Kelly moved north. Very often in non-literal speech, going north can mean a move to darker, colder and less forgiving climates of both the spiritual and geographical kind, but the reverse is true here. Shaw is a police officer in King’s Lynn, but he lives up the coast near the resort town of Hunstanton. Either by accident or design, Kelly turns the Philip Dryden template on its head. King’s Lynn is a hard town, full of tough men, some of whom are descendants of the old fishing families. There is a smattering of gentility in the town centre, but the rough-as-boots housing estates that surround the town to the west and the south provide plenty of work for Shaw and his gruff sergeant George Valentine. By contrast, it is in the rural areas to the north-east of Lynn where Shaw’s patch includes expensive retirement homes, holiday-rental flint cottages, bird reserves for the twitchers to twitch in, and second homes bought by Londoners which have earned places like Brancaster the epithet “Chelsea-on-Sea.”

In the Peter Shaw novels, Kelly moved north. Very often in non-literal speech, going north can mean a move to darker, colder and less forgiving climates of both the spiritual and geographical kind, but the reverse is true here. Shaw is a police officer in King’s Lynn, but he lives up the coast near the resort town of Hunstanton. Either by accident or design, Kelly turns the Philip Dryden template on its head. King’s Lynn is a hard town, full of tough men, some of whom are descendants of the old fishing families. There is a smattering of gentility in the town centre, but the rough-as-boots housing estates that surround the town to the west and the south provide plenty of work for Shaw and his gruff sergeant George Valentine. By contrast, it is in the rural areas to the north-east of Lynn where Shaw’s patch includes expensive retirement homes, holiday-rental flint cottages, bird reserves for the twitchers to twitch in, and second homes bought by Londoners which have earned places like Brancaster the epithet “Chelsea-on-Sea.”

There are no honourable mentions here, because, (if you’ve been good) you will have seen them all in the previous four posts. Regular readers of this blog, and those who read my interviews, reviews and features on Crime Fiction Lover, will know that I am a massive fan of Phil Rickman’s books and, in particular, the series featuring the thoroughly modern, but often conflicted, parish priest, Merrily Watkins. She is one of the most intriguing and best written characters in modern fiction, but Rickman (left) doesn’t stop there. He has created a whole repertory company of supporting characters who range in style and substance from the wizened sage Gomer Parry – he of the roll-up fags and uncanny perception (often revealed as he digs holes for septic tanks) – to the twin-set and pearls imperturbability of the Bishop’s secretary, Sophie. In between we have the fragile genius of Merrily’s boyfriend, musician Lol Robinson, the maverick Scouse policeman Frannie Bliss and, of course, Merrily’s adventurous daughter Jane, for whom the soubriquet ‘Calamity” would fit nicely, such is her propensity to go where both angels – and her anxious mother – fear to tread.

There are no honourable mentions here, because, (if you’ve been good) you will have seen them all in the previous four posts. Regular readers of this blog, and those who read my interviews, reviews and features on Crime Fiction Lover, will know that I am a massive fan of Phil Rickman’s books and, in particular, the series featuring the thoroughly modern, but often conflicted, parish priest, Merrily Watkins. She is one of the most intriguing and best written characters in modern fiction, but Rickman (left) doesn’t stop there. He has created a whole repertory company of supporting characters who range in style and substance from the wizened sage Gomer Parry – he of the roll-up fags and uncanny perception (often revealed as he digs holes for septic tanks) – to the twin-set and pearls imperturbability of the Bishop’s secretary, Sophie. In between we have the fragile genius of Merrily’s boyfriend, musician Lol Robinson, the maverick Scouse policeman Frannie Bliss and, of course, Merrily’s adventurous daughter Jane, for whom the soubriquet ‘Calamity” would fit nicely, such is her propensity to go where both angels – and her anxious mother – fear to tread.

In All Of a Winter’s Night a young man has been killed in a mysterious car crash, and his funeral attracts bitterly opposed members of the same family. Merrily tries to preside over potential chaos, and her efforts to ensure that Aidan Lloyd rest in peace are not helped when his body is disinterred, dressed in his Morris Man costume, and then clumsily reburied. Rickman adds to the mix the very real and solid presence of the ancient church at Kilpeck, with its pagan – and downright vulgar (in some eyes) carvings. The climax of the novel comes when Merrily tries to conduct a service of remembrance in the tiny church. What happens next is, literally, breathtaking – and one of the most terrifying and disturbing chapters of any novel you will read this year or next. With its memorable mix of crime fiction, menacing landscape, human jealousy, sinister tradition and pure menace, All Of a Winter’s Night is my book of 2017.

In All Of a Winter’s Night a young man has been killed in a mysterious car crash, and his funeral attracts bitterly opposed members of the same family. Merrily tries to preside over potential chaos, and her efforts to ensure that Aidan Lloyd rest in peace are not helped when his body is disinterred, dressed in his Morris Man costume, and then clumsily reburied. Rickman adds to the mix the very real and solid presence of the ancient church at Kilpeck, with its pagan – and downright vulgar (in some eyes) carvings. The climax of the novel comes when Merrily tries to conduct a service of remembrance in the tiny church. What happens next is, literally, breathtaking – and one of the most terrifying and disturbing chapters of any novel you will read this year or next. With its memorable mix of crime fiction, menacing landscape, human jealousy, sinister tradition and pure menace, All Of a Winter’s Night is my book of 2017.

So, who thrilled me the most? First across the line by a nose, in a very competitive field, was

So, who thrilled me the most? First across the line by a nose, in a very competitive field, was

Every book I’ve mentioned won admirers from different sections of the reading public but, for me, the die was cast when a rather shy young man read the opening paragraphs of his soon-to-be-published novel at a book promotion evening in a smart Fitzrovia Hotel. Joseph Knox (left) may still have work to do to become a Richard Burton in the making, but

Every book I’ve mentioned won admirers from different sections of the reading public but, for me, the die was cast when a rather shy young man read the opening paragraphs of his soon-to-be-published novel at a book promotion evening in a smart Fitzrovia Hotel. Joseph Knox (left) may still have work to do to become a Richard Burton in the making, but